And yet the fact remains: despite my personal distaste for the cutesy nickname of “Patriki” (yak!), redolent of endless TV series about the dramas of the beautiful life, the area has indeed become exceptionally prestigious and popular. Very much so. In the evenings, Malaya Bronnaya is so packed with people that you can hardly squeeze through – just like Nevsky Prospect in St. Petersburg. Practically the Champs-Élysées of the Belle Époque.

From the Patriarch’s Ponds, it’s a short walk to many places: Pushkinskaya Square, the planetarium, the Moscow Art Theatre, and more. But there’s another feature too. Sometimes the bustling social life, especially at night, spreads across the whole district. At other times, the central streets may be noisy while the nearby lanes stay calm. If you want to go out, all the so-called “attractors” are just steps away; if you want to hide away instead – welcome home.

It is no surprise, then, that over roughly 25-30 years, through the 1990s and 2000s as the district gained and consolidated its popularity, many new houses were built here. The most famous is, of course, the “Patriarch” house on the Garden Ring. But there are plenty of others. A closer look reveals that almost a third of the buildings are relatively new – some blending into the streetscape, others designed by Sergey Tkachenko (these are different), and still others flamboyantly postmodern in the Yuri Luzhkov era style: sometimes in the shape of a ziggurat, sometimes a lily. There are also more recent insertions, though not so numerous.

All the more intriguing, then, is the project by Andrey Romanov and Ekaterina Kuznetsova designed for Sminex in Bolshoy Palashevsky Lane – fragmentary mentions of it have only recently surfaced in various sources. Now we have the opportunity to examine the design more closely, if not in every detail, and to understand what exactly is planned for Bolshoy Palashevsky, numbers 11-15.

First of all, the site is just steps away from Tverskoy Boulevard and Novopushkinsky Square, where a large restaurant and cultural complex by Tsimailo, Lyashenko & Partners is currently under construction. Second, the location itself is interesting: Palashevsky Lane takes a sharp 45-degree turn here, eventually becoming Sytinsky Lane, which, in turn, leads directly to the boulevard.

And finally, we see that the plot is currently occupied by three small plastered houses in bright colors – bright yellow, green, and pale yellow – complete with rustication and mansards, each just two stories tall.

At first glance, turning into the lane, one might think these are remnants of old Moscow, while in fact nothing could be further from the truth.

Rather, these houses belong – if one may put it this way – to the fairy tale of Old Moscow. That fairy tale was shaped in the 1970s and 1980s through magazines, paintings, memoirs, and cartoons. It was later developed further, including in regeneration projects: new buildings erected on sites emptied by earlier demolitions. The goal was to regenerate the urban fabric, so the architecture itself could be almost anything, with only height restrictions to keep it in check. Thus, in the early 1990s, three office buildings appeared on the site of demolished income houses of the Moscow type – buildings that resembled townhouses, but with the characteristic bulkiness of postmodern form. They were designed, as far as one can tell from available information, by a team led by Andrey Meerson, including Massimo Cademartori, Massimo Polidori, and Marco Farolfi.

An interesting case indeed! Still, the three buildings of the early 1990s are not officially listed as monuments, and cannot claim protected status. Accordingly, two or three years ago work began on larger-scale concepts for the site, in keeping with the height of neighboring houses from the 1910s.

In 2023, Sminex held a closed-door competition. The winning design was submitted by Andrey Romanov and Ekaterina Kuznetsova of ADM architects.

From the very beginning, we built on the principle first tested in our project with the same client at Malaya Ordynka 19: we divided the volume into three distinct facades to make its perception livelier, more engaging, more varied, and also more appropriate for the city center, where different architectural solutions have historically coexisted side by side. Yes, this is a postmodernist approach: there is no “modernist honesty” of a precise match between interior and exterior. Instead, there is diversity, attention to detail, and, finally, a rhythmic organization of urban space – the division of a building into several volumes, each conveying different images and ideas.

We also pay great attention to details, textures, and materials, and to how they are perceived at the pedestrian level.

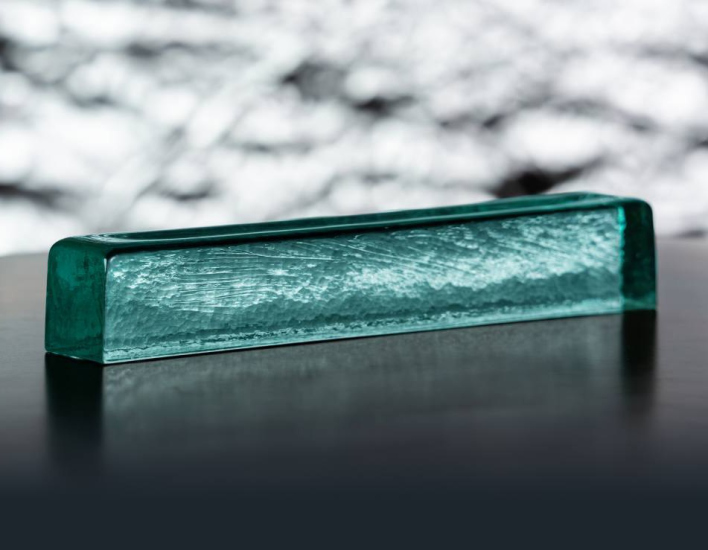

In this case, one of the three volumes had to be set back from the red line due to the insolation requirements of neighboring buildings. By retreating deeper into the site, this block gained spacious, asymmetrical terraces – a rare, practically unique solution; nothing like it exists either at the Patriarch’s Ponds or elsewhere in central Moscow. We plan to finish the undersides of these terraces with crystallized glass.

