The “Izvestia” city block next to the Pushkin Square is typically “Moscow”, even overly “Moscow”, in the sense that it represents all the main trends of the city’s architecture beginning from the mid-XIX century. This is a characteristic example of a melting pot of different styles and different epochs, but, luckily, this block nevertheless boasts architecture of decent quality, and there are no slums in it, either.

Aleksey Ginsburg has been working with this part of the city for about seven years already, trying to accurately restore all the architectural layers, and, wherever possible, resorting the historical justice – specifically, he uncovers and preserves the brickwork of the firewalls both for the tenement houses and for the “Izvestia” building, because these are historically correct. The result is colorful and fresh, very much “Moscow”, almost in the style of Lentulov: an exemplary restoration of a fragment of Moscow construction of days past; currently, four buildings of the first stage are complete. We already covered Bakhrin’s “Izvestia” building and Tyulyaeva’s tenement house. This article covers two other buildings: the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house, built back in the 1850’s, and the building of Ivan Sytin’s newspaper “Russkoe Slovo” (“Russian Word”) built by the architect Adolph Erichson in 1904. These two are situated at two opposite corners of the city block, eastern and western, one opening up the Malaya Dmitrovka Street, and the other gazing down the Tverskaya.

The Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh Estate

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Rediscovered in 2007 as a cultural heritage site, this place has lots of local lore connotations to it, including Pushkin’s visit to it in 1832 (more about it in the Arkhnadzor blog post of 2013); at that time, the work was only in the planning stage. It includes the walls of the manor houses of the late XVIII – early XIX centuries, which is generally characteristic of the houses of Moscow’s center; the neighboring Tyulyaeva’s house on the Dmitrovka Street also contains fragments of a manor estate. Meanwhile, the two-story house that we are seeing belongs chiefly to 1853–1856. This building has many more lore “bookmarks” – this was the place where the Moscow archeological society of Count Uvarov would have its meetings, and in 1947-1964, it hosted the editorial office of “Novy Mir” (“New World”) magazine headed first by Konstantin Simonov, then Alexander Tvardovsky. Then in the corner between the house and one of its wings a pub established itself, to be replaced by a casino in the 1990’s. At that time, the building was occupied by numerous tenants: offices, shops and nightclubs. But then again, after the restoration, most likely, the building will be rented out to offices again.

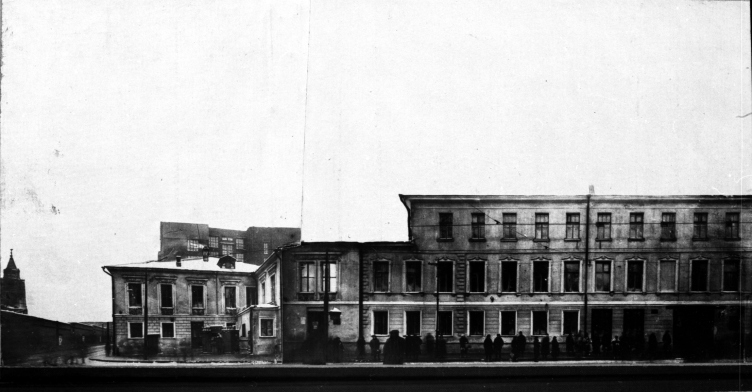

Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house. Archive materials / courtesy of Aleksey Ginsburg

The Pushkin Square. Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house. Archive materials / courtesy of Aleksey Ginsburg

The Pushkin Square. Archive materials / courtesy of Aleksey Ginsburg

Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house. Top view. Archive materials / courtesy of Aleksey Ginsburg

As for the pub and the casino, it was decided that these would not be restored; what did get restored was the little garden and the fence that existed here during the “Novy Mir” time. The architects also retrieved the lost cast iron balcony that was there in the square side. Also restored were the window frames: the outside “cold” window frame replicates the pattern of the historical windows known by photographs and surviving fragments, while the inside warm insulated glazing is virtually invisible from the outside. The meandering railing at the edges was replaced with a simple steel one.

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

In the 1930’s, the right-hand part of the house got a third-floor buildup; generally, the whole house consisting of a great number of layers is described by Aleksey Ginsburg as a “jigsaw puzzle”: it has really a lot of layers in it, no two rooms being exactly alike. “The walls kept “sprawling out”, and, generally, the house looked more like a location setting for the “Kin-Dza-Dza” movie (a cult Soviet sci-fi comedy – translator’s note) than something that belonged in the center of Moscow” – the architect shares; the wooden intermediate floors were deformed, and were plainly visible from outside. Later on they had to be replaced with reinforced concrete ones.

