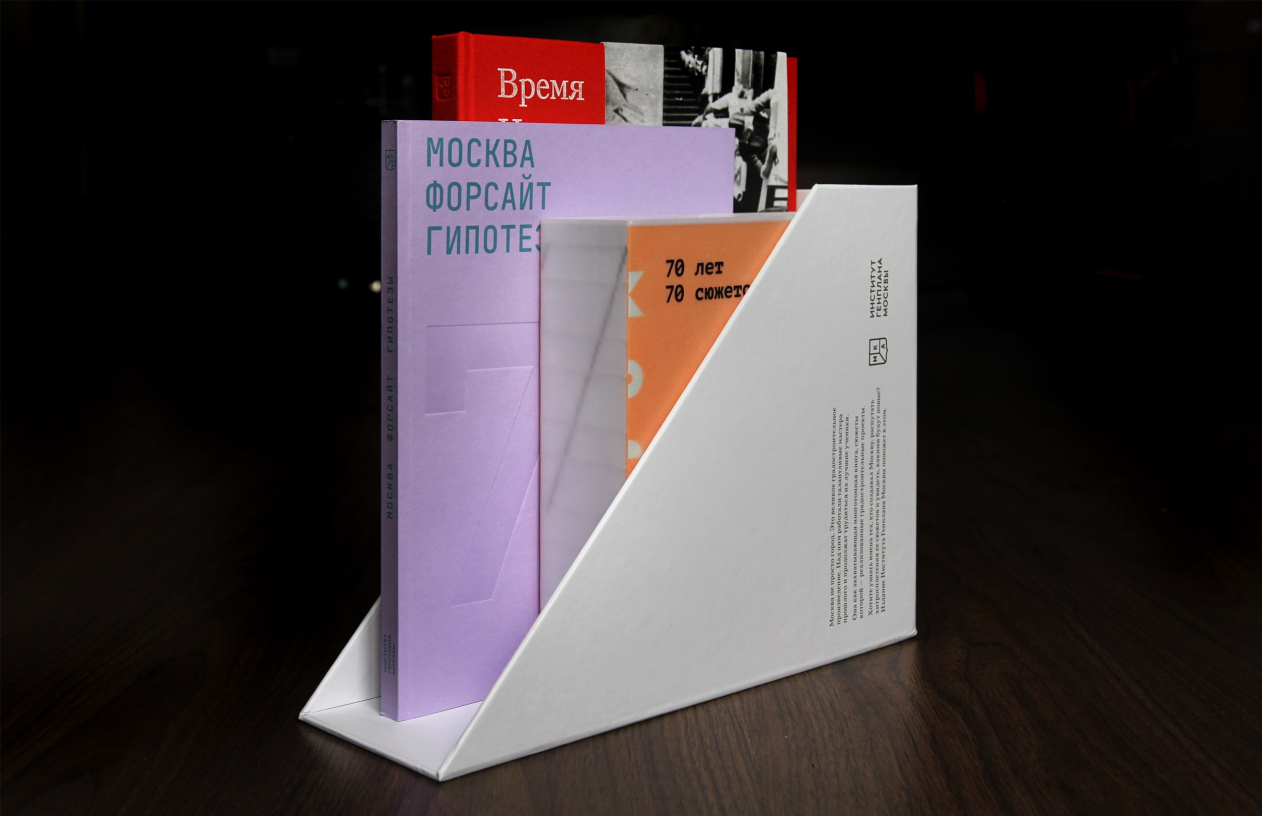

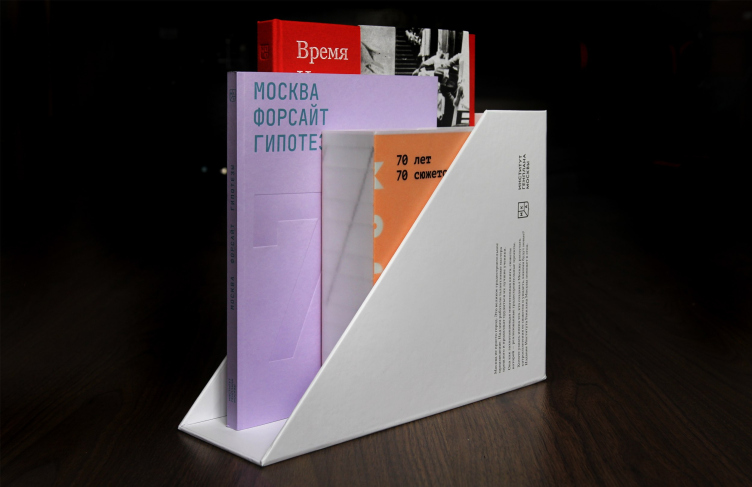

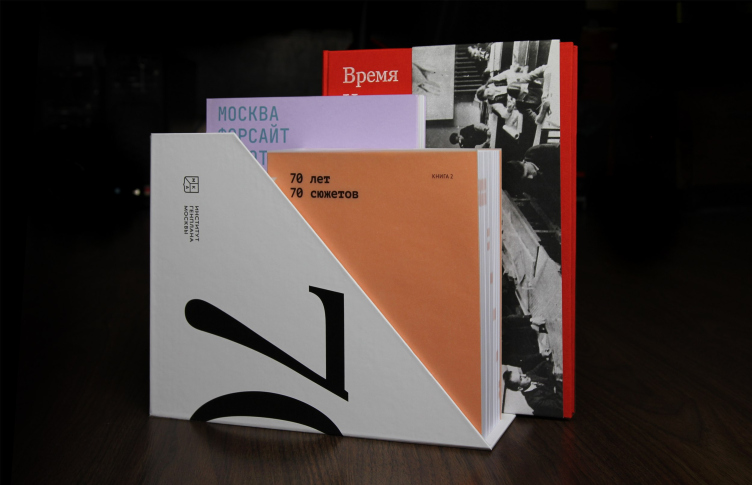

70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

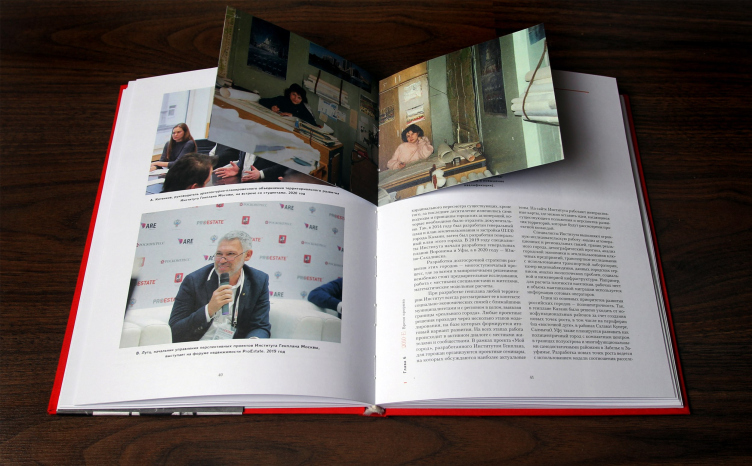

The authors of the third volume (first by numeration), entitled as Book 1, present the 70-year history of the Institute in three different ways: in the form of essays based on the chronology of decades; then on individual topics; and finally through the prism of the personal view of three directors of different times: Valentin Ivanov, Sergei Tkachenko and the current head of the Institute, Tatiana Guk.

Tatiana Guk, director of Genplan Institute of Moscow

First of all, I want to thank our founder, who did everything to keep the Institute alive – Architecture and Urban Planning Committee of Moscow – as well as its “predecessors” that formed the town planning policy in this city. The collaborative work of Genplan Institute of Moscow and the bodies of executive power is a great example of synergy when the architects and designers dream up what the city must look like, and the management team knows how to make these plans a reality.

<...>

Any of the Institute’s employees will tell you that designing the city and creating a comfortable urban environment is their life’s work. Each of us is proud to work here.

<...>

I can tell you one thing: I surely do not regret the changes that took place in Moscow over the last decade. Moscow 2010 was a “wild market” city, garish, pieced together from odds and ends, and eclectic in the worst sense of this word. Today’s Moscow is a smart city, which has a competent policy for its preservation, including the preservation of cultural heritage, and its integration into the life of Muscovites. I know that the city’s leadership has done a lot to show the capital in all its glory: to put the facades in order, organize pedestrian zones, turn old parks into spaces where people like to gather and spend time.

<...>

Any of the Institute’s employees will tell you that designing the city and creating a comfortable urban environment is their life’s work. Each of us is proud to work here.

<...>

I can tell you one thing: I surely do not regret the changes that took place in Moscow over the last decade. Moscow 2010 was a “wild market” city, garish, pieced together from odds and ends, and eclectic in the worst sense of this word. Today’s Moscow is a smart city, which has a competent policy for its preservation, including the preservation of cultural heritage, and its integration into the life of Muscovites. I know that the city’s leadership has done a lot to show the capital in all its glory: to put the facades in order, organize pedestrian zones, turn old parks into spaces where people like to gather and spend time.

