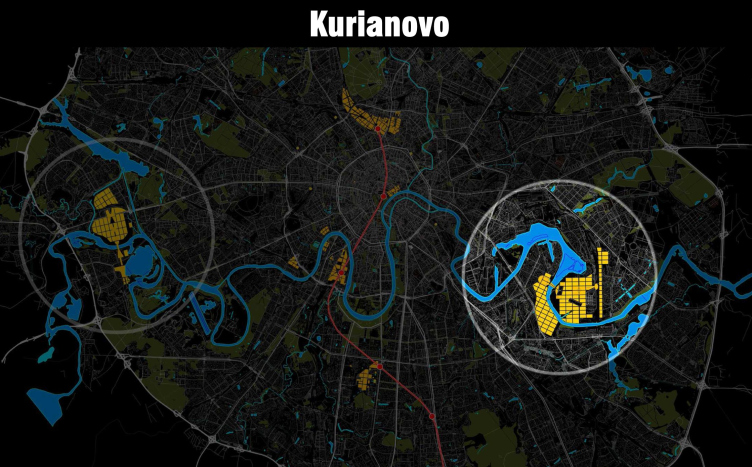

We will remind you here that in July 2011 it was announced that the territory of Moscow would be expanded by 2.5 times westward. The competition, dedicated to the search for ideas for developing the Moscow agglomeration, was organized by the Genplan Institute of Moscow at the governmental commission in 2012, after the city was expanded. Many of its participants, however, preferred to regard the potential of the metropolitan agglomeration as a whole and even voiced their opinions in favor of “symmetrical” development of the megalopolis in the future. Today the contest is 10 years old, it belongs to history, which makes it all the more interesting. We met with the deputy director of the Genplan Institute of Moscow Alexander Kolontai, who was in charge of organizing the “Big Moscow” competition, and probably knows more than anyone else about it.

Alexander Kolontai,

deputy director and the leader of the General Design Department of the Genplan Institute of Moscow.

Most likely, to celebrate the 10th anniversary of New Moscow, they will give it a lot of press coverage: about what was built, and how, what challenges were there, how they were overcome, and about other professional and rather boring things. I, however, can share about the main event that preceded the appearance of New Moscow – about the organization of the international competition. About its backstory, how it went on, how it ended, and about the conclusions that we were eventually able to draw.

The Backstory

What events preceded the competition?

In 2010, in the form of the new master plan, Moscow received the development strategy up until 2015, which proved that sustainable development was possible within the original borders.

However, already a year later the new government of Moscow and the president of Russia did not agree with that. In 2011, Moscow expanded, or, to be more precise, grew by half, when Dmitry Medvedev at St. Petersburg Economic Forum announced that a new metropolitan federal district was to be instituted.

Not everyone realized the consequences of this. Is a new administrative/territorial unit being created? Are they changing the borders of the Central Federal District? Are they planning on gradual formation of a federal administration responsible for the integrated development of the Moscow agglomeration with the participation of the Moscow City and regional governments?

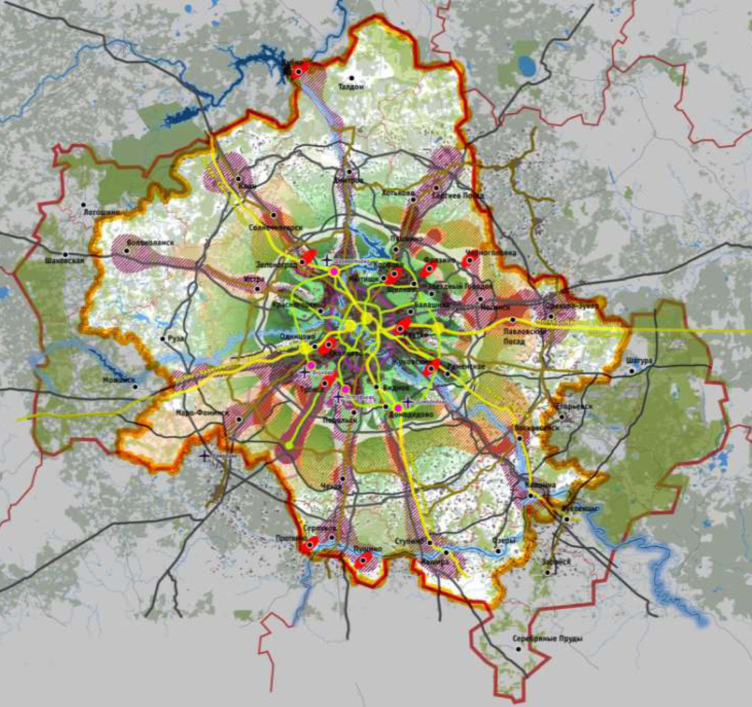

In September 2011, the Government of Moscow issued a decree about developing a concept of Moscow agglomeration, which mentioned a competition that was to be organized by the Genplan Institute of Moscow in order to answer questions about the future of the annexed territories, the master plan 2010, and the “Metropolitan Federal District”. Thus, we were finally able to get down to preparing a document for the territory, about which we had long since thought, and at what we had long since looked, when we worked on the master plans 1999 and 2010, when we studied the experience of planning and management of the Berlin, London, and Paris agglomerations.

