The discussions of 2020 resulted in the project by Julius Borisov and the UNK architects taking center stage; it had secured second place in the competition. The project, created in partnership with Storaket (who worked on the spatial and planning solutions) and Mark Sattran’s “Smart School” (who proposed the educational space “technology”), was already in 2020 being compared to Apple’s headquarters for its tech-driven architecture and streamlined, cohesive form.

It received the “architectural and urban planning approval”, was listed among the nominees for the Moscow Mayor’s Architectural Award, and has now been realized faster than initially planned, as the construction timeline was shortened. However, the building closely resembles its original, conceptual version. It’s clear that both the building’s form and façades, from concept to realization, received significant attention from the architects.

The school in Garden Quarters

Copyright: Photograph: provided by UNK

The architects insisted, as the project’s author Julius Borisov shared, on implementing costly solutions: structural glazing, ceramics, and other expensive elements.

All our landmark projects are realized through competitions, either open-call or closed-door ones. We practically don’t have a single iconic project that was commissioned to us directly. We are constantly, so to speak, participating in “cutthroat competitions”. This particular competition posed a very complex task. The school was meant to become the culmination of an outstanding project – the Garden Quarters complex, where Sergey Skuratov and many other renowned architects worked. It’s a remarkable project with its own character, design code, and both strengths and weaknesses… Accordingly, this was a challenge. The second challenge was that I myself am a local resident, and I’m now considering the possibility that my fourth child will attend this particular school. So, I felt doubly responsible.

Thirdly, the site was not 100% suitable for a school building. It’s constrained in terms of sunlight exposure, with very difficult conditions and no space to place a proper sports core. Finally, the school building was meant to serve as the final highlight of the Garden Quarters, a sort of “cherry on top”. On the one hand, it had to adhere to the design code, but on the other, it had to contribute something unique and thus stand out.

In my opinion, our project met all these requirements. The absence of a traditional sports core was made up for by creating numerous rooftop terraces, which can also be used for physical activities. As for the design code: the Garden Quarters feature a significant proportion of ceramics on the façades, mostly brick–we also used ceramics, but a more expensive, glazed type. We spent a long time selecting the right shade, with a metallic sheen and iridescence, and ensured that the Chinese manufacturers replicated it precisely. In the Garden Quarters, rounded corners with curved glass are common – we bent the glass in the cantilever of the main façade overlooking the pond. It’s transparent, offering a panoramic view of the entire central part of the complex, which is truly impressive.

Construction progressed rapidly, and I must say there were attempts to cut costs, but we firmly stood our ground and defended the quality of every detail. Just look at the glass in the console: the sealant in the joints is white, and the silkscreening, which hides the inter-floor slabs, is composed of tiny symbols of the school, also in white.

Thirdly, the site was not 100% suitable for a school building. It’s constrained in terms of sunlight exposure, with very difficult conditions and no space to place a proper sports core. Finally, the school building was meant to serve as the final highlight of the Garden Quarters, a sort of “cherry on top”. On the one hand, it had to adhere to the design code, but on the other, it had to contribute something unique and thus stand out.

In my opinion, our project met all these requirements. The absence of a traditional sports core was made up for by creating numerous rooftop terraces, which can also be used for physical activities. As for the design code: the Garden Quarters feature a significant proportion of ceramics on the façades, mostly brick–we also used ceramics, but a more expensive, glazed type. We spent a long time selecting the right shade, with a metallic sheen and iridescence, and ensured that the Chinese manufacturers replicated it precisely. In the Garden Quarters, rounded corners with curved glass are common – we bent the glass in the cantilever of the main façade overlooking the pond. It’s transparent, offering a panoramic view of the entire central part of the complex, which is truly impressive.

Construction progressed rapidly, and I must say there were attempts to cut costs, but we firmly stood our ground and defended the quality of every detail. Just look at the glass in the console: the sealant in the joints is white, and the silkscreening, which hides the inter-floor slabs, is composed of tiny symbols of the school, also in white.

Let’s take a closer look at the school.

This is the first school built in Khamovniki in the last 25 years.

