I think it’s safe to say that the “Details” residential complex is the most interesting of the new projects in Maryino. At the very least, it draws inspiration from the drawings by Maurits Escher – an artist as fascinating as Giovanni Battista Piranesi, and one of the most captivating artists of the 20th century. For the architects, Maurits Escher is a treasure trove, as his works feature not only optical illusions and the transformation of mimetic figures into geometric ones but also, almost always, a plethora of staircases. It’s reminiscent of Hogwarts, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it was Maurits Escher who influenced the idea of the moving staircases in the magical school, just as gothic colleges and castles could have influenced the artist’s own spatial concepts.

Back to New Moscow, though! The architects illustrate their idea with Maurits Escher’s 1938 lithograph “Cycle”, where little figures run up and down a staircase, transforming into the floor pattern from which more figures emerge.

The “source of inspiration” engraving. “Details” housing complex

Copyright: © Ostozhenka Architects

This is a striking image of cyclicality. One is tempted to “ground” it somehow and interpret it as a metaphor for the infinite generation of public spaces, which aligns well with contemporary urban planning discourse – after all, these little figures in the drawings appear to be running along some kind of amphitheater.

But, of course, it’s not so much about the amphitheater, but rather, it’s about the concept of cyclicality itself. Given a large plot with demanding technical and economic parameters and requirements for sunlight exposure, the architects began to shape its volume not abstractly based on harmonious proportions – which would have been fine as well – but by rhythmically organizing their efforts around the central idea. And that’s always more interesting. Initially, a “node” appeared in the center of the site, but later it was replaced by an emptiness – an element to which Rais Baishev pays close attention. In this case, he cites Lao Tzu “Though clay is used to form a vase, in what there isn’t lies its use. Thus, by using what there is, one uses what there isn’t”.

In an ideal representation on the preliminary model of form exploration – an approach that Rais Baishev considers crucial – the building indeed transforms into a series of staircases leading up and down, converging on a central square where all four courtyards meet at the corners.

Looking at the photographs of the preliminary models, one can’t help but think, “This is truly Escher”.

Surrealism and spatial reflections rooted in probability theory, when applied to something as seemingly mundane as a residential complex, do two things: first, they shake things up, revitalizing everything; second, they create a certain magnetism, built on the simultaneous distance (what does Escher have in common with a residential complex?) and closeness of concepts: staircases are about space, and the architecture of a residential complex is also about space. This allows the authors to plant the “seed” of free creative thought within a standard task while adding an element of intrigue – so much so that the phrase “not like the others” in the brochure no longer seems like an exaggeration.

From this “seed” grows a beautiful, to the point of stunning, presentation of the idea: volumes of varying heights are illuminated by different colors and lights; there’s a tree on each terrace, and a large number of green planes. The romantic massing shows how the green surface rises from the ground with the roofs, and the volume is formed by these “columns” growing from the earth. This evokes memories of Minecraft and many other modern games where you have to hop from platform to platform, much like those little figures from 1938.

The complex indeed looks striking, sparking interest and even evoking dreams of an ideal city. The presentation of the idea feels like the next “step”, balancing between a print and a real-life project.

However, the idea didn’t just spring from Maurits Escher – rather, it found its way to him, discovering in his work an aesthetic and perhaps psychological support.

The project, as often happens with large residential complexes in Moscow, evolved rapidly, with numerous changes to the task made in the course of the process, demanding intense effort. “The deadlines were tight, the scope of work was large, and the brief changed more than once”, says the project leader, Rais Baishev. “That’s why we have an unusual team of about twenty participants. In my view, each participant is a co-author of this success”.

“Details” housing complex. The authors collective

Copyright: © Ostozhenka Architects

It’s not the first time I’ve heard stories about architects’ fast-paced work with many unknowns. True, this was common in Moscow before, but now it really seems to be becoming the norm. Why, for what reason? Nevertheless, we see that architects, in responding to market demands, have learned, among other things, to form “flying squads” and generally react quickly to the ever-changing rules of the game. Is this supposed to be conducive to any kind of creative work? Or maybe, on the contrary, such relentless pressure helps to mobilize all resources? The idea can indeed serve as an inner core.

