The T+T Architects team has also envisioned a new route: a staircase leading up to a bridge over the railway tracks. For now, this path remains closed off by barriers, although young people are already hopping over them with ease. Once opened, the pedestrian route will provide a shortcut between the Garden Ring and Kazakova Street, enhancing the transparency of the urban territory – a perfect reflection of Sergey Trukhanov’s whole creative philosophy. We will remind you at this point that, according to the architect, his company’s name, T+T, stands for “Transparency Territory”.

Part of this pedestrian route was actually built back in the early 2000s, thanks to the wide arches of the two buildings that make up the Citydel Business Center (2001–2008). The path through these arches, descending from the Garden Ring into the office courtyard, has long led to the ruin of the old depot.

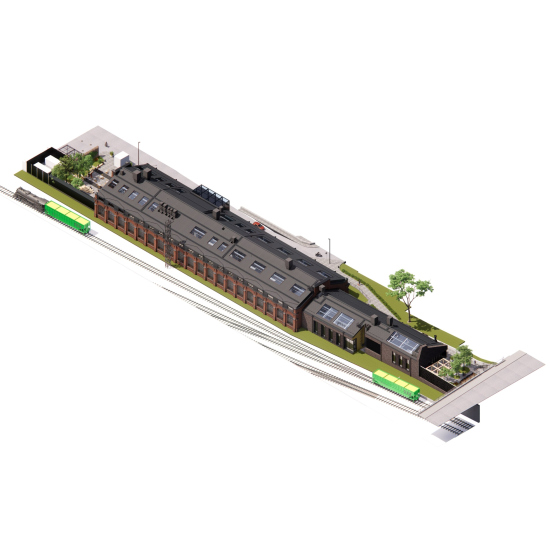

D_Station

Copyright: Photograph © Mikhail Mulach / provided by Т+Т Architects

However, this is no ordinary ruin. Lacking official heritage status, the building gained a reputation in the 2000s as a “spontaneous art squat” where informal exhibitions, concerts, plays, and performances were held, according to the architects. The creation of a pedestrian passage through the massive office complex back then seems to have served a purpose. After the 2010s, however, the depot fell completely into disuse. Now it is being reborn in a new capacity, with a landscaped pedestrian route running along its side. The enclosure of the small plaza in front of D_Station, made from pre-charred wooden planks, draws attention not only with its unusual texture but also by echoing the black-framed openings of the business center.

We covered the renovation project for the Kurskaya depot back in 2019. In addition to new public spaces and improved pedestrian connectivity, the project emphasizes the importance of reconstruction. T+T Architects are passionate about restoration work, boasting an impressive portfolio in this area. Both the client and the architects decided to preserve the depot building despite its lack of official heritage protection.

The most valuable facades, made of red brick, feature classic industrial decorative elements: large windows with arched lintels, pilasters, astragals, corbels, and sills. Not overly ornate, but not plain either, the 1906 structure was both practical and expressive.

The top floor was expanded with a mansard level clad in dark standing-seam metal, complemented by black frames. In some areas, drainpipes extend into elegant black gravel beds, which are mirrored by white stones used in the landscaping.

One striking design feature highlights the theme of ruins. The depot once had a transverse wing extending toward the city, similar to a transept. This section was demolished in the latter half of the 20th century and did not survive to the architects’ era. However, their creative solution was to preserve a fragment of the original wall encased in a glass shell – the main modern intervention and a focal display piece. This approach to ruins – preservation through display – represents a contemporary perspective. A fragment gains value when encased in a glass case, lending a 19th-century relic an almost ancient aura.

The outer edges of the broken walls frame both the glass shell and the entrance to its left, resembling columns of ruins. Their jagged surfaces naturally catch the eye, reinforcing the motif of historical layers embedded in a modern context.

D_Station, 11.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Near the entrance, the design introduces new brickwork: small, multicolored bricks harmonizing with the historic ones. Laid in a modernist zigzag pattern, this brickwork evokes the broken fragments of the old structure. Here, near the entrance, the bricks feel almost “restless”.

In the northern section, more recent walls adjoin the original 1906 structure. These are narrower, giving the building a telescopic effect, widening from north to south. The brick in this area is fundamentally different: dark and small, though not the elongated Roman style. It contrasts subtly with the historic brick, creating a harmonious yet distinguishable background. The interplay between these two materials underscores their shared terracotta roots despite their differences.

D_Station, 11.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

The new brick is smooth, dark, and modern in its simple rhythm. Emerald-green glazed inserts add a cool-toned contrast while subtly referencing the facades of Kazakov Grand Loft (2019–2022), located on the opposite side of the railway tracks. That building also features dark brickwork but pairs it with copper-red metal for a tonal juxtaposition. I wonder if this dialogue appeared by coincidence or by design.

One way or another, D_Station feels multifaceted and sophisticated. This layered composition helps balance the building’s elongated mass while uniting its elements related to different periods. From the bridge, one can see a setback marking the location of an old powerline pylon. Here, a black metal wall and a corner window stand vis-à-vis with wood-colored slats. At the northern end, a sequence of diminishing volumes culminates in a wooden pergola over the plaza.

D_Station, 11.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

The site will likely gain additional nuances and details as the project progresses, but one thing near D_Station is certain: the sense of spatial intrigue will remain. It’s easy to say that the backlot of the Citadel business center and the former abandoned site have been given new life, but there’s more to it than that. One could also note the paradoxical placement of the building: its eastern façade aligns with fences enclosing two plazas and directly borders the railway’s edge, rendering it entirely inaccessible. Yet this same façade is highly visible from the bridge, adding an enigmatic quality to the building. In many ways, the depot remains tied to its railway origins. Yet D_Station’s new purpose – as hinted by its name, perhaps intentionally echoing the word “distance” – represents a departure from history. The building is now distanced, both figuratively and literally, as we observe it from afar, standing on the bridge.

It is equally fascinating to explore D_Station from the three pedestrian-accessible “urban” sides, where the ground level constantly shifts – sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically. The elevation change here is significant, about 5 meters from the Garden Ring to the railway. In the southern section, the building is surrounded by thin stone steps, slightly raised above the plaza and sidewalk. Moving northward, the path rises while the building sinks into a recessed area with a grassy slope. The northern plaza emerges at a one-and-a-half-story elevation. This interplay of levels makes the space unconventional. Its originality lies in the rises and falls, the changing perspectives, and the contrasts of impression. The recessed sections emphasize the building’s historical age, as if such “backlots” are where we instinctively look for something out of the ordinary. In this case, the difference is that it has been carefully landscaped and feels like a miniature yet natural extension of the art clusters around the Kursky Railway Station area.