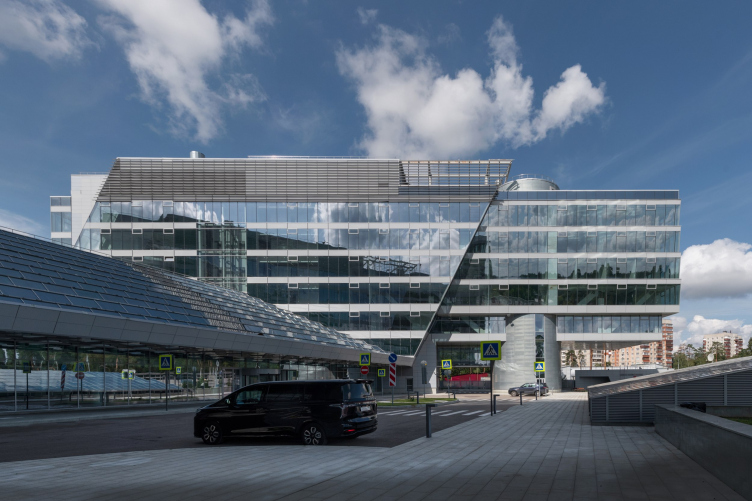

The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: Photo © Aleksey Naroditsky / provided by Reserve Union

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact reason for that – perhaps because of its location in the Moscow region or the lengthy construction process spanning six years, from 2011 to 2017. During that time, UAC’s management reconsidered using Zhukovsky for the headquarters, partly citing employees’ reluctance to commute from Moscow. The main office ultimately moved to Moscow’s Bolshaya Pionerskaya Street, in a space four times smaller. The Zhukovsky building, designed for 1,500 employees, now houses companies like Red Wings. Although completed in 2018, the site was only recently cleared, allowing for these new photos that we are about to show you.

Nonetheless, the building was designed and executed as a true headquarters, complete with all the technical features, a conference hall, a 25-meter pool, and a layout blending open spaces and executive offices – including an open terrace outside the president’s office with views of the airfield. The atrium is notably spacious and bright, with an unusual design that opens up from the entrance, almost blossoming as it reveals a three-story section framed by slender columns and intersecting stair flights.

In 2011, Reserve Union won the closed-door competition for the UAC headquarters.

The building concept came together very quickly since we were invited to the competition at the very last moment. We sketched the design almost overnight, submitted it, and won – apparently due to the resemblance of the building’s layout to a stealth-type aircraft.

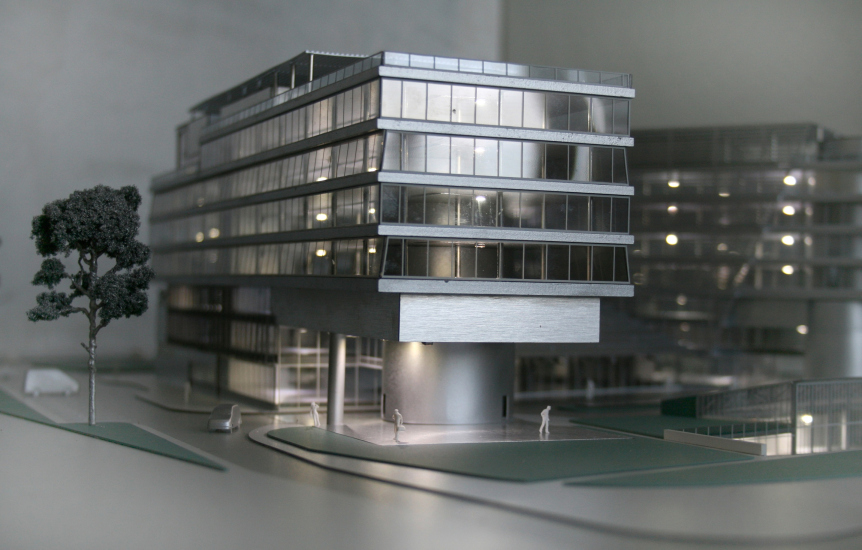

Later, the client insisted that the original idea be fully realized, including the triangular canopy that resembles the nose of a plane and the overhanging sections. To ensure their structural integrity, we added a framework construction within the cantilevered part.

Later, the client insisted that the original idea be fully realized, including the triangular canopy that resembles the nose of a plane and the overhanging sections. To ensure their structural integrity, we added a framework construction within the cantilevered part.

