“Conservation was invented at the same time with modernism”

Rem Koolhaas

Rem Koolhaas

On Wednesday, June 10, there was held the presentation of the new building of the museum of contemporary art "Garage" that is now open to visitors.

On the outside, the building indeed looks absolutely new - this is an ascetic parallelepiped clad into panels of cellular polycarbonate with an only "slit" window that actually stretches from the long side of the facade onto the short one. The semitransparent material delicately reflects the sky and the surrounding park, at the same time, without making any attempts at mimicry. This is something like the box of the Little Prince from the book by Saint-Exupéry that allows for placing any kind of exposition inside - and what solution can fit the needs of a museum of contemporary art better? The polycarbonate panel elevated over the main entrance gives the building's silhouette a little more variety, and enhances the image of the technological shell that provides for the inside microclimate perfect in every respect.

From under the panel, there shows up a huge, more than nine-meter tall, picture by Eric Bulatov named "Everybody Welcome to Our Garage!" (according to Snezhana Krsteva, the exhibition curator, this is the largest canvas ever painted in Russia since "The Appearance of the Messiah to the People" by A.Ivanov), a cheerful-looking and life-affirming billboard in the spirit of the twenties "Growth Windows" that lifts before the side observer the veil over the contents of the mystery box. Probably, this is the impression that "Garage" is meant to produce on the visitor unfamiliar with the history of this project.

Facade of the museum. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The canvas by Eric Bulatov meets the visitors at the entrance. In actuality, these are two canvases. One is turned outside, and the other - inside, into the foyer. The artist painted this works specifically for "Garage".

The main entrance of the museum. The elevated panel over the main entrance provides the view of the foyer and the work by Eric Bulatov.

There is no fooling us, though. We, of course, know that the center of the contemporary culture "Garage" that started its way seven years ago under the roof of the monument of architecture - the Bakhmetyevsky Garage designed by Konstantin Melnikov - now conceals inside of it the fine specimen of soviet modernism architecture adjusted to fit the needs of today.

On the 1st of May of this year, the center of modern culture was transformed into the museum of contemporary art, and the framework of the cafe "Seasons of the Year", now carefully restored, will no doubt become one of the most important exhibits of the new museum. Of course, the old walls, the mosaic "Autumn", and the prefabricated concrete are all valuable not only as such but also as parts of the dialogue with the new shell and the functional interventions that the designers made into the existing structure of the building.

Adjusting the space of the soviet cafeteria to become a museum of contemporary art was, according to Koolhaas, not that difficult, after all. "The building initially included various spaces that we were able to adjust to be fit to exhibit the specimens of contemporary art without making any radical changes to them" - he shares. Indeed, all the existing walls, floors, and columns, and almost all the staircases were kept intact. Generally, one can say that the result is surprisingly little different from the project that was presented to public three years ago (at Archi.ru, this presentation was covered by Alexandra Gordeeva in the article "Reconstruction by Koolhaas"). If we are to speak of the critical project solutions, only the movable mezzanine balcony in the central foyer had to go. But then again, this was done not because of financial constraints but because the functional contents of "Garage" was slightly reconsidered after the new curator, Kate Fowle, was appointed a little over a year ago.

