Prison Yard. Garden of the Inmates’ Wing, Spaso-Yevfimiev Monastery

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru 06.2025

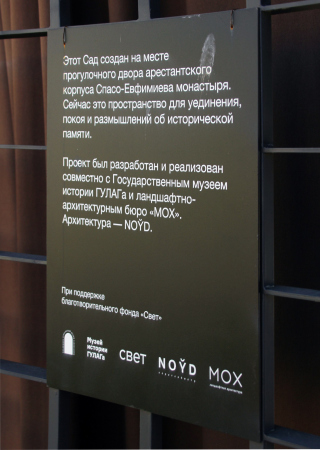

Thanks to the Vladimir-Suzdal Museum-Reserve, its director Ekaterina Pronicheva, and the Gulag History Museum, the place has been restored, an exhibition opened, and two “prison courtyards” arranged. “The creation of a new permanent exhibition here was supported at a meeting of the Interdepartmental Working Group for the Implementation of State Policy on Commemorating the Victims of Political Repression in 2023”, the museum website reports.

The architects: NOῨD Short Film. Landscape: MOX landscape architects.

The gardens opened in October 2024, but I visited them in June, when everything had grown wild and bloomed – something that, for a landscape project, is probably an advantage. They say the garden needs another couple of years to fully mature.

Still, it looks good already.

There are two courtyards, designed in opposite ways. The first one, lying on the visitor’s path – the exhibition itself is housed in the actual prison buildings, in the farthest corner: past the cathedral, right to the end, to the cells, then left and left again – So! The first courtyard, leading into the exhibition on the prison’s history, is made deliberately austere.

Prison Yard. Garden of the Inmates’ Wing, Spaso-Yevfimiev Monastery

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru 06.2025

One large tree has been preserved, a concrete path with ostentatiously jagged edges laid, and wild grasses grow on either side of it. Now, in summer, the grasses have gone to seed, creating silhouettes and sharp shadows, especially in contrast with the tree. It’s a serious prelude to a severe exhibition – you enter, and to the left you see the Tsarist prison, to the right the Soviet one, which existed “until the Gagarin era”, so to speak.

The second courtyard, by contrast, definitely allows the soul to rest after such heavy material. There is a popular belief that you should not tempt fate by acting such things out on yourself, lest you invite them upon you. And yet, you cannot quite chase these thoughts away, imagining what it would be like to be a prisoner here. “Well, it’s a good thing that here we can not just enter, but also exit again” – jokes the wonderful museum guide Lyubov Rusanova. A good thing indeed!

So! This second courtyard is more scenographic. A wooden platform runs down the center, with metal grilles to either side. Plants push through them, but you can also walk across them – and inevitably you think about how easy it would be to trample these daring shoots.

Prison Yard. Garden of the Inmates’ Wing, Spaso-Yevfimiev Monastery

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru 06.2025

The planting here, I am told, is all “ruderal”. “Allochthonous” means wild, but not native – in other words, weeds. A metaphor for the “weeds of society”, rejected and “uprooted” by one community or another, often for political reasons.

And June shows most clearly that these plants can be very, very beautiful. The peach-leaved bellflower, for example, is a stubborn weed, but lovely in itself.

Different associations come with the Maltese cross (Silene chalcedonica), or campion, as well as maiden pink (Dianthus deltoides), both from the carnation family.

Here they appear like drops of blood on a dense scattering of ceramic brick shards. These shards serve both practical and symbolic purposes: drainage, and fragments of ruined lives. Among the partly ruined brick walls of the courtyard, the metaphor is especially palpable. One might even think these were remnants of collapsed vaults – but no, the yard was long open. If there ever were coverings, suggested by the surviving gable, they were most likely wooden rafters.

Thorns and spiky plants play their obvious part. But perhaps the main figures of this landscape are what I’d call “crooked fir trees”. The word comes from a children’s rhyme, but here, alas, it’s anything but funny – and it’s not clear if it’s even appropriate. Their resemblance to the silhouettes of broken, stooped figures bent by years of imprisonment is unmistakable.

At the end of the wooden walkway stands the “black box” exhibition space. Inside, one can see or fail to see a scaffold.

This prison courtyard makes a strong impression – stronger than the Apothecary Garden, another project by the museum in the same monastery near the entrance.

What we see here is a “telltale” landscape, with plants that speak. For landscape art, this is nothing new; even for an average visitor it is probably easier to seek symbolism in plants than in architectural forms. After all, everyone has at some point plucked daisy petals to divine love, or pondered whether to bring a girl a white rose or a red one.

On the other hand, if you think about it, the theme might have come across even more powerfully if there had been no plants at all – if the yard had been poured over with concrete, with a few dandelions forcing their way through cracks. And if, on entering, the visitor had to shut the door behind them. No, I’m not suggesting locking people in – but we understand that exhibitions about prisons become more effective in proportion to how much they emphasize the feeling of confinement.

Here, it’s the opposite. Nobody wants to frighten the visitor. On one hand, that’s bad – the impact is diluted. For some, the message barely sinks in at all. On the other hand, perhaps it’s better this way: some of us need precisely that sense of hope that shines through in the weeds growing up through shards of brick. Life everywhere; we will live.