Let me remind you that in the post-Soviet period, a huge number of migrants came to Moscow and the Moscow region. Only 60% of the jobs here were occupied by Muscovites, and the remaining 40% were visitors from the region and other regions. Of course, this meant more cars, there was also “pendulum” migration taking place, and Moscow was bursting at the seams. All of these things – the migration flow, the transport situation, and trends for building “second” housing, as well as some of the Muscovites moving to suburbs – left the town planners wondering what to do with it.

How come the master plan 2010 did not address these issues?

The master plan that was adopted in 2010 was not just rational – it was positioned as a “plan of necessities” that was setting the vector for every part of the city, and not just the ones that were commercially promising, as was the case with the previous “plan of opportunities”. The master plan 2010 was essentially an attempt to give scientific rationale for the conditions, in which it would be possible to reduce the transport tension and achieve a reasonable balance between the new housing construction and the changing structure of the city economy.

For example, according to this document, the strategic priorities for the new construction were laid not on the city’s periphery, but on the land lying between the third and the perspective fourth transport rings, where, thanks to removing the old production facilities and the integration of the minor railway ring into the city transportation system, the future Moscow would be formed. The transport construction plans included opening the big metro ring by 2025, developing railway diameters, the north and the south strings, and even futuristic construction of new highways running above railroads.

However, if today all these projects have been or are being implemented, solving the problems of the “old” Moscow, then why did they need the “new” Moscow? What was it in the master plan strategy that the leadership of the city disagreed with at the moment? Possibly, it was the strategy of reserved housing construction in a volume of 95 M cubic meters instead of the “inertial” 110 M by 2025, as well as 20 M cubic meters of the to-be-demolished stock of dilapidated housing, to which the master plan 2010 referred certain series of five-story, nine-story and even 12-story houses. This would imply displacing up to 1.7 M Muscovites from this housing stock. At that time, there was neither a legal framework nor an effective urban planning experience for developers to implement such a strategy. Active new construction on vacant land, without having to tear down the old housing stock, seemed to make sense. The Moscow Renovation Program was hard to imagine back then.

Moreover, the new city leaders, making a statement about Moscow being a global city and an international financial center, posed new questions. For example, why not take a more open-minded look at Moscow, including its agglomeration, and use the annexed lands of the New Moscow to accommodate the new federal administrative center and to remove a significant part of federal projects from Moscow’s historical center? And this became the task of the contest for the concept of developing Moscow agglomeration.

Did the town planners have any points of reference for answering these questions?

Of course, we did. In 2008, Paris organized a big competition called “Big Paris” that we totally kept track of, and examined the results. And at that point in time we did not know that we were in for similar work. Nonetheless, we learned a lot, and it was then that we developed an archive of the projects and a desire to look at Moscow as a large international center.

We also considered the experience of Big London or the single agglomeration of Berlin/Brandenburg. To study the experience of forming a new administrative center, we organized a business trip to Putrajaya – the new capital of Malaysia as the innovative satellite city of Kuala-Lumpur, and the embodiment of the environmental ideas by the architect Walter Griffin – the new Australian capital Canberra.

Organization. Stages. Success.

Alright, the Genplan Institute was commissioned to organize a similar competition in Moscow…

In December 2011, we announced the start of the competition. The expert team consisted of 41 members, including representatives of the working group under the President of the Russian Federation, members of the Coordinating Council of Moscow and the Moscow Region, the Union of Architects of Russia, the Academy of Architecture, specialists of our Institute and our international colleagues who worked in the Planning Departments of European cities.

According to the conditions of the competition, eligible were consortiums that included specialists of various areas of expertise and various competences, but having a Russian company within the group was a stipulation. To our surprise, this contest aroused a lot of interest in the world. We received 67 applications, including 37 from international teams. Representatives from 21 countries took part in the competition for the development of Big Moscow. Eventually, 10 teams were shortlisted. Four of them were led by Russian companies, and the other six by foreign ones: these were two French teams, an Italian one, Spanish, British/American, and Russian/Japanese.

What tasks were posed before the participants?

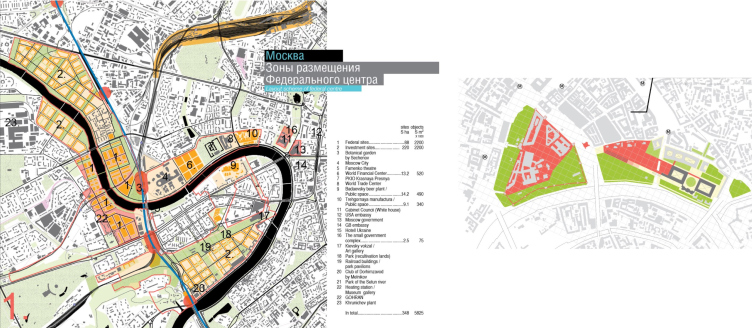

It was decided that the competition would include three nominations: best solution for the concept of development of Moscow agglomeration, for the development of Big Moscow, and for forming the new federal center. These were also three stages of the competition and three projects that each of the contestants was to prepare. Each of these projects was evaluated individually, i.e. each of the teams could potentially win in all the three nominations, in two, or in just one.

Each project stage included organization of two monthly seminars and six seminars over the entire contest period. At the seminars, the contestants made reports about their progress, and the experts evaluated the reports, me the moderator. The competition had two official languages, Russian and English, and all the reports were drawn in two languages.

