Ivan Kramskoy, the architect whose pen was rather more accurate than his brush, wrote of the great Russian landscape painter Ivan Shishkin: “Shishkin is the milestone of the Russian landscape”. What he meant was that Russian landscape painting prior to Shishkin and after him were two completely different art forms. Before Shishkin the landscape was a respectable picture that hung above the desk in the study. After him it was an epic image of Russia, an object of national pride. Recalling this quotation, I could say that Nikolay Polissky is the milestone of Russian land art. Before Polissky land art in Russia was a series of experiments by fringe artists. But now, in his wake, it has become a matter of landscape festivals that gather crowds of people in their thousands. This is a fundamental shift in how modern art functions in Russia. And it is why I call him a milestone.

Land art in Russia has only a brief history. Essentially, Nikolay Polissky’s precursors were Kollektivnye deystviya [‘Collective Action’], a group led by Andrey Monastyrsky which existed from 1975 to 1989. There are few similarities between the two, and the differences are more important than the similarities. In the way it functioned socially, Collective Action was a fringe art group which treated its art as a variant of conceptualism and in its land actions drew on the traditions of zaum [an early-20th-century experimental movement in Russian literature] and the absurd. The special conditions governing the existence of art under the Soviet regime made this group an extremely important phenomenon: society was subconsciously based on the idea of a rigid vertical hierarchy of spiritual values, and the most hermetic art was perceived as the most elite. Collective Action was at the heart of the artistic elite during the final stages of the non-conformist period. But these artists represented the kind of art which is a priori comprehensible only to a small group of adepts and which constitutes a kind of ritual for the enlightened, a ritual which includes scripts for parodying both the ritual itself and enlightenment. To paraphrase a famous author, one may say of these artists that they were ‘terribly far from the common people’.

The unique shift carried out by Nikolay Polissky consists in a change in the way that art functions. His works are created by the inhabitants of the village of Nikola-Lenivets. This fact should not be overestimated: the ideas for the works naturally come from Polissky – it never occurred to the villagers themselves to build a ziggurat of hay or an aqueduct from snow. But at the same time it should not be underestimated. No one in the world has ever had the idea of crossing conceptualism with folk craftwork.

Two circumstances evidently played a role in this discovery. First, the artist experience of the Mitki group, of which Nikolay Polissky was a member in the 1980s and 90s. The artistic strategy of the Mitki may, at the risk of a certain amount of oversimplification, be described as conceptual primitivism. As is well known, the classical Avant-garde was in close contact with Primitivism (Henri Rousseau, Pirosmani). In my view, the Mitki tried to create what Primitivism could have been had it been based on installations, actions, and performance.

Primitivism is a step towards folk art. At least, it has absolutely nothing to do with zaum and absurdism. Primitivism emphasizes comprehensibility. But it is still some way from folk craftwork. Its simplicity is provocative: it is to be found in places where you wouldn’t expect it – in art of extreme professionalism. The simplicity of folk craftwork is natural and provokes no one.

In order to understand what kind of art Polissky does, you have to take into account the fact that he qualified as a ceramic designer. The experiments conducted by Russian arts and crafts during the Style Moderne period at the turn of the 19th century and by the studios at Talashkino and Abramtsevo are for him a kind of grammar-book, a natural guide to how to act. It’s this, I think, that explains the origin of the fantastic idea of combining folk crafts with conceptualism – it’s the kind of thing that you couldn’t invent; it could only come from real-life experience.

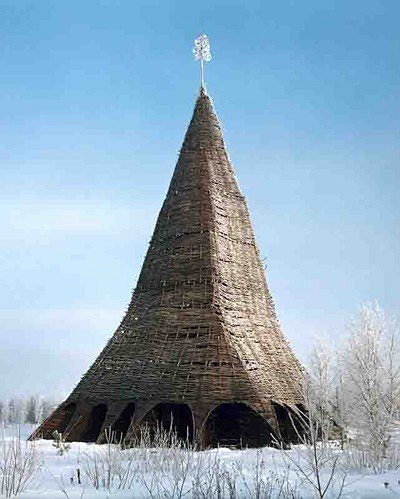

All the above is an essential prologue. For me the most important question is the content of this conceptual folk craftwork. Nikolay Polissky has constructed a ziggurat, an aqueduct, a medieval castle, a column resembling Trajan’s Column, a columned street like the one at Palmyra, a triumphal arch like the Arc de Triomphe, and towers resembling the Shukhov and Ostankino towers. These may not literally resemble their prototypes. It’s more as if the wind of rumour has carried word of these structures to the peasants of Nikola-Lenivets and they have built them exactly as they imagined them from these tales. These are archetypal architectural subjects, formulae for different periods in architecture.

