Now the house is completed, and it can be examined in detail, as there are plenty of subtleties and intricacies here – and we can further discuss the stylistic specifics of the design concept.

“Little France” housing complex

Copyright: Photograph © Alisa Gil / provided by Liphart Architects

In terms of height and color, the house blends well with the street – in this case, it’s the 20th line of Vasilievsky Island. The house is beige, elongated, and not very tall – except perhaps for the courtyard behind the black grille that adds to the “palatial” character of the architectural solution, which is not so active around it. The surroundings, however, are diverse: the transition from the Mining Institute designed by Voronikhin and the modern “Officer Houses” to eclecticism, Art Nouveau, and Stalinist buildings here happens quickly, almost instantly; buildings of different times are mixed, as well as the yellow-beige shade mixed with terracotta-orange. Meanwhile, the difference from Moscow and other Russian cities lies in the fact that while styles may blend, the street’s structure is not disrupted, and Stalinist facades of the house standing right across the street (for example) can easily be mistaken for classical facades here; only in St. Petersburg can houses achieve such a level of mimicry.

Now, in this colorful company, an Art Deco house has appeared. In this case, it looks “museum-like” and decorative, almost “Egyptian”. Although the architect, Stepan Liphart, speaks of Leo von Klenze’s New Hermitage, personally, my first association was the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts designed by Roman Klein: there are also many acroteria on the facades there, and inside, there is the Egyptian hall beloved by many.

On the other hand, if we look at the déçu de porte’s, we’ll see that the relief is intricate, meticulously detailed in volume, and the glass-fiber-reinforced concrete here has veins resembling marble; generally speaking, these compositions should be understood as a kind of “keys” to the entire concept. And thus, the “radiance” of the ornaments on the house facades comes not from the sun of Amun Ra, whom the pharaoh Akhenaten worshiped, but from the paintings of the “dawn of a new world” of the 1920s – 1930s: here are both celestial bodies and retro-“technology” wheels, and corner elements.

In the upper frieze, the same motif is repeated abstractly: these can be arches with spokes or orange slices, but more likely just waves and abstract lines.

Shifting our focus to the filling of the partitions, we understand that here it’s not lotuses that we are seeing, but the same rays.

Meanwhile, the association with Amenhotep IV refuses to let go – in fairness, it must be said that his reforms, though they occurred three thousand years ago, developed the same theme as the dreams of the 1920s and 1930s about the sun of a new life. In short, the effect of stylistic syncretism, hypothetically imagined during some late Asiatic Hellenism of the Roman Empire era, is here projected into the geometric pattern of Art Deco, distributed quite generously across the facades.

The pattern resembles dresses: both Art Nouveau and the 1930s, with their endless lace nets.

For example, the rhomboid relief weaving of the black basement tier seems metallic, echoing the grilles of “French windows”: there the lace is transparent, and here it is of the relief kind. Such nets were popular in the costumes of both the 1910s and the 1930s, especially in headwear; sometimes they covered the entire dress.

The combination of black and beige cladding is also quite characteristic for both houses of the 1930s and modern houses inspired by them. The black basement covers the entire lower tier, reaches the gate columns, and ensures the integrity of the street line. In this case, its distinction, again, is expressed through the ornament.

On the other hand, we can see a subtle rustication on the main entrances, which rhymes nicely with the dentils, both larger and smaller, and with those same key “radiant” inserts above the doors.

The facades are mainly finished with glass-fiber-reinforced concrete, but the architects were able to make the relief quite prominent. Moreover, the panels have been adjusted to the pattern: the seams are not horizontal, and the ornamentation comes together in a puzzle-like fashion.

And it’s not just about the ornamentation – the ornamentation is merely a complement to the recessed projections, which form a rather complex, layered rhythm here. Ultimately, they transform the walls into a grid with a predominance of almost Gothic vertical elements.

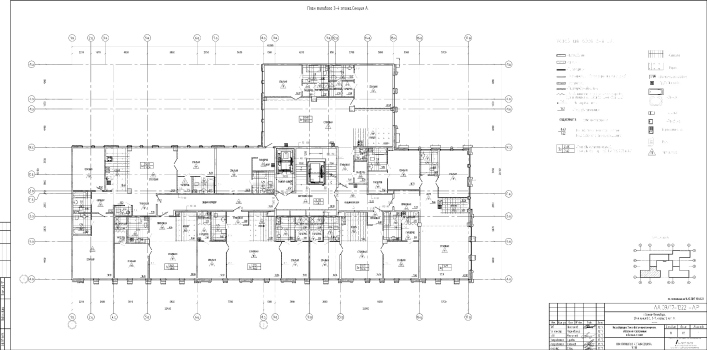

“Little France” housing complex

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Naroditsky / provided by Liphart Architects

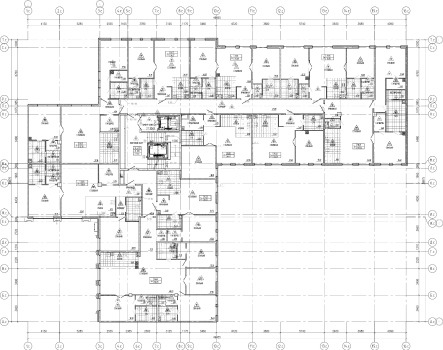

However, the stratification is not limited to the façade level – the house itself (and this is especially noticeable from the courtyard), is assembled from façade “layers” stacked on top of each other. These are echoed by the terraces on the roofs, the latticed balconies of the street entrances into the integrated two-story apartments – “city houses”. The house is intricately composed; it includes a series of unconventional planning and volumetric solutions, although at first glance, they may not be immediately apparent.