At the first stage, within the framework of the first seminar, the contestants were to answer the question: can Moscow be a global city, what things does it miss to become a large international center, and what basic solutions do they propose for all the three projects – for agglomeration, New Moscow, and for Federal Center?

Ideas

How did the contestants answer these questions?

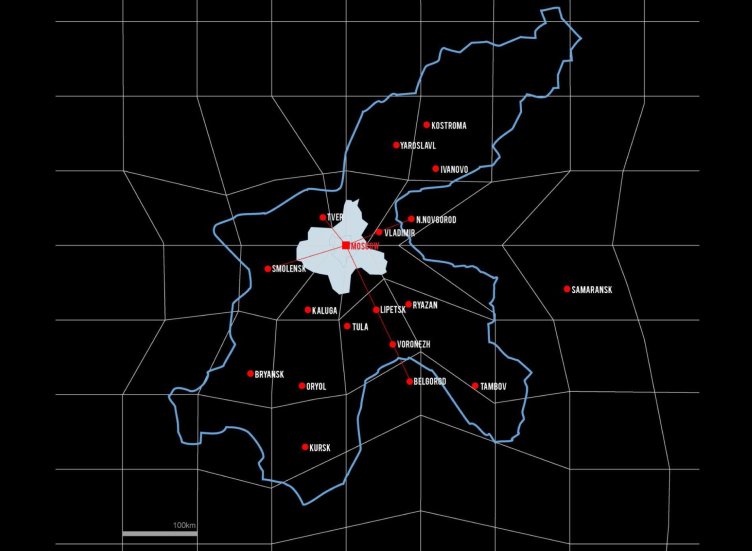

The OMA team led by the famous Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, proceeding from the experience of regional cooperation within the Netherlands, stated: we need to unite Moscow and the Moscow Oblast.

First, the administrative solution had to come, then everything else was to follow: solving the technical issues of the infrastructure, appearance of four mega-cities around Moscow as the main structural elements, and so on. However, Moscow will become a global city through the administrative annexation of the Moscow region.

