"Skalisty Bereg« (»Rocky Shore") winery

Copyright: Photograph © Daniil Anneknov / Provided by Severin Project

In 2021, the winery building got an award at the “Golden Section” architectural show and was shortlisted at one of the largest architectural competitions, WAF.

As for WAF, we didn’t even hope to get that far. Global design companies with such well-known projects as, for example, an incinerator with a ski slope starting on its roof in Denmark, competed with us in the nomination “Production, energy, processing”. I consider our getting into the WAF finals, and even in the nomination where implemented projects compete, for that matter, to be a serious achievement by any standards.

“Skalisty Bereg” is a gravity-flow winery; grape juice and wort move here under the influence of gravity, the mechanical impact on them is minimized, which allows you to preserve the features of the terroir as much as possible – the sum of these features is what determines the specifics of the wine, and upon this set of features the whole value of the ”protected geographical origin” is based. The location of the building on the 32-hectare land site was proposed to the client by Alexander Balabin; the 10-meter height difference of the construction site made it possible to make a gravity-flow winery; the operated roof commands sweeping sea views between the hills.

The building contains the entire technological chain: production, storing wine in casks and bottling it, as well as a restaurant, a tasting room and an observation deck. The winery building provides a lot of space for exhibitions and wine conventions.

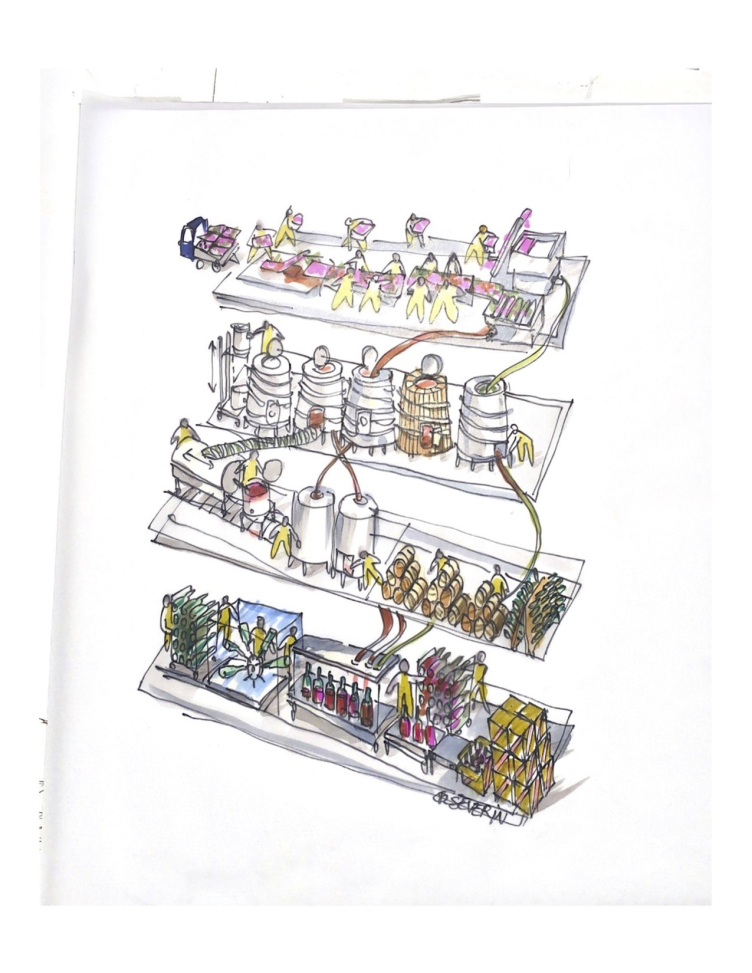

Alexander Balabin made a clear flowchart showing the entire cycle of wine production and storage with the functions distributed over the floors.

The flowchart of the gravity-flow winemaking

Copyright: © Alexander Balabin

In the movie “A Good Year”, Uncle Henry Skinner, the vineyard owner, says the famous quote: “I enjoy making wine, because this sublime nectar is quite simply incapable of lying. Picked too early, picked too late, it matters not – the wine will always whisper into your mouth with complete, unabashed honesty every time you take a sip.” These properties of wine generated the idea of the “Skalisty Bereg” winery.

