Whom do you look upon as your teacher?

I decided to take up architecture only in the 10th class at school – at the suggestion of my mother, who, though she was a doctor, always felt a strong attraction for art. After a year of attending art classes, I entered Odessa Institute of Engineering and Construction, from where, three years later, I switched to the Moscow Architectural Institute (MAR CHI ). At the time I had only a superficial knowledge of the profession, and when I started rooting around in the institute’s library, I came across Konstantin Mel’nikov – an amazing discovery for me. His designs are very energetic, and they made a very fresh impression. I think he ‘charged me up’ when I was young. At that time there was still no published monograph on Mel’nikov and the architect himself was still alive. I walked around his house and even thought about calling in on him, but was too shy to do so. Mel’nikov’s house made a huge impression on me. Such a mysterious tower.

Personally, I have long since found an answer to the question of why Mel’nikov is such a R ussian architect. There are two principles that meet in him. The first is a breathtaking, irrational movement of the soul, an impulse to make everything spin around or spill over to one side, to present an idea that will have everyone gasping in amazement. This is a very Russian freedom of character and recklessness. The second quality is wit and invention. So non-rational movement of the soul is followed up by some very rational design work.

How do you hit upon the forms in your architecture?

Intuitively, I think. It’s important that a design should avoid being primitive or dull. There was a period when we said that a design is lots of beautiful lines. Then we said that it is a beautiful line. Then we began saying that a beautiful line is sufficient for several designs.

So you start with a drawing?

It so happens that my head works only in conjunction with my hand. Sometimes solutions come to you when you’re half asleep, before waking up. You pick up a pencil; and your vision disintegrates. And then suddenly you end up with something altogether different. Only hand and head working together – a kind of dual instrument. There was a moment when I realized I was never going to learn how to use the computer and gave up trying. I calmed down when I found out that Khazanov had also given up. And I realized that without a computer I’m actually quicker. My objective at the moment is to generate ideas. To get my young architects thinking. There was a very long period of almost ten years when everyone worked for small firms. We had small children we needed to bring up. So we did a lot of piecework to earn extra money, and for a long time I was very worried that I would get swallowed up in this and never produce anything creative. But, evidently, this was a period of accumulation. Then, when I learned that Lloyd Wright produced his most famous works from the age to 60 to 90, I calmed down and decided that I had it all in front of me. And it’s when you calm down that you begin to come up with interesting things. Although I’m always in doubt, always in despair (evidently this is the mark of a creative profession). I would say, though, that the most difficult part of our profession is attaining inner freedom. It’s only if you have this that your designs will seem graceful and the sweat and blood you’ve put into them not show. Freedom can give you a great deal. It makes it possible for you to stand on a new step each time and this, I think, is the most precious thing. You could say that we spend all our life moving towards a state of inner freedom, and only when we reach it can we start doing proper architectural design. Perhaps, if our projects have actually achieved something, then they are the result of those moments when we suddenly became free inside.

What is it that shackles you? Clients, context, the need for planning permission?

Usually, we shackle ourselves. It’s very convenient to blame something – clients or technology… But I’ve realized that we only have ourselves to blame. Even if your project has been axed, that means you didn’t defend it properly. Although it can happen that the client imposes his own solution, and you have to accept it, digest it, and remain on top of the situation. Incidentally, I collect all the material, all the information that has a bearing on a project – even the client’s scribblings and everything that was done by other people before we came along – since it all gets digested.

So external factors can be beneficial for you?

After graduating from MAR CHI , I got a job at the experimental sector of Moszhilniiproekt [the Moscow Housing-design Institute] under Yevgeny Borisovich Pkhor. There the experience of working on a number of reconstruction projects and the time we spent stewing in the old city taught us all about complexity, diversity, and ambiguity – in contrast to the then prevailing orthodox Modernism, which at the time seemed impossibly dry and emasculated. So reconstruction was where I learnt my stuff. For me seeing what used to be and then taking it to pieces and creating something new is an ideal direction in which to work. It’s very important to have an initial impulse – from the client, the site itself, or even an idea supplied by an employee, which I then digest in my own way. It’s not essential for my idea to be primary. I’m quite relaxed about that. Your reconstruction projects and buildings in the old city centre do not hide in their surrounding context; they’re very conspicuous.

Is this a principle of yours?

It’s is an utterly conscious principle. We told ourselves from the outset that the old should be old and the new should be new. But the new should be worthy of the old. It should exist without having to play to other buildings’ tunes. Previously, due to the smaller scale of projects, old and new rubbed shoulders within a single building; the new was heaped on top of the old, crawled all over it, leant against it. But now that projects have become larger, we can take the liberty of, say, creating a stylized superstructure on top of an old building, as they did prior to and after the war. And then, next to it or in the depths of the complex, we can build something altogether different. The contrast has moved: it’s no longer within a single building, but between two buildings.

