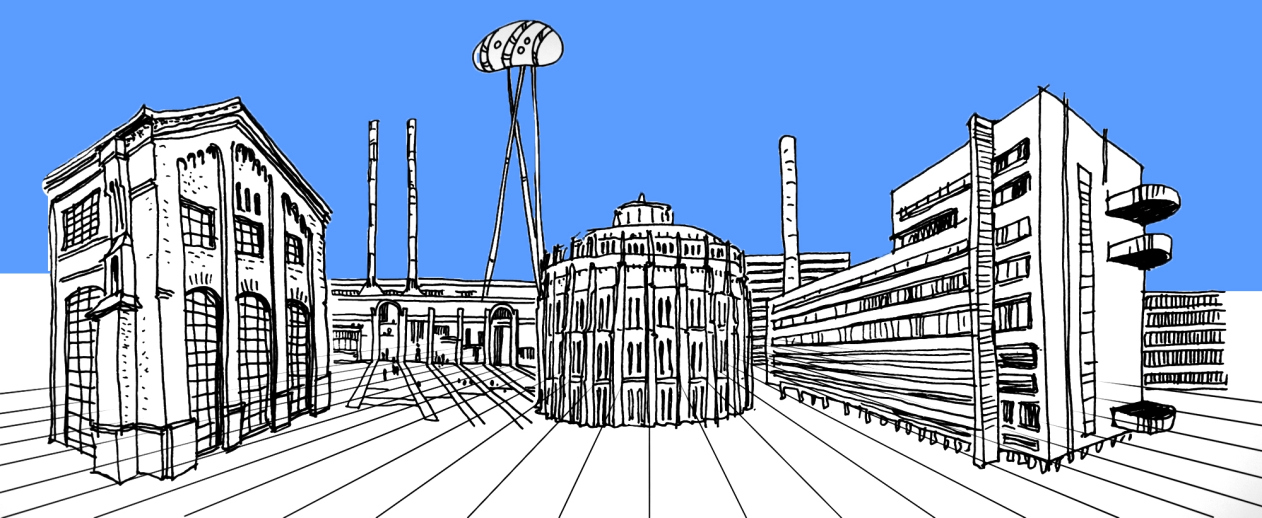

Pavel Andreev, Gran

“The steady public interest for reconstruction is a natural thing. Initially, the owners of what you may call “postindustrial property” tried to clear it from what construction machinery still remained there, and then they wanted to rent these premises out, which was much more profitable than trying to revive the production cycle. But today they’ve begun to wonder what else they can do to increase their return on investment. Besides, the number of land sites on which you can build in Moscow is shrinking rapidly, and the few ones that are left will be seized by the giants of the development sector. In these conditions, the industrial parks that are situated not far away from the city center naturally turn into potential construction sites. I don’t see any particular “surge” in the popularity of reconstruction as such, but the steady tendency is there. The owners of the industrial parks are reconstructing the active factories or move them outside the city boundaries, bringing the remaining part of the industrial park in order, and then turn all these buildings mostly into housing complexes (because housing stock sells better), and projects that serve public functions as well. So, if we are to speak about whether reconstruction is relevant or not, in short, my answer is “yes”.

***

Eugene Asse, Asse Architects, the president of MARCH architectural school

“If there is anything to speak about, it is the clearance of a great number of top-grade industrial parks that has been going on during recent years due to the near offshoring. Not all of the things that are going on here meet the definition of “reconstruction”, much less scientific restoration, which is, of course, a deplorable fact. What I’m saying is that a lot of territories are simply cleared up to accommodate for new construction, like, for example, the territory of the “Serp i Molot” factory. “ZIL” is also not so much about reconstruction as it is about developing the territory. And such examples are numerous. If we are to take the “Flakon” factory, for example, we will see that no reconstruction work was actually done – what they did in fact was some paint job. This is not “reconstruction”, this is a makeover. And as for serious reconstruction projects, they are few and far between. What Mikhelson and Renzo Piano are doing with GES-2 [in collaboration with APEX – editorial note] is a serious exemplary project.