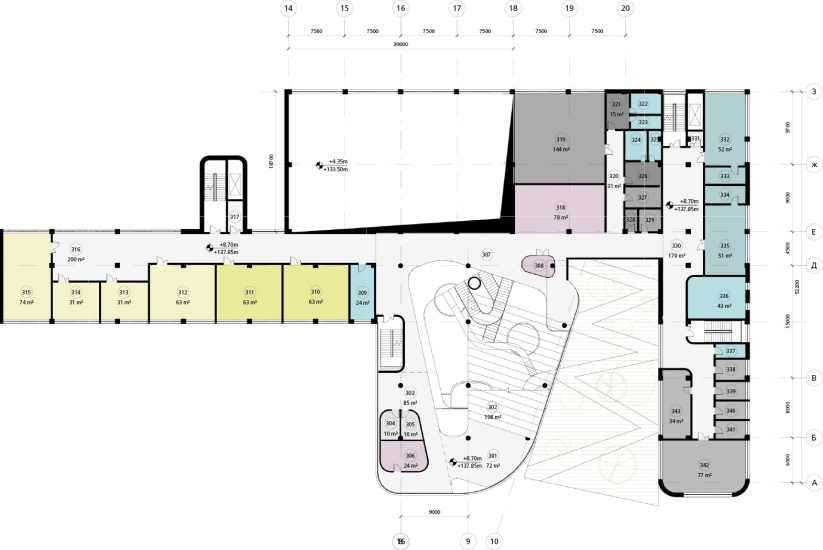

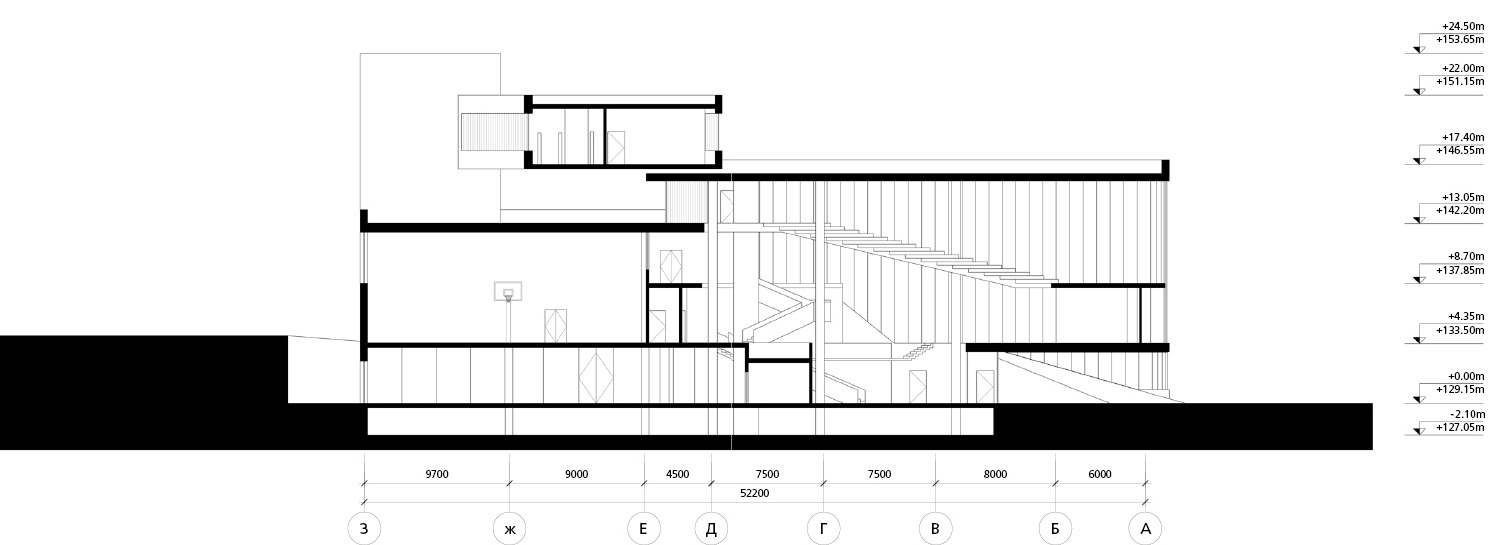

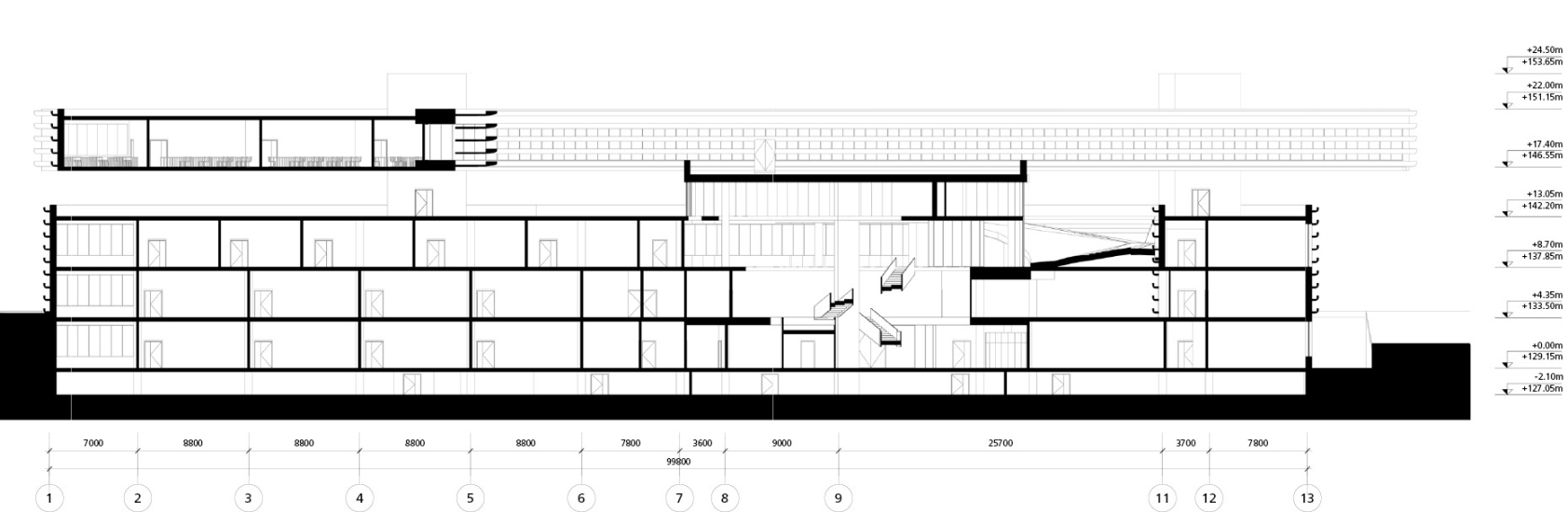

Its layout is complex, largely shaped by the land site it occupies. The rear buildings, where most of the classrooms are located, stretch between Sergey Choban’s “folded” house and Block One, running parallel to 1st Shibayevsky Drive. This side is where the parents’ cars arrive, and due to the elevation differences, a significantly sunken courtyard has been created relative to the city streets. This courtyard is designed for play and sports activities and is adjacent to the double-height gymnasium.

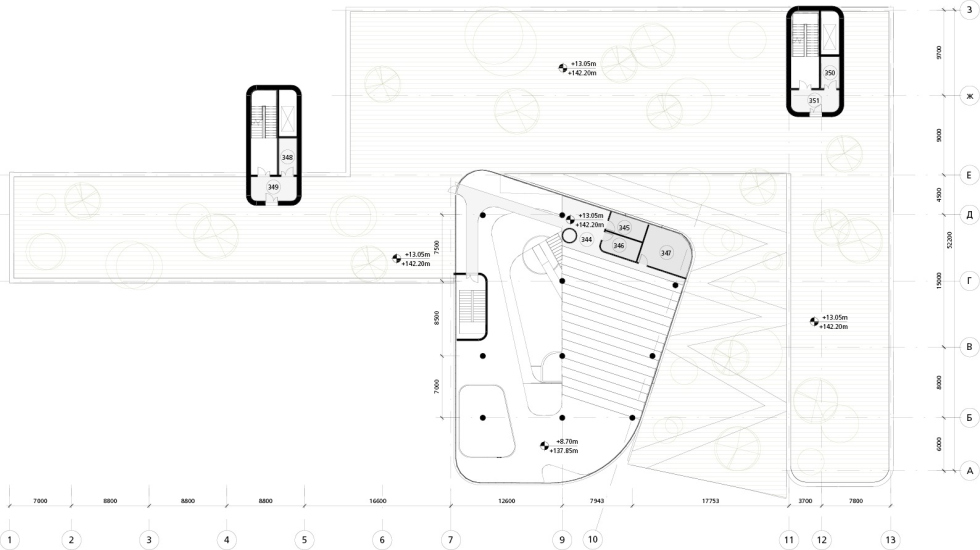

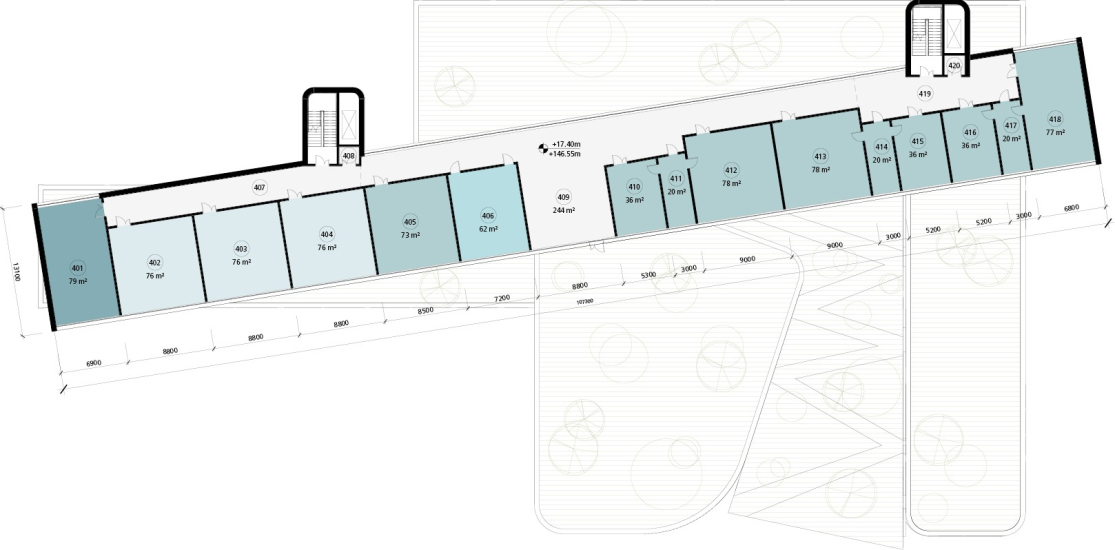

[Important note: The plans and sections presented in this article correspond to the 2020 competition project and represent the school’s implemented layout only in general terms, though they illustrate many of the fundamental approaches to organizing its space]

The left building, elongated to the northwest, is allocated to the primary school, giving it its own private and calmer space. The middle school, subject-specific classrooms, and workshops are located to the right, including in the transverse building as well as in the “beam” of the fourth floor. The glass-fronted classrooms are oriented for better light exposure relative to the lower floor and face south-southwest, while the corridor connecting the classrooms is essentially a bright glass gallery facing northeast.