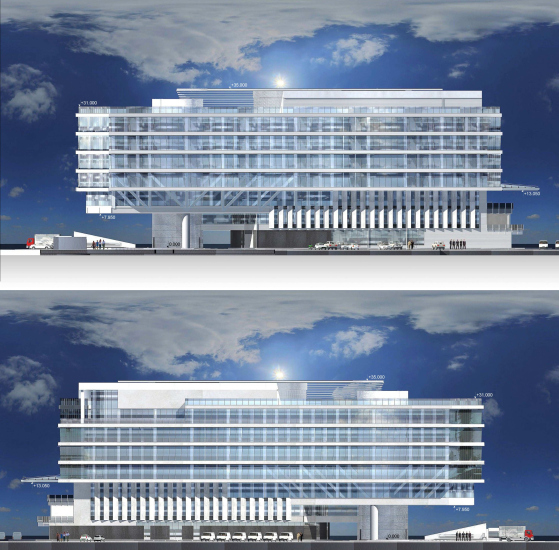

The building’s aerodynamic shape is also emblematic of its headquarters status – perhaps even essential. Here, it’s not just about the layout; the entire structure resembles something airborne, which is perfect for a conglomerate of aerospace companies.

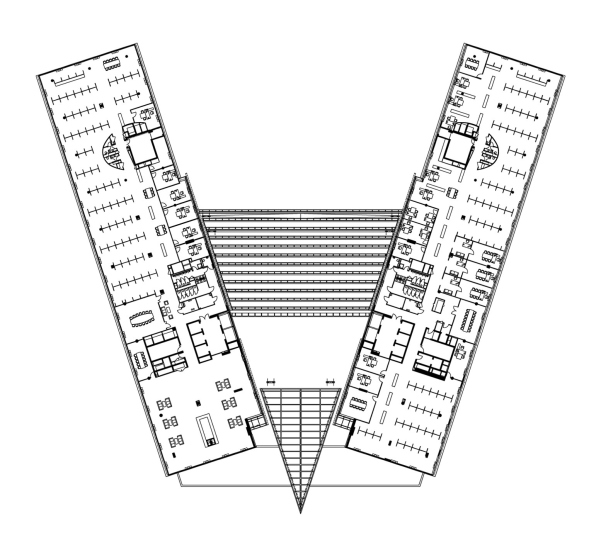

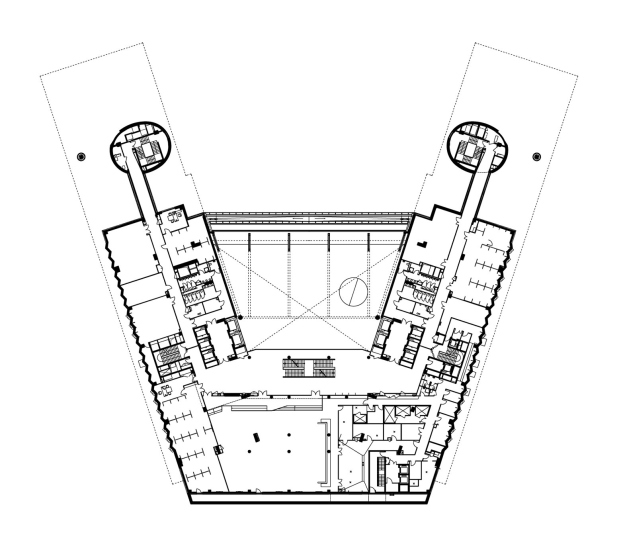

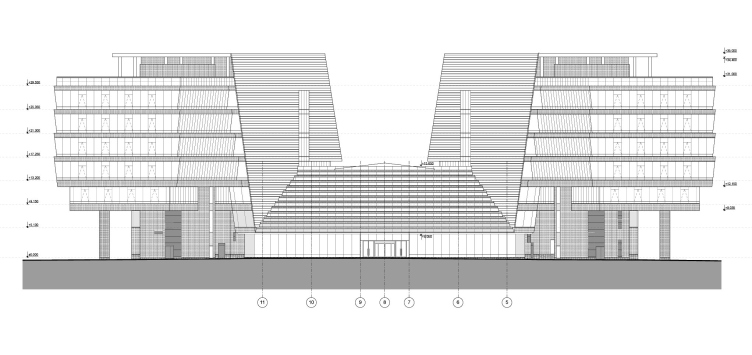

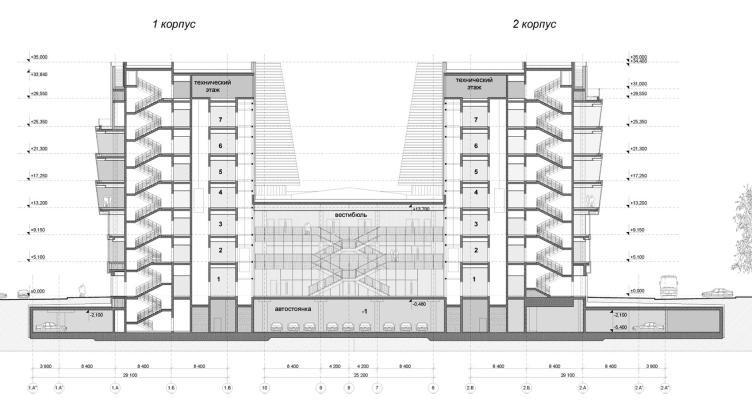

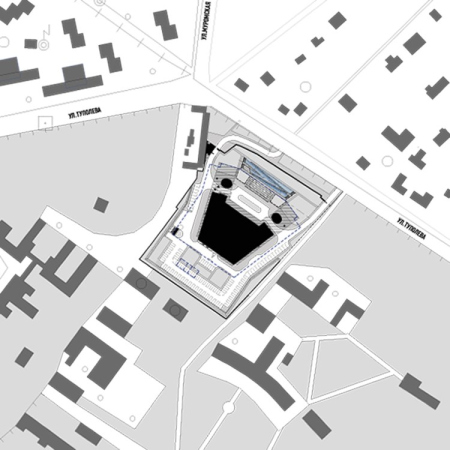

Yet, it’s not a plane-shaped building by any means. The level of abstraction is skillfully maintained, mostly through precise geometric lines. Two nearly identical elongated blocks, each 85 meters long and around 20 meters wide, fan out symmetrically along an axis perpendicular to Tupolev Street, the main thoroughfare. The angle of divergence is 36° – a tenth of a full circle. It’s intriguing to wonder if this angle holds any specific significance in aerospace engineering, as radar screen rays come to mind. While no concrete correlation was found, 36° is known to be the maximum dispersion angle for directional lights, such as flashlight beams.

The two rectangular blocks don’t converge directly; the rays formed by their inner facades meet beyond the structure, outlining the shape of a triangular canopy above a large balcony on the building’s southern end.

It’s a simple and elegant composition. Looking at the plan, you realize that these two lines, which so effortlessly organize the space, define the voids and the mass, the open areas and the filled spaces – surpassing even volume, form, and narrative in importance. It’s striking to see how everything rests on just a couple of lines, lending a surprising lightness to the foundation.

And yet, form is undeniably present: both fluid and impactful, communicating something meaningful to the observer. In fact, there are essentially two forms here. The first is the core and structure – the two blocks that make up the “body” of the building. About half of their length, around 40 meters, floats over the courtyard, supported by massive oval stair towers. These towers pierce the wings from the ground up, protruding visibly on the roof and on all sides of the courtyard, integrating into the structure. These substantial “communication tubes” were part of the project from the outset, as evidenced in the early 2011 model.

The towers function as through-pillars, solid anchors. Unlike the conceptual axial geometry of the plan, their rounded, fluid forms add a sense of stability, resilience, and grounding. Acting as bracing elements, they enable cantilevers extending 15 meters forward and 13-meter wide passageways beneath. On the exterior contour, each tower is reinforced by a single circular column – its diameter slightly larger than that of the regular structural columns. On the blueprint, the towers resemble eyes, with the column dots reminiscent of trendy tattoos.

So! The space beneath half of each block is open to both view and movement: the volumes are elevated on “legs” – a classic and beloved technique of 20th-century architecture pioneered by figures like Le Corbusier and Ginzburg. The first level remains free, while the second connects the stair towers to the blocks via a suspended glass walkway, providing convenient alternative entry points. This passage “clings” to the third floor, which, like the levels below, is narrower and shorter than the floors above. Here, the mass of the lower tiers builds gradually upward.

The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: Photo © Aleksey Naroditsky / provided by Reserve Union

This theme develops across the longitudinal façades of the middle section, from the fourth to the seventh floors. These floors expand diagonally, widening from bottom to top and forming, when viewed in cross-section, a silhouette reminiscent of an upside-down, stylized Christmas tree. We can observe this “cutout” effect at the ends of the blocks.

