Maia Maisuradze, Director of the Primakov School and the Vzlyot Educational Center

Our mission is to create a motivating educational environment where children not only acquire knowledge but also develop visual literacy and aesthetic taste. They spend up to 12 hours a day in our full-day school, so the space around them must be inspiring – encouraging creativity, leadership, and elegant solutions to complex problems.

Our academic year consists of five modules spanning 10 months. Starting in Grade 5, students are divided into “houses”, like in Hogwarts – North, South, East, and West – which compete in both individual and team challenges. We have a digital school that enables athletes and musicians to study through blended learning, combining online instruction, in-person intensives, and tutor support. Additionally, we have established the “Vzlyot” Educational Center to support and develop talented children from the Moscow region. Its specialized programs in science, arts, and sports are free of charge, and over the past five years, more than 22,000 students have participated in them in person.

Our academic year consists of five modules spanning 10 months. Starting in Grade 5, students are divided into “houses”, like in Hogwarts – North, South, East, and West – which compete in both individual and team challenges. We have a digital school that enables athletes and musicians to study through blended learning, combining online instruction, in-person intensives, and tutor support. Additionally, we have established the “Vzlyot” Educational Center to support and develop talented children from the Moscow region. Its specialized programs in science, arts, and sports are free of charge, and over the past five years, more than 22,000 students have participated in them in person.

The educational center “Vzlyot” was established in the Moscow region following the model of the “Sirius” center. Given this, it is no surprise that Nikita Yavein and Studio 44 – the architects behind the Sirius buildings in Sochi – were invited to design the second phase of the school. Their portfolio includes numerous campus projects for various cities under state programs, such as ITMO University, as well as educational institutions like the Eifman Dance Academy in St. Petersburg.

We have previously covered the school’s design project, but now we can see it in reality – and that’s exactly what we are doing now.

It is undeniably impressive, not least because of the spaciousness made possible by its suburban location. I walked the entire site and got quite cold. The architects note that the original plan envisioned an even wilder arrangement of the buildings, which was later on made more restrained. However, this adjustment is not perceptible in the final layout.

It’s clear that the “city” campus concept – long tested and cherished by the architects of Studio 44 – has been realized here on a noticeably grander scale. This idea was particularly evident in the second-phase building of the Eifman Dance Academy in St. Petersburg, where the atrium functions as a theater foyer, a school courtyard, and an urban square – all rolled into one. However, in the historic center of St. Petersburg, such a school had to be expectably “compressed”. Here, in contrast, it has expanded – let’s say, in a thoroughly Moscow or even suburban Moscow fashion – fully spreading its wings.

