The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

The wooden pavilion, which is oval in shape with round openings and skylights in the ceiling, was supervised by Anton Ladygin, and the project was implemented fairly quickly, within a year and a half. As for the Grotto, its restoration was curated by Nika Barinova-Malaya, which took four years (two years of design and two years of actual restoration work): not only because the Grotto had been in a dilapidated state for 20 years and was almost falling apart, but also because several discoveries were made during the process, and a few decisions were reasonably changed.

According to the architect, meetings with the client and the Department of Cultural Heritage were held almost on a weekly basis, and the restoration of the Grotto now required several times more effort and time than its construction did over a hundred years ago. In 2022, the completed project was awarded the “Moscow Restoration” prize.

How could such a small and seemingly simple, even somewhat untidy structure consume so much time and labor?

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

There is yet another circumstance that makes the Grotto remarkable. Its very existence in a small public park in the center of Moscow is somewhat atypical. Park grottoes have an impressive history, dating back to the Renaissance excavations of Roman palaces on the Palatine Hill. They pointed to the supposed antiquity of the places where they were situated, to the owner’s humanistic education, and even to their free-thinking attitude, as pagan deities often inhabited these grottoes. Not all grottoes are actually ruins, but by the 19th century, the typology of the ruined grotto had become dominant, and the one we are speaking about is precisely such a case, inviting romantic contemplation. Such grottoes are widespread in private parks belonging to estates or even palaces.

In public parks, grottos are less common and serve more as monuments, such as the Grotto in the Alexander Garden, which was designed as a monument to the victory over Napoleon and is therefore built from fragments of houses destroyed during the Great Fire of Moscow. Unlike most estate grottoes, it is adorned with an impressive Doric portico and has a sightseeing platform at the top, which integrates the grotto into the active life of the garden. Generally, public gardens, especially in the form in which they were formed in the 19th century and developed in the 20th, differ from estate parks in that practically every undertaking in them must be beneficial and adapted mainly for the entertainment of large crowds of people. An “estate” park, on the other hand, allows for solitary contemplation, while a public, urban park does not. Only recently, in the hipster post-industrial society, ideas for places of contemplation, including grottoes in public parks, have appeared without any additional monument function (see, for example, the Studio 44 and WEST 8 collaboration project for Tuchkov Buyan).

This is a long story that deserves special attention, but it concerns us because the story of the Grotto in the Bauman Garden is quite paradoxical. It is well presented here, but we will also briefly mention it in this article.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

At the very end of the 19th century, the architect Mikhail Bugrovsky built a neoclassical palace for the gold industrialist Nikolai Stakheev on Novaya Basmannaya Street. On the street side, there was a small regular garden, and on the inside, there was a landscape garden. Inside of it, probably, as Nika Barinova-Malaya suggests, a small grotto was built using the leftover stones from the construction: they utilized the remnants of production and joined the typology of the nobleman’s park. On the other hand, since Stakheev traded not only in gold but also in building materials, the grotto near the palace could have been another example of their use.

After the October Revolution, the mansion was nationalized, and the rear side part of the park was annexed to the public garden that had existed here since the end of the 18th century in place of the Golitsyn Park. In 1920, both parks opened simultaneously under the revolutionary name of the May 1 Garden, and in 1922 it was renamed as the Bauman Garden. Thus, the public garden received a grotto that was anything but typical for it. Predictably, they began to rebuild and adapt it to the needs of the strolling population.

During Soviet times, two sloping staircases were built from the public garden to the sightseeing platform at the top of the hill, into which the grotto is dug – they connected the platform to the park and complemented the historical staircases on either side of the entrance.

The main thing, however, is that a café was made inside, which later became a kebab restaurant, and still a little later, a beer house: the latter is especially well remembered and lamented by the old-timers. For the public catering enterprise, a miniature kitchen space with brick walls and beams made of metal channels was attached inside, on the side of the hill.