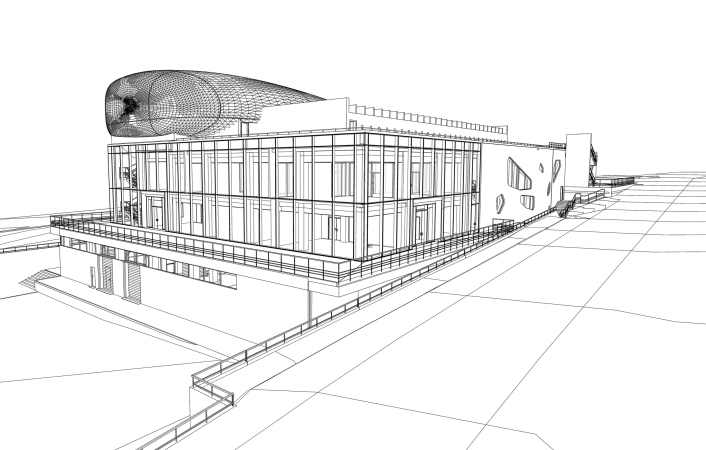

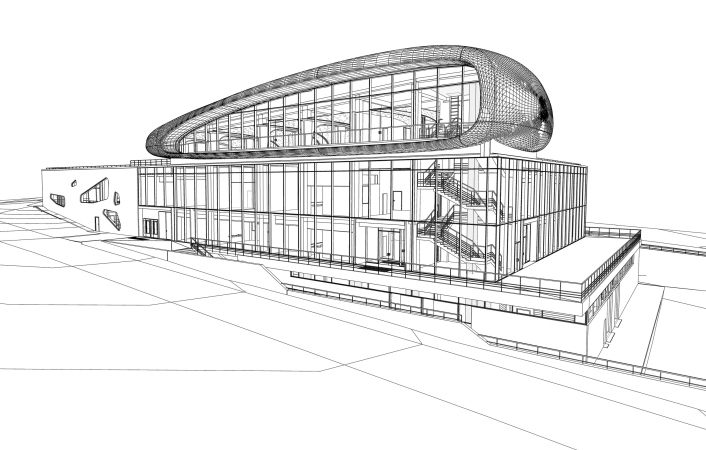

Looking at the building created by Alexander Balabin, one can clearly see two parts in it: an orthogonal brutal three-story production building from glass and exposed concrete, partially buried in the hill, and the top elliptical-shaped volume of the tasting room that looks like a giant sea pebble. “Wine is an absolutely natural product, which only gets better with age, and exposed concrete is quite a match for it because this is an honest and natural material” the architect says. The art of winemaking is hard manual work that is done 365 days a year, and it is reflected in the main orthogonal building that includes production facilities, wine storage, and the offices. Wine tasting is a sensual enjoyment, and for this the architect designed a tasting room contained in a smooth white ellipse commanding the sea view. From the room, one can exit to the roof of the main building.

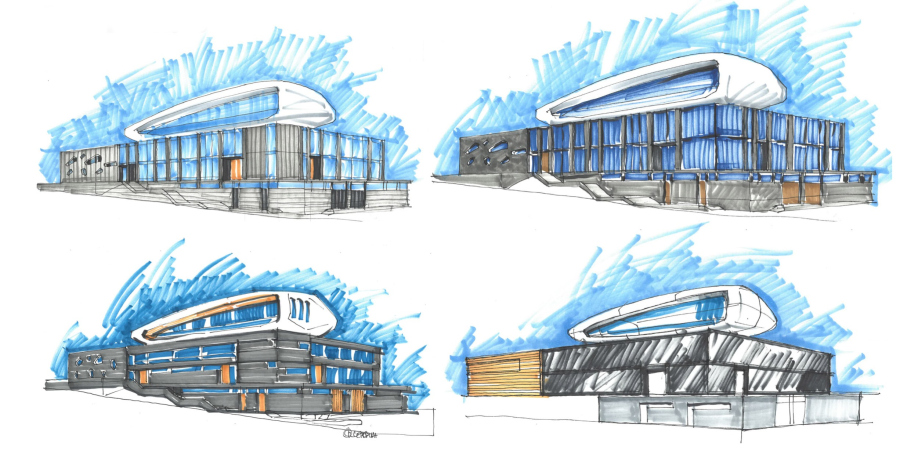

The backstory of the project goes like this. In 2017, the client approached Alexander Balabin with a pragmatic task: he needed a simple technological facility built from quick-mount structures. However, in the process of the work the building changed, and it became clear that architecture was needed. Alexander came up with several options.