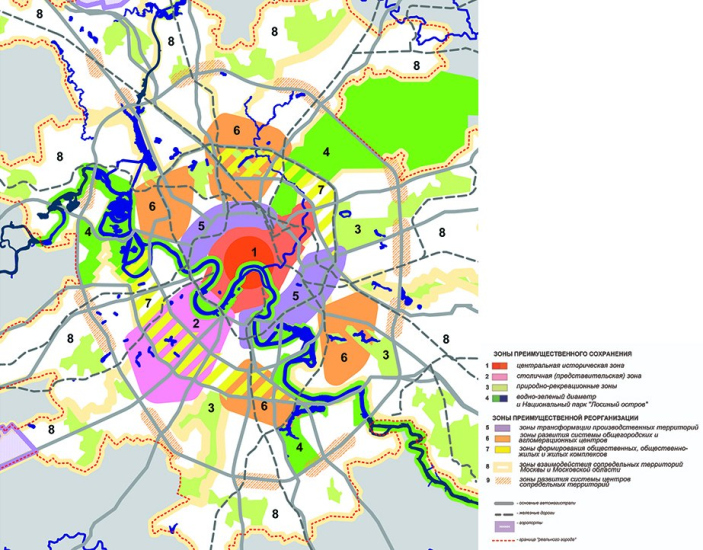

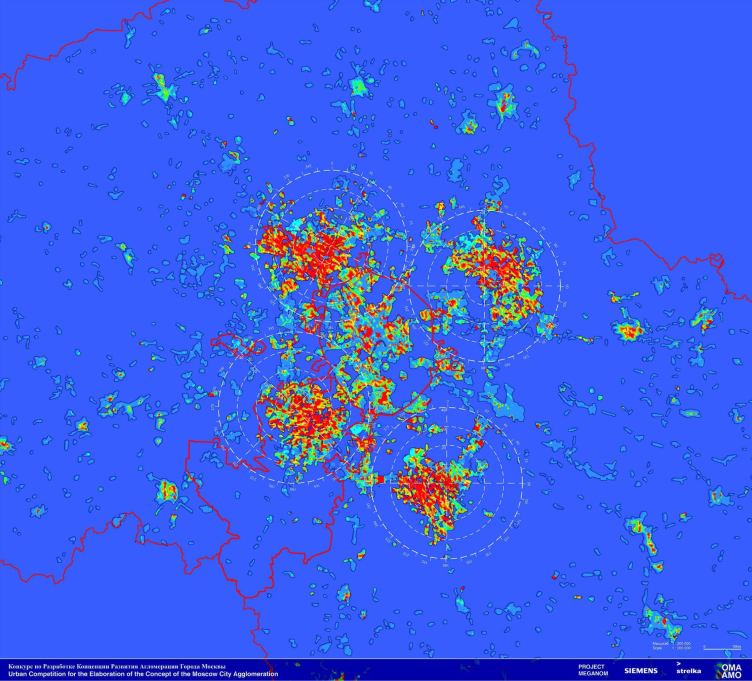

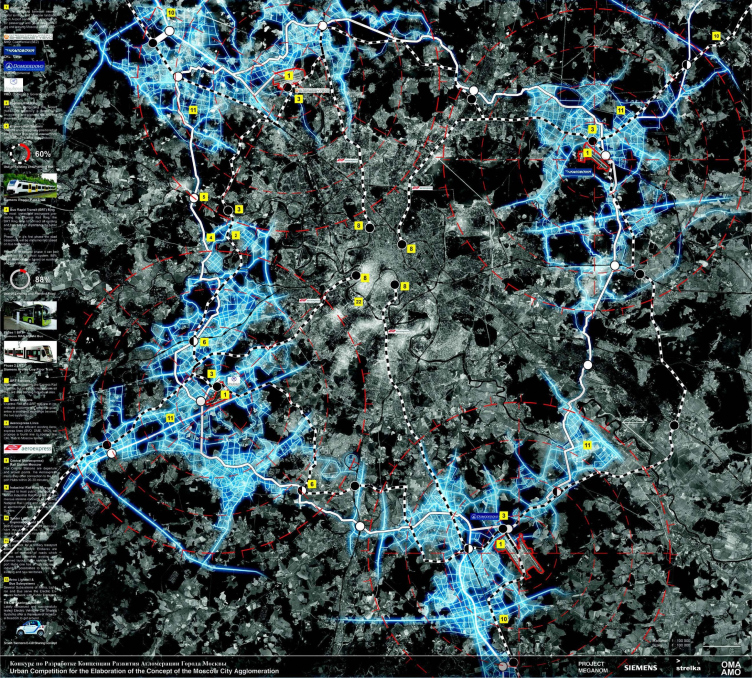

The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright © OMA Consortium

The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright © OMA Consortium

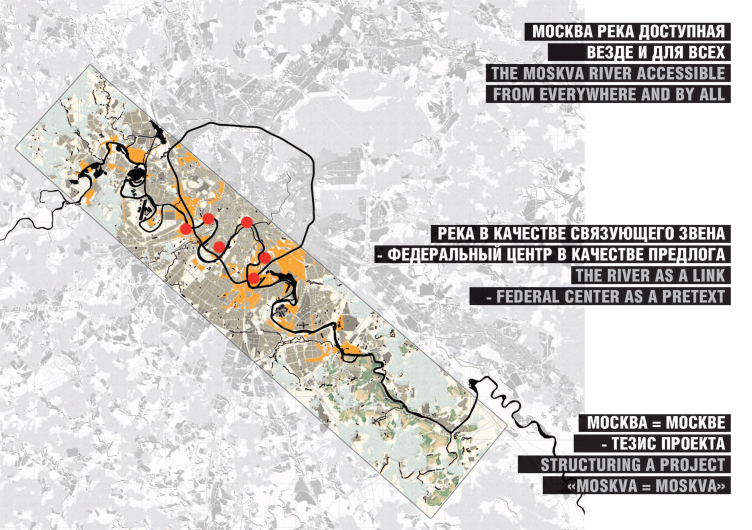

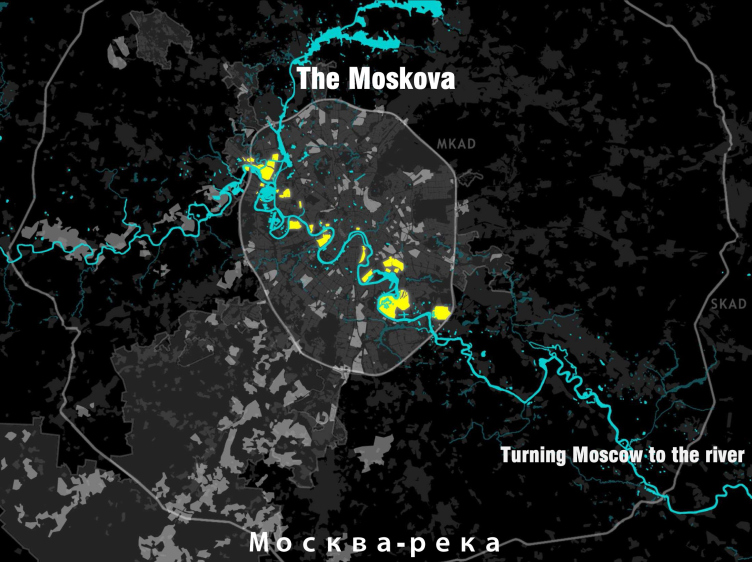

The solution based upon developing the agglomeration in all directions was also proposed by the Russian/French consortium of Ostozhenka and Ateliers Lion Associés. According to them, annexing the adjacent territories was only a matter of time. This team defined the New Moscow as a system of eight sectors surrounding the city, proposing to keep the governmental functions in the center, and paying more attention to the Moskva River and developing its banks.

