The house is being built on the Vasilyevsky Island, on the block that faces the Lieutenant Schmidt Embankment, and within a dense historical environment, next to the houses of the XIX and the early XX centuries, in the stead of the now-demolished Aluminum Institute that stood here in the Soviet time. The main vis-à-vis of the new house, situated not exactly across from it, but still within the visual range, is the monument of classicism architecture, the Gorny Institute, designed and built by Andrey Voronikhin (1806 – 1811). “Andrey Voronikhin is really my hero, he was head and shoulders above Rossi and Kvarnegi” – Stepan Liphart says, explaining his love for the author of the Kazansky Temple with his ability to create a special “space of beauty” around his works.

A house with a courtyard

The name of “Little France” was authored by the client, Alexander Zavyalov, and is based on the pearly “Parisian” coloring. The light-gray fiber concrete, combined with exquisite wrought-iron grilles and French windows reaching to the ceiling, does indeed remind you of the French capital. It was also the client who proposed to build a courtyard – and this coincided with the architect’s intentions because a composition of a house with a courtyard creates a very Saint Petersburg image.

And, although courtyards or “courts of honor” are characteristic not so much of the Vasilyevsky Island as of the Petrograd Side, the 20th line of the Vasilyevsky Island does have a historical building with one, which means that the architect did address the rhythm, the scale, and the parceling of the historical construction. As for Stepan Lipgart himself, he names his main source of inspiration as being Lidval, whose courtyards are to be seen in the Lidval House on the Kamennostrovsky Avenue, and in the Tolstoy House on the Rubinshteina Street. This was also the source of inspiration for the grand propylaea.

The first thing that came to my mind, however, was the House of the three Benois with its grand courts of honor. Either way, I think, there is a reference to the neoclassicism of the Kamennostrovsky Avenue. This street, which was built within a span of ten years from 1905 to 1915 – the time of the “vertical cultural curve” of our country – is the Mecca and the endless source of ideas for the masters of traditional architecture, where architectural masterpieces and techniques are concentrated, still relevant today. Basically, in your mind’s eye you can easily see the new house in that environment, style-wise, scale-wise, and in terms of the sheer number of inventions.

A tenement house of the Silver Age as the perfect housing

The neoclassical houses of the Silver Age and the Soviet Art Deco are commonly considered to be the perfect example of modern housing. It is not by chance that the Tolstoy house or the Levinson house on the Karpovka or Moscow’s high-rises are aggressively marketed as the hot places of residence for the young and affluent hipsters of today.

