The land site upon

which this house will be built is rather large but is burdened with a whole

bunch of encumbrances, so, when getting down to working on this project, the

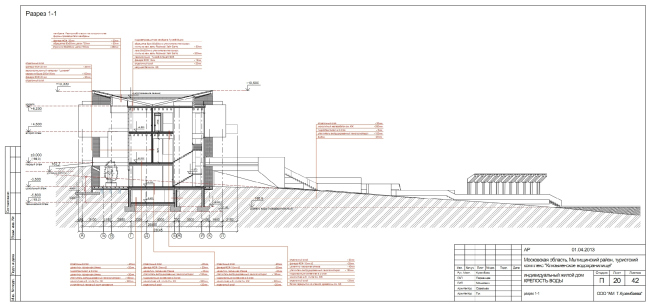

architects from the very start had their hands tied. For one, the construction

blueprint, seemingly vast, was in fact less than moderate: the water protection

zone and the communications running through the site rendered the house

construction possible only on a small rectangle of land. And, due to the fact

that the customer asked to build for him a house of more than

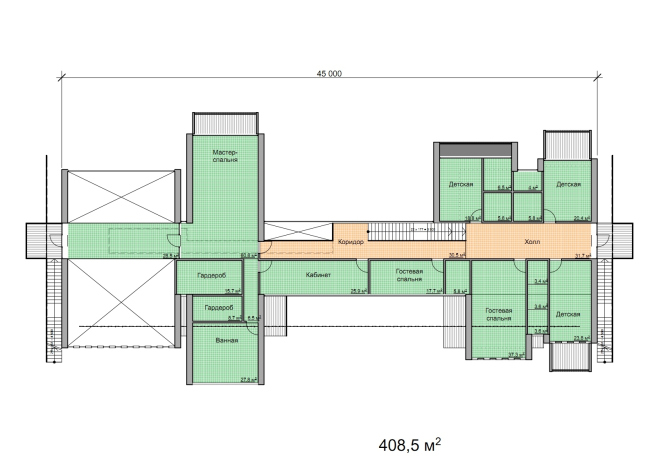

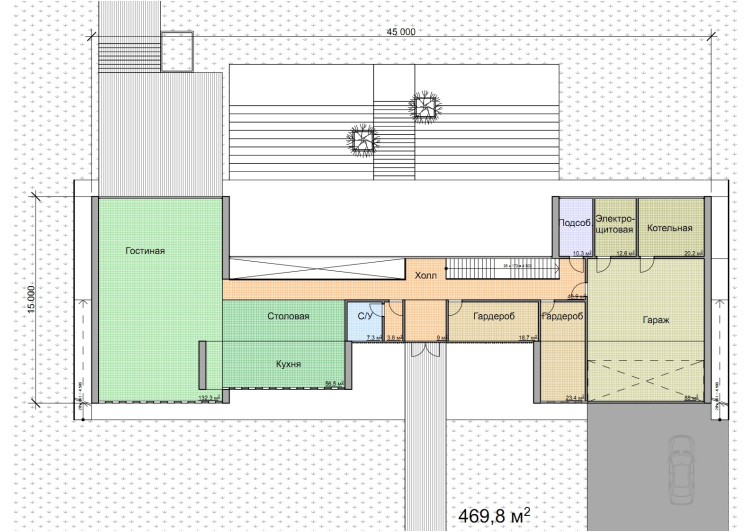

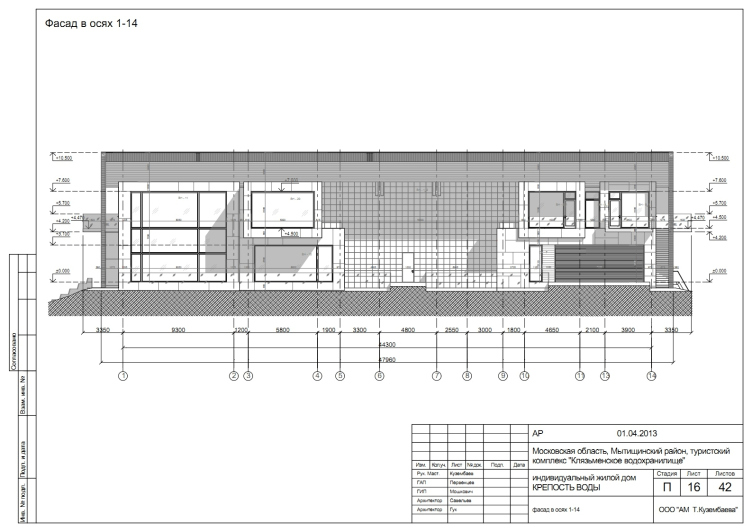

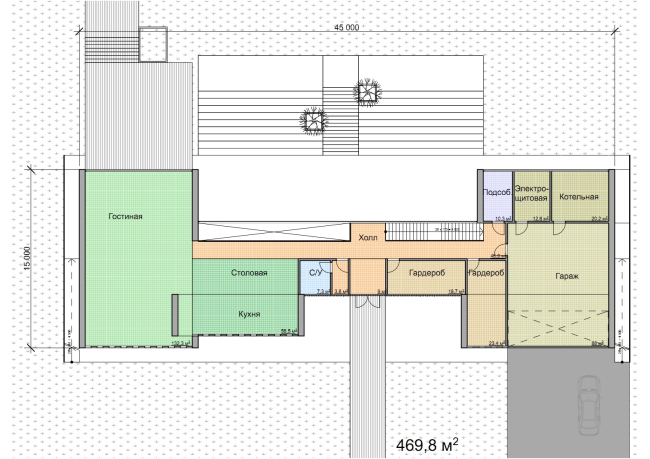

On the plan, the

house presents an elongated rectangle that occupies the allowed construction

spot almost to capacity. As the architect himself reminisces, had he left in

this place a parallelepiped of the required dimensions, this would have easily

yielded the customer the required number of square meters. But... A

straightforward parallelepiped in the reserve of Pirogovo? Or, parallelepiped

and Totan Kuzembaev, for that matter? An alliance like this is really hard to

see in one mind's eye - this is ultimately what architects are for - to create

buildings of a harmonious, yet non-trivial shape and plastic.