The River and the old town. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Ostozhenka and Ateliers Lion Associés

On the left: a proposal for the development of administrative and business functions in the City area; on the right, a proposal for the placement of a federal government agency in Zaryadye. The River and the old town. The concept of the “Big Moscow&#

Copyright: © consortium Ostozhenka and Ateliers Lion Associés

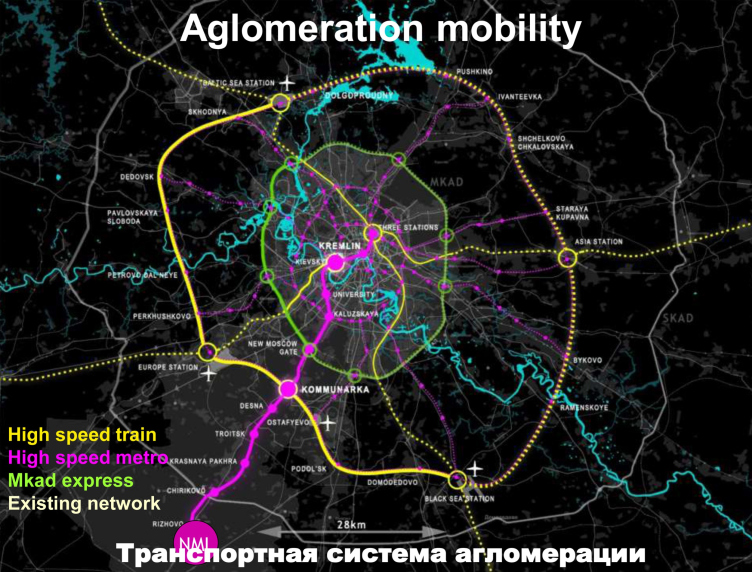

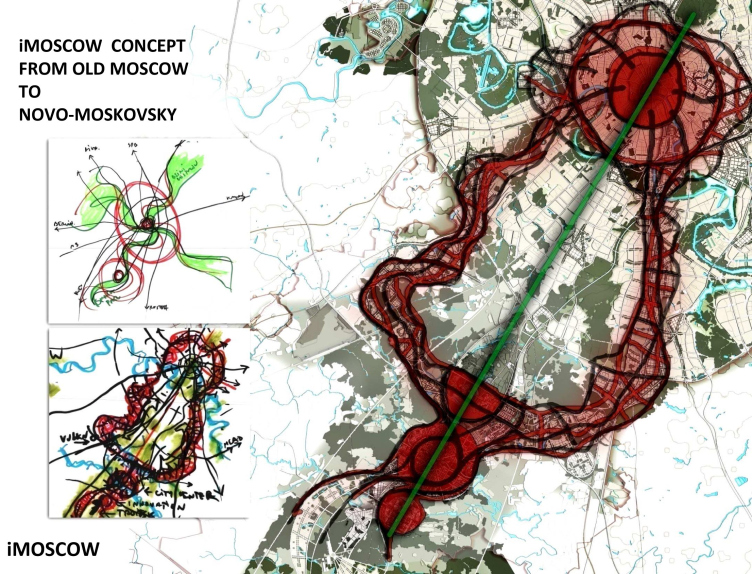

The French/Russian team ANTOINE GRUMBACH & ASSOCIES Sarl, which back in the day took part in the Parisian competition, continued to develop its idea of “Big Paris”, i.e. the idea of a super city consisting of three cities. They were saying: “You want to make Moscow global? Look at St. Petersburg, look at Moscow, look at Sochi – this is the line of urban development. In the former case, you have an exit to the northern seas, in the latter – to the southern ones. Development in these two directions is very important.”

The concept of the planning organization of the Moscow agglomeration. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © Antoine Grumbach et Associés, Paris, France

The concept of development of the transport infrastructure of the Moscow agglomeration. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © Antoine Grumbach et Associés, Paris, France

The idea of linear and ray-based development of the Moscow agglomeration in the new annexed territories, which can also be duplicated in the northwest (St. Petersburg) or eastern (Nizhny Novgorod) directions, was pronounced to be the best in this competition.

The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Grumbach – Wilmotte

The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Grumbach – Wilmotte

The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Grumbach – Wilmotte

The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Grumbach – Wilmotte

The American team Urban Design Associates Ltd also was not alien to the idea of uniting Moscow and St. Petersburg. They saw in it a huge intellectual and economic potential for the development, emphasizing that this axis was particularly important for the future of Moscow. This, probably, was the most feasible solution also due to the fact that America has a huge experience in managing agglomerations. Thus, they proposed to apply similar ideas to our capital city.

The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Urban Design Associates

Proposal for the development of the nearest belt of New Moscow

Copyright: © Urban Design Associates, Pittsburgh, USA

The center of New Moscow in Kommunarka. Design solution

Copyright: © Urban Design Associates, Pittsburgh, USA

Four compact cities, united by canals, in a communal apartment. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Urban Design Associates

Sketch of the center of New Moscow in Kommunarka. Design solution

Copyright: © Urban Design Associates, Pittsburgh, USA

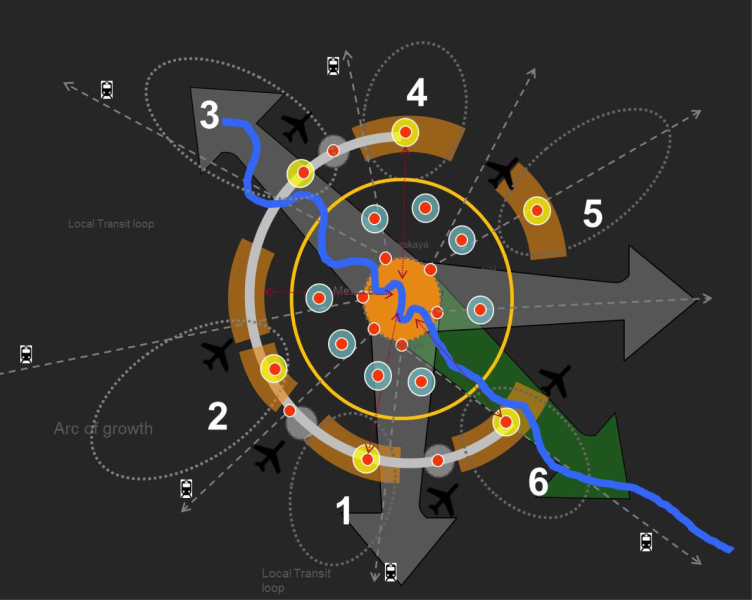

The idea of the Russian/Japanese team was expectedly based upon the experience of Tokyo – a city that has had major success in the development of its public transportation system. The poly-centric concept, similar to Tokyo’s concept development, where four new cities were formed on the periphery, was to be recreated for Moscow.