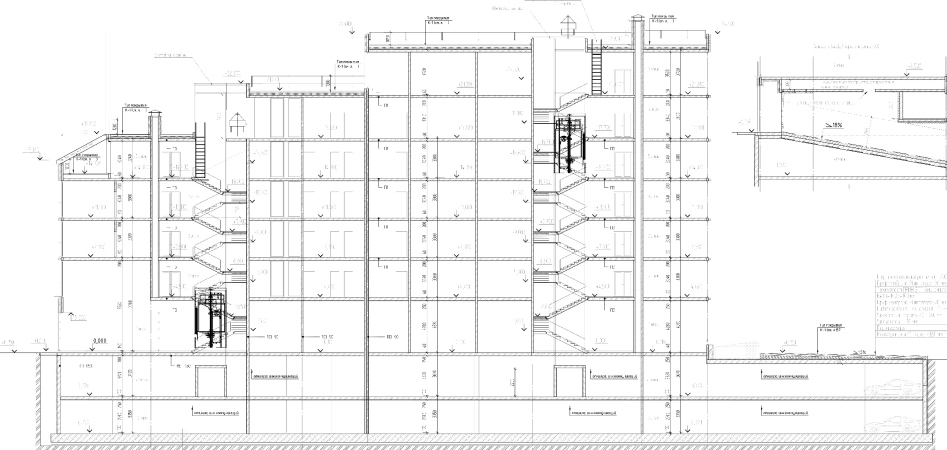

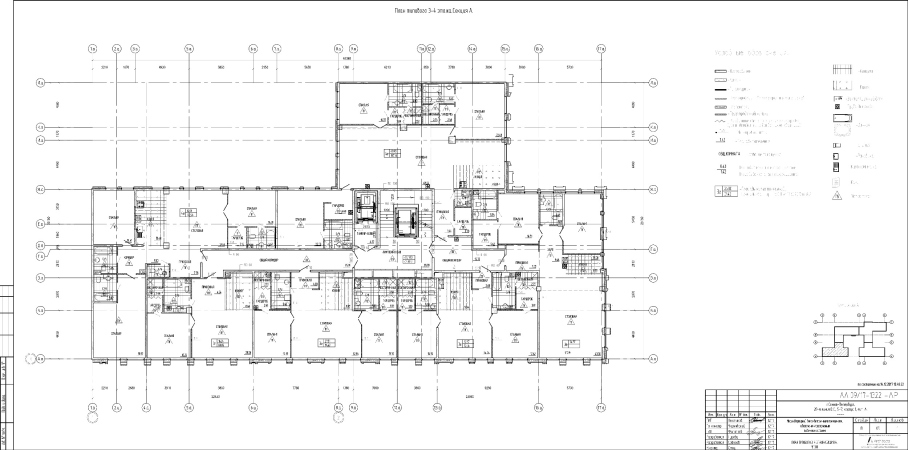

Today, there are no problems with the amount of light in the courtyards. “Little France” features two courtyards – a grand one and an in-block one – plus a few small-sized yard territories, neatly organized. While in “Renaissance”, the previous Liphart project, the context was essentially presented by a high-rise sleeping-belt neighborhood, and you simply could not cancel the 20-story-high scale, this project on Vasilyevsky Island, thank God (and thank the height restrictions), has exactly as many stories as needed in a historical city. The “French” house steps on the redline in symmetric four-story units with a fifth attic floor, and then, withdrawing into the depth of the yard, gradually increases its height up to the main unit, seven-stories high. This is already a fundamental difference from the houses of the Silver Age, in which different parts, if any, of course, had the same height. And, if you have ledges – you will have terraces. Generally speaking, terraces, tiers, and registers, as well as the ledgy composition of units, are very relevant in a modern city.

From Leo von Klentze to Burov

The architecture of the house on the Vasilyevsky Island can be best characterized as geometric and ornamental – the two qualities that nevertheless do not conflict with the architecture of orders. In this case the architect is basing himself on the experience of his predecessors. Stepan Liphart: ““Little France” shows references to the neo-Greek German style of the New Hermitage designed by Leo von Klentze. The architecture of this building made a great impression on me, especially its decor, based on strict geometry and repetitiveness. In my project, it is closer to Art Deco, more generalized and more geometric; at the same time, I borrowed from Klentze a number of plastique elements of the facade.” Indeed, some of the details of the Liphart house, such as acroterions in the window frames and pilaster porticos are the joints of the cornices did come from the New Hermitage: they are different, yet in the same places. The flat and ornamental character of the side-end facades of the New Hermitage was quite unexpected by the standards of those days, passing quite unnoticed behind the portico and the atlases, and, mind, this is almost XX century.

From the flat and ornamental order authored by Klentze, one can draw a line to the Andrey Burov house on Tverskaya with ornaments executed in the scratch-work technique. Accordingly, Stepan Liphart entwines this line into his own work, and it starts working as the intermediate context, actualizing different layers of the neoclassical tradition.

“Little France” housing complex. View from the yard to the street from the north

Copyright: © Liphart Architects

What is interesting is that the order elements of the French house, although flattened by the ornament (ornamented pilasters are always more incorporeal because they are “clad”) still do not disappear completely. When Sergey Tchoban used ornaments in the Granatny Alley, he created a complex light-and-shade facade surface – and this is his manifesto expressed in his book “30:70. Architecture as a balance of forces” – he most likely based himself on the rationalistic modernist architecture. Light and shade – yes, architecture of orders – no. Stepan also takes into consideration Sergey Tchoban’s experience (currently, test work with fiber concrete is being done, of which the client has his own production facility; they are making tests to make the surface texture as beautiful and as deep as possible). In Liphart’s project, however, the articulation of the facades is more prominent and traditional: not just grid lines but order decoration, a structure of piers and risalits. The theme of porticos (external window frames two stories high with pilasters and a fronton) on the risalits alternates with a less saturated part of the facade (intermedia), where the pulse and the rhythm of windows are still present but elements of architecture of orders are almost absent.

The facade of the tall central unit is marked by a grand risalit with an Art Deco portal (almost like on the building of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Moscow), a portico of the dress-circle, and a crown inspired by the clock turret of the Marble Palace. As usual, this facade in the depth of the courtyard becomes a theater backdrop, getting a distance that increases the perception effect. The already mentioned “Lidval” propylaea at the entrance add to the solemnity of the courtyard’s visual appearance. After all, a courtyard is always a very strong spatial experience.