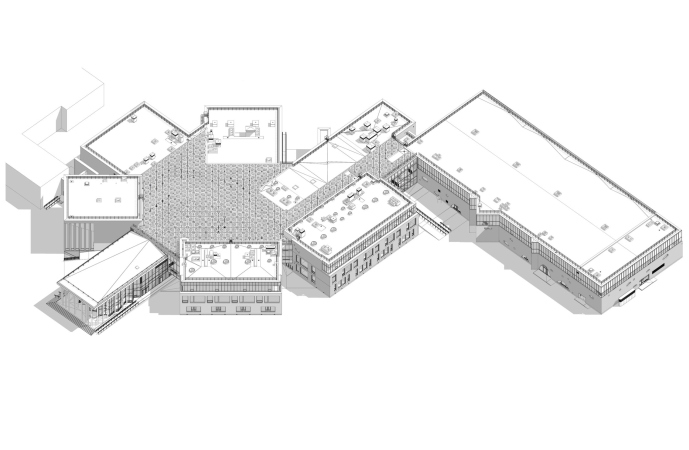

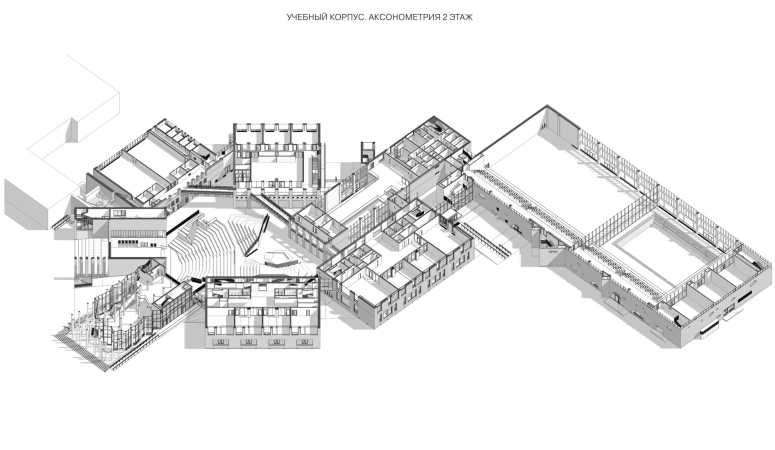

All the buildings – seven, plus a separate sports facility – are connected within a heated perimeter and are arranged around the atrium core. The functional layout is exceptionally clear, organized into distinct blocks: three for “Sciences”, one for “Arts”, a cafeteria, a stage, and an entrance lobby with a waiting area and a mezzanine café for the parents – before the turnstiles, in the warmth. Oh, Gosh, why don’t we see things like that in EVERY school?

We’ve grown accustomed to atriums, now often seen as an overused, obligatory feature.

But here, it’s not just an atrium – it’s truly a covered city square.

I hope the architects won’t take offense at a comparison with Gostiny Dvor, but that’s the first analogy that comes to mind – at least for those who visit it for architectural and other exhibitions. Yes, the project was controversial in its time, but how beautiful it is, especially on a sunny day!

Similarly, in this school, the architects have fully embraced the advantages of a large-span transparent roof – sunlight bouncing off the glass surfaces, the delicate white lattice of structural elements, and the abundance of natural light.

Yet what’s particularly important is that the airy white framework doesn’t appear rigidly constrained within a rectangular perimeter of the walls, the way it is done in Gostiny Dvor and many other places. Instead, it truly “floats”, uniting the volumes of this “city” like a kind of “wing”. It even has its own amphitheater-like space and a street leading to the sports complex. What’s fascinating is that the two-story scale remains intact throughout; as we walk, we remain “under the open sky” of the roof structure. In addition to the main square, smaller plazas also emerge here and there, framed by staircases and first-floor galleries.

There are also footbridges on the second floor level, with slightly slanted floors – hello, Renzo Piano! – and ventilation outlets shaped like small spheres, reminiscent of those seen in Moscow’s GES-2. Later, when walking around the building and discovering weathered steel pipes, the resonance becomes complete – not with any specific work by Piano, of course, but with the entire high-tech and deconstructivist movement.

Primakov School, 2nd phase

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Naroditsky / Studio 44

This building is not an imitation, yet it does employ techniques that have been widespread in European architecture for the past 50 years but are less common in Russian practice. This is where the building’s “recognizability” comes from. No, it’s not a replica of GES-2, but it is most certainly its “relative”.

Why do I insist it’s not an imitation? In general, discussions about architectural mimicry and architectural language are both popular and necessary. Ignoring this issue – one that regularly flashes like a red light in everyone’s mind – would be wrong. It’s a concern that should be addressed. In this particular instance, the answer is almost obvious. And here’s why: if you examine the facades, you’ll notice echoes of, say, Mario Botta’s work – in the parabolic arches and the scattered round and oval windows punctuating the brick façade, elements firmly rooted in early postmodernism. Or take the triangular protrusions of the buildings – they instantly bring to mind the Taganka Theater. Even the combination of an almost solid brick wall with a glass top strongly recalls “the classics”.

Primakov School, 2nd phase

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Naroditsky / Studio 44

It goes without saying that these techniques have long been a staple of Nikita Yavein’s work. There’s no need to list projects – suffice it to say that he proudly displays a full-wall circular window in his own office: "Yes, I love round windows; they appear in each and every one of our projects”. And this building has them too. Round windows, after all, are a time-honored motif, which can be traced from Gothic architecture to Constructivism.

It’s a wonderful thing when a building evokes not a mere repetition of something past, but rather a creative engagement with an arsenal of techniques and approaches.

One more detail worth mentioning: the scattered, varied window sizes on the facades even “legitimize” the asymmetrically placed ventilation grilles. It would be nice to see those arranged more neatly, but their “response” in the form of windows – how fitting it is! Everything falls into a system of visual echoes because of it.

The architects lament that the construction timeline was shortened by a year. This, incidentally, is a sign of the times: the Kamal Theater’s schedule was cut by a staggering year and a half.

As a result, the school opened in 2023 with the facades of some buildings still unfinished.

