The overview. Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist at the Novodevichy Convent

Copyright: © Utkin Studio

The Incident with the President

So! Straight off: the order to restore the Church of John the Baptist came in 2012 from the President of the Russian Federation himself. This curious story was told by Metropolitan Yuvenaly: “... 15 minutes after the President’s car left the Novodevichy Convent, there was an alarmed call from the mayor’s office, and they were like: “We heard you have blown-up church there?” I calmly replied: “Yes, right at the walls of the monastery.” Then they go, even more alarmed: “And when was that?” And I go: “200 years ago.”

In 2014, the scientific supervisor of the project, Andrey Batalov, proposed to make one of the versions of the temple to Ilia Utkin. “We put the model of the temple in the office of Metropolitan Yuvenaly, he examined it for a long time, and finally accepted this version” – the architect shares.

The church was built according to the Moscow program “200 churches”; a significant role in financing and organizing its construction was played by the St. Petersburg philanthropist, patron of arts, and temple builder Igor Naivalt – Ilia Utkin explains. At Igor Naivalt’s expense, the volume of the temple was constructed, and the collection of funds for the decoration of the interiors in the monastery was announced through donations, “notes” – bricks bearing the patron’s names: names for prayers for health are indicated in colored inscriptions, and names for prayers for repose are indicated in white.

Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist at the Novodevichy Convent

Copyright: © Utkin Studio

Why the church was blown up 200 years ago

Napoleon ordered to blow up the parish church near the walls of the monastery not when his army was beating a retreat, as reported by the media of those days, but on the contrary, immediately after the French troops occupied the monastery – in order to clear the field around the fortifications and, if necessary, build up an effective defense. That is, although the French army was indeed “godless”, since it inherited the atheistic tradition of the French Revolution, the church was blown up not for ideological reasons, but for military necessity (for ideological reasons, the French garrison a month later, then already beating a hasty retreat, laid gunpowder with lit fuses under the monastery cathedral, but the courageous nuns managed to put them out).

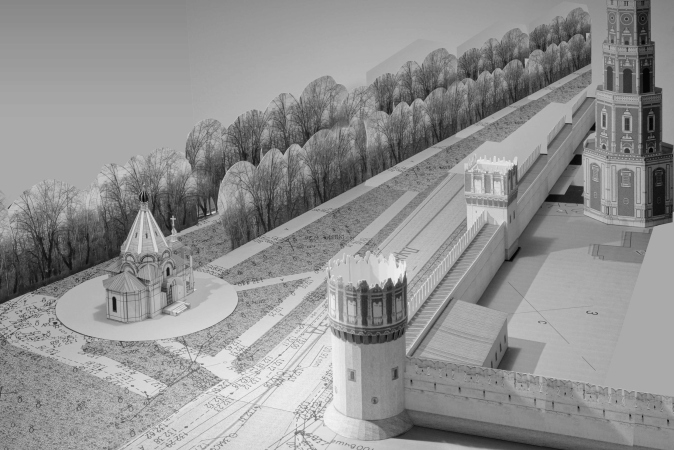

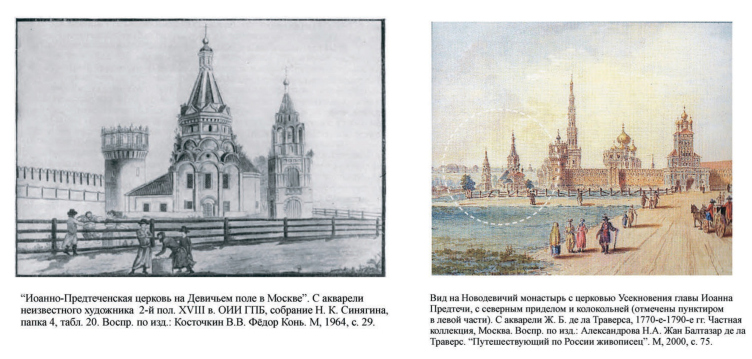

The temple of the XVI century

According to chronicles, the parish church next to the eastern corner tower was founded in 1525 – at the same time as the Novodevichy Convent. For some time it was wooden; then in the second half of the XVI century it was replaced by a stone building – a slender church with a hipped-roof. Its architecture is similar to the Church of the Great Martyr Nikita in the village of Elizarovo built in the 1560’s, and the Church of the Nativity of Christ in the village of Beseda, built at the end of the XVI century during the reign of Czar Boris Godunov. This is why, the historian of Russian “serf” architecture Vladimir Kostochkin dated the temple at the Novodevichy Monastery as belonging to the end of the XVI century, while the scientific curator of the restoration of the temple, Andrei Batalov, dated it to the 1560’s, or even more broadly, to the second half of the XVI century. Batalov’s article about the church and its restoration is available here (Russian).