The first one was called “Tuscan” and was designed in a generalized style of architecture of early Renaissance; the second one was called “Bauhaus”, the third “Carlo Scarpa”, in the spirit of the famous Italian master of the 20th century, and the fourth looked more technology-based, like a Swiss factory. And there was also a fifth variant, the most expressive one, which Alexander Balabin drew just for his own intellectual enjoyment. As is usually the case, this was the one that got picked.

The resulting building keeps up the straightforwardness and lightness of an artist’s casual stroke, inspired by the sea, the sky, and the breathing of the landscape as the artist tried to capture genius loci. The “pebble” looks as if it somewhat sloppily lies on the roof of the building, overhanging a bit like a cantilever. The main three bottom tiers are executed in concrete, but the second and third floors, where people sit, have glass facades. Thus, it looks as if the “pebble” rests on a glass volume that reflects the sky, i.e. is sandwiched between the “sky” and real sky, at the same time maintaining visual contact with the sea.

“Rocky Shore” winery

Copyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project

On the whole, the tectonics of the building is rather sharp. Not only the “pebble” hovers above the ground, visually resting just on the lightweight glass tier, but also the platform with a cantilevered ledge between the first and second floor lies on a ribbon window, i.e. again almost on nothing. The entrances to the building, slightly sunken in, almost merge with the glass facade, without violating the composition of vivid horizontals. To the left of the winery, there is a main staircase spanning several floors.

Unlike the glass office part, the production part of the third tier, where the grapes are loaded, is executed in concrete with dramatic openings in the shape of pebbles of larger and smaller sizes. Thus the main theme of the sea pebble is developed in individual motifs as well. Through these windows and through the glass facades, the winery is connected with the surroundings, and there are also technical windows inside, so, when walking along the corridor, a person can look into the technology-based production facilities and admire the scenery at the same time.

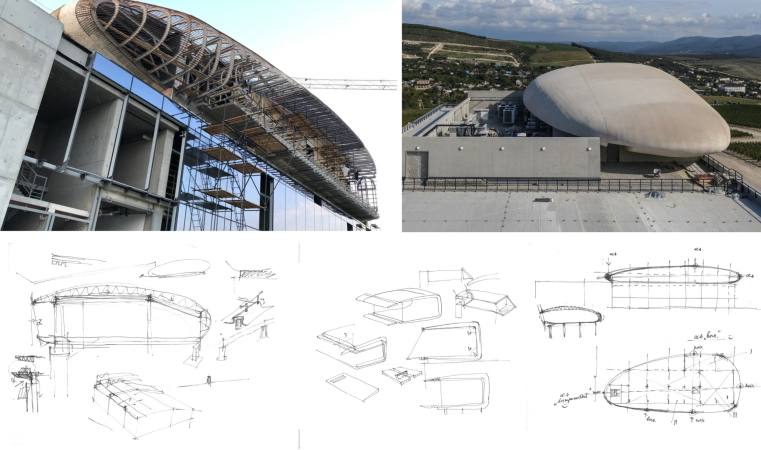

In order to make all this a reality, Alexander Balabin and his partners had to cope with formidable technological challenges. The technology of applying fiberglass concrete to an elliptical metal structure is quite new for Russia. The coverage of the “pebble” was designed by Andrey Poletaev and the “Arkhitektura Blagopoluchiya” (“Architecture of Well-being”) group in cooperation with OOO MRG Stroy/Soldisgroup, which did the curvilinear pavilions in the Zaryadye Park, as well as the Zaha Hadid office building on the Sharikopodshipnikovaya Street.