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

As far as the historical interiors are concerned, the architects only restored those that had the protected status: the main staircase and part of the second floor; stone stairs, stone inserts on the pilasters, and the plasterwork. It was impossible to keep the wooden roof above the staircase but it was replaced with a new one, wooden again.

One of the most serious problems was the salt which permeated the porous white-stone basement floor and the brickwork as well. It took a long time to clear all the walls from salt; this work continued well into the summer. After the procedure was completed the brick walls in the yard – as we remember, trying to be as historically accurate as possible, Aleksey Ginsburg leaves them made of brick – were treated with a water repellent.

After the restoration, the house was painted yellow instead of pink, probably because the style of its façades is sometimes defined as “late classicism”. It makes an excellent match to Tyulyaeva’s house on the Malaya Dmitrovka: yellow and salad green alternate with the bright terra cotta of the bricks. Yet another “neighbor” of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house is the Church of the Nativity on the opposite side of the street, one of the most ornate and famous churches of the XVII century. Although there is a 200 years’ difference between them, together they remind us of the low-rise Moscow, a city which after the construction boom of the late XIX – early XX century, and then the Stalin construction period, was changed almost beyond recognition.

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Ginsburg Architects. Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

From the opposite side, the manor house contrasts with the “Izvestia” building – just like old Moscow contrasts with new.

***

The building of the editorial office of “Russkoe Slovo” newspaper

Restoration of the Sytin house © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

While the manor house on the corner of the Malaya Dmitrovka street is a fine sample of the “old Moscow” part of this city block, low-rise, multilayered, yet cozy at the same time, the building of the editorial office, in which its founder Ivan Sytin lived and worked himself, quickly became the symbol of newness back in its days: from the sheer scale of the publishing business – by 1917, Sytin had bought out almost the entire city block, for the exception of Tyulyaeva’s house, shares Aleksey Ginsburg – to the Art Nouveau architecture with mascarons and a tile-decorated façade. The building started a new page of the history of Moscow, accounting for the “typographical” specialization of this part of the city. After the Great October Socialist Revolution, “Russkoe Slovo” was promptly shut down by the soviet power, even though it took the Bolsheviks a whole year to fully suppress it – until 1918 it kept fooling the Soviet authorities by being published under different names. Since 1921, the Sytin house hosted the “Trud” (“Labor”) newspaper.

In 1979 the Sytin house was relocated on 400 moving dollies, not for the purpose of widening the street but for increasing the area before the “Izvestia” building, built shortly before that time. Meaning – the building was moved not away from the Tverskaya Street and into the depth of the block but in the northwest direction: the two three-story tenements, between which in 1904 the editorial office of “Russkoe Slovo” was built, were already torn down by that time – in the 1960’s. The Sytin house was moved a whopping 33 meters over to the corner of the Nastasinsky Alley; in 1979 this procedure taking up not three months, as in the 1930’s, but mere three days and nights – hydraulic rams became much more powerful by then.

The relocation of the Sytin House, a photo from the "Tekhnika Molodezhi" magazin, №8, 1979, 4th cover (a painting by V.Ivanov)

There was also a huge monolith slab that was placed under the building – it was discovered in the course of work later on – the building also got extra reinforcements of steel beams, the entire first floor was encased in a metal bandage, and then the house got up and rolling on the 400 dollies. The rear wall of the building stayed where it was to be dismantled later on. Then the Sytin house did get restored, but, alas, in a cheap and somewhat sloppy manner: the historical woodwork of the window sashes was replaced with new ones that looked nothing like the historically correct version. “On the other hand, the protected status was bestowed on a room with Soviet-time walls and ceiling that was mistaken for the former Sytin’s study – Aleksey Ginsburg shares – it most likely dates back to the 1950’s and definitely cannot have any connection to Sytin whatsoever”. In the course of the 1980’s restoration, both of the building’s firewalls, hitherto totally neutral, got decorative arches with mascarons – probably, this happened between 1982 and 1985.