70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

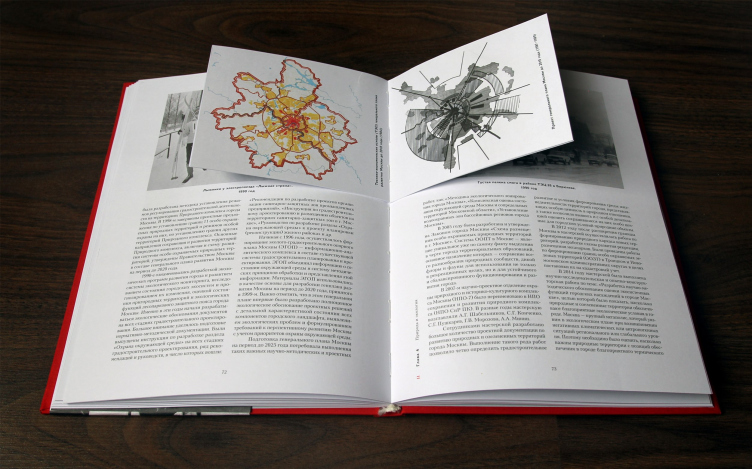

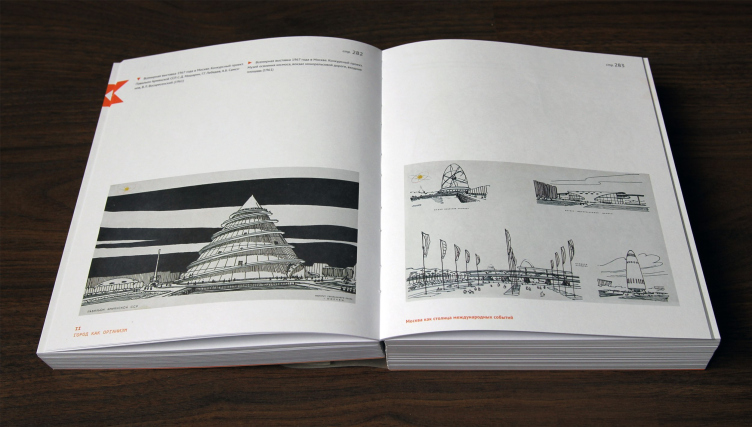

It would be the most logical to assume that the three anniversary books represent the past / present / and a look into the future. This is possible, particularly in view of the fact that the archive of the town planning projects developed by the Institute is part of the reality not just in the sense, in which any archive constitutes its “passive” part, but also because it is repeated in all the books: many of the things that were devised in the 1960’s or 1970’s are only being implemented now. The simplest and best-known examples are the construction of Moscow traverse metro lines or the development of the Moscow metro as a whole.

The project of a sports park in Nagatino, 1976. Book #2, Page 644. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Fragment. Photograph of the book page: Archi.ru

Another example that surprised me was the long story of the concepts for the children’s play park in Nagatinskaya Poima. Its place is now occupied by “Ostrov Mechty” (“Dream Island”). However, the first project of the play and sports park – shares Valentin Ivanov, director of the Genplan Institute of Moscow in 1983-1988 – first appeared in 1977, while the park as such was provided for in the city’s master plan 1971, along with other numerous sports facilities.

“What we were dreaming of was nothing like what we have here today – says Valentin Ivanov, who, when the park was designed, served in the capacity of Studio #3 of the Genplan Institute of Moscow, which was commissioned with this project by Mikhail Posokhin Sr. back in 1976 – And here is what we were dreaming of: one third of the land site was to be occupied by fields “for virtually every kind of sport you can think of”, another third was to be occupied a landscape park, and the ash dumps of the ZIL power station were to serve as a basis for the “Ancient Fortress” with traditional Russian amusement rides.” (Book 1, Page 98).

