Context

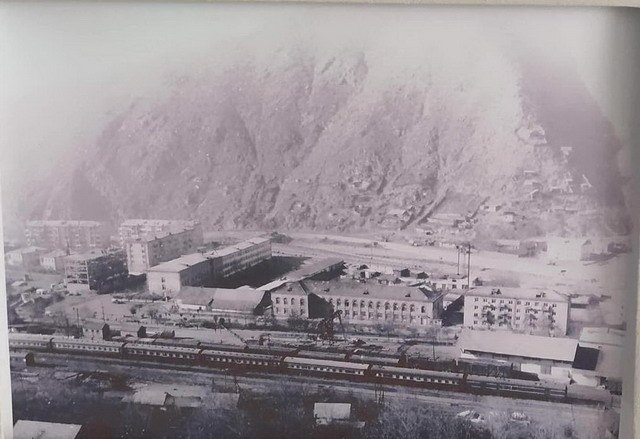

The station stands on a small hill in the heart of the city, with its main facade opening onto Stepan Shaumyan Street, which runs straight to the mountain ridge.

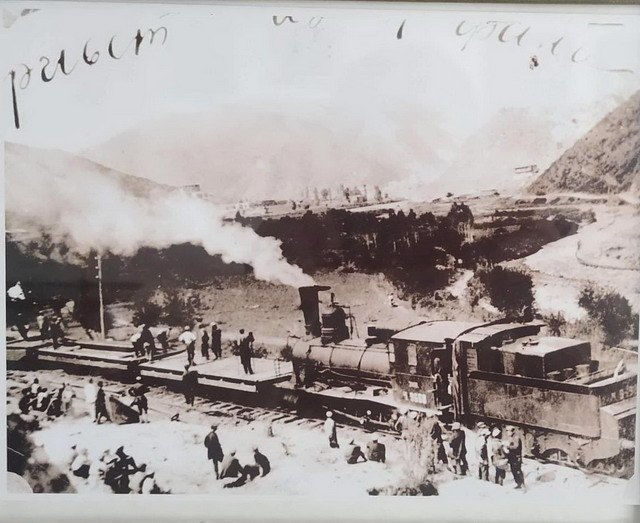

Kapan railway station before the reconstruction

© TUMO

Kapan departs from the rigid order of Soviet urban planning. Built into steep slopes and stretched along both banks of the Voghji River, the city follows an organic framework of its own.