At the beginning of the 1980s you took part in the competition to design the arch at La Défence. What did this give you? It was a chance to take risks and let our hair down – our first opportunity to take part in an international competition. There’s a small detective story connected with this event: in order to get our hands on the competition programme, we met an attaché from the French Consulate beside the monument to Tchaikovsky. Half an hour later, some people dressed as firemen came to our studio, supposedly to do a fire-safety check, and looked through all our papers. To take part, we needed a serious prize-winning architect. Our team leader was Professor Gol’zamdt, and the team itself consisted of a dozen or so young architects, including Khazanov, Skuratov, and Mikhail Kokoshkin; we all worked on the same project. As a result, it contained a host of different themes. The project didn’t win, but was shortlisted. Surprisingly, when we recently dug it out of the archive, we found it’s still of interest and not at all anything to be ashamed of. Then, by inertia, we took part in the Bastille opera house competition. For this Skuratov came up with an interesting idea. He played around with the typical theatre layout and invented a new variation. But his idea was then ruined by ‘pestilent’ architecture.

At the time were you aware of yourselves as part of the global context?

No, at the time we weren’t yet aware.

What currently strikes you as interesting in the global context?

The real interest is in what’s happening here in Russia. It’s simply a gift of fate. Everyone who’s remained in the profession has been rewarded by the way things have becoming so interesting here now. To begin with, we had second-rate foreign architects coming here; now it’s the first team that comes. And then people used to do sketches only for the sake of reputation, but now everything is for real; we have Foster working here. This is probably the most interesting stuff happening in the world right now.

So, you see the presence of big-name architects as a positive thing rather than as competition?

I’ve even found myself up against competition and lost out as a result. I’ve felt its effects personally. So I look upon it as a natural phenomenon, an element of nature. We were expecting spring, but then snow came instead. Well, it’s in the natural order of things.

What do you think of curvilinear architecture?

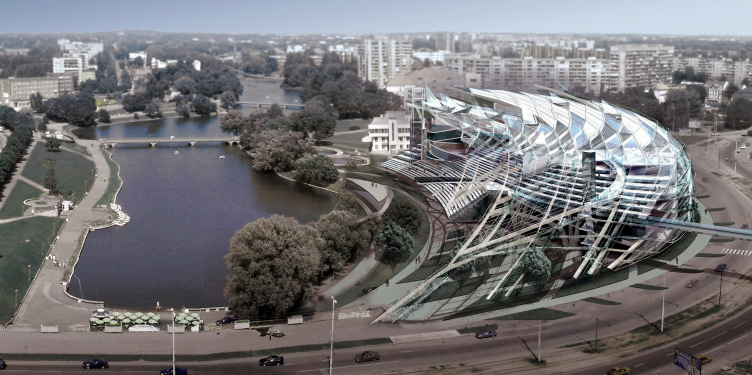

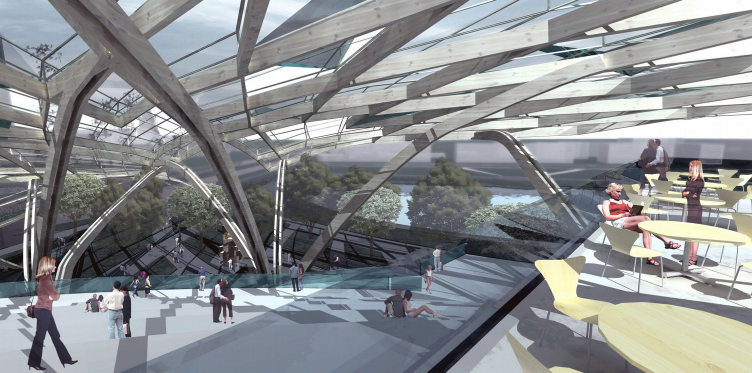

The real danger is when you allow a technique to become a law unto itself. Curvilinear forms were a reaction against dull rectilinear shapes. Then people very quickly tired of them and I too kept my distance, especially when there became so many of them, including in Moscow. Now I tend to work with diagonal grids and natural elements. Although this leads every time to collisions with technology, as, for instance, in my design for the theatre in Kaliningrad, where there are complex technological solutions which, if we are dismissed from implementation of this project (something which is already happening), cannot be realized to a satisfactory standard.Without the original authors the result may well be shameful for all concerned…

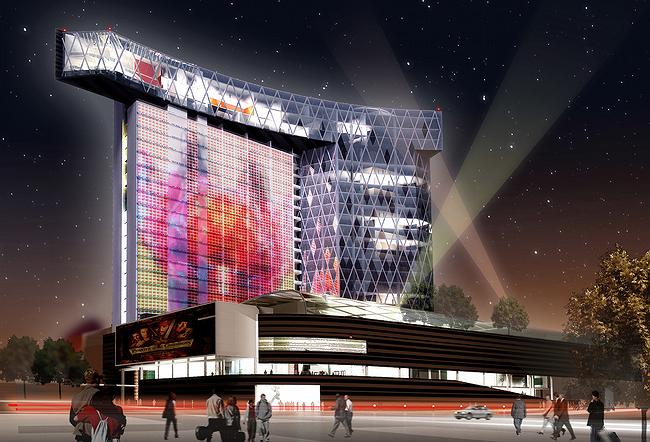

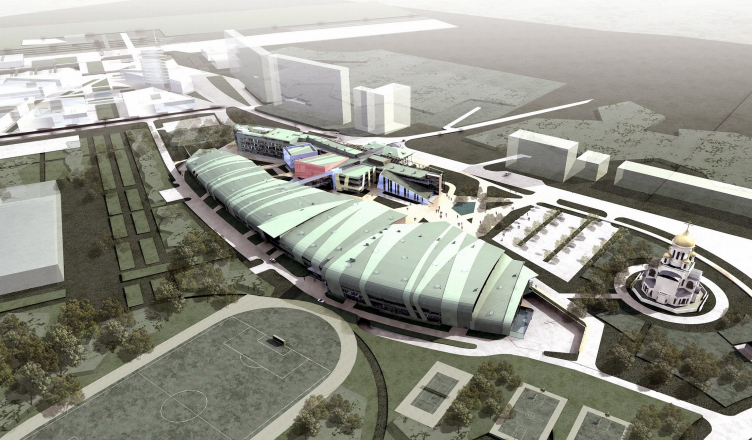

In addition to the theatre, you’re also designing a building with a media screen and a building over a railway. Do you specifically aim for modern technological solutions?

Undoubtedly. Of course, not every project we do manages to be innovative, but we do try. Sometimes this helps in promoting a project or in our dealings with a client. Today flash innovation is increasingly popular.

You’re not afraid to build on top of a railway?

Not at all. Perhaps because we’ve already seen such buildings. We made a special trip to Belgium to take a look at large complexes of this kind. There are consultants we can call upon.

You say that plastic technique should not be allowed to become a determinant factor in itself. What then should?

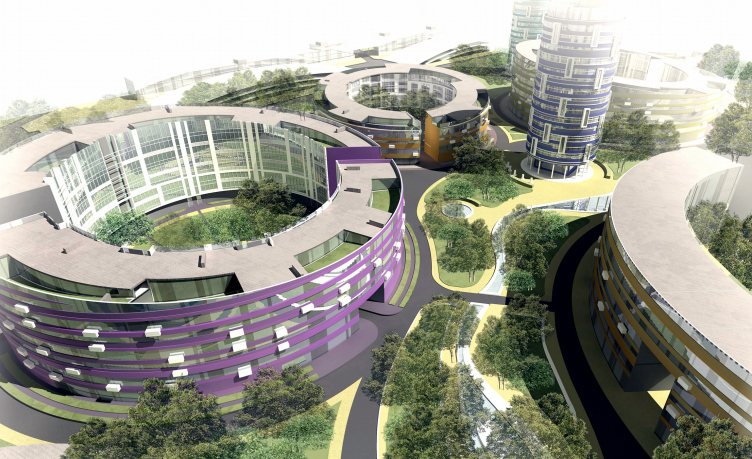

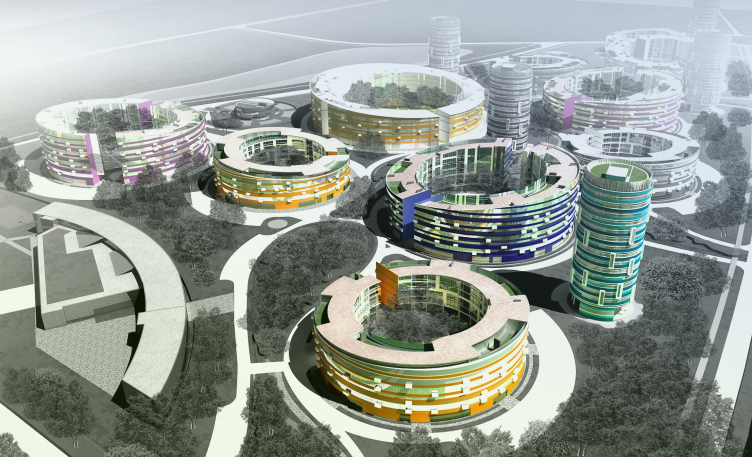

Different things in different projects. Currently, we are expanding our palette. For each project, especially commercial projects, we try to think up a logo, name, and image that will help the architecture. At this year’s MIPIM we showed a project which we’ve called ‘the pearl’. It’s a settlement screened off by a kilometre-long undulant building around its perimeter. Inside are single-family houses, a public centre, and a lake. There’s a restaurant on the water under a semi-translucent pergola-like dome made from mother-of-pearl triangles. It’s a genuine pearl in a genuine shell. And that’s the name we’re promoting it by – ‘the pearl on Il’inka’. We were fired up by the fact that this was to have been a competition between ourselves and Zaha Hadid. We were so scared and tried so hard, but then Hadid for some reason failed to take part. But we were stimulated. If it actually happens, it’ll be quite an event.

Your architecture is sculptural. This can be seen in your work from the very beginning. Is a sculptural quality your theme?

I suppose so. Previously, less consciously, but now more consciously so. A number of our designs have a hard and even form, but even so the form is slightly sculptural. On the other hand, your architecture is frame-based.

This was probably what has caused it to be described as ‘Deconstructivist’…

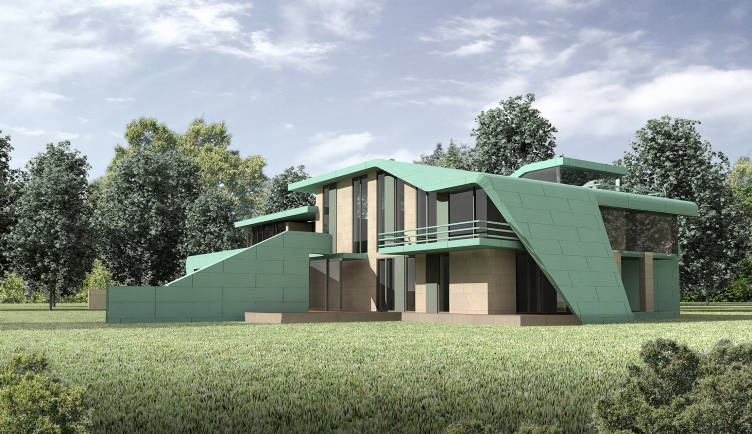

Frame-based structures have two aspects. The first is a frame that is easily read. Now that I’ve grown up and gained experience, I realize that this is very much a southern technique. It’s only in the south that you can set up a frame and then fill it in. And in my early projects such elements were imitative. The external column was in fact borne by an inner one, but you have the impression that the construction is bursting outwards. It’s a striking technique, and you can find it being used in Moscow today – detached and floating cornices and pergolas: these are southern techniques. It’s much more difficult to create your own, northern technique. The kind of ‘well-wrapped-up’ architecture whose insides do not burst outwards. It’s architecture that relates to cocoons and potatoes. This is closer to us because our direct prototypes are northern peasant houses where accommodation and production are gathered together under one roof. This kind of structure is all tranquillity and closer to natural lines: it’s all one piece and under cover. To create architecture without eyecatching projecting columns or structures, without baring the framework, is much harder. But it’s what is typical for us and could be taken as the distinguishing feature of our architecture. I suppose I still haven’t designed a single building that meets these standards, but I understand that if we are to keep moving forwards, then this is the direction we must take. The second kind of framework is internal self-discipline. Plans, regularity. When you have a regular grid, a structured floor plan. The lack of such a framework seems to me a mark of carelessness. All good architectural things are structured, internally modulated, proportional.

My final question is about your dream as an architect: what would you like to design?

In 2000, when we started designing an island on land reclaimed from the sea (before this had been done in the Emirates), my dream was to build such an island. In 1998 we had an idea for a sail building on Kalininsky prospect [in Moscow]. Then the sail building appeared in Dubai, and this dream vanished. When we designed the Yugra Island near Tuapse, we dreamed of creating an area reclaimed from the sea. I even had t he idea that I was a bit like God, creating a piece of reality, but then, when the project has failed to get built and I’ve got busy with other projects, the dream has disappeared. So my dream is always changeable and elusive. My dream, I suppose, is to attain inner freedom. And what I actually build while attaining it is not really that important.