The V-A-C foundation Center of Modern Culture in the former GES-2 power plant. Photo courtesy by Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW)

Copyright: Provided by Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW)

The V-A-C foundation Center of Modern Culture in the former GES-2 power plant. Photo courtesy by Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW)

The Museum of Russian Impressionism on the “Bolshevik” factory or the Institute of Russian Realist Art – these projects could also be considered as reconstruction. They maintain the main architectural merits of those days, and the buildings were brought into a decent state. One must be aware of the fact that most of the clients regard reconstruction as an expensive thing to do, and, to some degree, a waste of money and resources. When it comes to cultural heritage institutions, like the aforementioned museums, this means that business must be interested in creating a high-quality environment which presupposes careful treatment of your historical heritage.

The Museum of Russian Impressionism by John McAslan+Partners. Source: rusimp.su

The Museum of Russian Impressionism by John McAslan+Partners. Source: rusimp.su

In other cases, it’s easier for the client to tear everything down and build something new on that spot. Our project, Nizhny Novgorod’s “Arsenal” is precisely the case of the client’s and Nizhny Novgorod Center of Contemporary Art’s respectful attitude towards the reconstruction process, and I am very grateful to them for that.

The State Center of Contemporry Art in Nizhny Novgorod. The space of the central risalit. The second stage of construction, 2015. Photograph © Vladislav Efimov

The State Center of Contemporry Art in Nizhny Novgorod. The expanded exhibition space of the first floor. The second stage of construction, 2015. Photograph © Vladislav Efimov

I think, however, that the trend for careful treatment of your cultural heritage is not that wide-spread among the developers. True, the buildings of the XIX century are treated fairly well. But as far as the monuments of constructivist architecture of the ХХ century (in Ekaterinburg, for example) are concerned, they are treated really badly. What happened to the former “Pravda” factory is some sort of distortion of history. In order to justify the use of ceramic tiles, they even announced a competition for the façade material – only to mutilate the beautiful building with a modern atrocity. Probably, the “Izvestia” building is a fine example of respectful treatment of the architectural legacy of the ХХ century.

Restoration of the Izvestia Building, 2016 © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

So, I don’t see out there any particular “trend” for reconstruction. True, some architects may have a desire to embark on reconstruction projects but the client most of the time views it as an encumbrance”.

***

Mikhail Beilin, Citizenstudio

“Moscow has everything to develop intensively, not only extensively. Industrial parks and industrial facilities in general, the derelict land belonging to the so-called “rusty belt” have a huge potential in them. You don’t have to annex anything or change the border lines. This clearly makes reconstruction ever so relevant. And, most importantly, we must be aware of the fact that the unwelcome alternative to reconstruction is tearing buildings down altogether. And this means ending up getting a faceless city that forgot its roots. What we need to do is keep the identity of our city but fill it with a new meaning and make new history. I think that the demand for the identity of our city will grow with time. This would be natural for the development of society and the urban individual. To me, the opportunity to come up with this “new life”, by restoring and recreating, is the most interesting task. Taking part in creating or recreating things is something akin to magic. And, most importantly, this is working with the dramatic composition and the history of this city; it feels great to be a part of it”.

***

Aleksey Ginsburg, Ginsburg Architects

“The trend for radical changes was something that was big in the last century because many cities were destroyed in the Second World War and required new construction. Plus, in the first half of the XX century – against the background of the industrial revolution – there was still a strong trend for creating “prefab” cities. This trend gave way to a more local one, characteristic for historical cities which require reconstruction and restoration rather than new construction. In Russia, these changes only happened in the recent years. This has to do with the fact that society is beginning to realize the value of the material culture.

Project of restoration and adaptation of the cultural heritage site "Narkomfin Building" (2015-2017) © Ginsburg Architects

While 15 or 20 years ago people would prefer to build a new building (which seemed to be an easier thing to do), now we have this influential movement of city preservation activists – because society understands just how valuable our architectural legacy is. And I am not just speaking about the acclaimed architectural monuments – I am speaking also about decent old buildings with a history; their value, including the commercial aspect of it, is becoming ever more prominent. If we are to speak about the city fabric, what is important is not just preserving some “pinpoint” cultural heritage sites, but also simple rank-and-file buildings. This architectural baggage of the historical city is not at all that shabby after all. If we do away with it, we will get a plague of ugly new buildings.