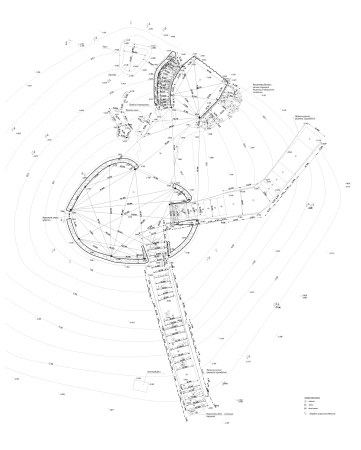

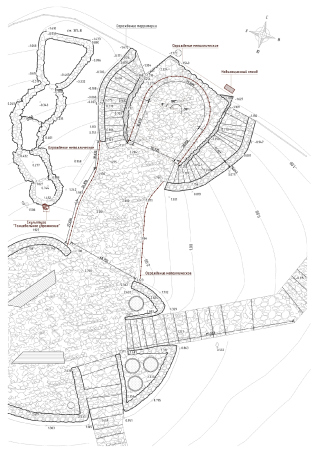

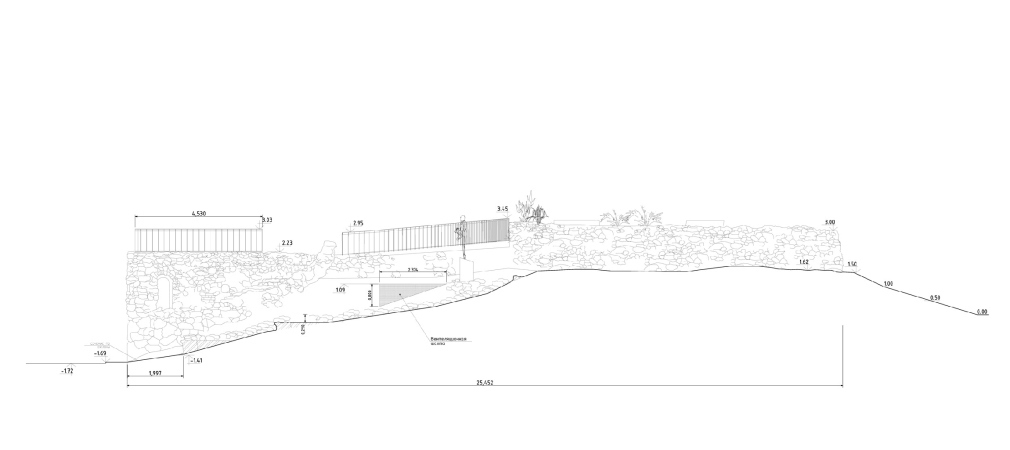

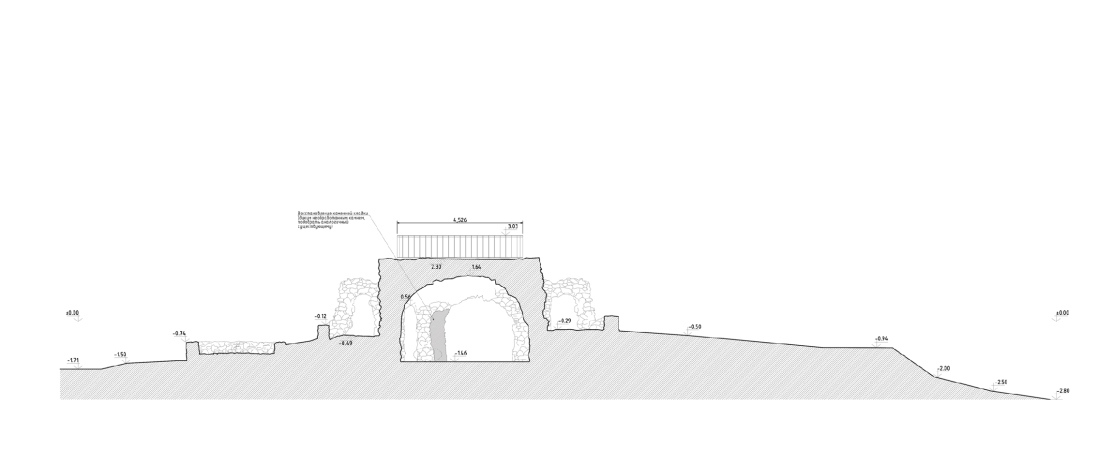

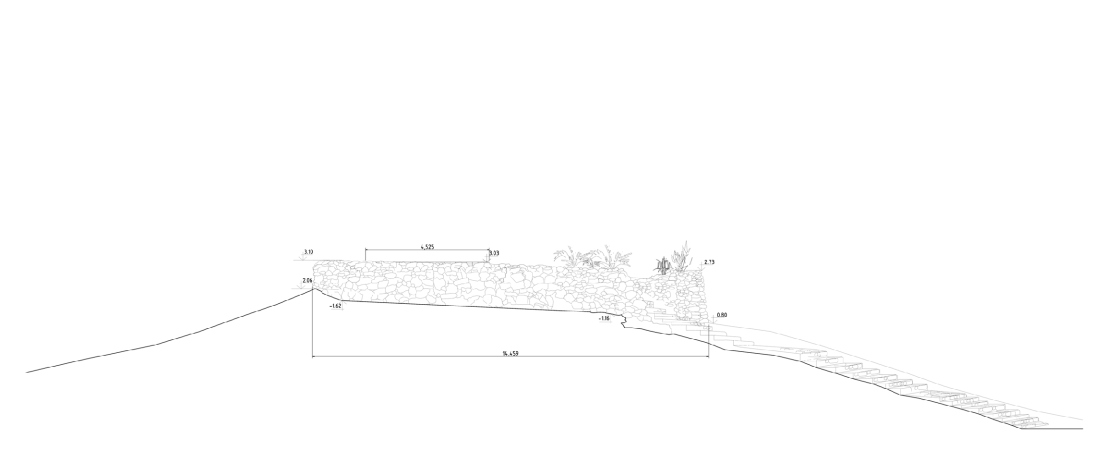

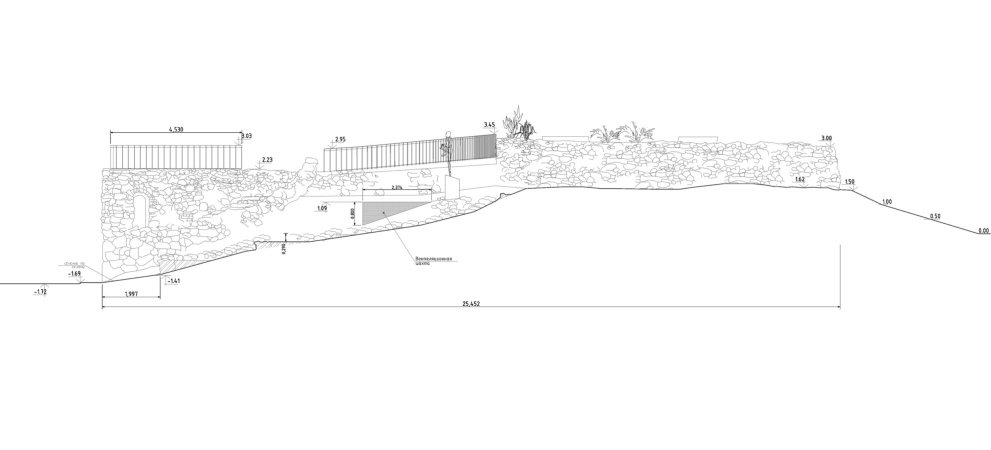

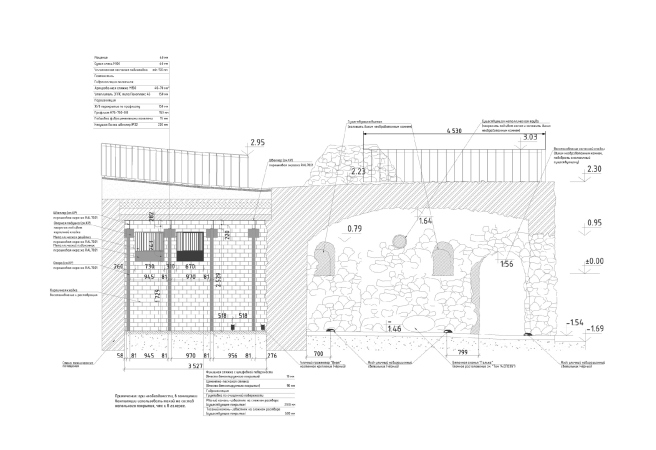

Section view 1-1. The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright © “People′s Architect”

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

In other words, about half of the complex appeared in Soviet times to cater for the needs of the strolling public, and was a result of adaptation to a new function.