However, the idea didn’t solely grow out of Maurits Escher’s metaphysical graphics. In my opinion, aside from the “master task” of interpreting the significant volume of sheer useful square footage, it stemmed from three things. First, the modern love for stepped “cutaways” – once nurtured by Moshe Safdie, later by MVRDV, but given the greatest boost by Bjarke Ingels. Now, they “march across Moscow”. Second, the terraces themselves; finally, their usefulness is recognized in Moscow. The third source lies in the fact that silhouettes of the same height – whether they are blocks or rows of towers – have become something that everyone seems to be sick and tired of.

Ostozhenka has long experimented with terraces – take, for example, the first phase of River Park (2013–2018) – and with various “cutouts” and “cutaways” in the volumes: just 10-15 years ago, these cutouts often looked like large “arches” or “inverted arches”, deep recesses at the tops of buildings. Alexander Skokan even wrote an article about “openings, voids, and holes”. In recent years, following trends, the openings have often acquired, instead of asymmetry, a certain regular step-like pattern. It seems that in “Details” we see exactly this: the search for an unobtrusive silhouette, a multi-height structure, and the alternation of elevations with pauses brought to some certain regularity. The pictures by Maurits Escher, who favored regularity alongside paradoxes – his engravings are “metaphysically” dense and stable, as if they strive to contain their own strangeness – quite resonate with such a solution. That is to say, the project incorporates the experience of deconstructing form, based on an almost 30-year tradition, but what makes this project different is the fact that the deconstruction is placed here within the framework of a modular structure.

The main module of the structure is a cube with sides of 4 to 5 floors, about 15 meters tall. This module allows for the formation of a confidently stepped silhouette. And since the building is large, the module does not dictate the form rigidly; there are steps of 3 floors as well, but it still sets the overall contour. The contour of the “cubes” is also outlined on the facades – by frames, with noticeable pauses between them, forming a cross-like grid. However, this occurs only in the main part of the complex, as the lower section, up to the 7th floor, is dominated by a “base” horizontal band with one drop that echoes the terrain’s height drop of about 7 meters.

It should be noted that the façade grid is formed here by white lattice bands, concealing the air conditioning units. This, like the steps, is a fairly new trend: rhythmically organizing “boxes” on the facades is no longer customary, and the bands divert attention from the purely pragmatic things – in this case, they confidently grid the mass with supergraphics that, as a reminder, help to express the idea of mega-stairs composed of mega-cubes and outline this graphic idea at some distance from the main plane, creating shadows. Moreover, this solution helps to make the base itself (composed of glass and gray-blue polished material) look less dominating by making the façade surface look more “layered”.