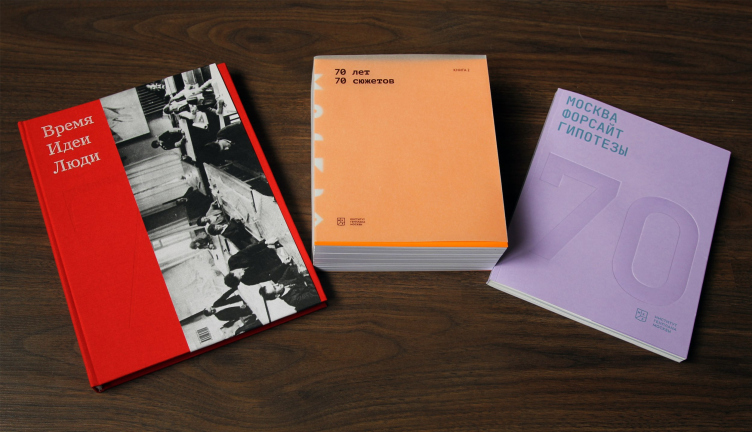

The project of the monorail of the Moscow Railway. Book #2. Pages 394-395. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

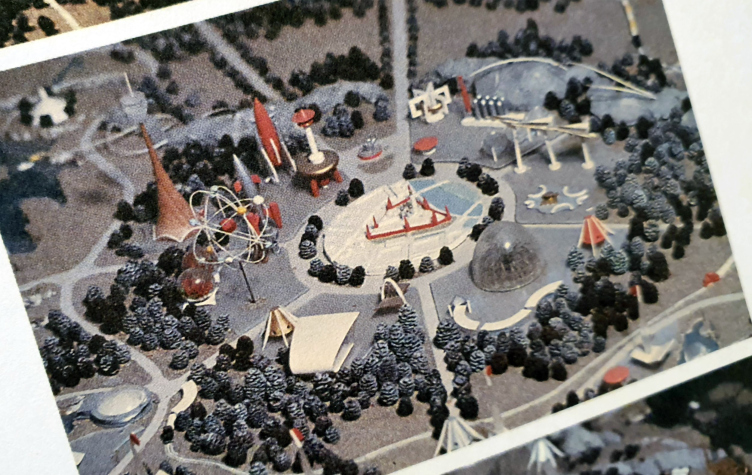

Still earlier, in the 1960’s, a children’s park called “Strana Chudes” (“Wonderland”) was designed at the other end of the city, composed of amusement rides superimposed on a relief map of the Soviet Union (Book #2, Page 604) . It was not implemented either.

The model of "Strana Chudes« (»Wonderland") children′s park in Mnevnikovskaya Poima. Book #2, Page 604. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Fragment. Photograph of the book page: Archi.ru

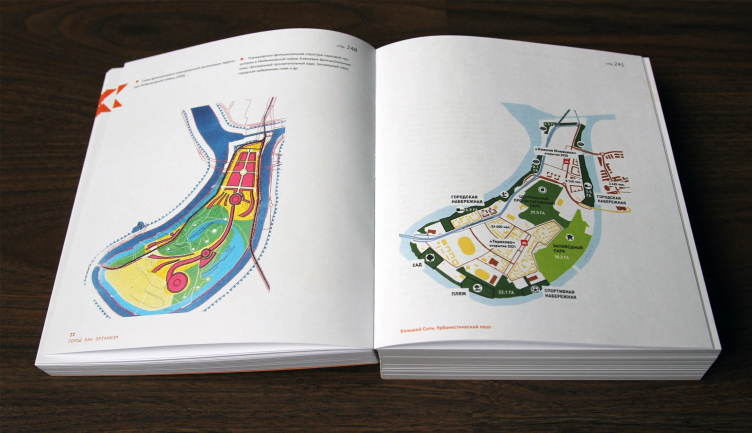

Later projects developed for Mnevnikovskaya Poima, 2000′s. Book #2. Pages 240-241. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

Examining the books, you can find a lot of such projects that are connected directly or indirectly to the existing reality. Things that look relevant are both recognizable and – by contrast – unimplemented, as an element of alternative history, which was lost before it ever began.

Let us start with the first book. It has the biggest format but it is not very thick – only 100 pages. In addition, it has virtually no project descriptions in it, just photos: the beautiful Margaret Thatcher and Nikita Khrushchev leaning over to examine architectural models, Alexander Kuzmin, and Yuri Luzhkov (let’s note parenthetically that Sergey Tkachenko praised him in his interview for adaptivity and excellent memory). The book also contains a lot of photographs of the employees of the Institute made at different times, so you can leaf through the book just scrutinizing the faces. Curiously, some of them are inscribed into the text in a traditional way, and some are added as stickers, as if somebody included into the book (or even bound into it) a set of postcards, which somehow brings up the memory of the seventies.

Book #1. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

At first annoyed at the fact that the stickers were not signed, I must do the editors justice and admit that all the photo captions are presented at the end of the book, along with the explanations of the acronyms that included both ones that were self-explanatory to me (such as CPSU, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), and quite unexpected ones, such as CHS (Central Heat Station), or LPZP (stands for Forestland Shelter Belt).