Then, sometime in the 1990s, the beer house was shut down, the grotto began to deteriorate and stood behind a fence with a lonely look. At some point, the cascade fountain on the north slope broke down, the sculpture of a girl with a jug on top of the cascade disappeared, and the cascade itself was considered partially lost. The support in front of the northeast staircase collapsed, as partly did the ceiling of the Soviet cafeteria. Nika Barinova-Malaya remembers that on the first inspections, she was the only one daring to enter inside, as the construction seemed about to collapse.

The most significant discovery turned out to be the cascade, which was preserved almost entirely under layers, with a concrete bed that provided waterproofing. The pair of tubes that conveyed water from step to step also survived and is there to be seen.

As a result, two things happened: first, additional archaeological excavations had to be carried out, which took time, but allowed the fountain and its underground bed to be studied. Second, the plans to restore the function of the cascade, i.e. to let water flow through it, had to be abandoned – as this would require the destruction of the remains of the old fountain, which is under protection (the entire grotto is a heritage site of federal significance). The old water lifting mechanism did not survive, and the new one cannot be used, as the water would destroy the remains of the concrete bed, which have already been studied by archaeologists and put under protection. The cascade was restored as a decorative element: protective stone walls were built on top of it (as restorers do when preserving a historical foundation – they lay stones on top). And thus, picturesque “dry ponds” were created on the slope.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

Above them, there is a sculpture, which has a backstory of its own.

According to the description of the Cultural Heritage Department, the grotto included a sculpture of a girl carrying a jug. It has been irretrievably lost, and there are no photographs or descriptions of it, but it needed to be restored, as it was part of the Cultural Heritage Site. “We studied the modern market for girls with jugs, and it turned out to be completely depressing” – admits Nika Barinova-Malaya. The architects searched for a replacement, offered several options of other sculptural girls to the customers and the supervising organization to choose from, and they admit that they are glad that everyone settled for the idea that the architects liked the most – a copy of Auguste Rodin’s statuette “Dance Movement”.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

They chose Rodin as a representative of the same generation on the cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries, and the statue as a relatively unknown work. Moreover, they enlarged and replicated the small sculpture prototype, which was about 15 cm in size. Now it stands like a kind of nail, the base for the composition of a former fountain that has lost its functional meaning. It is likely that without the sculpture, the “dry” cascade would be completely unclear to a viewer who does not know its full backstory.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

So, the Grotto is a cultural heritage site, and its preservation includes, among other things, preserving the dimensions that were recorded during the restoration. Therefore, the architects kept the Soviet-era paths on the hill and the kitchen area inside. However, they replaced the concrete slabs on the paths and stairs with stone, and rebuilt the walls and ceiling of the former kitchen area. Initially, cheap Soviet bricks were used here, but now the architects, or rather the contractors, the builders of the company Archindustry, went to St. Petersburg, picked out and bought historic bricks for secondary use, to make the interior walls look more dignified.

The wall of the former kitchen. The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Julia tarabarina, Archi.ru

No one, except those who have read articles about the grotto or those who remember the beer house, would guess that there used to be a kitchen here – its inner brick “appendix” currently houses a video installation screen, specially mounted for the Grotto. The entrance arch has chamfers made of frosted polished steel, and an anti-vandal polycarbonate hood is placed in front of the monitor. Therefore, the micro-space did not even need to be closed with a door. From a distance, it glitters very attractively, inviting visitors inside.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

The cave of the grotto itself has been restored, with two innovations in its domed space: a stone floor and two stone seats in the form of terrazzo pebbles, which fit in quite nicely. They provide a place to sit without cluttering the space and are in line with the theme of the grotto, but their modern origins are also noticeable.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

The additions proposed by the architects mainly relate to landscaping: black lantern panels with milk-colored light on the sides of the stairs, simple concrete flower beds, trash cans, and wooden benches. Everything is in small quantities and very straightforward. There is also a prismatic block of information plaque to the left of the entrance, made of concrete but faced with travertine, which resembles another solution by the “People’s Architect”, the concrete houses with infographics in the Gorky Park’s playground.

The landscaping elements are not the main achievement of this project: they are simple and necessary, that’s all.