The new conditions

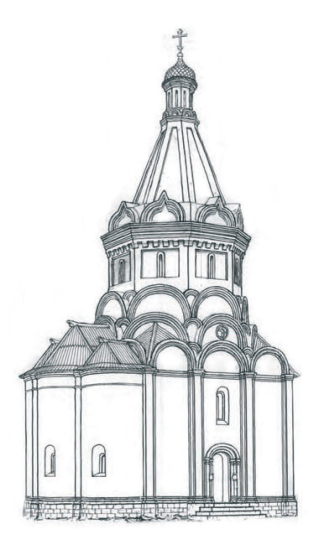

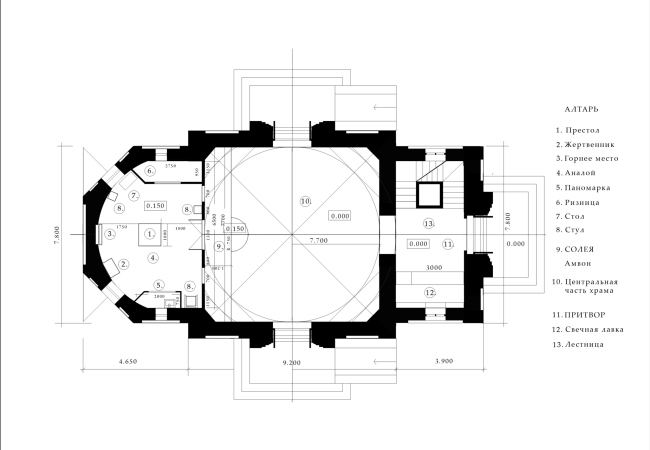

The temple designed by Ilia Utkin does not look like the church that was blown up by Napoleon. In order to dispel all the speculations about copying and its exactitude, the architect even calls his project a “monument to the temple” or a “museum” church.

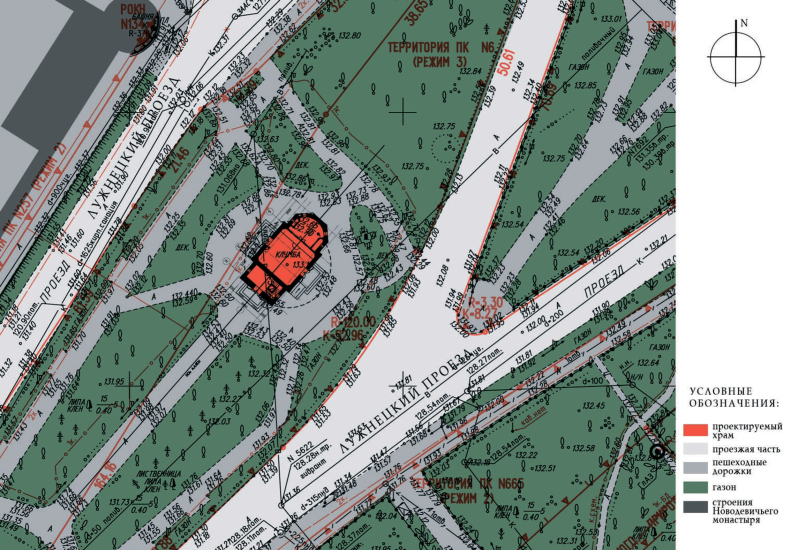

The XVI century church was about 35 meters high. In the protected UNESCO heritage site area, strict restrictions apply, and the height of the new building was determined as being lower: 20 meters with similar plan parameters. In total, this yielded quite a different set of parameters, rendering exact recreation of the historical temple impossible – not to mention the absence of the original draughts and plans. In addition, the new temple is located slightly further to the east than the lost one, whose foundation ditches, the stones of which were completely taken away still in the XIX century, are located closer to the monastery wall, at the site of today’s driveway. The place for new construction was found on the circular lawn between the two Luzhnetsky drives. This solution spared the trees from being cut down. Another thing that was changed was the orientation of the apses – the church is built parallel to the driveway and along the axis of the square, and its altar is facing northeast. This solution is correct from the town planning standpoint; in addition, as the author of the explanatory note, Andrei Batalov, rightly emphasizes, the temple altars of the Middle Ages did not always look strictly to the east – often amidst dense urban construction, churches were placed parallel to the streets. Furthermore, we will note here that the orientation of the altar to the northeast was often caused by the fact that churches were laid in late spring and early summer, looking at the point of sunrise, and at this time the sun rises in the northeast.

Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist at the Novodevichy Convent

Copyright: © Utkin Studio

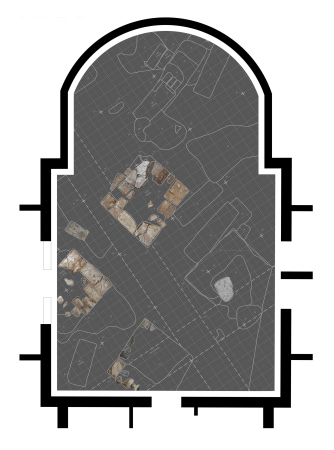

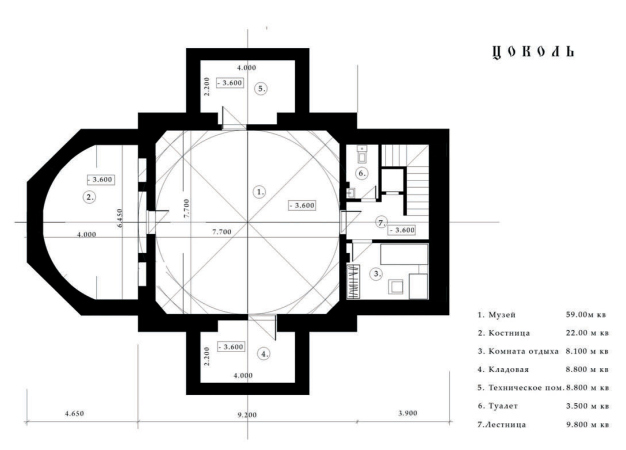

The Museum

One of the main prerequisites for the appearance of the new temple in the UNESCO protected area archaeological excavations and the organization of the museum. Its exposition is hosted in the basement tier of the church, at a depth corresponding to the layer of the above-mentioned archaeological finds. The white gravestones were installed in the places where they were originally found, while in the center of the hall the foundation of one of the four pillars of the XVII century bell tower is conserved. Everything is almost ready; the architects only have to add a few showcases to display small finds (mainly church utensils). After the showcases are finished, the exposition will open to visitors.

Ilia Utkin

The Museum of the Historic Temple in the basement is the key part of the project. It is dedicated to the excavations carried out at this place by archaeologists under the leadership of Leonid Andreevich Belyaev.

The ceramic floor of the museum is an archaeological tracing paper, very much like graph paper. The floor will be highlighted from below. According to the plan, the gravestones, mounted on metal foundations, will look as if they float in the air.

The ceramic floor of the museum is an archaeological tracing paper, very much like graph paper. The floor will be highlighted from below. According to the plan, the gravestones, mounted on metal foundations, will look as if they float in the air.

Thus, the old church will be commemorated by a museum, as well as by the dedication of the throne and the typology of the tent-roofed temple.

The hipped-roofed temples of the XVI century

The hipped-roofed temples appeared in Russian architecture in the XVI century, and disputes about their origin are still going on. The most plausible hypothesis to date says that the first stone hip-roofed temple and the prototype of all subsequent churches of this particular typology was the Church of the Ascension in Kolomenskoye, built in honor of the birth of the son of Vasily III, the future Ivan the Terrible, by the architect of the Italian origin Peter Maly. After that, hip-roofed temples were out of construction for a while – until the young prince grew up, proclaimed himself the Czar, and started the Kazan campaign. The campaign turned out to be very successful, and the construction of new hipped-roof temples was associated with its success, the most famous of these temples being the Cathedral of the Intercession on Red Square, aka the St. Basil Cathedral. Under his influence, a whole number of new hip-roofed churches of the second half of the XVI century appeared, one of which was the Church of St. John the Baptist near the Novodevichy Convent.

The result of generalization

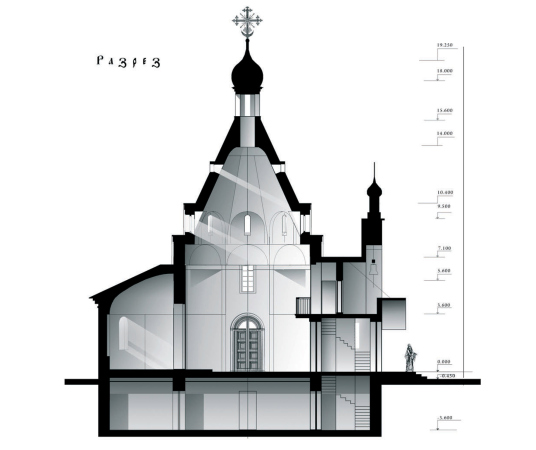

We will note here that the temple that the architects ultimately got is more reminiscent of churches built not later, but earlier than St. Basil’s Cathedral, and not necessarily hip-roofed, but simply associated with the work of Italian architects in Moscow. Full of plastique, the profiles of the arches, friezes and cantilevers in the interior, against the background of whitewashed brick walls, bring up associations (however remote, of course) with the round Church of St. George in Kolomenskoye, and maybe even the Cathedral of the Assumption Monastery in Staritsa.