The mentions of the latter, it must be said, constitute a whole history of its planning and development, going from Moscow to Moscow area’s jurisdiction and back again, and finally, the destruction of some of the achievements by the 1980’s. According to Valentin Ivanov, at the Paris convention in 1984 the international experts admired the condition of Moscow’s forest belt: “this was an achievement of the Soviet town planning science, which they were able to implement and maintain until the 1990’s”. And here what it looks like today: “… I drive to my country residence past Skolkovo, and I am appalled at what they did to the forest belt <…> they did build houses there, just like in many other locations, but there is no longer the protection forest belt around the nation’s capital” – Ivanov laments. From the interview with the director of the Scientific Research and Design Institute of the “perestroika” days (1983-1988), we also learn that Valentin Ivanov (who is turning 90 this year) is working on his reminiscences, and in the five issues of “Architecture, Construction, and Design” magazine in 2000 he was able to cover – in a series of articles – “virtually the entire history of the Soviet landscape architecture”.

Incidentally, one of the key strong points of the first book is the bibliography. Despite the fact that, regretfully, there are no references in the historical essays, in the end of the book you may find a comparatively small but still representative list of publications that cover the work of the Institute – from this list, for example, you can learn that from 1970 to 1987 the Scientific Research and Design Institute published annotations of its projects and scientific papers. The article by Vladimir Yudintsev about the Master Plan of Moscow is available on the website of “Arkhitekturny Vestnik”.

Book #1. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

In a word, I would readily put my signature under the phrase that the Chief Engineer of Genplan Institute of Moscow, Mikhail Krestmein, put in the preface to Book #1: “Only very brave people could undertake the publication of this book”. And I would do that not just because “this is a great responsibility – interpreting historical processes and selecting historical personalities, about whom you want to tell the world”, but also because of the fact that the sheer volume of the material is enormous, and, due to its professional specifics, is difficult to perceive and present, even if we are speaking not about a casual reader but about an audience that is semi-professional, but not deeply submerged in the specifics of town planning.

An attempt to balance on the verge of a grand-scale publication and, let’s say “human-friendly” [the term is borrowed from web programming – editor’s note] essay is made in the second book, the largest of the three. The book has 798 pages in it (just two pages short of 800). It is beautifully bound and it is very comfortable to leaf through, even though the fashionable “bare” designer backbone is not devoid of some orphaned quality – probably, it is meant to stress that the publication has a “preliminary” character.

Book #2. Top view. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

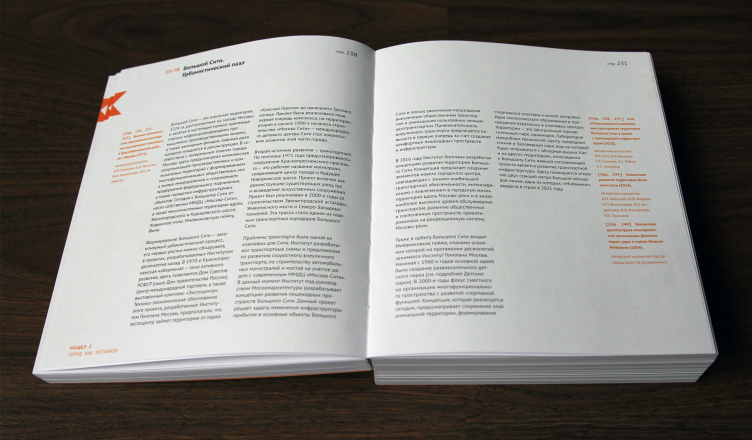

We will remind you at this point that in Book #2 the material is composed of 70 essays in accordance with the number of anniversary years; “70 years and 70 essays”. The essays, in turn, are grouped into 7 chapters – not in tens (as one might have feared) but thematically: from “spatial development” to “historical and cultural legacy” (how come it always ends up being the last to be dealt with?) The chapters are graphically marked on the book edge, but the first two are somehow combined into one; the sub-chapters are listed in the beginning of each chapter, even though I think they could be simply given in the contents. Curiously, the bibliography and the list of acronyms from Book #1 are duplicated here.