This solution is uncommon and still rarely seen. A similar form can be found in the design of the clinic building in Kommunarka, also by Reserve Union

The slanted surfaces fracture the reflections, adding stripes, brightening, and energizing the resulting deep shadows.

These planes also transform what might have been an inert façade of ribbon windows into a kind of “plastique attraction”. The inclined surfaces create a sense of intrigue, enhanced by the rhythm of vent windows articulated by light-colored frames. Originally, the opening window sashes were meant to occupy most of the vertical part of the window, allowing the glass to shift from a slant to vertical when opened. However, the architects ultimately opted for smaller vent windows at the top. On the façades, they too resemble a multitude of eyes, quietly observing.

On closer inspection, the 9° tilt angle of the bands from the 4th to the 7th floors matches – or nearly matches – the tilt of the inner “shell” walls facing the courtyard. This angle, 9°, represents precisely one-fourth of the primary 36° angle that defines the plan’s geometry.

Facade,, view from the north. The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: © Reserve Union

These “inner shells” deserve special mention – they comprise the second key aspect of the building’s design.

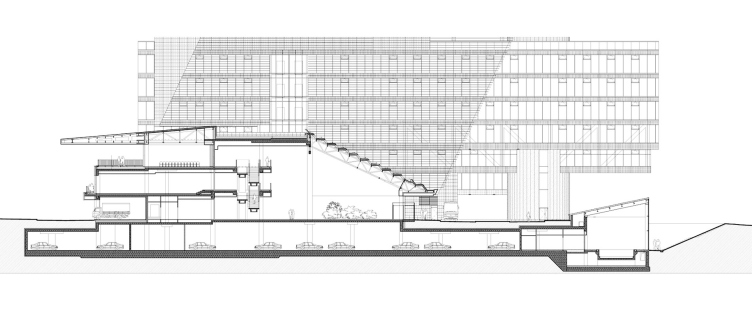

While the primary structure forms the core, this secondary layer acts more like an outer “shell” or “cloak” draped over the building’s volumes. One might say that the first form is functional, while the second supplies the narrative. This “second form” enhances the theme of flight, evoking wings, uplift, and maintaining associations with an airplane or a bird. This layer is not merely draped but also integrated, with components like diagonal projections of glass walls shielded by louvers, pergola grills on the roof, an overhang “beak”, and the atrium’s roof – its “tail.”

This continuous “nose-to-tail” profile is clear from above and in sectional views, where the canopy structure extends the atrium roofline, while the “wings” sweep upward along the façade.

Longitudinal section. The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: © Reserve Union

The whole figure is distinguished, first, by a striped texture – louvers, slats, and folded roofing – and second, by a series of planes resembling origami. Together, these elements recall either a spacecraft with upturned wings (reminiscent of designs familiar to everyone from “Star Wars”) or a paper crane seemingly alighting on the headquarters of an aerospace company. This is more than appropriate in this case: inside the building, airplanes are designed, while outside, a symbolic aircraft appears to take shape from structural forms – a visual representation of engineering ideas. This “flight” theme was embedded in the original design concept, with the building’s inner contours embracing the beams of the blocks, which then project out from the shell.

By 2022, most of the side façade and pergola louvers were in place, enhancing the “avian” silhouette, emphasizing the layering of forms, and creating reflections from the roof that conjure additional ghostly wings in perspective.

Currently, the louvers on the inner side façades have been removed, but we can hope they’ll be reinstalled, restoring the unified “wing” silhouette.

Even so, the sharp diagonal cutting across the façade already conveys a “flying” profile. When viewed from a courtyard angle through the open space beneath one wing towards the other, the building reveals a striking origami effect, as though assembled from intersecting planes – like a structure made from folded paper, or glass and metal. Geometry plays a critical role in this impression; the angle between the atrium roof’s slope and the diagonal projection on the façade is exactly 90°. This precision allows the interrelation of lines and angles to be fully felt, reinforcing the building’s design logic where each angle connects harmoniously to the next and one thing leads to another.

The tilt of the atrium roof, reminiscent of a spacecraft gangway, suggests a sense of purposeful mechanics.

And where there’s mechanics, there’s also dynamics. This internal “drive” is tangible, regardless of how the louvered textures layer upon it.