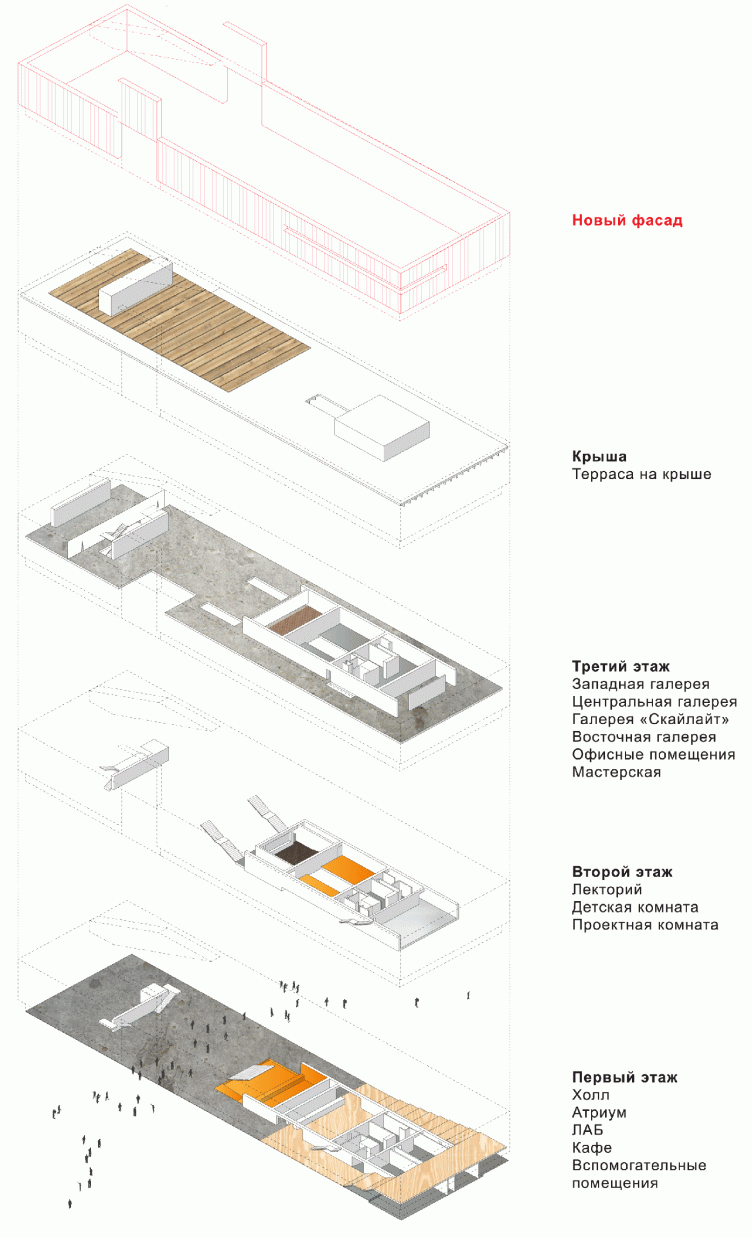

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. The transformation strategy © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

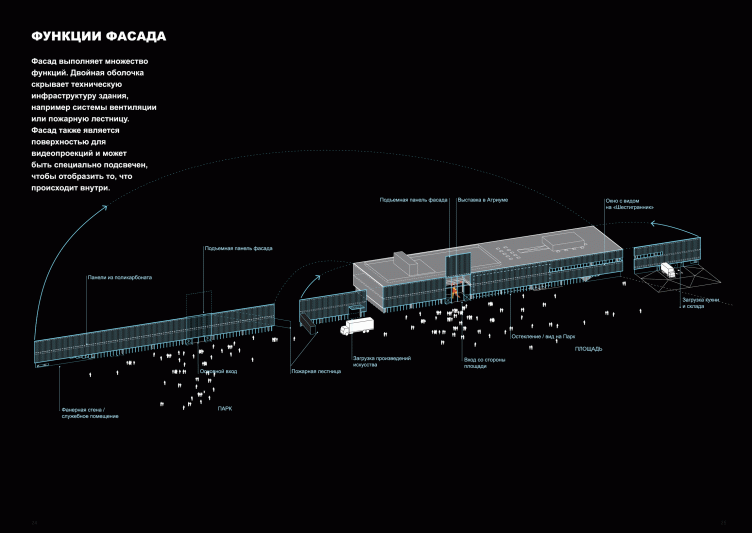

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Functions of the facade: the double casing conceals the structure of the building © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

It was also right about that time that the construction started. Koolhaas did not make any secret of the fact that "the main problem of the project was registering our ownership so that we could get started". So, turning the modernist ruins into a contemporary building took less than a year and a half. Such a speedy pace of construction is truly amazing, particularly considering how many new techniques and technical novelties were implemented. The leader of BUROMOSCOW Olga Aleksakova who took part in developing the working documents and in the author supervision, shared that the decayed floor slab panels had to be reinforced with prefabricated reinforced concrete. The floor slabs also conceal the climatic system - the water pipes that must hear the building in winter and cool it in summer. At the same time, the entire MEP layout, just as was promised, is hidden between the two layers of polycarbonate casing of the building. The facade of flammable polycarbonate became a problem in itself - the architects had to obtain special technical specifications and conditions. "This building is a precedent" - Olga stresses. Even the plywood floors of the cafe and in the new mezzanine seemed inadmissible to a lot of people. The plywood and the concrete floors, the polycarbonate, the steel grille used for flooring - this is a short list of the materials used in "Garage", the materials that are traditionally considered to be only fit for technical and makeshift structures, and definitely out of place in such a high-profile building as a museum. For OMA, however (just as for the Dutch architecture in general) using the cheap materials for decoration is one of its trademark techniques.

Facade of the museum. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

"Garage" viewed from Gorky Park. When the landscaping work is over, the fence will be removed. It is already seen that there will be little difference between the museum and the surroundings.