The backbone with chapter marks. Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

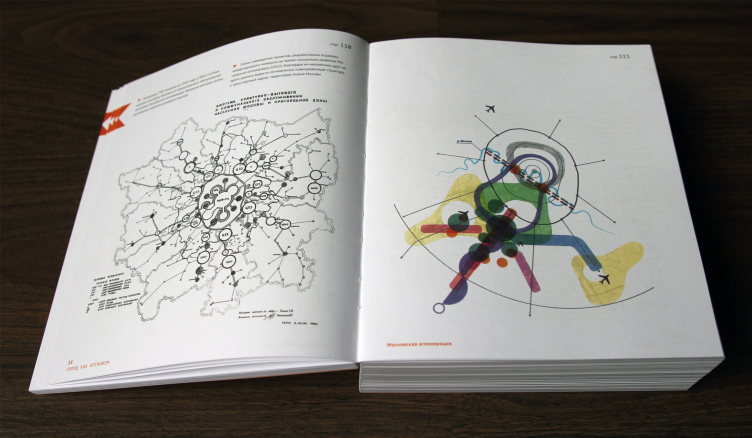

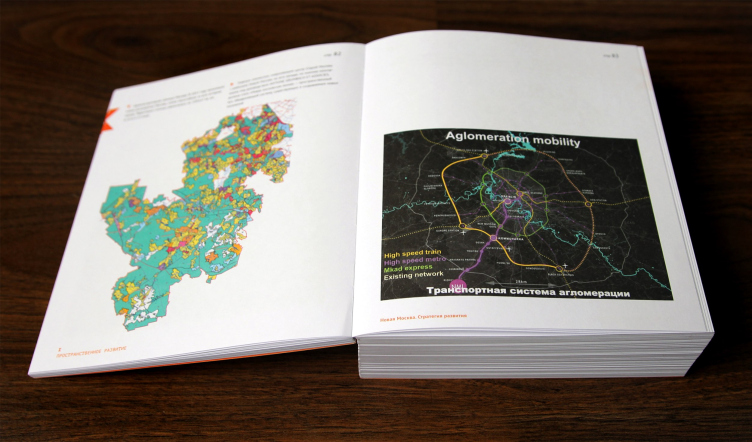

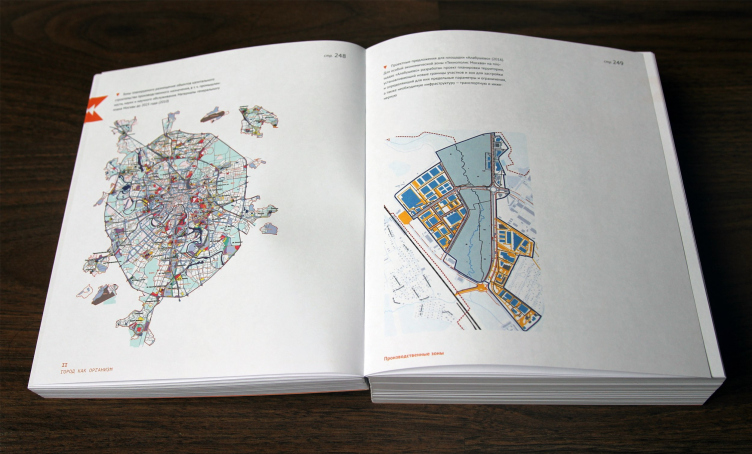

All these minor gripes in no way diminish the value of the publication. The essays are small, 1.5-2 pages long, but they have a more analytical character and make an easier reading than the ones in the first book because they briefly reveal the essence of each project, from the origins to the present. All of the projects are seemingly familiar, but every now and then you see them from an unexpected side. For example, the book includes an essay about the aforementioned forest belt, which in the early 1990’s “fell into disuse” as a notion; about the projects done by the Gutnov Group, whose sole implementation was the pedestrian Arbat Street, about the Moscow agglomeration, the appearance of which was considered by town planning experts before the very term ever appeared, i.e. starting from the 1932 contest for the master plan of the nation’s capital. Here we can also see the comprehensive scheme of the projects submitted for the “Big Moscow” competition, from which we can clearly read the direction of the southwest “protuberance”, which is quite a surprise considering the fact that in 2012 it seemed that most of the contestants voted for symmetric development of the agglomeration in all directions instead of just one.

Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

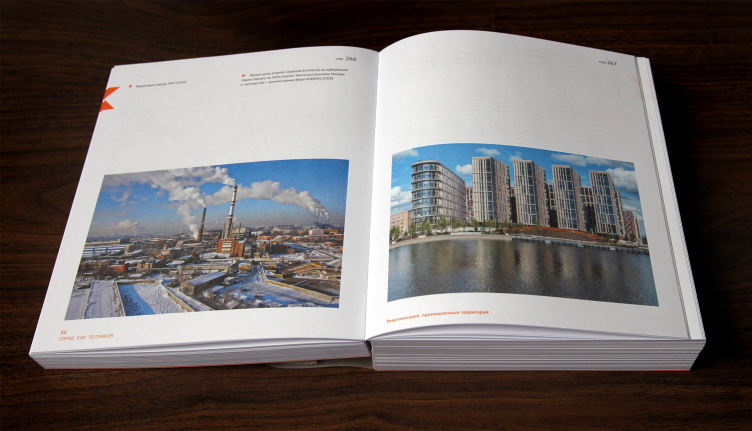

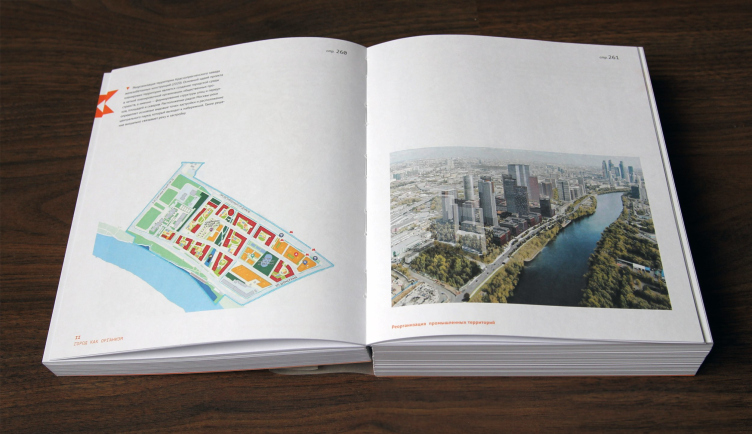

There is also an essay about New Moscow, and about the work that the Institute performed – periodically – for other cities in the Soviet times. About the industrial parks, about the Big City. About the water supply, heat, and electricity. About the public transportation: here we find out that in the place of today’s Moscow Central Circle, still in the sixties there were plans for building a monorail, and the Institute even in the 1990’s did not abandon hopes for building the Minor Ring of the Moscow Railway as part of the passenger transportation system.

My first impression was a mixed one – I could not make up my mind if it was all too much or too little. On the one hand, it may seem that you can write a whole book or even more about every facet of the art of town planning, and, on the other hand, there is too much of everything: too many themes, too many subjects, and too many projects, even considering the fact that in this case the number of essays fits the abstract figure of 70.

Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

Book #2. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

The short essays are complemented by commentaries to illustrations that constitute an additional part of the texts, because the illustrations occupy much more of the book than the text itself. Among them, there are lots of plans and layouts that I would be happy to see in a bigger format – so that I could read captions in the pictures. However, even in this state the information is abundant, and the book can quite be used as a textbook on Moscow’s town planning development. I had an urge to make this book a table one and peruse it on my own time. I think any architect – for the exception of those who know these projects by heard – should read Book #2 as a manual for mastering the subject.

Authors of Book #1:

Alexander Zmeul, Maria Troshina, Natalia Staroselskaya

Authors of Book #2:

Alexander Zmeul, Maria Troshina, Natalia Alekseeva, Alexander Molchanov, Nikita Suchkov, Olga Ivlieva

Both books have been compiled and edited by Alexander Zmeul.

Book #3. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

The third book, sporting a fashionable lilac cover, is devoted to the foresight for the next 30 years, i.e. to the future. Here again, if we are to look from the framework of the three-volume edition, changes are made not just to design, but to genre as well: the layouts, essays by analysts from different spheres, and quotes by architects, are interspersed by short stories of fiction. This, of course, is a deliberate move aimed at broadening the scope of statements: on the one hand, experts from different fields are involved in the process, just like they always were involved in conferences, not just town planners, but also economists, geographers, sociologists – and all of this resonated with the modern trends in town planning, which has long since stopped being an isolated science and is developing more and more in the direction of being a cross-platform discipline.

Book #3. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

On the other hand – authors and science fiction writers, where the term “science” can be interpreted very broadly.

The “literature” part, as it seems to me, serves to make the books less pompous, preventing the reader from taking at face value that what they are looking at are the real projects to be implemented in the future, and indicating that some of the ideas expressed at any foresight are based on analysis, but others can be pure fantasy.