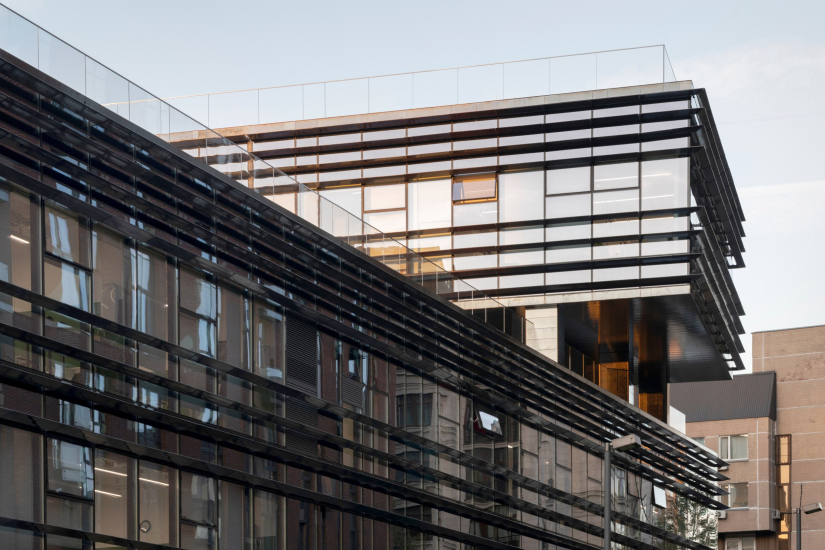

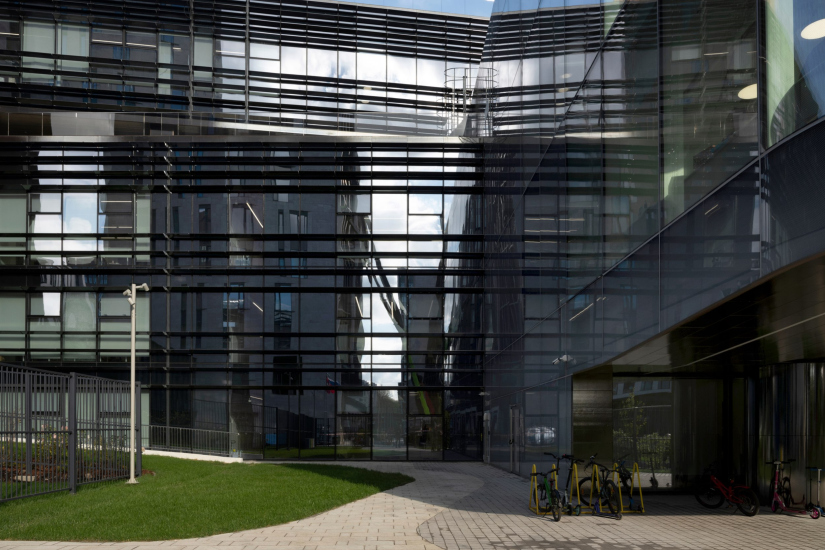

Facing the main public space of Garden Quarters and the pond are two volumes positioned perpendicular to this axis. Essentially, they are large “nose-like” buildings with an open amphitheater between them. This arrangement creates three accents for the school’s main façade, interacting in contrasting ways – a sort of trio: a large, glass volume to the left, with a mercury-like reflective quality, monolithic and slightly asymmetrical to emphasize the center; a similarly glass-covered but more compact, slender educational block to the right, defined by lines of louvered panels; and the open amphitheater in between, extending into a green hill that rises upward. This configuration resembles a “protuberance” of the green slopes in the central public area, a feature best appreciated when viewed from across the pond.

The school in Garden Quarters

Copyright: Photograph: provided by UNK

The asymmetry and central void embody a contemporary modernist approach. On one hand, this approach “unloads” the main façade, using contrast and pauses to remove excessive massiveness while increasing the light-exposure frontage of the two transverse buildings. On the other hand, this façade stands out, drawing attention with the paradoxical pause in place of a portico – a feature familiar from “Stalin-era” school buildings – and the ascending green slope.

Speaking of typology, this is clearly a “star-shaped-plan” school, whose main merit lies in its expansive light frontage and a central core that shortens paths within. However, the composition was adjusted to fit the constraints of the site; the “flower” developed without its northeastern petal.

As a result, the atrium’s core shifted, including into the glass cantilever, whose façade provides natural light to the interior space as well as a luxurious panoramic view from above – from the second-floor level and the steps of the amphitheater.

Equally important is the fact that the “glass cantilever” offers glimpses into the school’s interior from the outside. While the façade includes a significant amount of glass, with ample lighting inside, most of it is semi-obscured by louvers, giving only the impression of life within.

The school in Garden Quarters

Copyright: Photograph: provided by UNK

The main glass volume, however, genuinely reveals the school’s internal structure – from the exposed communications on the ceiling to the amphitheater, which daringly “floats” in the space between the third and second floors. This floating effect harmonizes, when viewed in profile, with the open amphitheater outside.

The school in Garden Quarters

Copyright: Photograph: provided by UNK

A stage is located on the second-floor balcony in front of the amphitheater – a rather unconventional solution. This stage can be enclosed by curtains that serve both as a backdrop and as drapes, so that during performances or rehearsals, it’s clear from the outside that something is happening inside.

Thanks to the large span, white color, and lack of visible supports, the amphitheater appears slender and truly floats, even though the supporting surface is quite thick. On its underside, circular white light fixtures are embedded. These evoke Alvar Aalto’s library in Vyborg, though in this case, the light is artificial.

Round light fixtures extend their motif throughout the space: visible on the atrium ceiling through the glass like constellations, they also appear as circular lamps embedded in the lawn of the slope.