The polycarbonate facade starts two meters up from the ground. The concrete floor of the foyer is the same level with the outside ground. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The only window is situated on the third floor. At this place, the outside layer of polycarbonate gives way to glass.Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

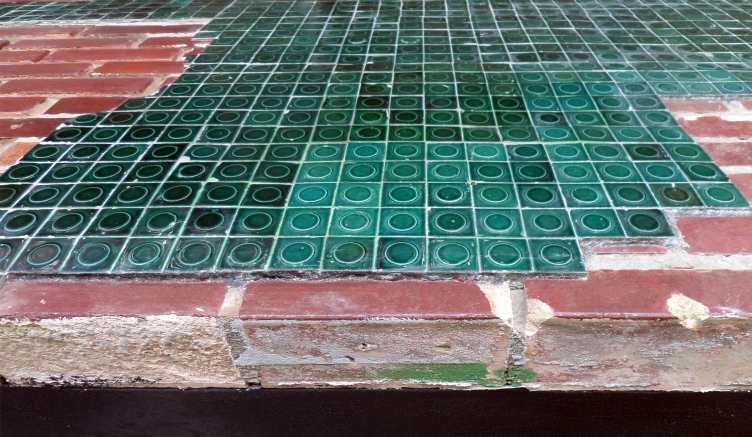

The most expensive decoration materials in this interior are, by far, the surviving glass tiles and the glazed bricks of the soviet cafe. They were partially taken off the walls, sent for the restoration in Italy, and then carefully put back in place. But then again, Koolhaas was not after restoring the original look of the building, and the "ruin" image was left almost intact. From the jagged edges of "Autumn" mosaic, the glazed bricks show coming from a different time layer, and, higher up, left completely to be plainly seen, there is uneven brickwork of regular bricks, earlier concealed by the hanging ceiling. In conjunction with the modern industrial materials, in some parts of the building, all this creates a completely "backstage" garage atmosphere.

The mosaic "Autumn" has survived into the present since the soviet days. Where the mosaic is broken, the resored glazed bricks are seen. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The surfaces decorated by the glazed bricks only look unkempt from a distance. This "negligence" is in fact well thought-out Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The overview from the grand entrance. This is the space of the maximum height, from the first floor to the roof. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The zone around the open staircase leading onto the roof - one of the most "garage" places of "Garage". Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The bright orange cloakroom is one of the few interventions of today's architects into the modernist interior. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The main facade of the museum. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

One can still hardly refrain from comparing the new "Garage" with a brand-new garage of profiled sheeting into which a sentimental car owner dragged what was left of his first car and put its skeleton on four brick stacks instead of the long-gone wheels. Then this car enthusiast dusted his car seats, polished the cracked windows and wiped his tear of tenderness. "Why keep this old miserable wreck?" - many people wonder. One commentator on Facebook went as far as to suppose that this western "satiation evokes the appetite for the incomplete, imperfect, and tragic".

This is not what it is all about, however. Koolhaas many times complained that "the more monotonous and faceless architecture that appeared after World War II, has few admirers and still fewer defenders". Sharing about the project of "Garage", he developed this idea: "The movement for saving the historical legacy was always aimed at saving what is old, valuable, and beautiful. We have always insisted that the usual common things are also worth saving - so as to be able to explain later on to our kids how people lived in the past".

So, for Koolhaas, this building is not just another project - it's a manifesto. With it, he not only conserves a fragment of the typical soviet life but also voices his disagreement with the commonly accepted concept of preserving the antiquities.

One could arguably say that the mistake that the architect is pointing to can be actually traced back to the very origin of this concept. The movement for preserving the historical monuments and the modernism that appeared at about the same time, were initially sworn enemies and remained them for a whole century. This fight went on with varying success, and not in the Soviet Union alone. For example, back in the seventies, in West Berlin, they massively "simplified" the facades of the buildings of the epoch of eclecticism. Now the modernism of the XX Century has dilapidated itself and became a historical style itself - meaning, lost the war - possibly, it is time to reconsider the conservation before the architectural routine of but half a century ago turned into a fleeting memory.

Not everyone agrees that such manifesto is compatible with a fully-fledged museum of contemporary art. Valentin Dyakonov from "Kommersant" thinks that the new "Garage" cannot be considered to be a "contemporary exhibition venue convenient for exhibiting works of art of various meaning and magnitude". "Koolhaas - the critic continues - himself wrote the concept of the future development of "Garage": the former restaurant where our fathers and grandfathers would sit down with a mug of beer, can only serve as a museum of our inglorious soviet past".

At first sight, this standpoint makes a lot of sense. Is it by chance that most of the expositions that the new museum showcases, can be traced back to that particular period of time: they show the history of the soviet art, about the American exhibition of 1959 in Sokolniki Park, about the Russian cosmism, and so on. Even the forty-six-year-old Rikrit Tarivania in his brand-new project "Tomorrow is the Question?" tries to make a connection with the past, turning to the creative work of Czech artist Julius Koller and treating the visitors to the nostalgic pelmeni.

Fragment of the installation by Rikrit Tiravania "Tomorrow is the Question?" Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

But today and yesterday are also the question! Building, by coincidence or by design (and I still regret not having asked which) the new casing around the old modernist building, Koolhaas stressed the inner conflict and the controversy of the very term of "museum of contemporary art". A museum is by definition an institution that collects, studies, keeps, and exhibits the objects of culture - meaning, something that already WAS there, something that belongs to the past. The present is by definition made of the events that are taking place now, at this very moment. All around the world, the museums of contemporary art exhibit the works of the artists long gone that are by inertia considered "contemporary". True, now and then a really contemporary work comes up but these works are kept in the museum's vaults and also become part of the "history of arts". "Garage" in this sense is no exception. Hitherto, as a center of contemporary culture, it exhibited the works from the other people's collections, thus participating in today's cultural life. This year, becoming a museum and planning to gather a collection of works of modern art of its own, it has embarked on this controversial journey.

With the spreading of museums of contemporary art as an independent cultural institution, the designers more and more - again, by coincidence or by design - tried to react in different ways to this controversy. The hysteria of the museum buildings of unusual shapes with, of course, Bilbao Guggenheim museum at its peak, has gradually abated giving way to the neutral "washing their hands" semitransparent boxes where you can exhibit whatever you want. Koolhaas, on the other hand, the way I see it, made a new step on this journey, sharpening the question yet again. The ruins of a modernist (meaning - "contemporary") building are not enough to be a museum exhibit as such. The museum in its entirety, i.e. the casing and the ruins inside of it, however, do have the right to claim the exhibit status. This object is a manifesto - both for architecture and especially for the modern culture; its power of statement can probably only be paralleled by the "Fountain" (a porcelain urinal, not to mince words) by Marcel Duchamp. Such a double-meaning comparison we got here but it's better than nothing. Because the main task of the modern art is to provoke, to explore, to discover, and, most importantly, to pose questions rather than answering them, is it not?

Valentin Dyakonov is sure right claiming that the curators will have a hard time exhibiting in this museum works of art that are not connected with the soviet cultural context. But, then again, no one said that this would be a walkover either.

At the end of the day, it is amazing that only one critic gave a negative response. Duchamp's ready-made caused a lot more vocal criticism back in 1917.

Oh, by the way, the toilets and the urinals are great in this museum, too.

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Model. © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Model. © OMA

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Model. © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Model. © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

Museum facade. Reflection of the sky Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The elevated platform of the main facade from the inside, from the terrace on the roof. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

Behind the polycarbonate wall. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

Behind the polycarbonate wall. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

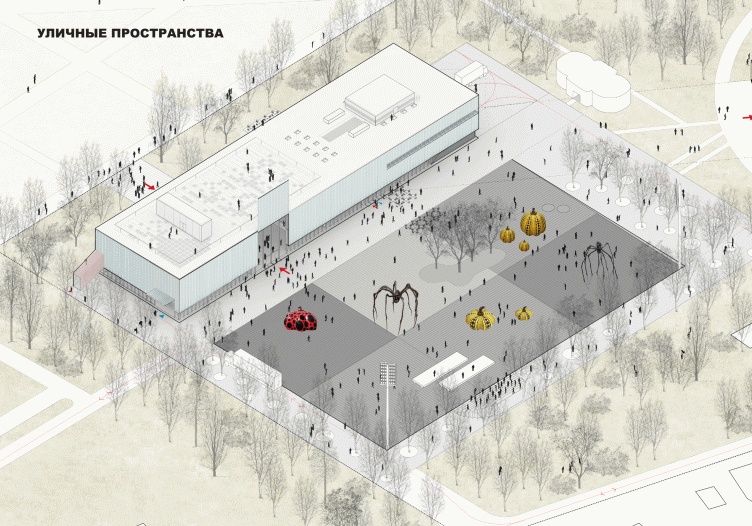

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Territory. Plan © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

The landscaping part was done by Anna Andreeva's "Alphabet City" bureau. As she shares, the task was to create a "forest" in which the pavilion would "dissolve". Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