On the other hand, it’s just fun to see how some of the writers indulge in retelling urbanist cliches, ecological dreams, and apocalyptic/digital apprehensions like the hackneyed one that we will have less face-to-face communication because of the spread of online technologies – but suddenly tear themselves away from all-too-predictable statements and make literature in the spirit of Bradbury’s Fahrenheit, or, if not Strugatsky brothers, then at least on the level of Lukyanenko.

I liked a story by Aleksey Evtushenko, in which a robot gets consciousness in the process of a quantum leap to Khabarovsk, and then a prodigy girl that he rescues sends him back to the rebel-held Khabarovsk again.

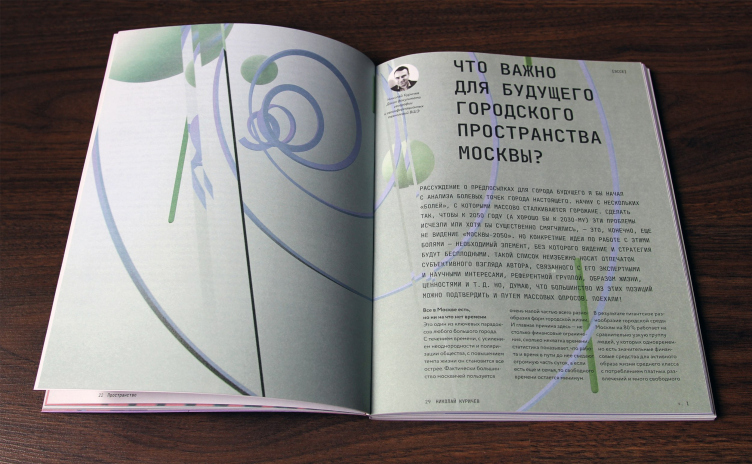

Just as interesting is the review by the head of the department of geography and geo-information technologies of the Higher School of Economics, Nikolai Kurichev, written in the genre of an analytical essay, which mentions the fact that the whole diversity of Moscow’s urban environment caters for people who have (1) spare time and (2) spare money on their hands – while others just struggle to make a living (and we are not speaking about migrant workers here), and are simply “not involved in the practices of consuming a fair share of the city space.”

Book #3. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

Another piece of interesting reading is a review by Ekaterina Shulman about the phenomenon of diversity as a social and cultural paradigm, in actuality devoted to the packing of cities and the reasons for migration.

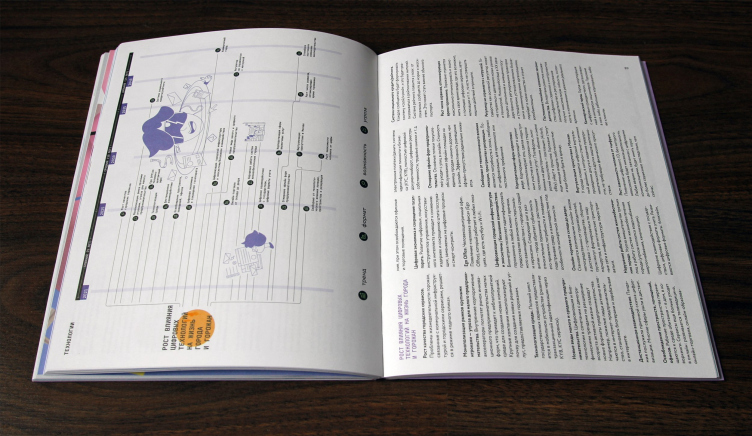

The statements are substantiated by diagrams that display the growth of creative economy, the number of muscovites that support “the new ethics”, subjectivity and mobility, or the growth of the social and spatial inequality and ghetto-ization; or the growth of the opportunities for cyber control. Various topics are covered. Meanwhile, “according to the members of the foresight, the main concept of the urban space of Moscow-2050 was that of a “service town” – says Elena Borisova in her essay, which comes first in the book.

At the same time, “what makes the “Moscow-2050” foresight special is the complexity of its topic consisting in the dynamics and alternative for developing a global city” – this is how the authors of the third book recap in the methodology of the foresight. Indeed, the very development of the megalopolis, which we don’t even know for sure is manageable at all, is a very complex task, and even more complex in the futuristic perspective. Because the future, as we know, is not written yet.

So, let’s be amazed at and happy with the bravery and professionalism of the authors of the three-volume edition, who ventured to make such an impressive string of anniversary events, from the exhibition in the Museum of Moscow to publishing this three-volume edition.

Book #3. 70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru

70-year anniversary of Genplan Institute of Moscow. The three-volume edition. Moscow, 2021

Copyright: Photograph: Archi.ru