Model of the nearest Agglomeration belt. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Central Research and Design Institute of Residential and Public Buildings, РААСН, Nikken Sekkei, and others

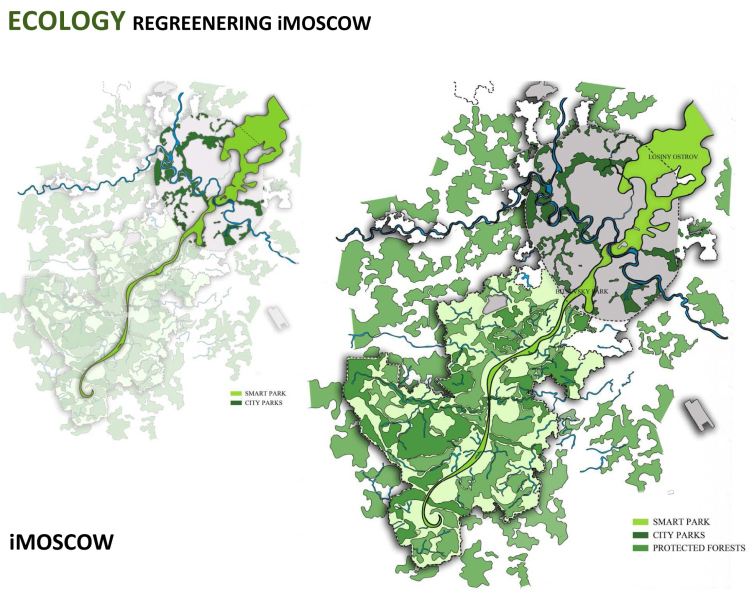

The Spanish team, led by the well-known architect Ricardo Bofill, were planning to lean on the experience of Barcelona and Madrid. They proposed an integrated green organization of Moscow, with a special emphasis on environmental protection.

According to Bofill’s team, Moscow was to be turned into a “garden” city with large green squares, which, like rays, would stream in all directions.

The green framework. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Ricardo Bofill architecture

The ratio of the “old” and “new” Moscow. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium Ricardo Bofill architecture

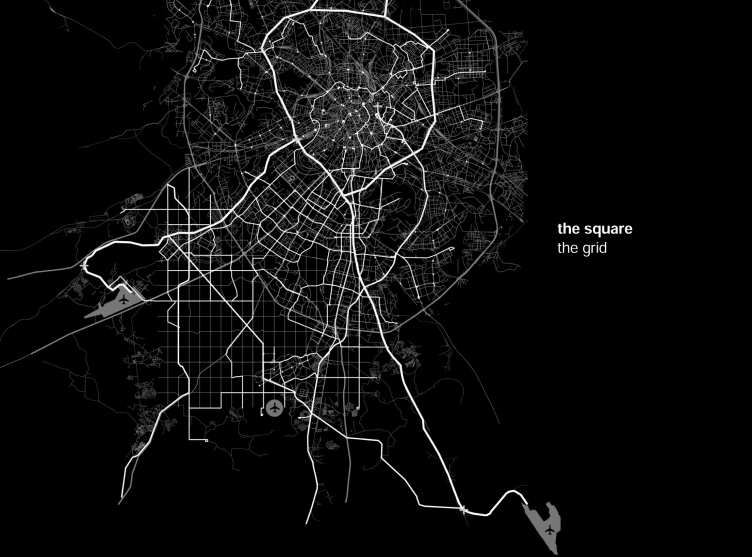

I also cannot help mentioning the idea proposed by the Italian team, which also took part in the Parisian competition and did the project of the Brussels agglomeration. The Italians believed that solving the agglomeration and transportation problems of Moscow would be achieved through mutual penetration of a transparent street network and a system of shortcut highways built in order to break away from the monocentric city plan.

The orthogonal grid in the southwest part of the city. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium STUDIO 012 / Bernardo Secchi, Paola Viganò

TThe new spatial structure. The concept of the “Big Moscow” competition, 2012

Copyright: © consortium STUDIO 012 / Bernardo Secchi, Paola Viganò

What were the first results?

The first seminar demonstrated that, first of all, everybody sees the potential of Moscow as a global city, and second, which is just as important, all the international participants showed respect for Russia and the Russian experts.

This was the time when we were friends with the whole world, and everyone treated us as peers and was ready to work with us. Despite the fact that there were arguments and even conflicts during the competition, we spoke the same professional language and looked to understand one another.

The Challenges

What challenges were you confronted with during the competition?

