Exhibition “Dictionary of Modern Architecture”, timed to coincide with the 30th anniversary of AB ATRIUM

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

The essence of the exhibition is that, yes, it’s retrospective and celebratory, but not quite. ATRIUM has gone far beyond the bounds of the “traditional” company exhibition with a collection of architectural projects – and they’ve certainly succeeded. They’ve created a vibrant, cohesive, and sculptural exhibit in line with their constant pursuit of plastique form. “We’ve filled it not only with visual imagery but with meaning” – the architects emphasize.

The entire exhibition is titled “The Dictionary of Contemporary Architecture”, leading to a collection of around 30 terms that describe the components and qualitative characteristics of their own understanding of modern architecture. Each term is unpacked through an essay: “You’ll need at least an hour and a half to walk through and read everything”. The idea to reflect on the components and qualities of their architectural philosophy might have emerged either 10 or 30 years ago – perhaps even at the very beginning of their independent practice in 1994, when Vera Butko and Anton Nadtochy opened their own architectural firm. Nonetheless, the “dictionary” itself was written over the past six years in collaboration with Anton and his brother Sergey Nadtochy. Anton graduated from the Department of Theory and History of Soviet and Contemporary Foreign Architecture at MARHI, while Sergey studied in London at the Architectural Association School. As a result, the affirmations they created represent a fusion of various architectural discourses – at the very least, the Russian and Western ones.

At the entrance to the second floor of the exhibition, there is a manifesto presented in two versions: verbal and visual. The video, in fact, harks back to the “Arch Moscow 2012” festival, where ATRIUM participated in the “Complexity” project – which illustrates just how long this “dictionary” has been taking shape.

Our manifesto begins with words about space and speaks of architecture as a metaphysical process and a way of understanding the surrounding reality, as well as an art form, a language, a game, and a medium. These ideas run like a thread throughout the exhibition, they unfold like a red ribbon through the entire narrative. The manifesto is illustrated by a conceptual video, where all architectural forms emerge from chaos, which in reality is an organized structure of high complexity.

Ultimately, a unified field of meanings is created, describing the key qualities of contemporary architecture. We present our ontological perspective on architecture, in a sense.

Ultimately, a unified field of meanings is created, describing the key qualities of contemporary architecture. We present our ontological perspective on architecture, in a sense.

The dictionary is organized using the letters of the word ATRIUM, with each letter corresponding to a key concept, along with secondary terms, not subordinated by meaning but simply by the starting letter. Hence, it’s a dictionary. From the beginning to the end of the name, the number of subordinate words increases. For instance, M: morphology, movement, method, motto (that key phrase or statement), materiality, meta-formation. Sometimes, you can discern a message from the neighboring concepts, such as “re-thinking – radical”. As I mentioned earlier, it’s a game of playing with words within a dictionary.

Exhibition “Dictionary of Modern Architecture”, timed to coincide with the 30th anniversary of AB ATRIUM

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

However, there’s a bit of a stretch here. The dictionary doesn’t follow the entire alphabet – how is that? Is it only a part of the dictionary? There can be many answers, such as this: we’re looking at a dictionary specifically compiled by the architects of ATRIUM and exclusively focused on contemporary architecture – the authors have chosen the terms that suit their preferences. Another answer might be that if we start sorting through various phenomena, we can always find many different words under different letters to express the desired thought. If you spend that hour and a half wandering through the exhibition and reading everything, you’ll find that the vocabulary of a modern architect is indeed highly recognizable.

But there’s another thing that’s even more interesting.

Much has been said about whether architects write, whether they can write, and whether they even need to know how to write. Like any complex profession that requires talent and creative ability, architecture has been accompanied by texts since antiquity.

Moreover: “architects write differently, not like art historians or journalists” – emphasizes Anton Nadtochy.

Generally speaking, the subject of architects’ writings on architecture is vast and still waiting for its dedicated researcher. It would be a bit of a cliché to mention Vitruvius, but it seems that it all began with him – or almost with him. Often, texts by architects run parallel to, and diverge significantly from, the visual reality of the product they are creating. It might even seem that when architects start writing, they are trying to dodge the primary task. While in antiquity and the Renaissance, architects would frequently dive into descriptions of construction technology, today they lean more toward cultural studies, philosophy, and poetry. A manifesto, after all, is often poetry framed within philosophy. Thus, an architect’s text is, in many cases, an attempt to broaden the boundaries of the profession, complementing it through a cross-disciplinary method.

That being said, here we have a dictionary of concepts relevant to contemporary architecture, particularly close to ATRIUM. This dictionary is not just about representation, though that is certainly part of it – it’s also about self-reflection and analysis.