There are other flaws as well, one of the most noticeable being that the atrium’s structural framework was never meant to remain exposed – it was supposed to be covered, according to the original design. The necessary fixtures for mounting the cladding were never implemented either. Still, its eventual installation remains a possibility, whereas the cheap concrete tiling on the façade, replacing the intended brick, is likely here to stay.

However, flaws like these are almost inevitable, especially when timelines are compressed. In this case, however, they are of secondary importance because the architecture was conceived with a focus not on decorative elements but on spatial composition – the logic of how the building is structured and how people move through it. In this regard, the school made the perfect choice by bringing in Studio 44 – a firm that both knows how and is capable of delivering.

Moreover, the facades do not disappoint, because in this building, what truly matters is inside. So, let’s return to the atrium – we’re not finished with it yet.

The atrium of the Primakov School is, of course, an experimental space for us: is it even possible to combine a school recreation area with a hall that seats 900 people? This idea was largely inspired by our client from the very beginning. The school genuinely needed a large hall for events. During school hours, the atrium functions as a recreation area, an indoor school courtyard, but several times a week, it hosts master classes, meetings, and conferences.

The most interesting part was seeing how the students would interact with the space and the atrium’s terrain. It’s very gratifying to see that everything works as intended: during breaks, the children sit on the “hills”, casually scatter their backpacks around, and genuinely enjoy spending time here. In the modern horizontal-network educational model, recreation areas take on primary importance and become the key spaces of an educational institution – the center of informal communication.

I believe that school buildings are where architecture has the greatest influence on shaping and educating a person: you spend 10 years of your life in school, and it is often the first public building you come to know in detail. You want it to be interesting. And in this, we fully align with the school’s director, Maia Maisuradze. Six months after the opening, she told me – and this is probably the greatest compliment we’ve received so far – “The space of the school turned out to be so open that the children studying here will undoubtedly grow up to be completely different people”.

The most interesting part was seeing how the students would interact with the space and the atrium’s terrain. It’s very gratifying to see that everything works as intended: during breaks, the children sit on the “hills”, casually scatter their backpacks around, and genuinely enjoy spending time here. In the modern horizontal-network educational model, recreation areas take on primary importance and become the key spaces of an educational institution – the center of informal communication.

I believe that school buildings are where architecture has the greatest influence on shaping and educating a person: you spend 10 years of your life in school, and it is often the first public building you come to know in detail. You want it to be interesting. And in this, we fully align with the school’s director, Maia Maisuradze. Six months after the opening, she told me – and this is probably the greatest compliment we’ve received so far – “The space of the school turned out to be so open that the children studying here will undoubtedly grow up to be completely different people”.

The unique feature of the atrium and amphitheater here is that they have “merged” and developed extensions. The stage is housed in a separate volume, one of the eight campus buildings. From the outside, it forms a golden frame-like portal, inviting thoughts of open-air performances. The rear wall of the stage is glass – it can be left transparent or closed off. What’s more, the stage itself can be temporarily separated from the amphitheater and atrium, transforming it into a lecture hall or an event space.

In daily use, however, the amphitheater descends toward the stage, with a significant change in elevation – it appears as an extension of the atrium, sunken into the ground, a kind of “protuberance”, which makes sense given all the functions it serves. In 2023, this very stage hosted the “Teacher of the Year” award ceremony.

But the stage, along with the amphitheater clad in oak, continues with similar stepped volumes that rise above the atrium floor. One can imagine a Greek amphitheater built into a slope, with a couple of hills towering above it.

This design approach – sinking the main steps downward while adding extra “hills” above the basic level – creates a wealth of possibilities.

First, during large events, these hills can accommodate extra spectators. Second, the atrium space – immense in scale – feels comfortable thanks to the zoning created by these additional volumes. And finally, there are functional spaces beneath the “hills”: under one, there is a café with exposed concrete walls; under the other, there is a similarly designed library. Children can grab a book and settle on the amphitheater’s steps to read.

Atop the library sits a white grand piano, where students come to play in the evenings – provided they know how to play. I found it amusing to hear the story shared at the school about a second piano, a black one, positioned on the stage: it was rented for concerts because moving the white piano down every time turned out to be more expensive than simply paying for a rental. So now, the atrium has two grand pianos – one white and one black. A perfect Ying Yang harmony.

Another striking moment – on the way to the sports halls, you can glance into the cafeteria. It’s a double-height space, unified by a whale-shaped wooden pendant light with embedded spotlights. The entrance is a narrow, yellow passage lined with rows of sinks, and right next to it, a “street” leads toward the sports facilities.