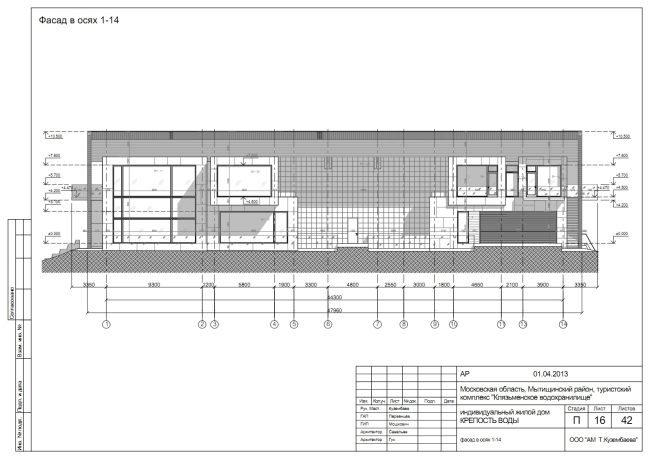

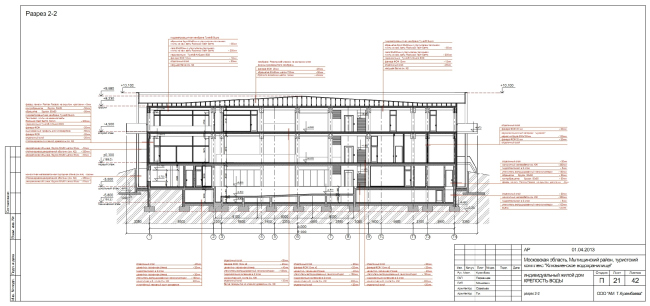

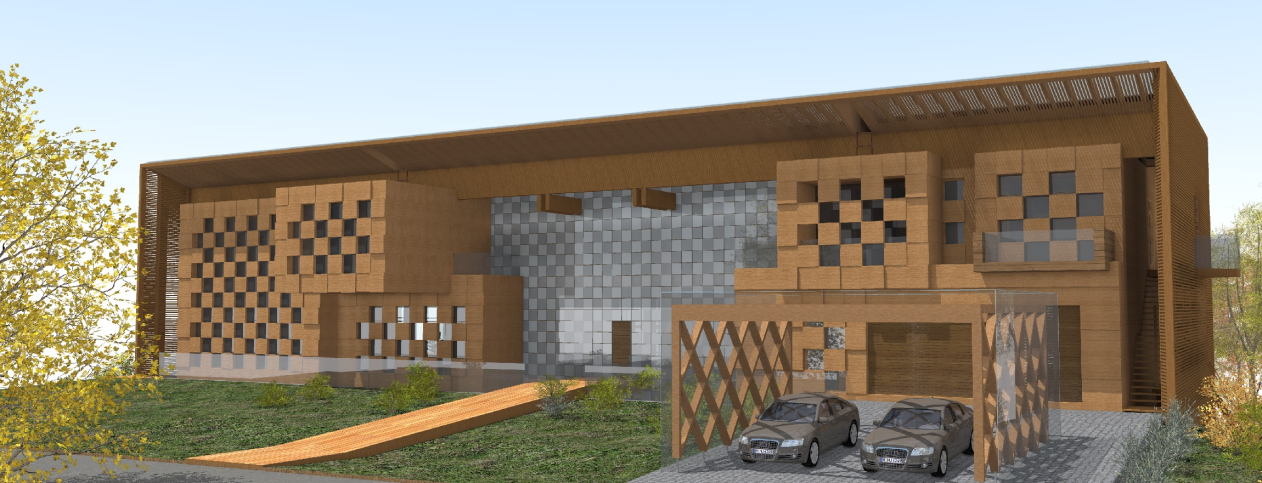

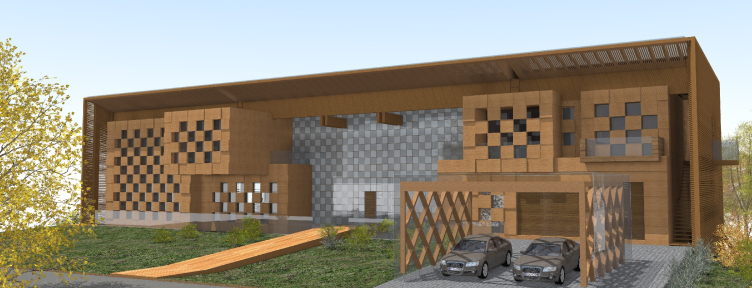

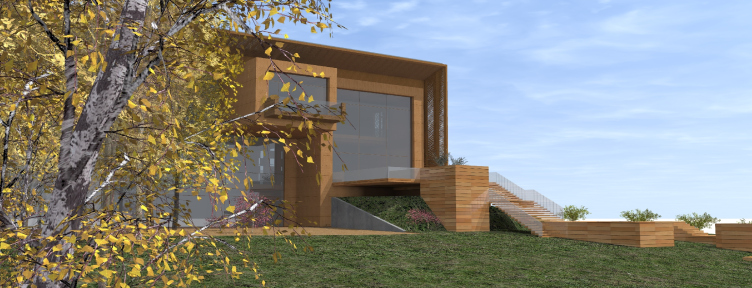

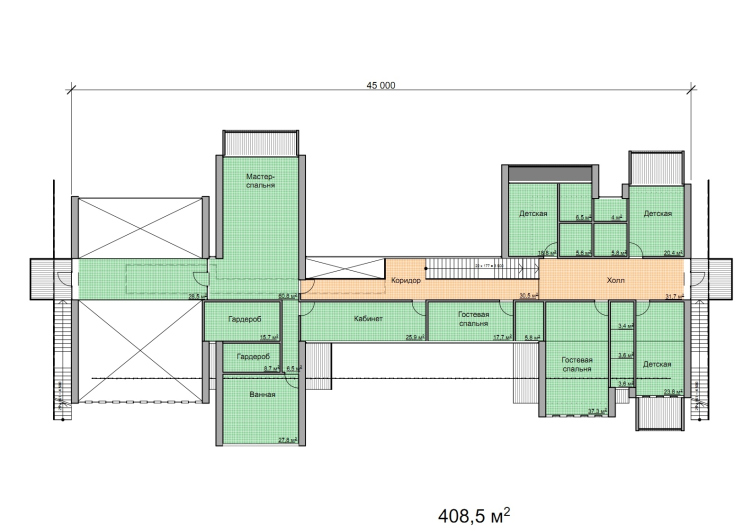

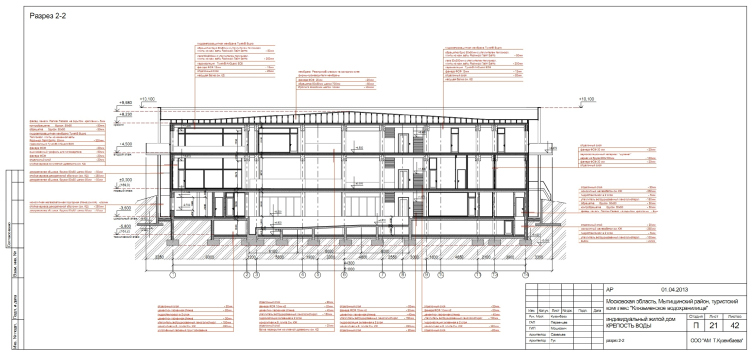

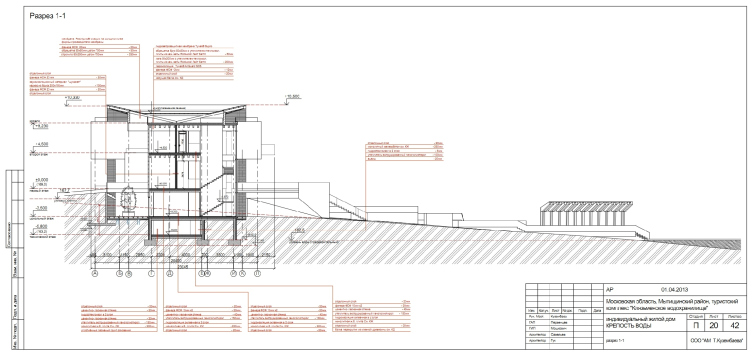

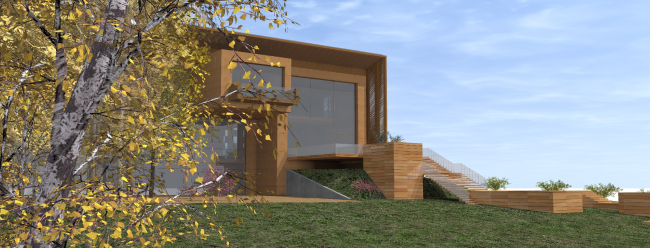

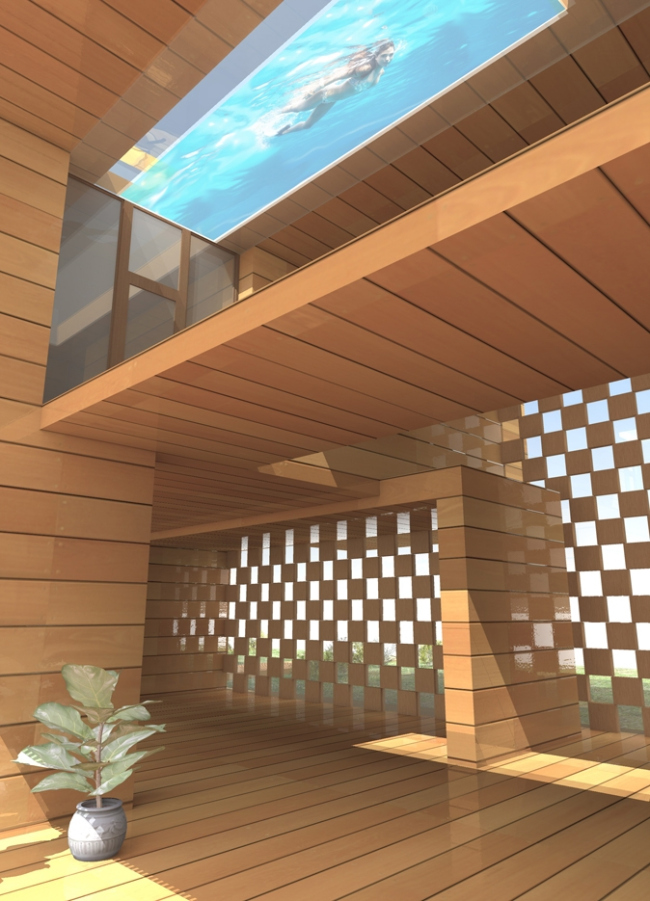

Besides the rather large square footage, the customer had a few other requirements for the future house. In particular, it was necessary to maximally "space apart" the "grown-up" and "children" zones and make the whole house as sunlit as possible. This made the architects use glass as one of the main facade materials, while the original parallelepiped shape was used to create two independent blocks tied into a single system. In fact, what Totan Kuzembaev does is leave only the outer shell of the parallelepiped, into which he "implants" a multitude of separate volumes. Visually, their independence is accentuated with the help of developed consoles - the "cubicles" of the separate premises, three in each wing, are placed with a perceptible shift to one another - while the space between the blocks is executed from glass. From the outer "frame", they are also separated visually - along the inner side walls of the parallelepiped, the architect runs open-air staircases, one of which provides a direct link between the garage and the second floor of the house, while the other, conversely, leads to the basement floor.

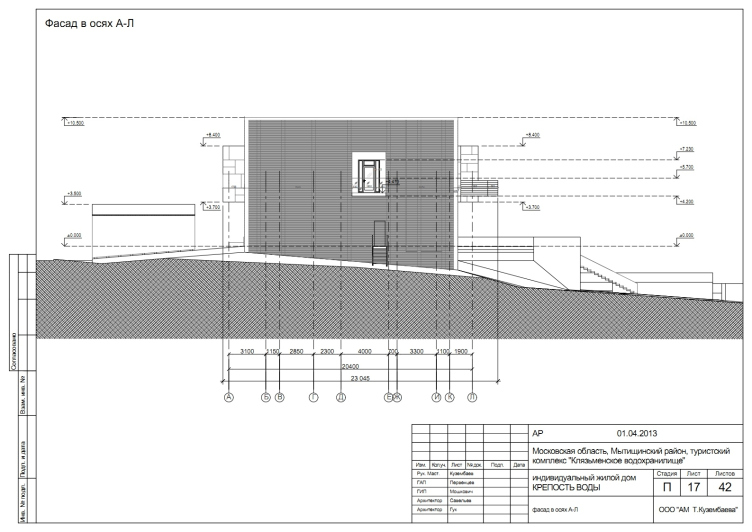

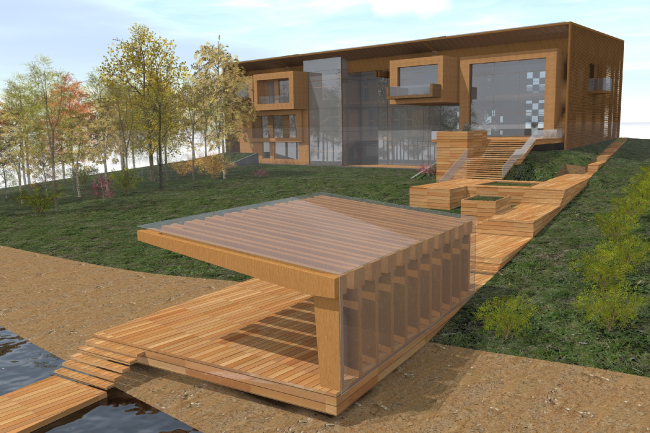

The feeling of the

entire structure being all too "massive" is also subdued by the moat

that surrounds the house, over which the architect throws a few bridges of

varying breadth. The moat also plays quite a down-to-earth part - it provides a

street access to all the premises of the basement floors which will enable the

serving personnel to get to them without having to enter the house. The

accumulation of water in it should be prevented by the roof pitch, while the people

going through it will be protected from the rain by the roof itself - the upper

crossbeam of the frame, though high-positioned, will serve as a safe awning

because of its sheer size.

As for the functional plan of the house, the architect fully meets the customer's requirement to provide the different generations of one family with as much independence as possible. In the left part of the building on the first floor there are the double-height living room and the kitchen/dining room, on the second floor - the masters' bedroom with closets and a bathroom; in the right part - a two-car garage and the maintenance rooms, above them - guest bedrooms and the masters' studies.

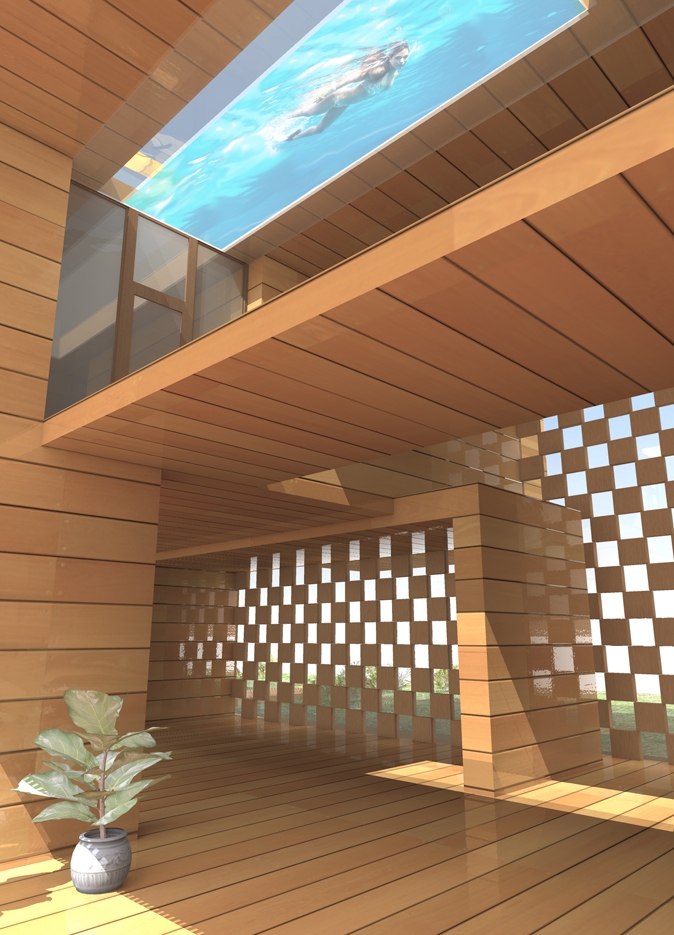

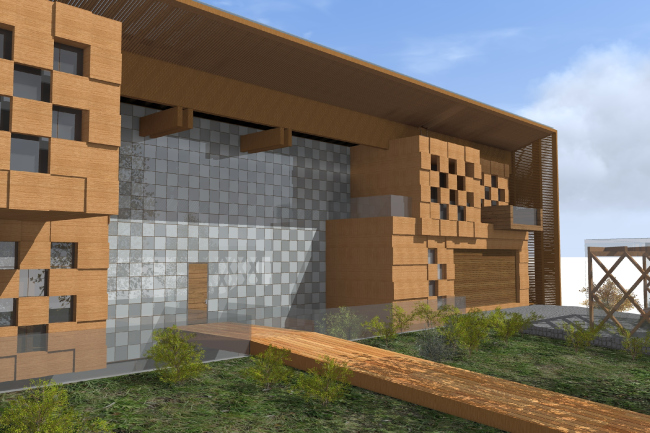

Initially, Totan

Kuzembaev planned to provide all the bedrooms with panoramic glass windows,

inserting a piece of stained glass into each of the cubicles - but the fair

proximity to the highway that the house commands en face, made the architect

find a more subtle facing solution for the main facade. The stained glass

pieces ultimately consist of glass and wooden squares alternating in a

staggered order, picking up and developing, on the micro-level, the theme of

the same-looking wooden consoles. And in the central art that is fully glazed,

the part of "black squares" is played by the opaque glass pieces that

create, on the one hand, let inside the house as much light as possible, and,

in the other hand, securely protect it from the prying eyes.