The amphitheater’s neighbors are the staircases. Entering beneath the low cantilever through a modest-looking hall, you’re struck by how the space expands dramatically upward, interwoven with staircases connecting balconies and hanging islands. It’s reminiscent of Hogwarts, evoking thoughts of whether these balconies and islands might shift their positions at night, as they’re frozen asymmetrically, like in a game of “statues”.

At ground level, there are several islands of meeting rooms, also white, surrounded by Corian benches and plants from a winter garden.

This creates an entire system – a complex, multi-layered, “tied together” space spanning the building’s full height.

In addition to the amphitheater and social areas, the atrium includes a coworking space and a library. Oval windows from adjacent rooms open into the atrium.

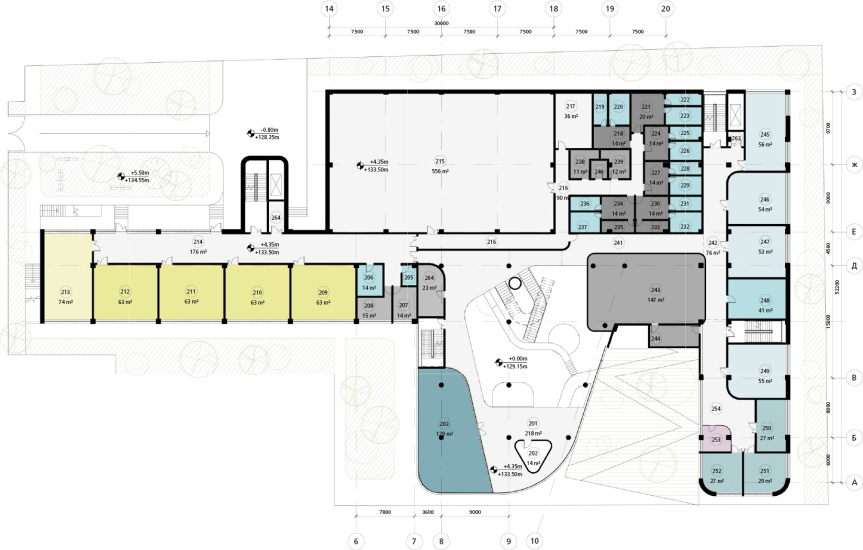

The ceramic cladding on the façades appears black, but it actually has a metallic sheen. This creates a kind of visual deception – ceramics are ostensibly akin to brick, yet when coated with a metallic glaze and “assembled” into louvers, they resemble metal – at least on the surface. Walking by, the glass school buildings seem to be enclosed in energetic metallic grids or meshes. On the main façade, the louvers are curved, while on the rear and side façades, they form angular and somewhat brutal structures. In essence, at first glance, the louvers appear metallic.

At the entrance under the main cantilever, things are slightly different.

The cantilever isn’t very high, but its deep overhang provides excellent protection from the rain. It appears slightly lifted upward, as if with an ever so slight effort – indeed, such an effort seems plausible given the cantilever’s significant span. The entrance resembles a cave, with particularly striking compact round columns supporting the cantilever right at the school’s entry. These columns, also silvery, are made of the same ceramic material as the cantilever. Together, they create a unified, subtly shimmering space above and in front of the entrance – sculptural and impressive.

There’s something about these columns that recalls the symbolism and modernist styles of the early 20th century. Short and “enigmatic” columns like these were widely used at the time. Unlike the thin, elegant columns of the avant-garde and modernism – whose “relatives” we can observe inside the atrium – these columns possess a certain brutal charm. They resemble some kind of fairytale “guardians” at the castle’s entrance. This brings to mind how the architects from UNK, while working on the “New Perspective” school project, chose the “Sherwood Mansion,” a late-modernist building by Nikolai Butusov, built in 1911, for their office and restored it. To me, at least, it seems there’s a resemblance between the glass cantilever and the glazed ceramic “trim” reminiscent of modernist majolica.

So! The school has been completed and, while not yet at full capacity – maximum enrollment has not been reached – it operates quite intensively, running until 8 PM with extracurricular activities, additional classes, and more.

Initially, it was planned as a school affiliated with MGIMO, but the newly constructed building now houses the private school “New Perspective”, an independent educational institution (its founder being the Region Group). That said, according to my information, the school is already collaborating with several universities, including MGIMO.