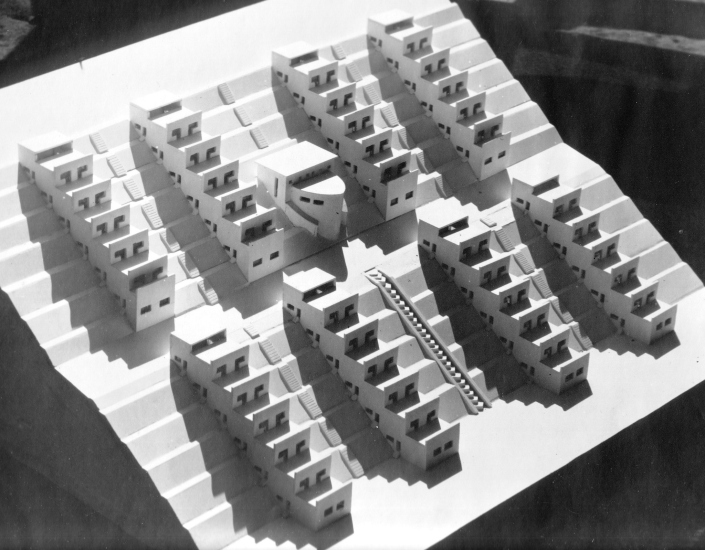

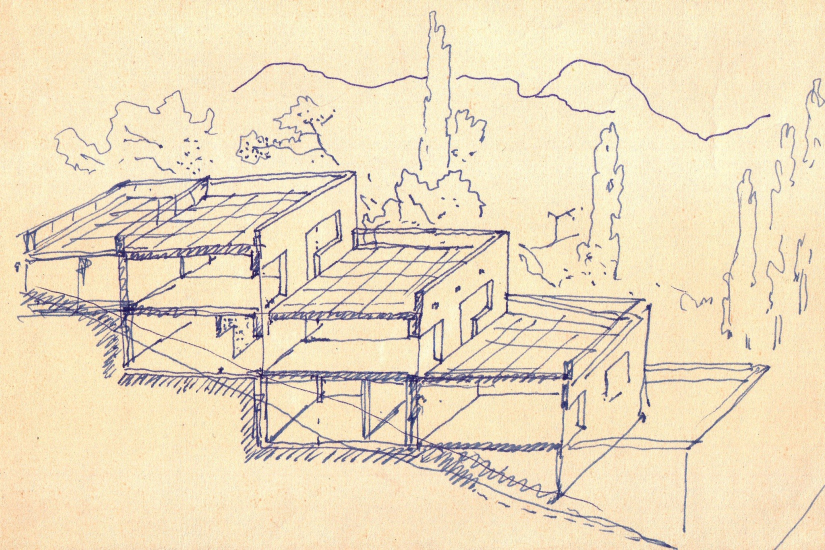

Nearby are landmarks spanning the Middle Ages to the early modern period: the 10th-century Vahanavank Monastery, the 10th–13th-century Kataravank Fortress, the 17th-century Halidzor Fortress, and the 18th-century Greek Orthodox Church of St. Catherine in the village of Kavart. Kapan is notable for another reason as well. In the late 1920s, the Constructivist architect Mikayel Mazmanyan designed a workers’ settlement with terraced housing that drew on the region’s traditional dwelling type. Decades later, his work became the prototype for a residential district in the Davit Bek neighborhood, realized in the late Soviet period.

Davit-Bek district in Kapan

Photographer: Syunik via Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

The building

The former station is a one-story, rectangular, and symmetrical building with a classic layout: a central vestibule flanked by two waiting halls. Constructed from pink tuff in the style of national neoclassicism, it features a projecting central pavilion defined by a large glazed arch. Extending out from the center, rectangular windows alternate with Ionic pilasters along the facade.

TUMO Kapan

© Normal Studio

Completed in 1932, the station served as Kapan’s main transportation hub until the opening of the airport in 1972. Rail service was suspended in the early 1990s due to military conflict, and the building stood abandoned for more than three decades, gradually deteriorating. Before TUMO took ownership, the property was held privately.

Reconstruction

Before the reconstruction, TUMO set up temporary TUMO Boxes next to the station to serve as a learning space. They are still in use today for workshops and learning labs.

TUMO Kapan

© Normal Studio

The renovation unfolded in stages. The first priority was emergency stabilization and structural reinforcement, carried out by TUMO’s design team in collaboration with local engineers. Once the building was secured, work shifted to adapting it for its new role as an educational center.

A new technical annex was also added beside the station, clad in embossed silver panels that make a sharp visual contrast with the historic structure.

Adaptation

The adaptation was entrusted to Normal Studio, a Paris-based firm known for product and industrial design. At first glance, the choice might seem unconventional, but it was intentional. TUMO wanted a team that could go beyond designing classrooms, one capable of prototyping, testing, and implementing innovations throughout the process.

Preserving the building’s architectural integrity was central to the project, so interventions were kept minimal to maintain continuity of tradition and authenticity of heritage. The designers approached the interior with restraint, while introducing bold accents that signal progress. The result balances respect for the past with a contemporary reinterpretation suited to a completely new function. As the designers explained, this contrast reflects the “living, developing nature of the building, embodying the idea that history never ends but is enriched with new narratives.”

The original layout, with load-bearing walls dividing the halls, was left intact. The interior was reimagined as open and dynamic, designed to encourage self-learning activities. A minimalist palette—white walls, light resin floors, and OSB (oriented strand board) paneling along the side roofs—provides a neutral backdrop for custom furniture and objects created by Normal Studio for TUMO Kapan, most painted in International Klein Blue (IKB), the ultramarine shade invented and patented by Yves Klein.

TUMO Kapan

© Normal Studio

The lobby now houses a reception desk and related functions. Decorative wall panels conceal the radiators, while the only surviving ceiling painting has been carefully preserved. A linear hexagonal chandelier draws the eye upward, and the former waiting halls have been reconfigured as self-learning spaces.

To the right of the entrance is a café and coworking area that opens onto a glazed enclosed porch. Its focal point is a long black table running nearly the entire length of the hall, lit from above by a cream-colored chandelier in a gabled silhouette. Sofas with partitions line the perimeter.

On the left, a more flexible self-study zone features furniture in varied shapes, colors, and arrangements, with window sills doubling as seating. At its center stands a blue cube that serves as storage for the café.

Outside, the grounds were redesigned with new stairs, geometric L-shaped benches, and linear street lamps, all painted in International Klein Blue.

What sets TUMO Kapan apart within the network of Armenian centers is that it is the first to repurpose an existing building while keeping its original form intact, without extensions or added floors. In a short time, it has become a gathering place for the city’s youth.

For more than three decades the station sat abandoned, once a symbol of Kapan’s prominence and its connection to the wider world. Now it has regained civic importance. No longer a transport hub, it has been reborn as a center for technology and learning, oriented toward the future and connected to the world beyond.