Exactly the same subjects were in one form or another the principal subject-matter of ‘paper architecture’ in the 1980s. We find antique ruins, medieval castles, and majestic towers in the fantasies of Mikhail Filippov, Aleksandr Brodsky, Il’ya Utkin, Mikhail Belov, and other masters of paper architecture. I am not all supposing that Nikolay Polissky was under the influence of these architects; that would be absurd. But how can one explain his use of exactly the same themes?

Here I should say a few words on what was distinctive about ‘paper’ design in the 1980s. These were projects entered for competitions of conceptual architecture in Japan, where young Russian architects picked up several prizes each year from 1981 to 1989.

On the one hand, this was a continuation of the traditions of Soviet conceptual design – especially the Avant-garde, but also in part the traditions of the 1960s. Conceptual design is a myth of the Russian architectural school. Due to the fact that most designs by the Russian architectural Avant-garde were never built and yet had a significant influence on international Modernism, the traditional view in Russia has been that we have a very strong conceptual school. Paper architecture was founded on the persistence of this myth. However, there were important differences between this architecture and the conceptual architecture of previous ages.

Avant-garde conceptual design was closely bound up with the idea of a social utopia. In Russia today, following the renunciation of communism, people prefer not to notice this aspect of the architectural Avant-garde, regarding Constructivism as a non-ideological formal experiment. But this attitude significantly impoverishes Avant-garde architecture. All the characteristics of form that the Avant-garde sought – novelty, asceticism, and an explosive, alarmist architecture – came from the Revolution. Russian conceptual design by the Avant-garde was directly linked to social utopianism, and it is to this material that the term ‘architectural utopia’ in the strict sense applies.

In distinction to the above, the paper architects of the 1980s, due to the nature of relations between the late-Soviet intelligentsia and the Soviet authorities, felt a strong revulsion not just for the communist idea, but also for all social issues in general. In the paper projects of the 80s you can find all kind of ideas and formal scenarios, but you’ll almost never find in them any social pathos. These are not utopias, but architectural fantasies.

Fantasy is, of course, an activity which is unconstrained, but it has been noted that different ages fantasize in different directions. If we’re talking about the late-Soviet age, then for some reason the prevailing direction for fantasizing turned out to be the quest for archetypes and symbols, and for the most part these were drawn from the past rather than the future. Culture was interested in myths, ancient texts, and forgotten signs. Partly, this may be seen as a variant of Postmodernism, although in its approach to this subject-matter there were signs of a fundamentalism that was alien to the postmodern. Irony did not come naturally to this culture. This aspiration to discover certain fundamental bases of culture was equally characteristic of high humanitarian scholarship (work by Sergey Averintsev and Vladimir Toporov), elite cinema (Andrey Tarkovsky), popular cinema (Mark Zakharov), late-non-conformist painting (Dmitry Plavinsky), and stage design (Boris Messerer); it found its way into the most diverse cultural fields.

In my view, the installations of Nikolay Polissky are rooted specifically in this culture. It’s not the Shukhov Tower or a castle that Polissky builds, but the archetype of this tower or castle. The mysteriousness, symbolism, timelessness, and abstraction of his structures aligns them with the spirit of the vanished age of the 1970s and 80s.

It is this, I think, that explains the echoes of 1980s paper architecture I spoke of above. And it’s here that architectural history proper begins. After the end of the USSR, the character of Russian architectural life changed dramatically. Russia entered a construction boom that lasted ten years, and architects were snowed under with commissions; they ceased to be interested in anything beyond buildings. This spelt the end of Russian conceptual design. Essentially, the paper architects were the last generation of Russian architects who were interested in architecture as an idea rather than as practice and, above all, as business.