Other elements, on the other hand, are hard to visualize in the XVI century: for example the facets of the octagonal bases were never crowned with just one arched gable at the bottom of the tent – rather, this is a technique of the XXI century. In the XVI century, there were no 5-faceted apses (multifaceted and straight rectangular did exist, but not 5-faceted ones). The positioning of a wall-shaped bell chamber above the entrance, and especially semicircular pillars next to its inner chamfers, rather remind Art Nouveau churches or the European 1930’s; if we are to look at the west façade from the park, the composition will look somewhat European, and even with some notes of Toscana romanticism.

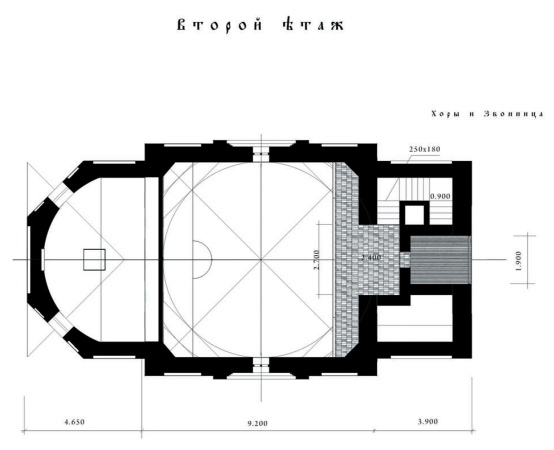

We will also note here that the bell chamber above the western vestibule replaced the XVII century hipped-roof bell tower, which stood to the northeast of the former church.

Interestingly enough – even though I doubt that anyone will pay attention to that – the corner trumpet vaults that we see where the transition from the four-facet to the eight-facet bases takes place – some kind of curious triangular cases that cover the church’s corners on the sides of the gables – are not hidden behind the decorative semicircles of kokoshniks: this technique is typical for temples of the first half and middle of the XVI century, and is definitely the result of historical research. On the other hand, on the inside the construction of the trumpet vaults is quite modern, these are flat triangles instead of arches, which is quite permissible with the concrete construction (monolith reinforced concrete with ceramic blocks and brick coating).

In a word, this is a modern temple, grown from the commission’s conditions, constraints, wishes, and supervision, yet still featuring a fair number of elements that, however conditionally, point to the XVI century. The reference points tie it to the epoch, which is not exactly popular with modern Russian church builders, but which is conditioned by the year of build of the previous temple.

On the other hand, Ilia Utkin is a classicist architect; his portfolio includes a rather large number of temples of classicist architecture – alas, most of them remained on paper. He is one of the modern masters who can stand up to the task of designing a temple suitable for the needs of the Moscow Patriarchate – not too vibrant, but noble and restrained. That, on the one hand, became the perfect match for the new church in a park protected by UNESCO, and on the other hand, successfully coincided with the range of techniques of XVI century architecture associated with the works of Italian masters and even Peter Maly. The reverse is also true: the Italian buildings of the XVI century in Russia turned out to be resonant with the fundamentals of Utkin’s architecture.

The light and the canopy

Now the temple is open very rarely, in the fall, it seemed, it was only possible to get inside it on Saturdays. Which is a pity because its interior design is its most interesting and atmospheric part.