The building has been well received; even Julius Borisov has positively reviewed the interior design, created by Elena Aralova of ED Architecture. The interior predominantly features white and light tones, accented – particularly on the ceilings – with a striking magenta pink, a very flashy and trendy color.

How well, then, has this “new touch” fit into Garden Quarters complex? Opinions vary. Some say it fits well: the design code is upheld through the use of curved glass and ceramics, the view of the pond is emphasized, and the building reflects beautifully on the pond’s surface, acting as a kind of “firefly”.

Others argue it doesn’t fit: they believe a simpler volume with a cantilever raised higher would have been more appropriate.

As for me, I’d say this: yes, the building fits into the surroundings – but it fits through contrast.

Like a “young rebel” a representative of a new generation, the school joins a project that began long ago and developed by its own rules. Although not all by the same rules: let us recall the building in the western part of Quarter 4 designed by Andrey Savin and his “Art-Blya” company. If you look closely at it and think for a moment, you’ll notice how the asymmetrical glass cantilever of the school seems to interact – or, should I say, slyly “wink” – diagonally at this building. These two structures echo each other with their light-turquoise hues and the “nose” shape, slightly turned to the side. Of course, the school’s glass façade is more austere and more structured. But the diagonal connection is still hard to deny.

The second distinctive feature is the use of hills, terraces, and greenery. Throughout Garden Quarters, an abundance of greenery was planned and realized, particularly in the early stages. There are also hills in the courtyards and multi-level terraces. But here, in the school building designed by Julius Borisov, the amount of greenery and terraces was envisioned to be far greater than in the surrounding areas. This, too, seems like an attempt at competition: within an ultra-modern, meticulously designed, and executed complex, to create something even more modern, more technically advanced, and even “greener”.

Green roofs are still planned for implementation; we’ve seen the hill. However, green façades, unfortunately, were canceled in this project. Yet, the same architect, Julius Borisov, demonstrated in the Zemelny Business Center that this idea is perfectly feasible – plants there grow and even change color in the fall... Incidentally, I believe there is much in common between these two UNK projects: apart from the greenery and rounded corners, there’s also the metallic shine combined with glass. The school administration corrected me, saying that a school is a school, and it’s inappropriate to compare it to an office building. However, I would argue that I’m not comparing the function but the image and architectural approach. After all, this is my personal evaluative opinion; it has a right to exist. There is indeed a lot in common between the two buildings – high quality, conciseness, brilliance... Only there it’s metal, and here it’s ceramic.

Ceramics serve as the foundation for another contrast here, that contrast being horizontal versus vertical. Sergey Skuratov set a vertical rhythm in the center around the pond, uniting the stories of buildings with the façade grid. Later – possibly influenced in part by the trend set by Garden Quarters – this theme spread across Moscow and then all across the country, becoming overused and, frankly, tiresome. Let’s hope that our project in Khamovniki wasn’t the culprit. The fifth residential area follows the same rhythm, often mistaken for Skuratov’s buildings (much to the architect’s dismay, as he himself recently remarked).

Julius Borisov’s school, however, could never be confused with Sergey Skuratov’s buildings. Some might call this an issue, while others might see it as an advantage.

Although the school building adheres to several of the design code’s guidelines, as mentioned earlier, its interpretation conveys a degree of separation from them – a certain daring independence, a kind of teenage rebellion under the motto, let’s say, “I’ll do everything my way!”

There’s a lot of glass in Garden Quarters, but no large glass patches or volumes? Well, our school will have them! And so we get this large “sculptured cantilever”, like a bubble blown by the school toward the respectable urban quarter. Of course, this “insolent bubble” is still a polished, immobile, beautiful structure of expensive glass – not quite in Alsop’s style, but still, on reflection, there’s a certain nuance here.

Garden Quarters have almost no horizontals in them? Well then, take this – everything in the school building, aside from the glass volume, will be horizontal.

And I must say I find the horizontal volumes with louvered panels to be the most compelling aspect of this building. They don’t hide their boldness. But then again… well, they do hide it a bit, at least from the main façade. But from the back, they don’t. Approaching from Usacheva Street, we see the black, striped, jutting, and criss-crossed “beams” of the third and fourth floors. And this is exactly the way it should be – because they teach teenagers in there, and teenagers need freedom and audacity. In my opinion, this is the best advantage of the project, even if it’s not the most obvious or formally prestigious one.