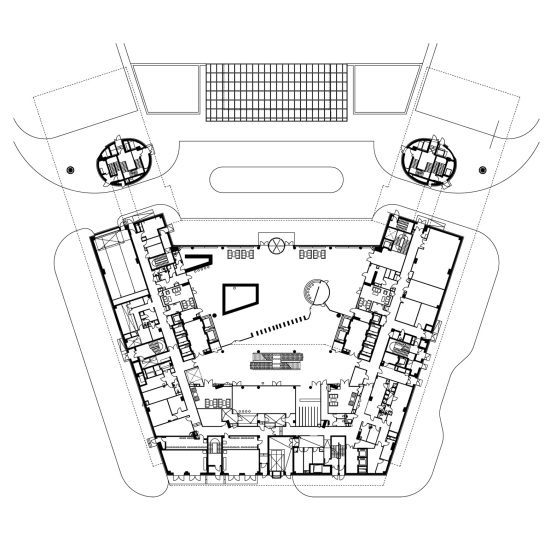

In the southern section, where there are no cantilevered sections, the facades of the three lower “podium” floors are designed like an accordion of triangular bays. Half of each triangle is solid, while the other half is glass, a signature approach of Vladimir Plotkin’s, seen previously in projects like Skolkovo Park and the distinctive serrated base of the “Faces” residential complex.

Here, the glass facets face south, capturing both sunlight and views of the forest.

View from the southern wing towards the northern one. The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: Photo © Aleksey Naroditsky / provided by Reserve Union

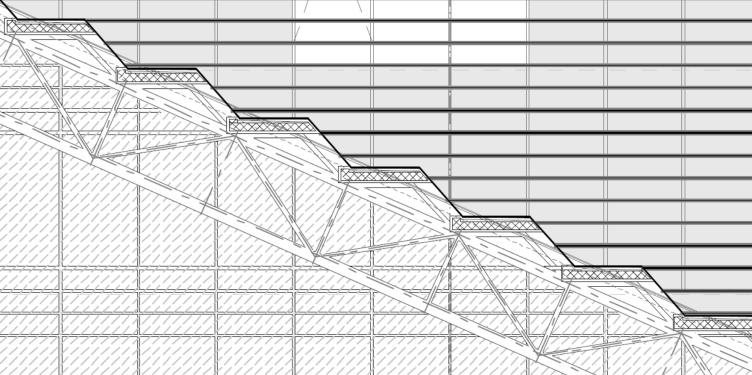

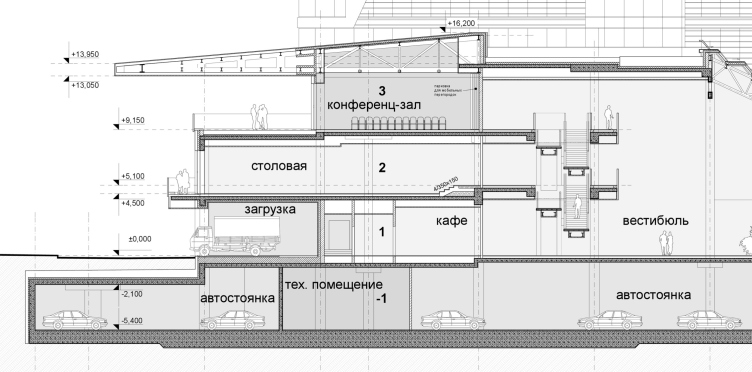

The stepped atrium roof complements this “accordion” or “bellows” design, with horizontal opaque surfaces interlaced with inclined glass sections set at 49°, each one heated to maintain clarity.

If all the surfaces were glass, horizontal panes would need frequent cleaning. However, with so many inclined glass sections, water naturally flows down them year-round, maintaining a clear view.

The principle of the roof is thus similar to that of sawtooth skylights, but smaller in scale. Despite the fact that the atrium opens to the northeast, the glass strips capture enough light, and the white structures inside effectively diffuse it. It’s debatable whether embossed airplane shapes on the end walls add value, but the white boomerang-shaped fixtures attached to the ceiling definitely fit perfectly within the space.

The roof of the atrium, a section view. Fragment. The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: © Reserve Union

The most intriguing feature of the atrium is its visual openness. Through the glass façade, it connects seamlessly with the street, while the internal balconies, sliced by a single plane, further strengthen the sense of unfolding space. This openness also reveals the full interior of the stylobate section in a singular cross-section view.