The Sytin house. Original condition. Archive materials / courtesy of Aleksey Ginsburg

The Sytin house in the 1930's. Archive materials / courtesy of Aleksey Ginsburg

The Sytin house after the relocation in the 1980's. The rockface pattern on the first-floor facades is clearly visible. Archive materials / courtesy of Aleksey Ginsburg

“It was interesting for us to restore things that were lost in the course of the relocation of the building and even before that time” – the architect continues. Among other things, the architects restored decorative walls with oval openings that masked the roof at the building’s side walls. They also restored the mosaic frieze with flowers on a golden background. Then they decorated the first floor with beige-colored tiles – it is hard to say when exactly this happened but by 1960 it was already replaced by rock-face stucco; washed clean the tiles of the upper floors, after which it turned out that during the soviet restoration it was mended with tiles of a different color – and the façade ended up being mottled; the later soviet additions were covered with varnish that ensured the unity of tone. All the old tiles got conserved. The window frames were made from scratch by old photographs. The windows of the first floor were diminished in size; Aleksey Ginsburg returned them the original contours with glass going all the way down to the pavement, this decision having been born not without difficulties: the approval board suspected that the architect was not so much restoring the historically accurate shop windows as putting in new ones of his own design. But it did work out in the long run.

The Sytin House restoration project

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Knyazev / Ginzburg Architects

The metallic framework of the cornice and balconies was rusted through but the architects opted out of recreating them altogether from scratch – instead, they reinforced them with “spike” anchors, fearing that in this day and age they would not be able to accurately reconstruct the Art Nouveau plastique, and thus the cornice and balcony remained the true historical originals. From the opposite side, the decorative arches of the early 1980’s on the firewalls were kept intact.

The original staircase of Sytin’s “Russkoe Slovo” also got dismantled in the 1980's, when they were building, from the side of the Nastasinsky Alley, right next to the replaced building, the “Izvestia” concert hall which was later turned into “Kodak Kinomir” movie theater (closed down in 2012). In the period of 1980’s – 2000’s, the function of the grand entrance to the Sytin House was performed by “Kinomir” staircase. Now Aleksey Ginsburg and his team of architects have built inside a new staircase and a new set of utility lines instead of the one lost in the 1980’s.

Restoration of the Sytin house © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Restoration of the Sytin house. Facade fragment © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Restoration of the Sytin house © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Restoration of the Sytin house © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

Restoration of the Sytin house © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

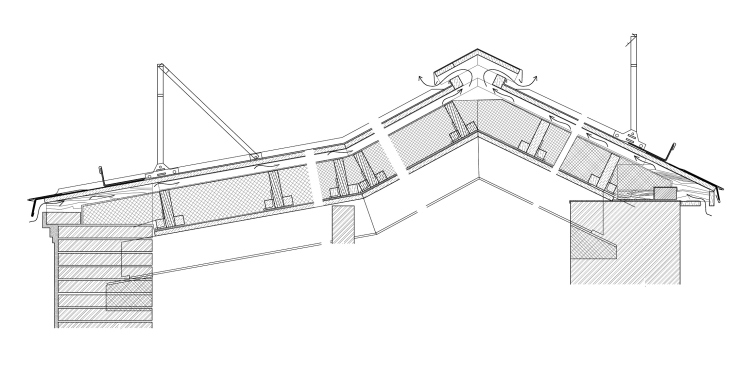

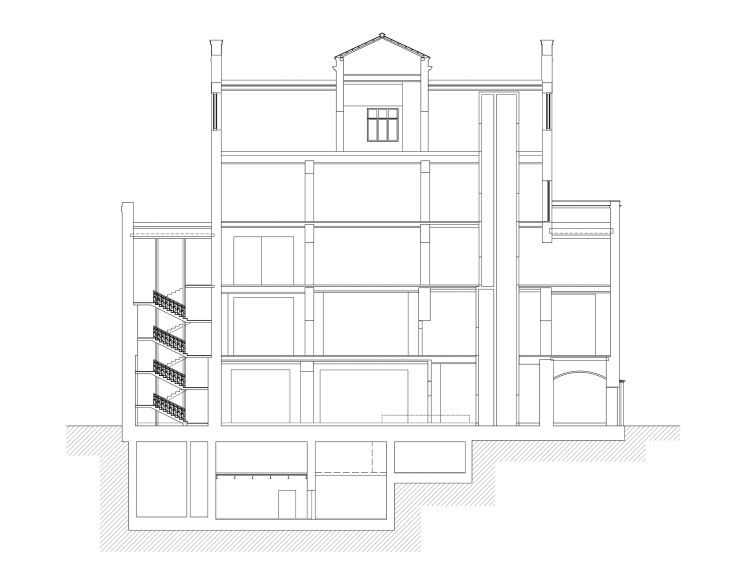

The maintenance floor is hidden in the cold attic under a hipped roof that has in it “gills” slits for airing the space, which helped to keep the traditional silhouette of the building without violating it with the popping up “mushrooms” of the ventilation shafts, – Aleksey Ginsburg proudly explains.

