From inside the profession that’s not the way it looks. Architecture is a fascinating process. A project is born and grows, and you help it grow. Your office is your team. Every team has a captain, and then there are all the other team members, and the captain cannot manage without them or they without him. For someone in this team three qualities are important: love for his profession, ability, and ambition. What can be better than to play in the same team as people who are capable, ambitious, and love what they do? As for builders and civil servants, they are a circumstance which has to be taken into account, calculated, and bypassed. With clients, it’s important to have a clear understanding of the situation. I always tell my staff that clients are not our partners. They are an element of nature. And like any element – wind, water, or earthquake – they possess energy, and this energy is something we need to be able to exploit. You can resist it, as a dam does, and it will press against you. Or you can set a sail against it and sail away – close to the wind maybe, but at least you’ll be sailing. Otherwise, you’ll be crushed, or you’ll crush your client, but either way nothing good in terms of architecture will come of it.

But what’s the point of this endless tacking to and fro? What’s so good about it?

As human beings we need to create – to make things which did not exist before us. Architecture is the best way to achieve this. It’s a lifestyle, a hobby, a sport.

But if it’s a sport, who are you competing against? Your colleagues? Space?

No, it’s not the kind of sport where you beat someone. It’s not a game, but sport in the sense of process – when you’re constantly taking decisions, fighting against yourself, against circumstances. It involves strategy and tactics. Like, for instance, sailing. And there’s no need to beat anything or anyone. It’s more like the work that the gardener does. Something grows according to its own laws, and you help it grow.

The project grows of its own accord, rather than out of you? Out of what, then?

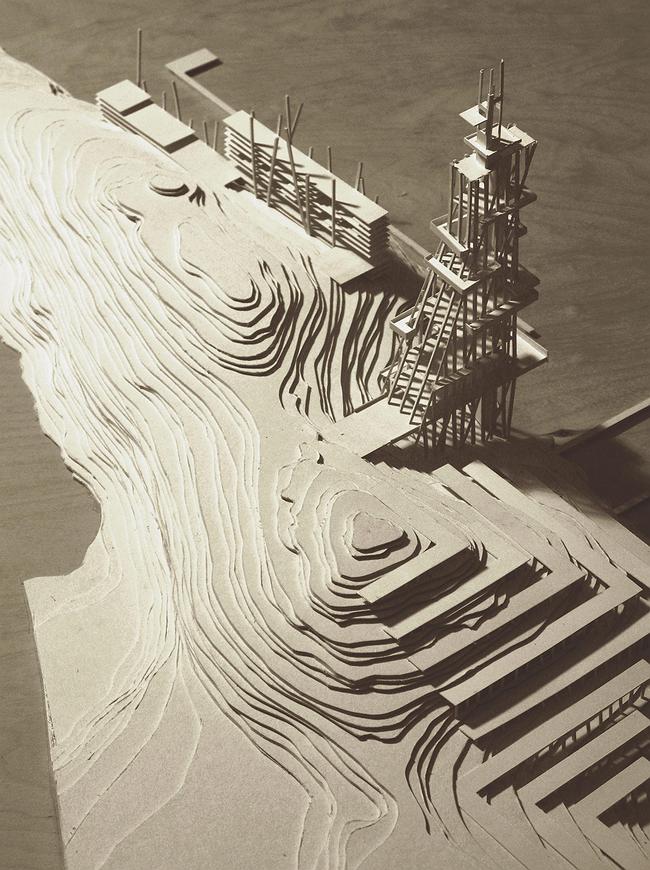

There is a set of circumstances – spatial, economic, functional – that give rise to a certain chromosome – a seed, a model of the future. Or to be more precise: these are circumstances in which a particular chromosome can survive. It subsequently grows to become an organism. And your task is to ensure that this organism grows normally.

But how do you know which chromosome is the right one?