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Reconstruction is a natural process that, instead of destroying the city environment, enriches it with restoration of unique buildings, adapting the historical environment to the new needs of society. And it is always better to act very tactfully here, treating each project as a unique case. The investors are beginning to realize that an old house or part of an old house can be valuable and increase the capitalization of the project. In our Trekhgorny Val project, for example, we reconstructed a building that got a buildup during the soviet times. In this building, we kept intact the most interesting walls that it had. There was yet another restoration project that we did on the Gilyarovskogo Street; our client had an official permission to tear down the old building but we talked him out of it. Of course, it would be a great thing if we put all the old buildings on the protected list but while this is not the case, it’s OK to act the way we do”.

***

Yuri Grigoryan, Meganom

“There is one big problem with reconstruction: nobody wants to bother themselves with such projects. Everybody wants to tear down an old building, at most – leave the old façade intact, or, better yet, blow up the whole thing altogether and build a new imitation in its place. This is basically what private developers think of reconstruction. They have two modes of action. The first (let’s call it a “vegetarian” mode) consists in just going ahead and using the old building as it is. For example, you take “ArtPlay” or the “Red October” factory, rent the place out, and let the tenants do their thing, as long as it doesn’t conflict with the federal legislation for protecting monuments of architecture. The second (and the most often used) mode is to level the site down to the ground and build something new upon it. So, reconstruction is an interesting genre that we just don’t have around here. Reconstruction is essentially about preserving most of the old building, and it is considered to be a more expensive thing to do than building from scratch, although no one can seriously prove it because our experience in this area is virtually nonexistent. Restoration, yes, it is an expensive thing to do indeed, but this is the way it is meant to be because you are dealing with a monument of architecture. And reconstruction (we have to distinguish between the two) is when an old building (mind, not a monument!) turns into an actively functioning project. For example, currently Rem Koolhaas is doing this project of Tretyakovskaya Gallery on the Krymsky Val – this is the classic reconstruction. Other examples of reconstruction are his “Garage” museum in the Gorky Park or London’s Tate Gallery by Herzog and de Meuron.

Tate Modern Gallery. Photo: Hans Peter Schaefer via Wikimedia Commons. GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2

Tate Modern Gallery. The Turbine Hall Photo: Hans Peter Schaefer via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0 License

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Model. © OMA

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Model. © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

They kept what was there, and they added new things. This is prestigious and expensive, and this is something that here only the wealthy connoisseurs of culture can afford – or such projects could be federally financed, for that matter, and then only on few select occasions. This is why there can be no “surge” by definition. If there is a “surge”, it is a surge of demolishing good and important old buildings. The “Krasny Bogatyr” factory is waiting to be torn down and replaced by housing projects, and it’s a very long list. If we are to take, for example, the fire substation and the avant-garde façades on the ZIL territory, developers also ultimately decided not to keep them – the costs were high, and the city people showed no interest in their preservation. So, from the cultural and professional standpoint, pretty much everything is wrong with reconstruction – the architectural monuments are few and far between, and what little is left is facing the prospect of demolition. And, as practice shows, the architecture of the new buildings is almost always worse than what was there before them”.

***

Daniel Lorentz, Natalia Sidorova, Konstantin Khodnev, DNK ag

“Today, redeveloping the former industrial territories is indeed relevant, especially here in Moscow. Today, on these territories, the production of industrial product gave way to the “production of square meters” of housing construction which draws a lot of profit.

A significant part of the industrial parks lies within the boundaries of the “old Moscow”, in the areas with a highly developed infrastructure, and because of that such land sites, with the overall deficit of land that is vacant for the construction, enjoy particular popularity among the developers. Reconstructing and readjusting the historical buildings of the industrial architecture constitute the historical fabric of this city, which is rather thin here, and this is why such work is very important and relevant.

The launch of the Moscow Ring Railway and the upgrade of the transport infrastructure increased the value of the former industrial park of Moscow’s “middle belt”, where they are predominantly situated”.

***

Valery Lukomsky, CityArch

“In my view, reconstruction, and generally, working with historical buildings, is one of the most exciting tasks for an architect. This is like top class performance – to come to grips with the building that was built in a different epoch and breathe a new life into it.