The main efforts were devoted to the restoration itself, which first required frequent supervision and second, new solutions that popped up during the work. On either side of the entrance to the grotto, there are two staircases leading to the top of the hill, with entrances framed by arches made of rough stone. The left, eastern arch was completely lost and had to be reconstructed, while the right was rebuilt with partly destroyed archivolts of the entrance restored by introducing new stones into the masonry. The metal beam above the entrance arch was preserved, and no new metal fasteners were introduced, staying within the framework of the stonework.

To the left, next to the information plaque – the restored left arch. The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

The volume of “wild” stones eventually turned out to be quite large, and the authors had to balance between the visibility of the inserts and the integrity of the masonry, which is exactly what the Venice Charter requires (see Clause 12).

Nika barinova-malaya, People′s Architect

In our country, it’s no longer common to build “pseudo” buildings, but many still have a soft spot for careful and cleaner solutions. Working with the Grotto, however, we made every effort to preserve the feeling of authenticity and antiquity. We didn’t cover up the textures, we didn’t add anything unnecessary, and we stayed within the framework of restoration, which was required by the status of this project, and its original character as an artificial park ruin. I think we managed to preserve the “face” and character of the Grotto, while giving it a new life at the same time.

I have a very personal relationship with the Grotto. I feel it like a living being: when I first came here, it was as if it was dying, I was afraid that we wouldn’t make it, it wouldn’t survive, that it would collapse. The process of restoration is similar to healing: as if you’re saving the life of a strange but interesting creature that, despite everything, wants to live. In four years of such salvation, I have, of course, become very close to the Grotto and was glad to see many people at the opening in the summer and hear mainly positive feedback.

I have a very personal relationship with the Grotto. I feel it like a living being: when I first came here, it was as if it was dying, I was afraid that we wouldn’t make it, it wouldn’t survive, that it would collapse. The process of restoration is similar to healing: as if you’re saving the life of a strange but interesting creature that, despite everything, wants to live. In four years of such salvation, I have, of course, become very close to the Grotto and was glad to see many people at the opening in the summer and hear mainly positive feedback.

The grotto has indeed become a living part of the park: people constantly climb up the hill and go inside, attracted by the flicker of the screen. I personally saw a guided tour in front of the grotto, probably not the only one.

Another interesting topic is the re-dating. In the documents of the State Inspectorate for the Protection of Monuments, the grotto was listed as a monument of the late 18th century. Studying the materials of the project, the architects established that the appearance of the grotto 200 years ago is very unlikely, and proved to experts that the building belongs to the turn of the 19th-20th centuries and to the Stakheev estate (see above). Now, the protective documents indicate a double date, perhaps waiting for its researcher.

As part of the client’s brief, the Bauman Garden management required ensuring safety. Thus, white lattice fences appeared in the project to enclose the observation platform at the top of the hill.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

A little later, again, for the same safety reasons, fences appeared at the bottom of the hill, also white, but of a lower height, and accompanied by signs that climbing the hill is prohibited. The task is to eliminate any hazards for peoples. The thing is, the Grotto hill has long been popular with local children for sledding. The park is small, and while sledding, children can bump into someone. To avoid injuries, the management strives to limit uncontrolled activity, which is definitely sad, as we are constantly balancing between activity and safety. The fences are a nuisance, to be quite honest.

However, since the architects didn’t really have a choice, they tried to make the fences light, bright, and custom-designed – with a broken rhythm.

However, one still hopes to someday get rid of the fences, as well as of the novelties that the Grotto has acquired in the last six months, which were not in the original plan or at the time of its opening: a XIX-century-style clock on the hill and a lamp accidentally stuck in the slope in the northern part...

Nevertheless, the Grotto is now fortified, and is definitely not in danger of collapse. It has been cleaned up and opened for visits and observation, which is an undeniable plus of four years of painstaking work on the heritage monument.

The grotto of the XIX century in Moscow′s Bauman Garden. Restoration 2018-2022

Copyright: Photo © Arseniy Rossikhin / provided by “People′s Architect”

There is another plus, in my opinion. Having made a leap from the romantic estate typology to the socialist reality in the form of a beer house, which old-timers nostalgically recall, the Grotto has now adapted to the reality of another, post-industrial, not to say hipster, era. It has regained some degree of disinterested contemplation, an activity not so focused on the material side of existence, like eating sausages in a beer house.

It is unknown what will happen to this small and not very ancient object in the future, but there is a certain historical justice in its new transformation.