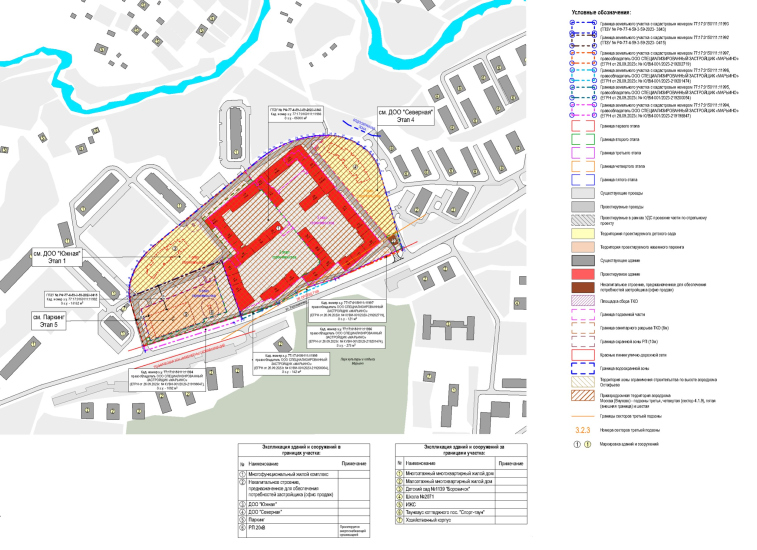

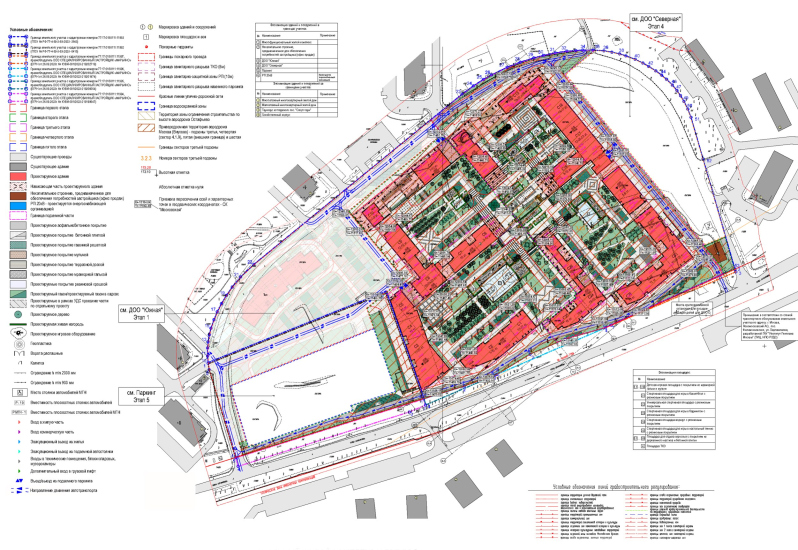

“Details” housing complex. (Stages 2, 3)

Copyright: © Ostozhenka Architects

The stepped silhouette design also works well in perspective – in some views, due to the descending levels, it seems as if the street “runs into the distance” faster than it normally would, which also contributes to the shaping of space and the lighting of the building’s silhouette.

The layout of the complex follows a block format, with an external contour of approximately 200 by 200 meters, similar to the large Stalinist blocks on Kutuzovsky Prospekt. Stalinist blocks were very large, and often something was built in the middle of their courtyards, whether a school, a local administration building, or simply another partitioning structure; this was a classic approach. The approach here is similar but, in part, paradoxically the opposite of the original idea: the inner buildings do not gravitate towards the center but instead recede from the outer buildings inward, leaving the middle empty. For Rais Baishev and the architects of Ostozhenka, this emptiness holds significant meaning. Here, it even becomes a kind of “homage to emptiness”, as all the inner buildings descend towards the center with their steps. The courtyards are marked out within a modern scale, smaller than “Stalinist” courtyards but larger than what was customary during historicism, ranging from 40 to 90 meters on one side, as seen in Level Prichalny, also designed by Ostozhenka.

Since the plot is not square, yet the “genetic code” of the concept is essentially based on squares, the idea adapts, showing flexibility: squares stretch into rectangles, as happens with some of the steps, and where the buildings come close to the road, creating a diagonal cut in the contour, they also receive a few cuts. Behind the outer buildings are a multi-story above-ground parking garage and two kindergartens, the “northern” and “southern”. These two kindergartens are no longer orthogonal – they are stretched along a curve and contextually echo the three-story houses that make up the surroundings of the complex.

There is also a large, striped, ribbed above-ground parking area. All the “auxiliary buildings”, it must be said, are designed succinctly, without any excessive decoration.

As for the format of the residential complex, aside from the idea of linking the building to the graphics of Maurits Escher, the building offers a “hybrid” block format. It is a block, but not quite. It is multi-height, but it is not a block with towers. Finally, strictly speaking, it is not a building with terraces either – the idea of green roofs had to be abandoned at the “dream-up” stage of the concept’s development. It would have been nice to keep it... but perhaps next time.

In the end, the building “plays” with modern and accessible formats of “cubes”. It mixes a variety of elements and brings them to its own unified denominator. This kind of play doesn’t result in a fundamental breakthrough, but it definitely wins you over due to its boldness in combining available resources with internally daring ideas. These ideas, embedded in the project from the earliest stages, are reflected in the facades and felt in the silhouette. The quarter with raised volumes became established in Moscow during the 2010’s. Here, we see a subtype: a whole complex based on uniform elevations – a “staircase” building.