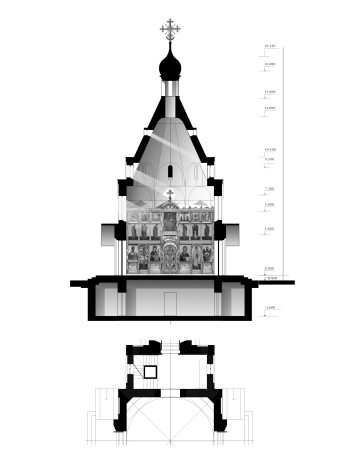

On the inside, the temple is clear in a Renaissance way even though you cannot say that it’s simple. The aisles leading to the eight-facet base and the tent are marked with rows of little arches resting on large cantilevers, full of plastique, which, surprisingly, do not make the interior look any heavier, but only emphasize the “hovering” effect, forming an image of a lightweight tent, stretched on weightless pinpoint supports “levitating” on the surfaces of white walls. The whirling of the arches is mesmerizing and allows you to acutely feel the effect of the centric space, shaded by the “dome” tent. The centric churches were the pinnacle of the art of the architects of the Italian Renaissance, and the Russian hipped-roof churches are their direct heirs and incarnations. The interior designed by Ilia Utkin not only signifies this, but makes you feel it really strongly. Some forced squatness of the exterior proportions of the temple, having to do with the ratio of the construction blueprint to the maximum permitted height, is completely redeemed by the imagery of the interior space, where the width of the volume turns out to be rather a plus, since it gives space: the dome turns out to be wide, and there is plenty of light even on a overcast day.

It should also be remembered that the effect of the tent hovering on pinpoint supports is not observed in all Russian hipped-roofed churches, but it is very well manifested in the Church of the Ascension in Kolomenskoe, where the octagon base rests on arches and capitals of pilasters, clearly distinguished against the white background of the walls.

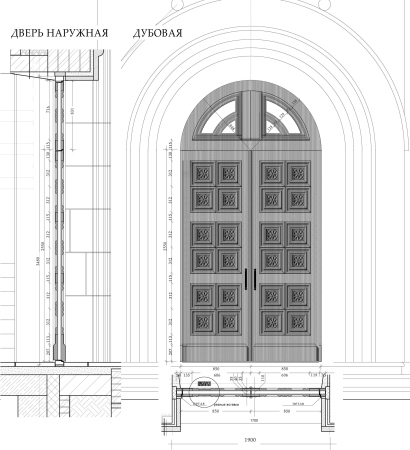

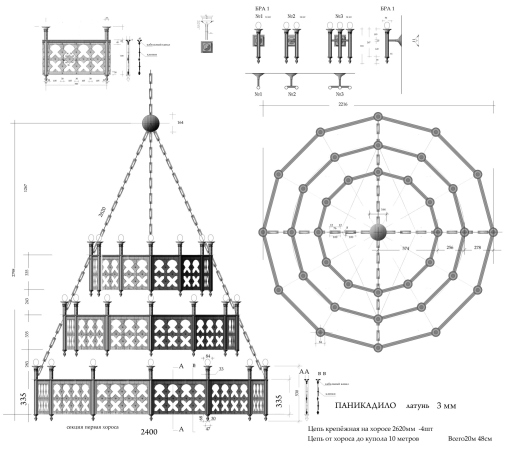

All the interior design was also done by the architect. The carved wooden iconostasis with the royal doors and side entrances has a conventionally ordered structure: the local and Deesis tiers are traditionally separated by a narrow festive row with square hallmarks. Ilia Utkin also designed the wooden doors framed with stone arched portals, the chandelier, the canopies, and the wrought-iron fence in the park. Their decorative patterns are united by the motif of the cross.

The overview with a tower of the Novodevichy Convent. Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist at the Novodevichy Convent

Copyright: © Utkin Studio

The golden chandelier is designed in the ancient form of “corona lucis” – a ring-shaped lamp, known since the Byzantine times and subsequently gradually replaced by branched candelabra; its stepping shape echoes the triangular space of the tent, emphasizing its “ascent”.

The icons and mosaics displaying the image of John the Baptist were created by graduates of the Department of Church Arts of the Orthodox St. Tikhon University for the Humanities.

When asked about his creative method of designing temples, Ilia Utkin was quite unambiguous: “You cannot do architecture that only you need. You must create a temple that will also be a temple in the eyes of the priests and in the eyes of the parish <…> It is traditional. It has to do, first of all, with the liturgical action. Inside and out, it must look like a temple, and not like some factory or concrete palace. And as long as you stay within your historical prototypes, it’s quite permissible to use proportions and materials of your own.”

This is how it ends up in the fact that the forms are seemingly well-known, but they are revisited by the architect anew. The past is not pushed back off stage by the author’s self-presentation, but opens up to the thin nuances and, stopping being the past, turns into the present. However, to really open it up, an author’s effort is required – a copying artist would not be up to the task. What we are seeing is an architecturally expressed humility, a focused and prayerful mood, a quivering, gentle, idyllic, artless attitude to the architecture of a hipped-roofed temple, against the background of which the barbarity and pretentiousness of modern temple construction seem to be nothing a passing phase.