Working with exposed concrete was just as challenging but the result was well worth it. Many architects love exposed concrete for its honesty, masculinity, and longevity. From the side of Alexander Balabin, this was also homage to Tadao Ando. The walls of the winery have three plies in them. The inner ply (200mm) and the outer ply (100mn) are exposed concrete without any decor, with a 100mm of heat retaining material sandwiched between them. The only decor on the concrete wall is holes, traces of formwork fastening, and seams.

“The building of the winery was built of monolithic reinforced concrete due to seismic activity of up to 9 points – Alexander Balabin shares – I invested a lot of time in creating formwork casings. I made sure that these formwork casings had a certain size, and the fastenings were in certain places, so that it would correlate with the impost pattern, and with the horizontals. When you remove the casing, the concrete must remain as it is, without any adjustments needed. Whenever the builders did not succeed at the first attempt, I made them cut off the concrete and start all over again. For window openings in the form of pebbles, so-called shells were made in the carpentry industry. Then matching aluminum frames were made, which then fitted in the openings without any plaster. I think that the builders have coped with the implementation of the project by 90-95 percent.

As for the ellipse coverage, we struggled with it for a whole year. We seriously pioneered this technology of glass fiber concrete with a polymer coating in this region, and in Russia, for that matter. You can only find something distantly similar to it in Zaha Hadid’s Geidar Aliev Center in Baku. Because of the heat, it was difficult to achieve homogenization of the outer layer. The team of Andrey Poletaev, the authors of the Zaryadye Park, first intended to make a coating from lamellas and even manufactured them, but then abandoned this idea because of the unwanted seams. We decided to apply the coating using layer-by-layer spraying. But if you do not do this continuously (people also need to have lunch and sleep), the liquid solution remains in the hoses, which needs to be washed away with white spirit, and then because of this, the coating hardens poorly, with bubbles and all sorts of other issues. This problem was also solved. In other words, a lot of difficulties were overcome in the process of work, but, in the end, everything worked out.”

The interiors of the winery continue the themes set by the outside design solution. The brutal-looking production rooms with concrete walls and metal equipment, at the same time filled with light streaming from the windows, look (or you could even say “sound”) as powerful as a rock-n-roll band.

The concrete staircases connect the spaces of the floors, where, expectedly, works of modern art will be exhibited. Just as dramatic and austere are the outside staircases.

The interiors in the show and tasting area are quite different. These are expressive white supports matching the outside parametric shape of the “pebble”.

The design of the wooden demonstration “column” in the reception area was also done by Alexander Balabin.

“I already said in another interview how lucky we were with this Cote Rocheuse winery – Nobody ordered a monument of architecture from us. However, I wanted to design something as honest and as durable as good wine. Hence the exposed concrete both outside and inside. Concrete is a natural and durable material, just as wine is a natural product. Modern architecture with all these hang-on facades is meant to last 50 years max. The ventilated brick facades in actuality are 2cm thick; behind them, there are metallic mounting subsystems and heat retainer. Our winery with the main foundation made of three-ply concrete will stand for five hundred years or more.”

The architecture of wineries today is a genre as popular as the architecture of museums of modern art. Such a commission is something that many architects dream to land. The clients regard the architecture of wineries as part of the show in the sophisticated art of winemaking. Over the recent 20 years, all the international stars of architecture have been spotted in having a go at this genre. The first one was Herzog and de Meron, who, having piled up a winery of gabions in the Californian valley of Napa, at once received a Pritzker Prize in 2001. Just as spectacular were projects by Richard Rogers, Zaha Hadid, Kalatrava, Norman Foster, and others.

Finally, these trends came to Russia. Despite the prohibition proclaimed by Gorbachev in 1986 and the cutting-down of vineyards (Alexander Balabin mentioned this fact in an online presentation of his project for WAF), domestic winemaking is still developing, although this process is far from fast. For example, the vineyards of “Skalisty Bereg” began to grow in 2011. The owners, of course, want to add symbolic capital to the wine, which is surely provided by a memorable architecture. For the same purpose, wineries are combined with galleries of modern art. In recent years, a number of works in this typology have appeared. The “Skalisty Bereg” wine gallery has already aroused a lot of interest among the wine tour operators, and a special excitement is associated with architecture. As for the residents of the Krasnodar region, they already consider the “Skalisty Bereg” winery to be one of the biggest local attractions.