The grand staircase is especially noteworthy. On the one hand, it is suspended in the air and is cutting diagonally across the center, on the other – it appears in profile, as though cross-sectioned. Traditionally, a grand staircase in a multi-story lobby would wrap around the space in a Baroque manner. Here, however, the direct slice approach adds a different kind of intrigue, bringing the design drawing to life. This unconventional staging is compelling in its own right, as opposed to the hypothetical “classical” solution.

Here, in the southern trapezoidal area from the first to the third floors, there are cafés, a dining hall, and a conference room with large meeting rooms on either side. These spaces open not only into the atrium via internal balconies and the staircase but also to the outside. The southern façade features a dining hall balcony and a spacious eight-meter-deep terrace adjoining the conference hall, situated under the iconic canopy where the two main plan axes converge.

Cross-section view (3-3). The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: © Reserve Union

Other open terraces enhance the building’s adaptability. Aside from the balcony attached to the main office, both the flat atrium roof between the wings and the wings’ own roofs could potentially be used as outdoor spaces.

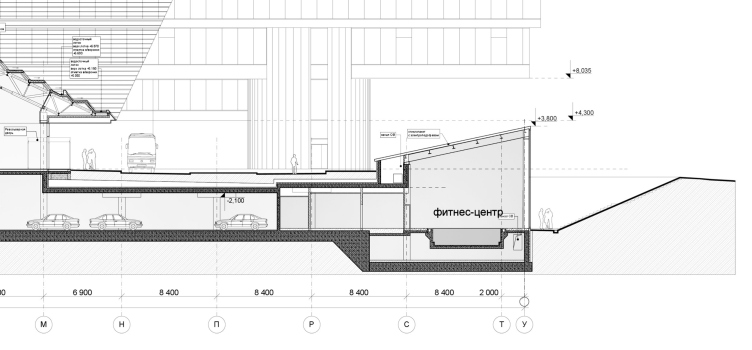

But there is more to it than that: the United Aircraft Corporation headquarters includes a fitness center for 78 people, featuring a 25x6 meter pool positioned near Tupolev Street and partially sunken into the ground. The locker rooms and workout areas are located at the underground parking level, while the pool itself is topped with a glass roof tilted southward to capture more natural light, with electrically heated glass, similar to the atrium. The fitness center’s northern façade, also entirely glass, overlooks a ramp and stair-accompanied slope.

Longitudinal section. Fragment. The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: © Reserve Union

This way, the pool area of the United Aircraft Corporation headquarters receives plenty of natural light, maybe even too much. In the courtyard, one can see an intriguing “meeting” of two inclined surfaces: one, the atrium’s tiered, striped roof, and the other, the roof over the pool.

Longitudinal section. Fragment. The building of the fitness center. The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: © Reserve Union

In the photographs, the fitness center’s raised section, tucked between two wings, can be seen from the “façade” side, almost like a “master key” controlling the building’s majestic movement.

The UAC headquarters building in Zhukovsky

Copyright: Photo © Aleksey Naroditsky / provided by Reserve Union

Designed almost entirely by the end of 2011, the United Aircraft Corporation building logically aligns with Vladimir Plotkin’s broader portfolio. Its parallels with the Aeroflot headquarters (2004–2010) reflect their shared aviation theme and headquarters status, yet the two buildings are by no means identical. Both feature “wings,” a composition of two structures with an atrium, courtyard, and reflections, along with stair towers beneath the wings. However, Aeroflot’s “catamaran” composition, rooted in Plotkin’s earlier work on the house at Zagorsky Passage (1998-1999), diverges significantly from the United Aircraft Corporation HQ. That being said, the differences begin, and these distinctions, though within the same paradigm, are sufficient to set them apart. The Huaming Park (2012–2023) shares a similar triangular layout and lamellae grid – like a “veil” that enhances the façade’s integrity. In addition other visual parallels gradually emerge, including those with Vladimir Plotkin’s outpatient hospital building in Kommunarka.

Yet all these elements converge into a new and highly individual character. This building stands out with a greater sense of “foldedness,” a play with planes and angles, and, once you find yourself within the company’s secure grounds, some sort of unexpected openness, a sense of the entire structure “unfolding.” The building even displays a layered or “stratified” quality in its glass-and-metal volumes. For example, where Aeroflot’s office had sharp, slanted noses, here both ends are cut by a flat plane, making them appear as segments of something larger – a kind of infinite ribbon. The concept of flight here is felt differently too, as if suggesting a gentle, perhaps gravity-defying landing. And we all know, after all, don’t we, that for airplanes those moments of takeoff and landing are the most crucial.