However! In general, it is quite normal for an exhibition to include words. At architectural exhibitions, these are often the data of specific projects and their descriptions, whereas at exhibitions where architects present themselves as contemporary artists, you’re more likely to encounter either manifestos or statements that are not immediately clear to everyone – a sort of “conceptualist gone wild” moment. Both approaches are familiar and well-known, but what does ATRIUM do? The architects make words an integral part of their exhibition, treating them as a formal element. First, they place them on rounded pink walls. Second, they make the words interact with the characteristic complex lines of their forms. Together, these lines, the vibrant pink signature color, and the words form a manifesto distributed across the space.

Exhibition “Dictionary of Modern Architecture”, timed to coincide with the 30th anniversary of AB ATRIUM

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

The words envelop the exhibition space, and the deliberate incompleteness of the list – linked to the company’s name – rhymes with the fact that we can’t explain the angle of every line in the wireframe-like graphic mesh. Similarly, the words can probably be seen as “flashes” or “glimpses” of something bigger – essentially what the ATRIUM architects have been working on their entire lives: “contemporary architecture”. I asked Anton Nadtochy when modern architecture began for ATRIUM, and he recalled the 2000 Venice Biennale, which took place under curator Massimiliano Fuksas’ motto: “More Ethics, Less Aesthetics”. However, in this context, I think the 2002 Biennale by Deyan Sudjic, with the theme “Next”, might be more fitting. That event seemed to showcase the phenomenon that later became known as neo-modernism and “starchitecture”, or nonlinear, or digital architecture. However, it’s clear that the roots of the movement to which ATRIUM’s works belong can be traced back to the early 2000s. “Twentieth-century architecture ended two hundred years ago!” Anton Nadtochy boldly declares. One could argue that it didn’t end THAT long ago – but the meaning of the statement is entirely clear.

The second key feature of ATRIUM’s manifesto exhibition, beyond its dictionary-like structure and spatial distribution, is its focus on form for form’s sake.

For 30 years, ATRIUM has been working on form, constantly searching for it. Form that’s complex. Form that’s paradoxical. Unpredictable and surprising. WOW-form. Sculptural, flexible. There’s another handful of words. Incidentally, “complexity” is also an important concept in this case – so it’s no coincidence that on the second floor, among other things, you can see the video of the “Complexity” project presented at Arch Moscow.

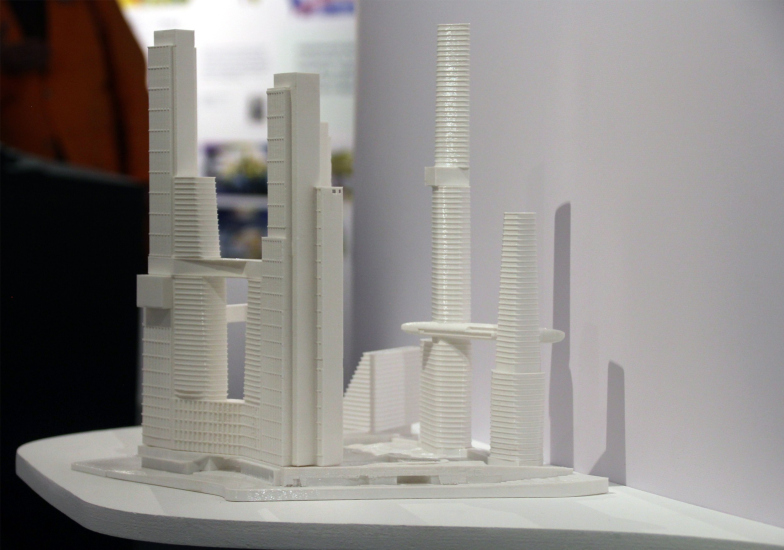

This is what form is about, says Sergey Nadtochy, standing next to the object created for the “Museum of Architecture” exhibition. The object consists of two cubes with very, very intricate cuts inside – or, perhaps, fused together from various volumes. There are two cubes because one is the inversion of the other: what’s a volume in one is void in the other, and vice versa. This is what a Museum of Architecture should be like! Just imagine the interior space! “We’ll definitely build it,” the architects conclude. And they clarify: “Back in the day, at VKhUTEMAS, such formal experiments were considered introductory studies, but now they are experiments on a whole new artistic and technological level”.