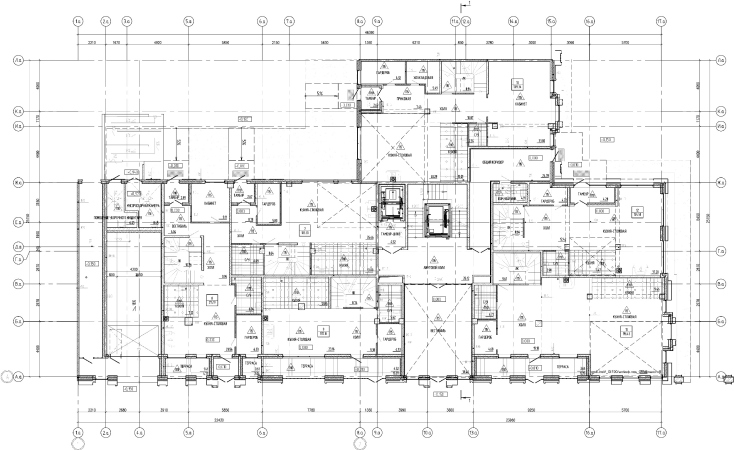

In addition, Liphart attempted to make the facades reflect the inner structure of the building, such as division into individual apartments, and mark the entrances to apartments and lounges with portals and frames. There is a rule – let us conditionally call it the rule of Mikhail Filippov, because he pronounced it in the 1990’s – that the windows of different stories of a residential building must be different in size and decoration because there is a family that lives here occupying the whole floor. Such structure is characteristic of the houses of the 1910’s, yet it disappears in the architecture of “the country of the victorious proletariat” in the 1930-50’s, when all the windows become completely alike. Filippov called for getting back to the Silver Age. Today, of course, such families that can afford enfilades of eight rooms are few and far between, and generally our society is more atomized, and, hence, the apartments are smaller. In the house on the Vasilyevsky, however, all of the apartments feature French windows (I do not even know what social conclusions I am to draw from this – I will leave that up to you to decide); they are of the same height but of varying width. Some of them are grouped in threes marking the borders of the apartments. In this case, the inner structure is shown by different means – these are tiers and risalits, pilaster side of the cornice, composition in the spirit of architecture of orders, lower galleries of the city houses, and the upper terraces of the penthouses.

Anyway, we see the traditional “tripartite” character of the building, a symmetric composition from the street side, and orderly techniques of articulating the facades. At the same time, it is clear that the building was created in the XXI century. So, what is new about it?

The dialectics of architecture of orders and stained glass

Here I am approaching my favorite subject of the order / glass ratio that is promising to become the main one on the XXI century. There is a thousand ways of combining the two, for example, in such a genius way as Samoilov did in the “Nauka” health resort in Sochi (1938), where the stained glass windows, pierced by the sunbeams, miraculously supported rather sensuous order elements, columns and porticos, hovering in space. According to Stepan Liphart, his goal was to “achieve the optimum balance between the order elements and large glass surfaces. The glass surfaces yield a lot of light. But this emptiness is compromising the tectonics of the building.” The windows of the house on the Vasilyevsky Island are almost transom-less, and the facades are indeed perceived as an order framework that is suspended in space. Yet this framework is sturdy and well thought out. In spite of its flat character, it has a lot of layers in it, and the very order of the graceful dry drawing is very convincing and tectonic. This is not the romantic vitality of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, but the transparent slenderness and knight-like perseverance of the classical amidst the overall chaos. Some kind of “in defiance” by Hermann Hesse, one of whose books became the inspiration for the headline of this article.

“Levinson softened by Lidval”?

Trying to come up with some sort of a formula for the style of the house on the Vasilyevsky Island, Stepan Liphart said that this was “Levinson softened by Lidval”. As for me, I do not really sense Levinson here, unlike in the “Renaissance” housing complex, where his influence is obvious. The large scale and the vast expanses of land required powerful plastique of the facades that was expressed in the mega-order constructed of bay windows protruding far ahead. As for the signature Klentze flat surface, it is indeed felt in the French house. So, probably, a more apt formula would be: Klentze-Lidval-Levinson-Liphart. This is what I mean by the make-believe communication with the masters of traditional architecture – something similar to what takes place in the Hermann Hesse “Journey to the East”, where in one place meet Mozart and Anselm of Canterbury, Paul Klee and Hesse himself, the poets and artists of different centuries.

The beaming ornament

Generally speaking, Art Deco sounds pretty muffled here. Most of it is concentrated in the portal of the main entrance and in the outstanding laconic cornices of the in-yard units, as well as in the beamy ornaments that adorn the pilasters and the propylaea, not so much in the spirit of Voronikhin as reminiscent of the Soviet coat of arms. Stepan Liphart states that these motifs of a diagonal and an arc, added by triangles in the friezes, first came to him, and he only later realized that a triangle was a pair of compasses. In any case, the motif is beaming and radiant, born at the Airport metro station. Also, Art Deco is felt in the deluxe formats of the apartments. The terraces, for example, bring up associations with the tribeca penthouses in the Art Deco houses of New York. The terraces command breathtaking views of the most beautiful city in the world.

Personal gallery and personal entrance

Alongside the penthouses, Little France uses the deluxe format of the so-called city houses – two-story apartments with an individual entrance from the street. Historically, city houses are few in Russia, but recently, they have become more numerous. This is like a townhouse, only set into a mid-rise residential building, with a public zone on the first floor and bedrooms on the second. The whole idea presupposes friendly society, which, of course, was unimaginable in Russia of the 1990’s. This affirms the dignity of privacy. In Great Britain, there are plenty of street entrances, for example – it is enough to remember these colorful narrow doors, often featuring a coat of arms, framed by porticos. In “Little France”, the entrance to the city houses is made through gateways with ornamental wrought iron fences – an homage to the Summer Garden that features “the most beautiful fence in the world” – in the summer time one can leave a go-cart or a bicycle. The gateways exit into the 20th line of the Vasilyevsky Island, quiet and green, with almost no vehicles or pedestrians on it. Essentially, these gateways are indoor galleries in the body of the building. The city houses, situated on the yard side, feature little gardens where one could plant strawberry or just have a cup of coffee.