The challenges were both organizational and conceptual. The organizational challenges included: problems of different mindsets and different experiences that the teams had. As for the conceptual problem that arose during the creation of the concept of Big Moscow, it lay in the fact that 80% of the annexed territories were nature – agriculture, country homes, the restricted area around Vnukovo airport, and protection zones around rivers. After the foreign teams studied the territories that they were about to work with, they saw that it was not that easy to transfer them into the status of a full-fledged city with an environment as compelling as that of the “old” Moscow. The reality – with the main “symbol” of the Moscow region, i.e. a gray concrete fence encircling industrial parks, as well as sprawling dacha settlements – was very different from the photographs that they used to see in the tourist brochures.

There were also difficulties that arose during the development of the agglomeration. All the members of the competition realized that there was no point in trying to create an agglomeration if you don’t have tools for managing it. And the main problem for the Moscow agglomeration was specifically the problem of management. And, since we could not tell the contestants how the Moscow or the Russian government envisaged these management tools, each of the teams simply saw what they could dream up, based on their own experience.

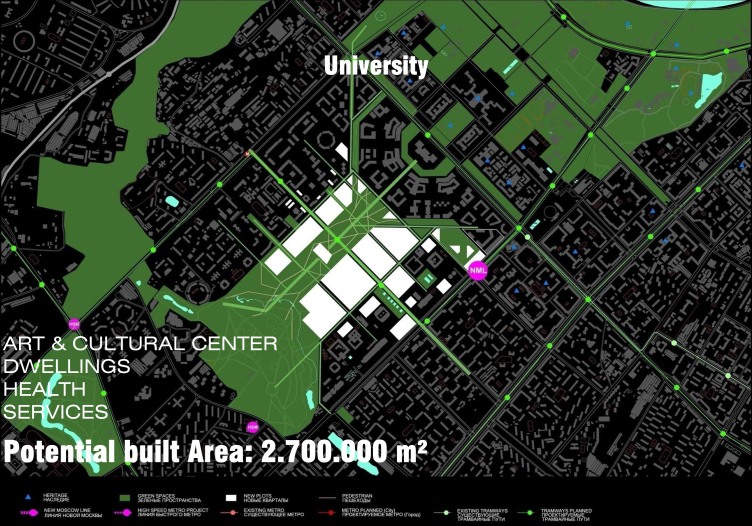

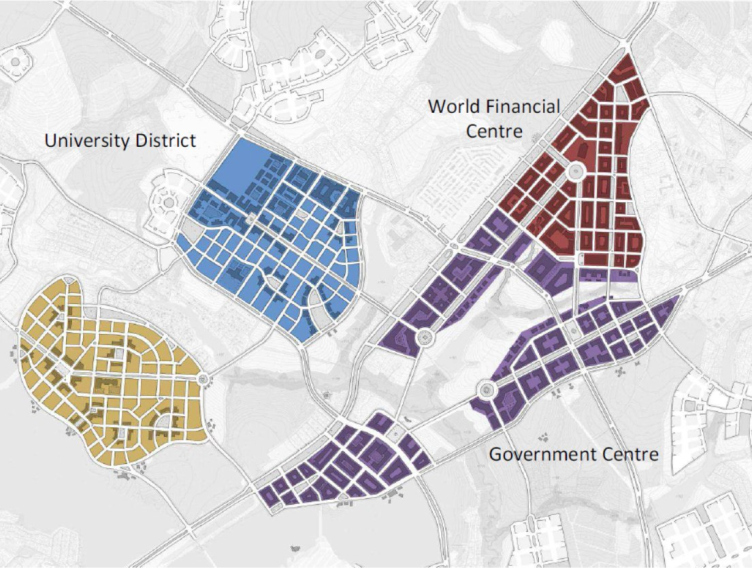

The problem with developing the concept of the federal center was that we did not know whether or not the program of moving the federal government bodies to those locations would really be implemented. We kept saying that we would build a center in New Moscow that will become the main point of growth, fostering the attraction of investment and development of infrastructure, but there was no official document confirming that statement. Therefore, we simply worked on that project, hoping that it would be implemented one day, and our work would not be in vain.

What were these hopes based upon?

We had the quite real experience of Putrajaya, the new capital of Malaysia, before our eyes. During our trip that we took before the competition we had a meeting with the government of Malaysia, and looked at how beautifully the new capital was organized, how the buildings and the landscape looked, we saw the superb-quality architecture, and we were simply stunned. Of course, we believed that these developments could be applied in Russia.

By the way, the American team, which got the prize for the concept of the new federal center, was probably inspired by the administrative capital of Malaysia as well. They came up with a very beautiful landscape, and they thought of every planning factor for creating a federal center in Kommunarka.

Considering the above, can you say that the contestants were responsible about their work?

Their work at the competition was evaluated by experts – each report, each presentation made at the seminars. Only after they had passed to the next stage, the contestants received their “paychecks”. In addition, based upon the results of each seminar, I made publications, analyzing the presented projects, thus encouraging the contestants to perform as deep and as thorough work as possible. They were aware that the results of their work were totally available online at every stage. This was a very strong motivator because everyone wanted to show their performance to the best advantage.

Yes, each of the tasks did generate questions, and tension was mounting from seminar to seminar. We as the organizers wanted the contestants to do real projects and come up with feasible solutions, not get carried away and do some sci-fi things – the government was expecting concrete solutions. Once all the teams realized that, there was a real breakthrough, and everybody got involved in the work for real. Furthermore, in the course of the work the contestants kept coming up with new proposals not only for New Moscow but for “old” too, which was really beneficial for us.