Naturally, inside, the classrooms feature floor-to-ceiling glass walls, while the gym and swimming pool are both impressively spacious. The classrooms are well-equipped, and the hallways include co-working booths – some for two people, others for one – where a tutor can meet with a student for a one-on-one session, or a teacher can conduct an online lesson without occupying an entire classroom.

But what captivated me the most were two things. First – the ceramic façade. The concept and execution were led by Ivan Kozhin, a partner at Studio 44 who led this project. The ceramics adorn the inner façade of the volume that houses the arts-and-cultures wing. While the technique itself harks back to Art Nouveau, the accordion-like treatment of the surface evokes something closer to Chagall. The abstract “carpet-like” inserts in deep, vibrant tones provide a striking contrast to the ceramic figurines displayed in front – student creations that leave no doubt about the presence of a kiln at their disposal.

Similar ceramic inserts can also be found on the exterior facades, in the stairwell niche, where turquoise tiles immediately bring to mind classic Art Nouveau references. At the same time, they reinforce the dialogue between the interior and the exterior.

Primakov School, 2nd phase

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Naroditsky / Studio 44

Second – the hypostyle hall formed by the white portico at the main entrance, enclosed within a glass shell. Notably, the “warm loop” of the glass façade follows an asymmetrical zigzag pattern in plan, echoed by the irregular placement of the columns.

At first glance, it’s a portico – a formal, ceremonial entrance – but light, almost playful. Inside, however, it gleams gold, much like the stage canopy next door – visible through the gaps between the pylons, half of which are turned at a 45-degree angle. The effect recalls not only the Taganka Theater but even more so Moscow’s Paleontological Museum.

The second phase of the school completely surrounds the first phase – designed by Feierabend Architekten and Walters Architects and completed still back in 2017. The main entrance to the new building forms a logically coherent ensemble with the “copper” courtyard of the first phase – as if it had been planned this way from the outset. In reality, the composition developed organically over time. The first-phase building now houses the lower grades, while the new one accommodates students from grades 8 to 11.

The master plan. Primakov School, 2nd phase

Copyright © Studio 44

To the north and south of these two academic buildings stand the residential quarters of the campus. Given the school’s mission of drawing students from across the country and the Moscow region, these dormitories are indispensable. And they are designed, true to Studio 44’s signature style, with atriums at the core of each volume. In the northern section, four square-shaped dormitory buildings house the students. The facades are uniform – they are brick – but the window frames are made deliberately, even emphatically, different in color: yellow, blue, and green, which makes orientation much easier for the students.

The faculty building – let’s not forget, the school was designed from the outset to collaborate with teachers from across Russia and the world – has a circular plan. Once again, this is a form Nikita Yavein favors, a kind of tower reminiscent of Moscow’s Gazgolder, allowing for bold and monumental sculptural variety – a recurring motif in Nikita Yavein’s projects.

At the atrium’s heart, beneath the glass ceiling grows a living tree. “It can’t quite settle on the seasons, shedding leaves whenever it pleases, but it’s nonetheless alive” Ivan Kozhin boasts. This isn’t the first time Studio 44 has integrated trees into interiors – one might recall the exhibition at the General Staff Building or the 2023 “Architecton” festival. A winter garden, yet without a palm tree this time around.

***

Thus, we see that the Primakov School is truly one of those “educational institution projects” shaping a new discourse in the architecture of learning environments.

Yet, if I were to highlight the most striking impression left by this building, it would be:

– Not the layout, which reinterprets the “star-shaped” school typology to maximize natural light exposure;

– Not the facades, with their “megalithic” austerity and triangular protrusions marking the plan’s directional axes;

– Not even the presence of an atrium space, significantly more developed than usual;

– Nor the staging of a miniature city beneath the “white wing” of the overarching roof, convincingly emphasizing both the building’s complexity and cohesion.

The most important aspect, in my view, is that the second-phase building, designed by Studio 44, is all about its interior space. Art historians often say of Byzantine churches that their facades are secondary to the emotional, compositional, and structural qualities of their interiors. This is not to suggest that the exterior has been neglected – there is intrigue there too, from the white portico with its accordion-like glass to the deep-framed loggia behind the stage. However, these elements merely hint at certain functions, while the essence of the concept and the “program” unfolds, in all its complexity and theatricality, within. The heart of a school building must lie within. And in this particular instance this is exactly the case.