The second façade is more “material”, but its corner folds at the top so that the French balconies gradually transition into balcony-loggias.

The third façade – the one everyone particularly liked from the very beginning – will be built from glass in its natural tint, with greenish glass semi-columns. These will be manufactured according to our original sketches, with transparent joints, from six or eight whole horseshoe-shaped “shell” blocks fixed to the façade.

We also pay great attention to details, textures, and materials, and to how they are perceived at the pedestrian level.

In this case, one of the three volumes had to be set back from the red line due to the insolation requirements of neighboring buildings. By retreating deeper into the site, this block gained spacious, asymmetrical terraces – a rare, practically unique solution; nothing like it exists either at the Patriarch’s Ponds or elsewhere in central Moscow. We plan to finish the undersides of these terraces with crystallized glass.

The second façade is more “material”, but its corner folds at the top so that the French balconies gradually transition into balcony-loggias.

The third façade – the one everyone particularly liked from the very beginning – will be built from glass in its natural tint, with greenish glass semi-columns. These will be manufactured according to our original sketches, with transparent joints, from six or eight whole horseshoe-shaped “shell” blocks fixed to the façade.

What sets their proposal apart from all the other entries is its tripartite structure – a solution that, as the architect rightly notes, recalls the luxury residential development at 19 Malaya Ordynka, a building that has already become a fixture of contemporary architecture tours and earned considerable fame. It is almost surprising that no one but ADM thought to suggest it, since the site historically – and even now – consists of three distinct fragments.

On Ordynka, Romanov and Kuznetsova combined three different materials. Here, it is clear that the main role will be played by the façade of the eastern volume, visible in the perspective of the lane when approaching from the boulevard.

This is a highlight, meant to catch the eye: what is it there that glimmers and gleams? Although the volume itself is slightly shifted – angled eastward for better sunlight access – this very deviation adds a sense of plasticity. The columns and small terraces rise in a stepped pattern, one above the other, with a restrained logic and yet, in truth, in a wholly unexpected way. The green-tinted glass too – a thick, palpable volume with its natural hue – contributes to the effect.

There are no capitals or bases to these columns, nor, as the architects explain, should there be any visible joints. Each column will be made of six to eight glass blocks, horseshoe-shaped segments attached to the façade. The result is an impressive solution – a kind of glass sculpture in the natural, “ferrous” shade of the material. It is beautiful.

According to the developers, Sminex has the means to execute the project in the highest quality materials – a “sore spot” in Moscow, as everyone knows. Still, if we look at the façade of the aforementioned Malaya Ordynka 19, or at the Lavrushinsky project now being realized by the SPEECH Architects with the same developer, there are grounds for confidence in the quality of execution. These are elite-class buildings, and the value of their façades depends directly on the integrity of the materials.

The solution is truly remarkable, though a few parallels can certainly be drawn. Take, for instance, the glass “curtains” on Malaya Ordynka. At the same time, glass as a greenish mass is itself a popular medium in contemporary art and design: one might recall the Hermes store in Amsterdam by MVRDV, with a façade assembled from glass bricks. Or the columns of the Kutuzovsky-XII building by TLP – granted, they are entirely different, and the building itself is of a different character, but they are still glass columns, and thus belong in the same lineage. One might even place them in the broader series of contemporary experiments hovering between historicism and modernism – distant from both, and therefore charged with heightened tension, which makes them compelling. Consider, for example, the 19th century and the Art Nouveau period: the latter loved green majolica, and what is majolica if not glass on a ceramic base? The 19th century also made liberal use of bronze, including its natural patina – and in the neighboring building by Pavel Andreyev we see precisely a blend of references to both Art Nouveau and historicism.

The building will include a lounge, a playroom, and a fitness center – all reserved for residents. The developer describes this integration of community functions as a principle. And indeed, if we look at the building reconstructed by Ilya Utkin at Chistye Prudy, there too is a “community hub”, designed by APREL architects by adapting a historic annex.

***

If we consider the context of the Patriarch’s Ponds neighborhood more broadly, the following can be said. The area contains much late-19th and early-20th-century architecture – primarily utilitarian rental housing. It also includes many 1990s-2000s buildings in the cheerful postmodernism of Sergey Tkachenko. In places, one finds “Mossovet” construction of the 1920s and, apart from the Satire Theater, not the most sophisticated Constructivism. The impression arises that history is moving in circles – or even in spirals, like Tatlin’s Tower perched as the “cherry” on top of the Patriarch house. From simple to complex, from playful fantasy to serious repetition, and back again to something simple yet executed with costly, exclusive craftsmanship. So finely executed that passersby will want to stop to take in the details and puzzle over how it was done – solutions of this kind, I suspect, will draw the gaze of future generations just as we, as children, were fascinated by any ceramic tile we spotted on a Moscow façade.

The project was cleared by Moskomarkhitektura – just a few days ago.