The Results

What were the results of the competition?

The best project solution for the development of Moscow agglomeration and Big Moscow were pronounced to be the developments by the French/Russian team of ANTOINE GRUMBACH & ASSOCIES Sarl. The best project of forming a new federal center was submitted by the American Urban Design Associates Ltd, but a month after the results of the competition were announced we found out that the relocation of the federal center was canceled. However, the main result of the competition was the fact that today many of the contestants’ proposals for developing Moscow in its old boundaries are being implemented. Working on the New Moscow project, the teams proved all the importance of the “old” Moscow, stating that we would not solve the problems of the old capital at the expense of annexing new territories. What we needed was mutually beneficial programs for the development of both.

What changes in the city did the competition launch?

The capital, one way or another, used the ideas of the architectural teams of the international competition 2012. Upon the completion of the competition, we, together with Moskomarkhitektura, got down to working out a new master plan with consideration for the annexed territories. This document, developed under general guidance from the chairman of Moskomarkhitektura, Julianna Knyazhevskaya, and agreed in 2017, became a more flexible one, compared to its predecessor, to a large extent due to the large scale of the territory and the sheer fact that it included a lot of competition ideas – both on the annexed territories and the old Moscow.

On the other hand, the project solutions, proposed by the contestants, proved the validity of the solutions proposed in the master plan 2010 – about the necessity of reconstructing the industrial zones lying in the middle part of the city, around the minor railway ring, and along the Moskva River, as well as the reconstruction of the dilapidated housing stock. The architects vividly demonstrated ways to explore the potential of these territories. A number of their proposals were reflected in the new master plan 2017, while all the territories of New Moscow, designed for construction, were gradually covered with predominantly housing projects.

In that same year of 2017, they adopted the 373 Federal Law about Integrated Development of the Territories. The “old” Moscow saw active housing construction again. The era of renovating Moscow’s housing stock began – something, about which the American team spoke during the competition, proposing six strategies for reconstructing and developing the housing stock in order to create a high-quality urban environment worthy of a modern megalopolis.

The international competition 2012 became the start of the new town-planning policy, didn’t it?

Yes, it did. To a large extent, thanks to the contestants’ proposals, particular importance was attached to themes that seem quite habitual now: landscaping and park construction, development of public spaces, landscaping of urban areas, and reconstruction and modernization of the housing stock.

All the contestants spoke about the necessity of developing the public transportation system, which also became a further impetus for the development of the Moscow metro and the Moscow central diameter. The teams also spoke about the need for further deterrence of using private vehicles, making the parking chargeable. These ideas were heard by the city government. And today we are seeing fewer cars downtown, lots of city people have switched to public transportation, and the environmental conditions in the city center have significantly improved.

A special form of Moscow’s new town planning policy is the organization of international competitions. The competition 2012 took place 80 years after the first town planning competition organized in Moscow. After that, international competition started to be held in Moscow on an almost annual basis: 2013 – Zaryadye Park, 2014 – the embankments of the Moskva River, 2015 – Skolkovo Technology Park, 2017 – competition for renovation of residential areas, 2018 – a concept for Rublevo-Arkhangelskoe, and so on. Many of these competitions were organized by our Genplan Institute of Moscow.

And what did the Russian architect learn in the course of this competition?

An important skill that our architects developed in the course of the competition 2012, was the ability to make really high-quality and exciting presentations. Our international colleagues showed us that a boring presentation can be turned into an exciting video. They learned that you can share in an exciting way what tasks you have to solve, how you can sharpen people’s focus on the city problem in a creative way, how to convince everyone of the effectiveness of your solution, how to show what changes it will bring, and what the outcome will be. Now we can do this, and this is important.

The Conclusions

What conclusions were drawn as a result of this competition?

Thanks to the competition held in 2012, we all realized that Moscow was to develop in accordance with the international standards. We realize the importance of being open-minded and being able to look at ourselves from aside, the importance of attracting international experts in the field of architecture. Sometimes, we just don’t realize what our weaknesses are, and this came up during the open discussions. Because you can only assess yourself objectively in a competitive struggle, when different opinions are taken into account, when your specialists do not just pound on one idea, but select the best of the available options.

Yet another conclusion that we drew from the competition was that until we draw up a document that will be legit for both Moscow and the Moscow region, all the conversations about developing an agglomeration will remain conversations. To make sure that the town-planning policy is in place, you first need to adjust the mechanics of managing this extremely interesting territorial project.

What can you say about this competition today, 10 years later?

Implementation of the contestants’ ideas is a really long-term program; this task is not for ten, but for 30 or even 40 years. When at our conferences we share about the projects of New Moscow, many experts ask: why did you only go southwest? We explain that this was our first attempt, an experiment. We planned to look at how Moscow would work in combination with this regional territory, and then spread this experience on other sectors, i.e. to the entire agglomeration. And then everyone agrees that this was the right move.

Of course, building a new city in the conditions and under the restrictions that are in place in New Moscow is extremely difficult. Making a compact and efficient urban formation out of a region with a network of populated places, such as New Moscow, requires very serious financial investment. But such is our country that cities do not arise here in the best possible places, but where they are needed.