Unfortunately, only by natural selection. To begin with, you draw lots of hieroglyphic signs, each of which contains a spatial model – and they die out. And the one that does not die is the normal one. You kind of test their viability.

So it never happens that you arrive at a site, look at it, and a solution occurs to you.

No, that never happens. To begin with, when you see the site, your first feeling is perplexity. Here your only salvation is experience – the knowledge that on any site it’s always possible to build something. This is calming. But you never have the feeling that you must do something a particular way. In general, this first moment, when you have to create a multitude of non-viable chromosomes, is the most difficult.

And how long does it last? Do they take a long time to die?

It’s usually quite quick. Like with a dandelion: there are a huge number of seeds, but then they quickly scatter. The more experience you have, the quicker you learn to distinguish solutions that are non-viable. However, it sometimes happens that you think you’ve found it – the simplest and most effective solution, – but then, when you embark on the next stage, you run into some irresolvable contradiction. You realize that you’re working violence on life and nothing good will emerge. Then you go back and have a look at how the other embryos are getting on. The end result should be a system which satisfies the entire set of circumstances and translates these circumstances into a spatial organism. In architecture I sense a sort of agricultural cycle. First you plough, then you sow, and then the crop begins to grow. At a certain moment you have to let a project go and feel that it is already ripening by itself. And then you harvest. And it’s the same with every project. And that’s what I like most of all.

If a project is a chromosome that grows by itself, then how do you know what shape it should take in the end?

There’s no way of knowing. It must grow by itself; all I can do is protect it. There’s a very strong resemblance with a plant. A tree has a morphology. It must have roots, a trunk, branches, leaves; but it lacks a finite external form. It has grown the way it is, and that’s its form. I think that looking for an external form is a kind of violence; form should occur by itself.

So there’s no point, I take it, in asking what form is beautiful.

‘Beauty’ is a category that’s badly lacking in clarity. If someone says he’s seen a beautiful house, that doesn’t mean anything to me; I am unable to picture this building.

But there are certain, say, ideas concerning the perfect architectural form. Proportions, textures, composition, mass. Styles.

Proportions and textures are something that all living organisms have. Trees, cats, elephants. This is important for my understanding of architecture too. But I think you could say that a tree has no composition and its distribution of masses is variable. And this, I think, is the wrong direction in which to look. I don’t like architecture that is dressed in something else. Niemeyer is right to say that a building should be visible in its entirety in concrete. It’s the same as with paintings or graphic art: I prefer minimalist graphic art in which a single line says it all. Like the works of Picasso or Serov. A line should not become overgrown with hatching. A building should not become overgrown with wool. Styles are either for the critics or for epigones. They are a means of classification rather than of art. A hare does not know that it is a hare; it simply is. Buildings should come into existence in the same way. An architect who tries to design a Constructivist building today is just as much a stylist as someone who designs architecture in the Classical style. Initial, a priori forms can be only very general and primitive – you might say, for example, that here, on this spot, there might be something big or long or red. But to say that here there should be a particular style is violence. It’s wrong even to think that way.

Because there’s no way to attain this style?

Because there’s no way of protecting it. It won’t survive.

Protect it from whom?

From the whole set of circumstances. It’s a non-viable embryo.

So a building can grow only from its site and function. And never from the history of art, tradition, from an abstract sense of beauty?

That’s right. And there’s also a criterion of organic architecture. If architecture is organic, then it is beautiful.

But historically architecture was born from an a priori method.

For example?

Well, for example, Le Corbusier. Architecture that is created for any site. For Berlin, Marseilles, India. You have a modulor, a clearing and that’s all you need.

It’s a miracle. This architecture is ideally suited to its location; it creates a point of emphasis for the entire space around it. But even this is not the point. There you have a higher form of organicity; Le Corbusier created a perfect organism. Like, for instance, an elephant or a cat. If a cat moves from place to another, you can’t say it has lost its organic quality? It’s the same with Corbusier’s house.

You aspire to miracles?

Of course.

a part of the facade