As far as popularity of reconstruction is concerned – I think this trend will continue. This growing urbanization makes all the cities look alike, leveling off their distinctive features. And it is very important to preserve the buildings that define the spirit and the uniqueness of their location. Such unique places attract tourists but they must also be made comfortable for their residents; and whatever valuable there is must be preserved too.

One of our recent projects – commissioned by the Ministry of Culture of Byelorussia – was developing the master plan of the historical center of Vitebsk, the so-called “Shagal Quarter”. We had to neutralize the destructive influence of the Soviet highway, reveal the morphology of the territory, and evict and highlight the monuments following the plan developed by the Scientific-Research and Design Institute of the General Plan of Moscow. You could call this a reconstruction of a whole city – on the post-Soviet land, there are plenty of cities that are in need of such work.

As far as direct reconstruction projects are concerned, we did such a project in 2009-2011, when we worked on the first stage of the Danilovskaya Manufactura. At that moment we were really lucky to work with our client, KR Properties. We saved everything that was worth saving, and what was it possible to save; repaired and conserved the brickwork. Unfortunately, it did not work out with the second stage of construction: our counterpart team from the side of the developer changed, and ultimately our concept was handed over to a Turkish construction company – and ultimately new buildings prevailed.

Reconstruction is a challenging and expensive thing to do. What matters here is the client’s interest in it – simply because tearing down the old building and then building something new on that site is usually easier and less expensive. However, you have to keep in mind that not on every site reconstruction makes sense: there are such messy pileups out there, where you could not save anything even if you wanted to – in this case what you need to do is rather try and convey the genius loci in your new project through visual and volumetric hints”.

***

Nikolai Pereslegin, Kleinewelt Architecten

“Reconstruction can be viewed as a whole bunch of processes of prolonging the life of old and not-so-old buildings because a lot of buildings that were built in the XX century and, yes, even in the beginning of the XXI century, are not always made up to standards – both in terms of the overall construction culture and from the aesthetic standpoint. For a rare exception, most of these new buildings can hardly be perceived as anything but temporary structures built on very expensive land. In this connection, I would treat the notion of “reconstruction” a little bit wider: the western sources distinguish up to ten different “re”, and they all are different in their approaches, methods, and volumes of the work performed. For instance, the western practice distinguishes between the notions of “rehabilitation” and “adaptation”. In this country, it is all covered by the “reconstruction” term. And if we are to perceive reconstruction in this specific context, we still have a lot of work to do – it’s enough to take a quick look around to understand that. And now we are only in the beginning of this path, there is work for generations to come: fixing the world is always more difficult than creating it from scratch. Today we see the world economy changing its trends, and, as a consequence, priorities shift on a micro level. From global mega projects, the vector is shifting towards the local increase of quality of what was created before us; hence the landscaping of the city territories or more careful treatment of your house entrance or your yard, which is only possible if we become responsible citizens. What is commonly known as reconstruction – I think that fully in this trend we can say that there is a relevant interest to this topic”.

***

Sergey Trukhanov, T+T Architects

“Of course, I am hoping that there will be a surge of interest for reconstruction, especially in Moscow. And, in my view, this will have to do not so much with new legal acts as with as with the large-scale development of the territories of this city on which new houses will be built upon the renovation program. One way or another, these large-scale interventions into the city environment will affect the existing urban context, which will be inevitably followed by the necessity for reconstructing the buildings that stand directly on this territory or are located close to it. These buildings can be not only valuable from the architectural or historical standpoint but also be important for these territories in terms of function or infrastructure. These can be community centers, museums, retail stores, business centers, and projects situated on the former industrial territories that adjacent to the renovation zones. Everything may become interesting for reconstruction in view of the increasing of the attractiveness of this area for new construction. For the same reason, reconstruction projects can also include derelict buildings, which, thanks to their architecture or mere location can form the living environment in their area. For them, what is going to be most important is the search for the right function for relaunching the building”.

***

Oleg Shapiro, Wowhaus

“In the conditions of developing any historical city, reconstruction is a usual, expensive but necessary thing to do; something that’s expected. It was, is, and will be there. But reconstruction projects will only become successful and profitable when the developers start believing in it, not just architects. A great example, which is now becoming a trend, is the heightened interest to preserving the so-called “production territories”: of the late XIX early XX centuries that appeared in Moscow 8-10 years ago, starting from Vinzavod, and which is still relevant today”.

***