Restoration of the Sytin house © Ginsburg Architects, photograph by Aleksey Knyazev

The intermediate floors inside were designed by Vladimir Shukhov – the architect shares – and consisted of double-L beams with an increment of 1.2 meters and metallic membrane about 10 cm thick, covered by crushed brick. Seeking to avoid overloading the steel beams and thus putting them to a strength test, the architects introduced new monolith slabs that are situated slightly higher up, at the same time preserving the Shukhov structures and the surviving plasterwork in them. As for the plasterwork, the architects opted out of decomposing it – due to the fact that the owners are planning to rent out the premises without remodeling, the condition of the plasterwork remains on the tenants’ conscience. The two lower floors of the house are expected to be occupied by shops, the two upper ones – by restaurants.

***

I think that this story shows rather clearly how much Aleksey Ginsburg is into the idea of restoring old buildings and preserving both their historically accurate image and original elements. This recreation is, on the one hand, meticulous and painstaking, but, on the other hand, it is meant for life – these buildings will not be turned into museums; they will function and continue to serve people. This, however, entails a number of compromises: the architecture purists would probably suggest that the architects restore the publishing function of the Sytin house and completely recreate everything that was inside... As a matter of fact, one of the problems of our time is the struggle between perfectionism and pragmatism, and their inability to come to terms with each other. However – let’s use this term – “old Muscovites” ask too much, and the others, based on these grounds, studiously ignore their demands, doing just what they think to be the right thing. The hard work of Aleksey Ginsburg is the reverse example, a case of reasonable compromise, which I think, will do this city a lot of good.

Restoration of the Sytin house. Roof cross-section © Ginsburg Architects

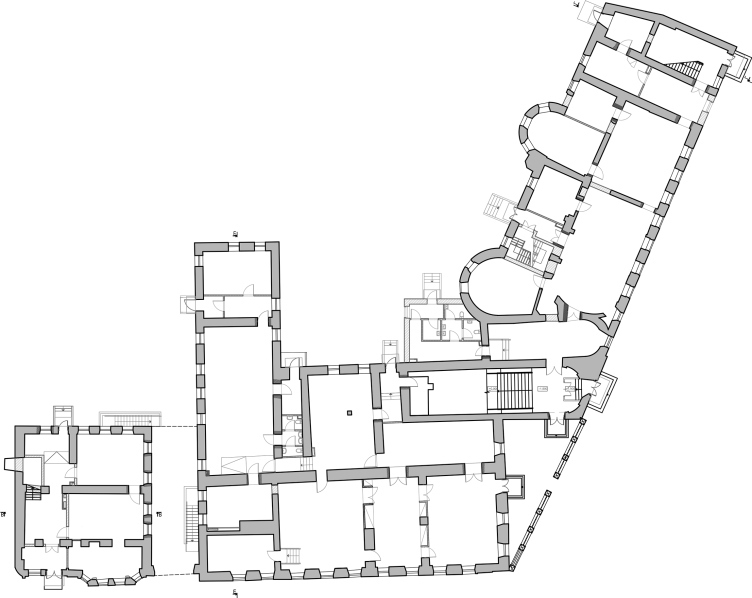

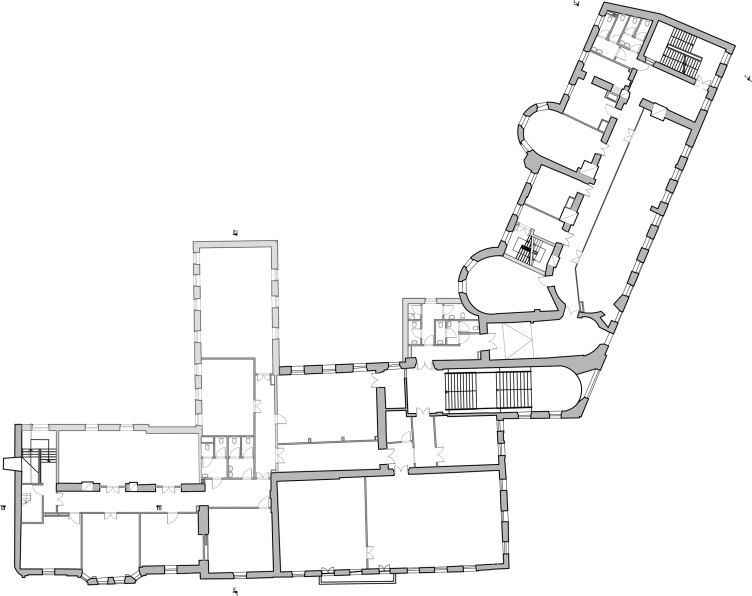

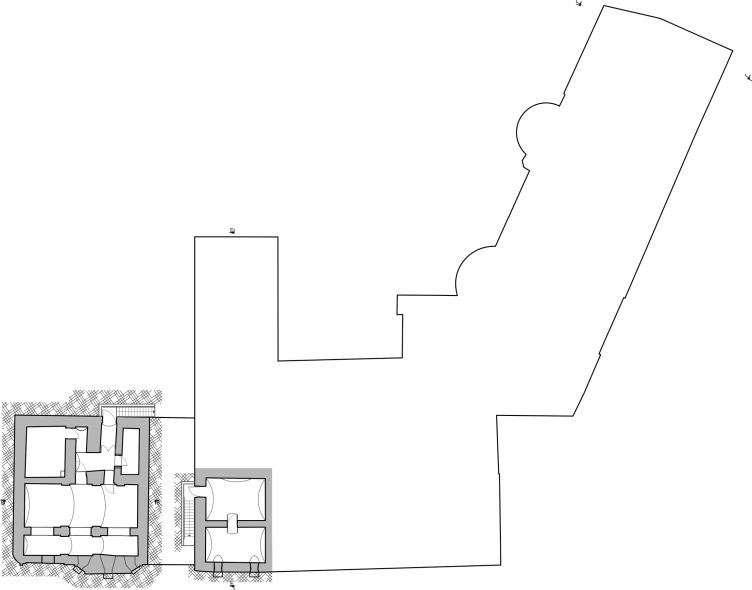

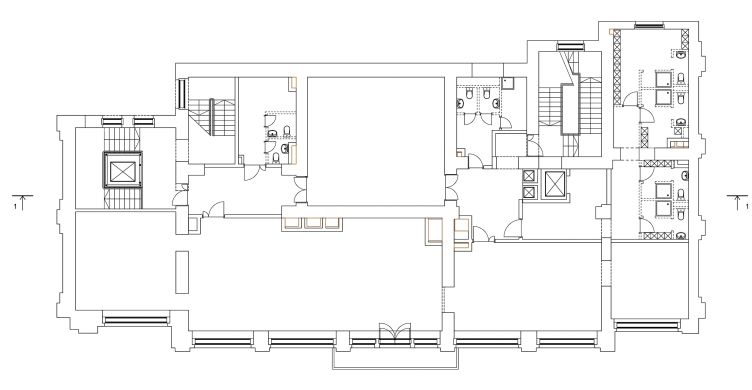

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Plan of the 1st floor © Ginsburg Architects

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Plan of the 2nd floor © Ginsburg Architects

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Plan of the basement © Ginsburg Architects

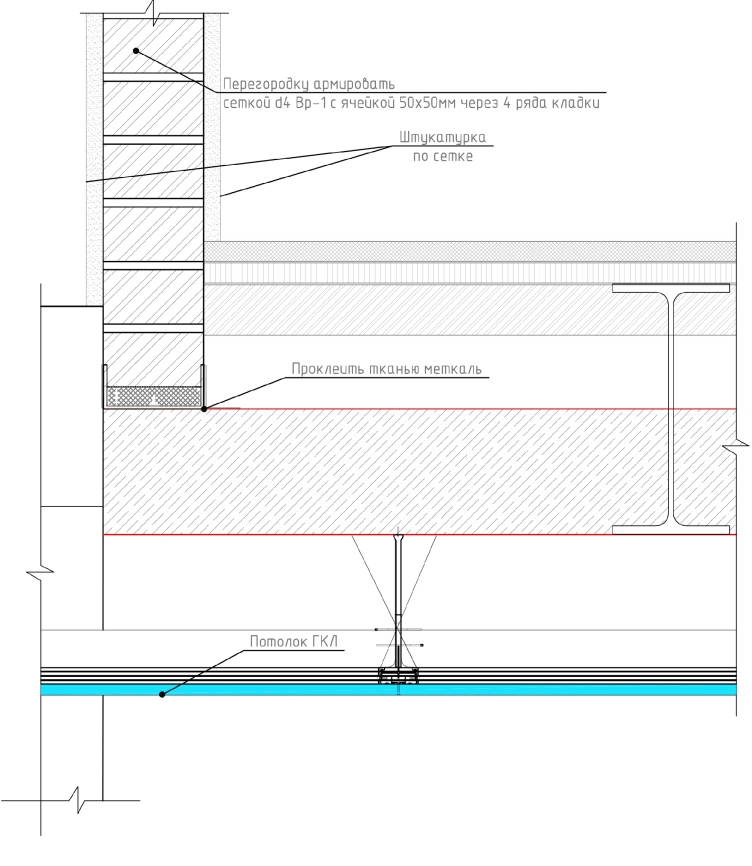

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. Section E-E © Ginsburg Architects

Restoration of the Dolgorukovykh-Bobrinskikh manor house on the Malaya Dmitrovka Street. The point where the intermediate floor joins the staircase © Ginsburg Architects

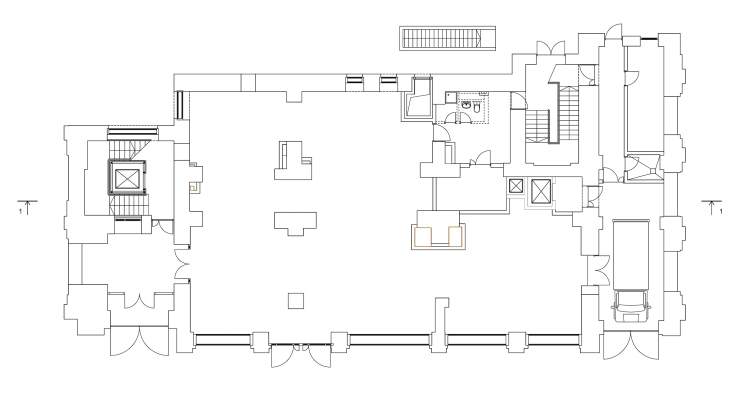

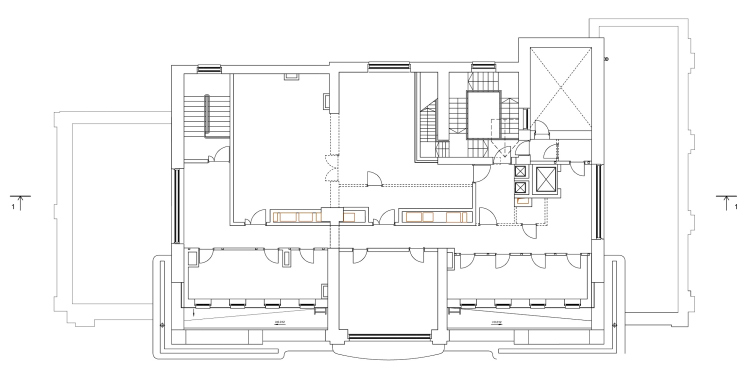

Restoration of the Sytin house. Plan of the 1st floor at mark 0.000 © Ginsburg Architects

Restoration of the Sytin house. Plan of the 2nd floor at mark +5.107 © Ginsburg Architects

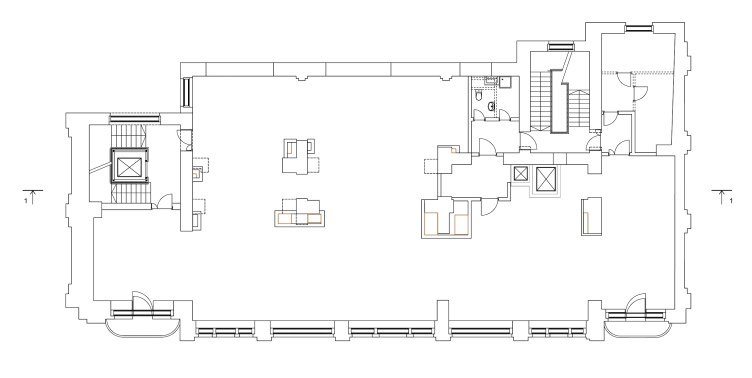

Restoration of the Sytin house. Plan of the 3rd floor at mark +10.433 © Ginsburg Architects

Restoration of the Sytin house. Plan of the 5th floor at mark +20.542 © Ginsburg Architects

Restoration of the Sytin house. Section 1-1 © Ginsburg Architects