What catches the eye is how the house confidently maintains the red line.

And undoubtedly, the courtyard – it appeals to the rental houses of early-20-century St. Petersburg and at the same time resonates with modern solutions with the same references; to some extent, such a courtyard facing the street but separated from it by a grille (you can look, but not everyone can enter) – has become one of the characteristic features of modern St. Petersburg.

Nevertheless, the house is different from all the others. For some reason, it was called “Little France”. In France, too, a lot of different houses can be found, but the proposed solution seems to me much more British. This is indicated by its decorativeness, the flat pattern of the partitions, but especially the vertical details above the cornice, resembling pinnacles and ornamented pipes, which are so common in English castles of the 16th – 17th centuries. And, above all, the miniature clock tower on the axis of the courtyard. They all remind one of the style that developed in Britain during the Jacobean period, then enthusiastically embraced in North America, where architects successfully carried it through to the Art Deco era and beyond.

Make sure to notice the intertwining pattern on the tower. This pattern no longer resembles Egypt; it is quite Gothic, although if you break it down into elements, you will most likely get the same conventional lotus.

And about the triangles of the frieze in the central part? The flaming Gothic sends its regards here. And in this specific case, I will say that such a motif could have existed in the 15th and 16th centuries in both France and England.

“Little France” housing complex

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Naroditsky / provided by Liphart Architects

“Little France” housing complex

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Naroditsky / provided by Liphart Architects

One of the peculiarities of architecture during the Jacobean period is its ability to absorb and digest almost anything: Italian Renaissance, Gothic, even neo-Greek, or Egyptian. Another peculiar feature lies in its somewhat restrained respectability.

If we were to mention that Russian ornamental motifs and pseudo-Russian style of the 19th century are distant relatives of this phenomenon, we would confuse everyone and would have to indulge in a really long explanation indeed. So, let’s abandon stylistic speculations and limit ourselves to a simple observation: besides everything else, the house finds parallels in Stalinist architecture, which, as is known, was interested in both Art Deco and various examples of European Renaissance. And this parallel is very recognizable: the facades are made rhythmic by decorative compositions with pediments, one of the favorite techniques of “Stalinist” architectural compositions, and it successfully integrates the house into the surrounding context. Thus, the house ends up being both native and foreign on St. Petersburg’s Vasilievsky Island.

Regarding the fact that the house here is “foreign” I will probably need to make one more remark here. Art Deco is very popular now just because it allows the architects, on the one hand, to integrate a new house into the historical context, while emphasizing its novelty, and on the other hand, to respond to the demand of apartment buyers by offering them a house that looks like a palace. This trend has a certain internal paradox because, historically, Art Deco was known to be a style of public buildings, theaters, shops, and banks, and was less common in residential houses. As for the Russian, or, to be more precise, Soviet, 1930s, it is now known that there was a variety of Art Deco in Russia, but it did not resemble either the European or, even less so, the American Art Deco style.

So now, the facades of new clubhouses that are appearing in the central part of Russia’s major cities seem to repair both historical injustices.

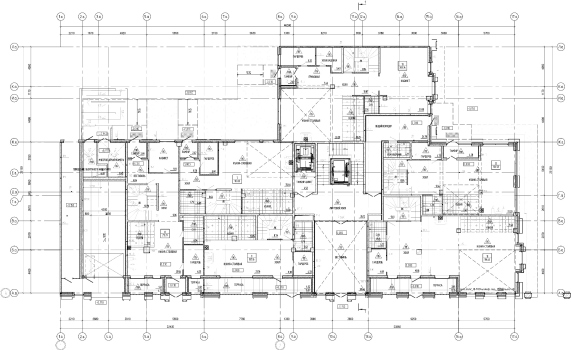

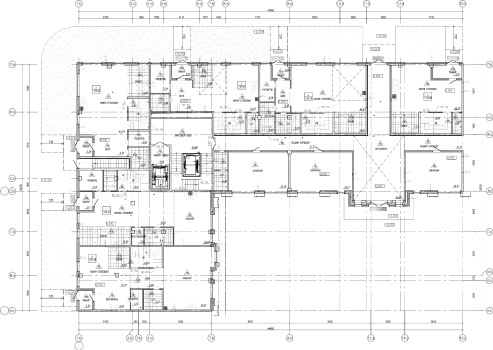

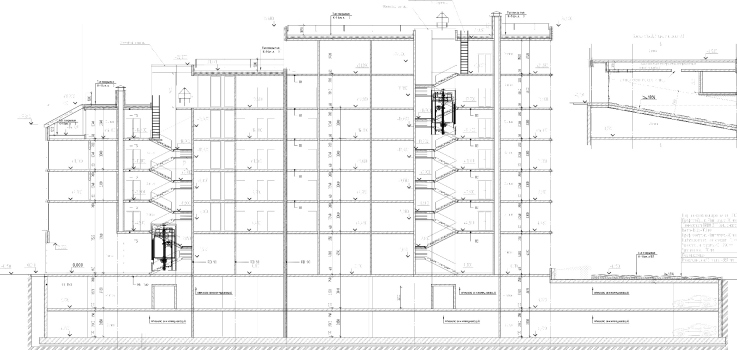

Plans and sections: