We already wrote about the project of “Wine House” residential complex built by GALS Development in 2014 when the construction had already started. This housing complex on the Sadovnicheskaya Street is one of the rather early examples of cooperation between TPO Reserve and SPEECH, when the two architectural firms simply divided the sections of a residential building between each other – chiefly, for the sake of diversity of the façade designs: one of them, modernist, belongs to Vladimir Plotkin, the other is graced by latent ornamental classic, so characteristic of Sergey Tchoban’s creative experiments. In this specific instance, TPO Reserve also acted as the chief designer of the project.

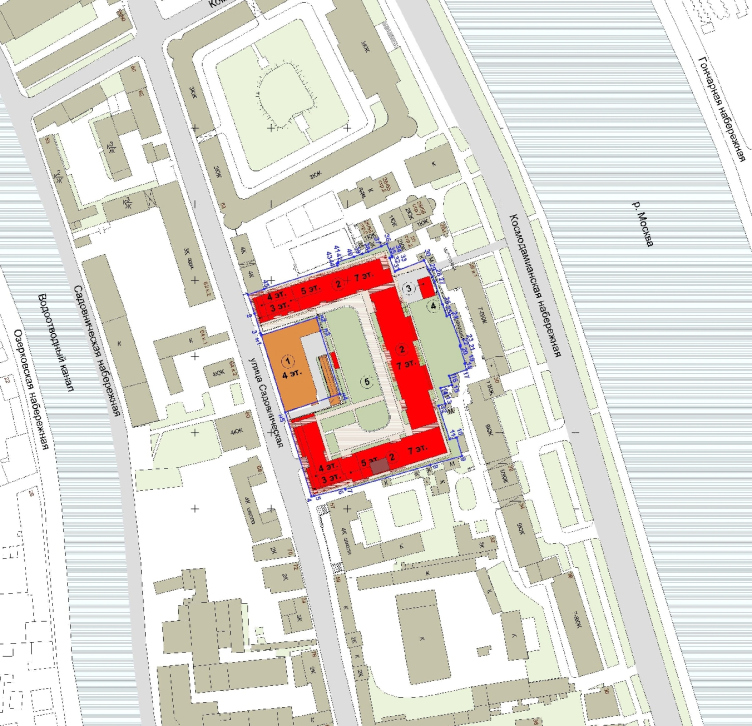

If we are to speak about the location, it is such a quiet place that you cannot even believe that you are in fact in the very center of Moscow. But then again, the Sadovniki District, situated on the Balchug Island, is quiet from bank to bank, which turns it into a perfect place for expensive housing. The price for the apartments ranges here from 7 to 10 thousand dollars per square meter, these apartments are mostly 100 square meters plus, sometimes even double that size, and half of the sections have been already sold. The place as such is a very interesting one indeed: it is surrounded by the buildings of the defense ministry from all sides. To the north, on the left down the Sadovnicheskaya, there is the former “Kriegscommisariat” built back in 1780 upon the project by Nikolai Legran, the author of Catherine the Great's plan for reconstruction of Moscow. Currently, it is occupied by the headquarters of the Moscow military command region, its yard containing a bunker from which the control of the military region is carried out; in 1953, Beria was executed there. Across from it, there stands the Office of Investigations of the military region. On the opposite side, on the right down the Sadovnicheskaya Street, there is a low-rise “Old Kriegscommisariat” built back in the 1740’s; today its yard serves as the park of the military unit.

And, finally, the Kosmodamianskaya Embankment is fenced off from Wine House by a string of Stalin-time residential houses which were built – surprisingly – during the Second World War, from 1940 to 1945. These are protected from the automobile road running along the waterfront by a string of trees, and, in turn, these securely protect the residential complex – the nearest house has eight stories in it, and the sections of the new complex standing next to it have seven. Between the yards – meaning, behind the rear façade of Wine House – appeared a small yard with a driveway, closed by an auto barrier, the rectangle 24х73 meters adjacent to the housing complex being organized and landscaped.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Location plan. TPO Reserve, SPEECH

The complex itself has occupied the territory of the former winery of Peter Smirnov, from whom it inherited the name of “Wine House” and the red-brick building of 1888-1889 stretching along the Sadovnicheskaya Street. In the mid 1940’s it was the place where “Cornet” champagne was produced. In the surviving building, the architects were able to find room for 41 apartments; its façades were cleared completely from the old paint, and, as part of the new housing complex it got a name of “Luxury Loft”.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

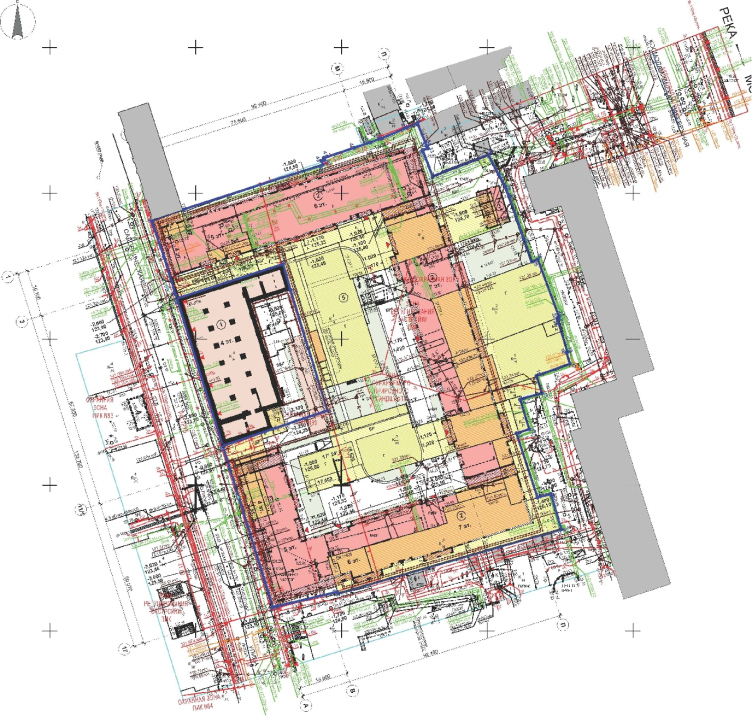

The new sections of Wine House are built, just as their Legran neighbor, in a regular rectangle, surrounding a closed-type yard. If the building of the XIX century had stood in the middle and had not been moved to the left, this would yield a perfect square, but this way, we see a composition that is slightly asymmetrical.

"Wine House" residential complex. Master plan. TPO Reserve, SPEECH

But then again, the principle of the classical “palace-type” symmetry is still implemented here, if only with a hint: the central section meets anyone who enters the yard with a ledge of a broad projection flanked by two other ledges on the sides. This layout is of a completely “palace” type; the central projection taking on the role of a “portico”, although you might say that it is drawn in a somewhat reverse fashion: instead of the main “podium” or “base”, what we see is a space beneath a cantilevered structure; instead of columns, there are piers between the windows, which, as the floors go up, grow ever thinner in the spirit of optical art, or, like the branches of a tree, dissolving into the sky.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

But the theme of a symmetrical “square” palace is, of course, not the dominant one here. What is more important is the two signature styles of Russia’s two best-known architects joined in one complex, a technique that was extremely popular in the 2010’s, when everyone was in search of different “hands” to bring extra variety to the integral housing front of the historical city. Such conglomerates of façades are oftentimes on the mottled side but here this is not the case. Everything looks smart and respectable, and one cannot rule out the possibility that the latent “palace” theme also dictated some common solutions or – which is more probable – each of the two authors possess such a bright artistic vision that the very fact of proximity to each other and the inevitable future comparison set the gentlemanly reservedness of tone. But then again, it is a well-known fact that Sergey Tchoban and Vladimir Plotkin often work on architectural ensembles together – for example, in “VTB Arena Park” or in the “Zapadny Port” housing complex. In this specific instance, however, what they divided between themselves was not whole buildings or even their units but façades and sections.

The integrity is ensured by the common silhouette and the authors’ approach to the height of the building: it lowers towards the Sadovnicheskaya Street down to four stories forming broad stairs of the terraces that command magnificent views. Just as important uniting role is played by the material – white limestone, which is now regarded in this city as a material that is at once respectable looking and historically correct, even though we know for a fact that there were almost no stone buildings in the old Moscow.

The façades designed by SPEECH sport the kind of limestone that is slightly more “classically” yellow, TPO Reserve showing a more modern sugar-white type. But then again, on paper the project showed a greater diversity of color; in reality, the former color is only slightly on the beige side, one has to look closely to see the difference. At some places, the stone is interpenetrative, which also provides a unison effect. In addition, the second material – black-colored metal of the broad lintels and thin grilles – is also used by both architects. You get a feeling that the architects paid close attention to make sure that their dialogue does not turn to a vocal argument. And the argument (if there is one, anyway) is now ostentatiously graphic, even of the “paper” kind, without any raised voices.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

The façades designed by Sergey Tchoban are closer to the classical patterns and proportions. Here, instead of cantilevered structures, the bottom tier chiefly rests on stone pylons. The thin verticals of the windows, grouped in threes, and the rounded corners of the projections put one in the mind of the rational modernism and Art Deco. At the same time, you will not find pure quotations of either of the two: everything is seen through a sort of a “metaphysical” prism, and all the elements of the composition are schematic, although still recognizable. For example, on the sunlit south façade of the north building we discover semicircular cutaways – “shadows” of the columns in the reverse relief. The dense and thin vertical grooves on the pylons look like flutes, although they are devoid of rounded shaping, plus, a multitude of cutaways, also predominantly of a fancy rectangular kind – all of this, considering the degree of generalization, refers us to the Italian 1930’s.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

What arrests one’s attention most of all is the ornamental carved pattern – a leitmotif of Sergey Tchoban’s architecture and his reply to his own concept that he presents in his book “30:70”, in which he writes about the necessity of making the surfaces of the buildings more sophisticated, working with texture and decoration materials. In this specific instance, this pattern is the heir apparent of the house in the Granatny Alley, and, just like there, it is supported by the ornamental silk printing on glass. However, in the Granatny Alley, there is indeed a lot of ornaments, they are chiefly based on the Byzantine prototypes, and are there in many materials. In the Granatny Alley, the carving on stone is diverse: from stylized yet still quite volumetric to quite flat, situated right in the middle between two surfaces, like a rubber stamp or linoleum engraving – something that does not have any claims to be of any “relief” kind. This last kind, the easiest one terms of texture, became the predominant one on the façades of Wine House. Due to the high degree of generalization, the prototypes are even barely readable here, and the желобок spins endlessly, sometimes in a dense and sometimes in a thin fashion, only occasionally allowing one to recognize outlines of a flower or a hop cone. Its purpose – namely that of “loosening up” of the façade surface with a lace – is achieved, while the somewhat “flattish” quality is probably the author’s tribute of delicacy in the dialogue.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

Comparing the actual result to the project we see that a lot of details – for example, the ornamental grille, similar to the “Byzantine House” were discarded in the process, the carving became more exquisite, and the TPO Reserve façades on the yard side lost their relief elements.

As for the façades designed by Vladimir Plotkin, these, staying, as we remember, within the same color range, are quite different in many other respects, starting from the fact that most of the time they are dominated by horizontals, the windows being significantly more asymmetric and subjectivity agile, particularly so on the façades of the four-story buildings overlooking the Sadovnicheskaya Street. This is the main façade of this residential complex, and it demonstration of the diversity of the design solutions proposed by two different architects is probably particularly vivid here. Four different buildings stand in a row here, the second building from the left being the brick building of the XIX century, next to it standing the “fluted” section designed by Sergey Tchoban, the most “classic” of all four.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

On the sides stand the two sections designed by Vladimir Plotkin; they frame the dialogue of two historicisms, and, possibly, because of that they are subjected to the theme of a frame – not the simple kind but looking like a monochrome version of a composition by Pete Mondrian: the window grid takes up the entire façade, fitting into it like the fifteen sliding puzzle. The façades are smooth; white looks particularly white on them, and black particularly black, without any softening semitones. This is one of Vladimir Plotkin’s favorite techniques – black and white.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

At the same time, the new buildings on the street side also work in unison: all the three modern façades overhang above the sidewalk as three deep cantilevered structures, forming on top of them, as we remember, three terrace stairs, a phenomenon that is rather rare for Moscow. What it ends up looking like is a semblance of curios “noses”, with which the complex is “looking” over the street, as an offset to the brick building, old, self-sufficient, having seen lots of things, including the war and the revolution. This part of the complex – the four-story one with a terrace is, according to Vladimir Plotkin, the most dramatic one of all.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

In the outside façades designed by TPO Reserve, the piers grow a little bit bigger but the window – sometimes vertical, sometimes horizontal, and sometimes of the “constructivist” corner type – alternate in a lively asymmetric way. Here, on the outside contour, all of the window apertures got a black frame, the space between them getting stone ledges looking like the keys of some electric switches casting pointed triangular shadows and adding to the overall imagery of this “mechanism” building.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

Due to the fact that TPO Reserve got to design all the four corner sections, its architects also got to design more of the outside façades: the narrow stripe in the yard corresponds to the broad front on the outside street side. At the same time, however, Vladimir Plotkin designed the façade of the large central section, and now, upon closer inspection of the house in general, one starts to understand the role of the central risalit: it is a link which unites two themes: the meta-classic, decorated with grooves and carved patterns, the “blue blood” and statutory kind, dating back to the 1930’s – and the modernist, contrastive and dynamic, referring to the ideas of the 1970’s, although, if we are to speak of Mondrian, then to the 1920’s. The plastique controversy between the two main themes of the XX century, actually, grows through in the “white tree” of the central risalit. This is the final chord, an attempt to unite classics and modernism; it makes a resume of the dialogue and occupies a well-deserved central place.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

All of the hallway entrances are situated on the yard side, while the apartments that are on the first floors have their own individual entrances from the street; the first floors are also occupied by public zones, such as the inbuilt kindergarten and commercial premises on the street side. The yard has two levels in it; closer to the Sadovnicheskaya Street, there is a parking entrance ramp, and still a bit further on – a little park on its roof; the landscaping of the territory was done by TPO Reserve. The park has about a dozen rectangular flowerbeds in it, slightly raised above the ground level; some of them serve as podiums for trees: maples, limes, and even cherry trees. One of the rectangles closer to the center of the yard is occupied by a small fountain. All the flowerbeds have wooden benches around them, the curbs being made of brick. As for the paving, it is formed here by a textured carpet: it includes light-colored stone slabs, brick, spots of grass, and inclusions of wooden surfaces that turn the yard into a semblance of a terrace, a space that is homely and cozy.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Ilia Ivanov

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko

This way, what is happening in the yard is a closer interaction of textures which is not to be observed in the façades where the historic red brick and modern white stone are deliberately spaced apart. “Under one’s feet” brick is also to be found – it to be met in the space of the lobby, where the first fiddle is played by the stone, identical to the line that is used on the façades but livened up by inclusions of brick and wood.

The parallelepiped of the ventilation chamber, masked by an openwork grille of corten steel, takes on the role of an abstract sculpture, separating the park from the parking lot entrance, livening it up with us ruddy spot, also resonating with the brick façades of the loft building.

The landscaping work, the parking spots, the stone façades, and the moderate number of floors – all of this is determined by the expensiveness of the location that is “one traffic light away from the Kremlin” and the superb class of the housing offered. But then again, in Moscow, the architecture of such complexes, as a rule, maneuvers between the “conservative stylization with columns” (which is still more often is the case) and the “modern” type (which, although more rarely, but still does happen from time to time). And, basically, these are the two only options that you get to choose from. In this case, however, we have quite a different story: it’s not just that Tchoban’s ornamental architecture is not about stylization – in this instance, the dialogue between two established and recognized advocates of different stylistic paradigms became, at the client’s will, one of the chief narratives of the building. The discussion turned out to be a pretty mild one – it would be enough to visualize both opponents to realize that it could not have been otherwise – but one must admit that the very problem statement is very interesting.

"Wine House" residential complex. Photograph © Dmitri Chebanenko