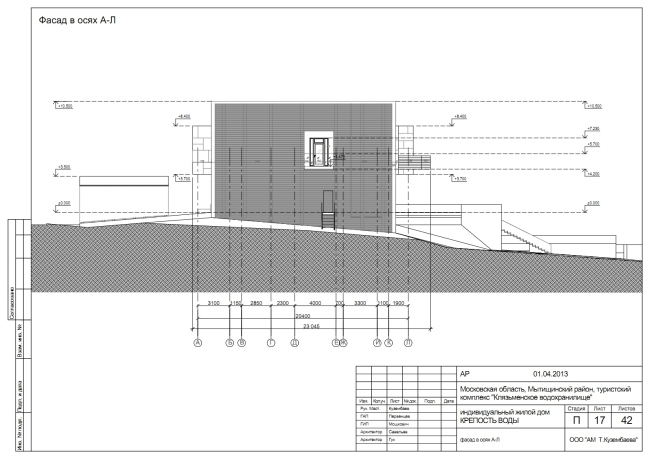

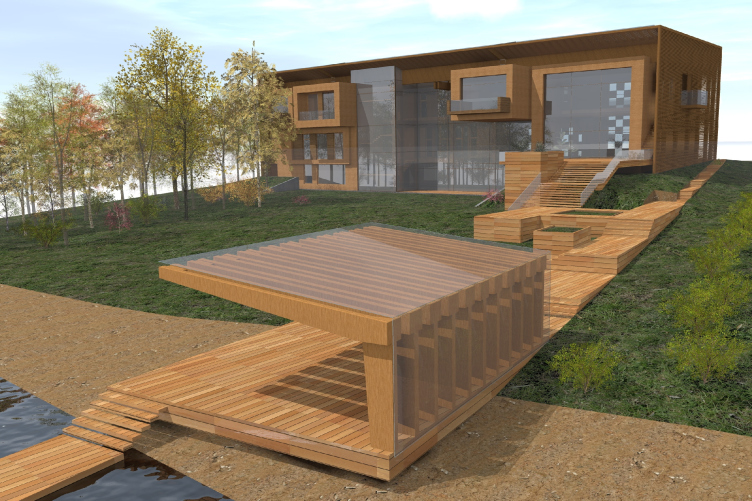

At the opposite

side of the house that commands the lake view, the situation is quite different

- here the transparent surfaces definitely prevail. Encased in exquisite wooden

frames, they reflect the surrounding landscape making the house look like a

gallery of ever-changing pictures of living nature. What is peculiar here is

the fact that the architect, at the expense of the height difference, was able

to fully expose the basement floor here - in the summertime its swimming pool

turns into an open-air one. Rooted in the landscape, the house continues in a

while series of open-air terraces cascading down to the water, and their

connecting stairways without any railings whatsoever.

One should say here that fences or railings of any kind are pretty much non-existent in this house. Of course, on the balconies of the second floor, on the porch, and above the moat, there are protective structures but they all are executed from heat-strengthened glass that the architect does not even frame with anything. The same transparent casing of the very same kind is used to cover the garage - its glass surfaces are barely discernible against the background of its wooden lath walls. Introducing such a huge quantity of glass into the project, and also, whenever possible, substituting the blind wooden surfaces with lathwork, Totan Kuzembaev not only achieves the effect of incredible visual lightness of this not-so-small house but also the unity of this complex composition. So it is for a good reason that the architect himself calls this house a "honeycomb" - assembled from separate "cells" it looks whole and self-sufficient.