The organizing of the territory around the museum was done by "Project Meganom" The work is not yey completed but observingt the working process was interesting. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

On the left: flooring of wooden cubes. On the right: stone pavement. Photograph © Ilia Mukosey

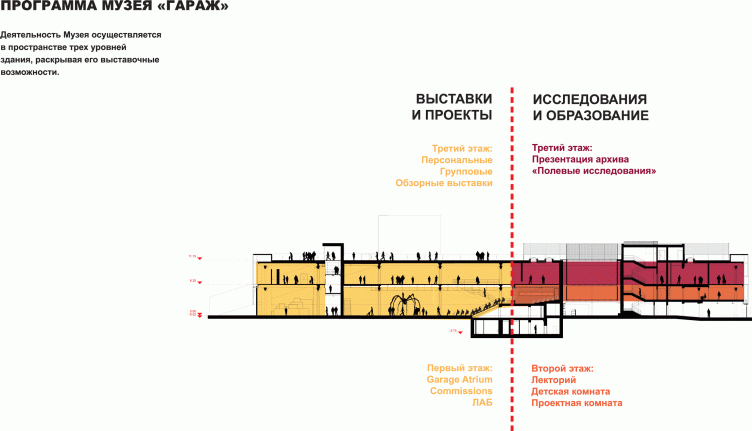

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Section view of the building and the functional program © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

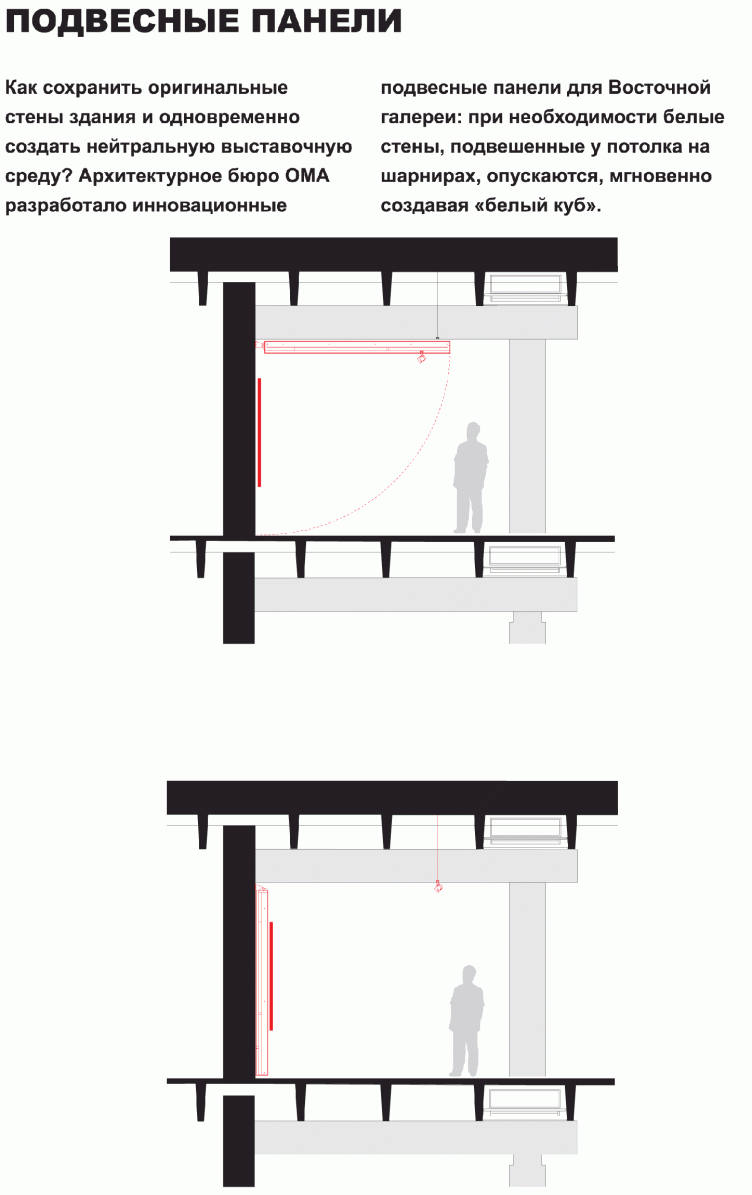

"Garage" Museum in Gorky Park. Suspension panels. OMA developed innovative panels specially for the Eastern gallery. Section view © OMA, FORM Bureau, Buromoscow, Werner Sobek

Rem Koolhaas (behind the glass) gives an interview on the day of the inauguration of the new building of the "Garage". Photograph © Ilia Mukosey