Exhibition “Dictionary of Modern Architecture”, timed to coincide with the 30th anniversary of ATRIUM

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

The essence of the search for form lies in the treatment of architecture as art. This is a very appealing and correct approach. Over the last quarter-century, following the rise of neo-modernism, the meaning of architecture has been sought in many things – ecology, identity, urban space – often carefully avoiding the primary task: the search for form. ATRIUM, however, purposefully focuses on form, openly declaring that architecture is, above all, an art form. Even in their entry for the letter “A”, they leave only one word: “art” – “architecture as art”.

The entire first floor is dedicated to art objects. Some of these are early works, dating back to 2017, while others were created specifically for this exhibition – and, as we remember, there’s even an object made for an upcoming exhibition.

Exhibition “Dictionary of Modern Architecture”, timed to coincide with the 30th anniversary of ATRIUM

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru

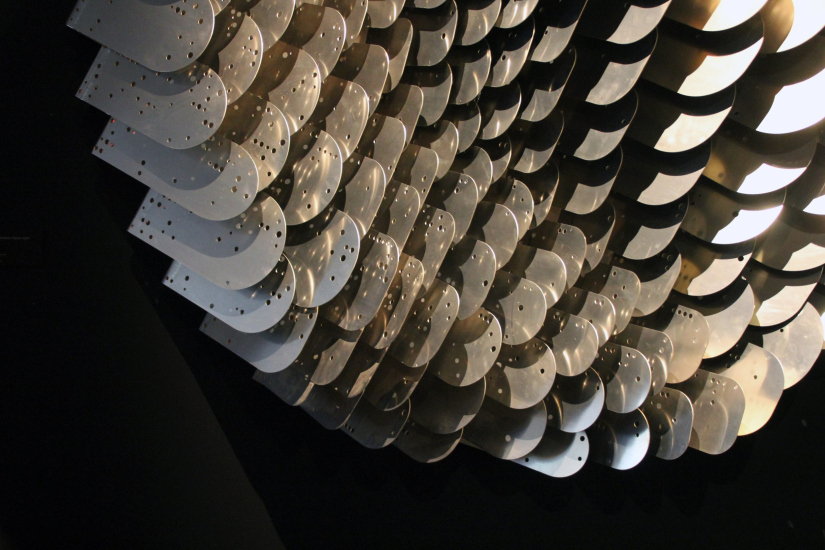

“Most of the art objects – Anton Nadtochy explains – Were designed using Grasshopper, based on its 3D models, with each element having a unique form. Some of the art objects were assembled using augmented reality”. Meanwhile, on a screen nearby, the assembly process of one of the objects is shown. It is an anodized gold structure: the person assembling it uses a tablet to view the outlines and number of each element, places the real fragment in position, checks it against the prototype, and fastens it in place. The process is indeed something worth seeing.

I ask, “And those reflections that your nonlinear gold pyramid casts on the window reveal – were they calculated as well?” “No,” he replies, “the reflections happened by chance. But they’re quite a sight to see too!”

“Our work on art objects is a process of form exploration, testing out solutions that we can later apply to ‘large-scale’ architecture,” Anton Nadtochy continues. “It’s easy and enjoyable to experiment with these, to develop a language that we can later use in projects of a larger scale”. At the same time, these art objects are design pieces that can be placed, for example, in the lobby of a residential building. ATRIUM has been working on producing its own industrial design objects for some time now, such as shelving units, which they further incorporate into their projects.

It’s important to emphasize that it’s not just about ventures into design. Everything shown at the exhibition – the displays, videos, objects, models, the computer game from the recent Arch Moscow exhibition, and even the showroom interior in the metaverse – was all created within the company, as ATRIUM is a full-cycle architectural firm, currently employing around 150 people.

Thus, I’d assume that the pursuit of form – complex, nonlinear, digital form, the kind of form that no one has yet conceived – can be understood as the core of Vera Butko and Anton Nadtochy’s architectural creativity. However, architecture is a multifaceted endeavor by nature, from the task itself to teamwork (which is also among the concepts) and the methods of implementation. So, around something that can be considered as “pure form” and “architecture as art”, various phenomena and ideas hover, attaching themselves to it more or less closely.

For example, cultural or natural identity, and the challenge of skyscraper design, solved in the format of a “vertical city”.

You see a lot of things here, and words become part of this intricately molded world, become a building material themselves, just as the architects’ research efforts are: in the pavilion dedicated to schools (yes, there is one!), you’ll find ATRIUM’s well-known book from last year, dedicated to educational spaces.

The “Dictionary” has also been published by Tatlin as the company’s anniversary book, embedding their projects into a narrative about the architectural fundamentals.

And there is more to come. Anton Nadtochy says that ATRIUM has plans for other exhibitions and other explorations. I fully believe it!

The exhibition is open until October 3.