I think it can be said that it’s thanks to Nikolay Polissky that Russian conceptual design did not die. What is distinctive in the kind of conceptual design practiced by this ‘architecture beyond building’ (to use the phrase coined by Aaron Betsky) is not merely that it contains new ideas which go on to inspire real architecture. For the latter is usually not the case. Conceptual design does, however, clearly reveal what the architectural school lives by and what is the structure of its desires. And from this point of view, Nikolay Polissky’s works are incredibly interesting.

Let’s suppose that what we’re looking at is, first and foremost, conceptual design. What can we say of the school to which such concepts belong?

First, that it dreams of unique, fantastic, and incredible objects. Russian conceptual design continues, as during the days of paper architecture, to have little interest in social programmes, new models for solving the housing shortage, or quests for new forms of living. It dreams of building structures whose significance could be compared with that of Roman aqueducts, the ziggurats of the Near East, and crusaders’ castles. It dreams of buildings that are spectacular entertainments. This is a rare type of architectural fantasy – when architecture is engaged in thinking about itself, in a search for form. It dreams not of a new life, but of a fantastic and beautiful architecture that will take your breath away.

Secondly, I would say that the main problem for this school is a certain timidity springing from doubts about the relevance of its own dreams. If we are to talk of the works of Nikolay Polissky in architectural terms, then the main content of this work is concern for fitting a structure into the landscape. I think it’s this that allows us to talk of these works as architecture. Classical land art is, in general, not all concerned with such issues; on the contrary, it constantly introduces into the landscape that which cannot be and never was there – cellophane packaging, metal grass, sand and pebbles from the opposite hemisphere. Polissky fusses over his fields as if over his own children, carefully thinking up forms that will make an ideal fit with them and seem to have grown out of them. For Polissky to plant metal grass would be the same as to give a child a wig of barbed wire. “I dream of building a tower in such a way as not to wound the earth.”

Finally, we come to the third notable feature. If, again, we are to talk of Polissky’s works as architecture, then we cannot but notice that all these structures are essentially ruins. This is not an aqueduct, but a ruin of an aqueduct; not a column, but a ruin of a column; and not even Shukhov’s tower, but its ruin. In this respect, the aesthetic of Nikolay Polissky is closest of all to the architecture of Mikhail Filippov (see volume 1, p. 52). The deciding argument in favour of the appropriateness of this architecture is time: the structures are built in such a way that they seem to have been already there. The main claim to legitimacy of the architecture of this school is its historical rootedness; moreover this history is easily introduced into nature in such a way that virgin land instantly acquires a historical dimension measured in millennia – from the time when ziggurats and aqueducts were built here. I would say that if Western architecture today focuses on establishing where it stands in relation to nature, today’s Russian architecture is more interested in explicating its relations with history.

It is interesting that almost every important work of Russian architecture defines itself using this system of coordinates. The ideal formula for today’s Russian architecture is an incredible spectacle that is apt and at the same time rooted in history. The Church of Christ the Saviour and Norman Foster’s tower are equally embodiments of this formula. One could say that Russian and Western architects in Russia today compete with one another for the honour of embodying this concept.

All architects are familiar with the feeling you get when you arrive at a site and suddenly feel that the earth already more or less knows what should be built on it and what it dreams of. These are proto-images which although they do not yet exist, nevertheless have a kind of existence: they are hiding in courtyards, sidestreets, under archways or in the folds of the landscape, in the grass, or on the edge of the forest – in misty condensations of seemingness which have to be seen and listened to. The historian is forced to acknowledge that each age for some reason develops different proto-images, and if Le Corbusier everywhere saw machines for living in, Diller and Scofidio probably saw drops of mist. Some – a very few – of these proto-images are destined to sprout and be realized, but the majority will die without trace, and certain architects are very conscious of the tragedy of this death (see Nikolay Lyzlov, vol. 1, p. 41). Nikolay Polissky has learnt to pluck these images from the air.

Polissky translates into material form that of which the earth dreams here and now. This is not yet architecture, but nonetheless it is a relatively distinct statement of what architecture should be. It should be breathtaking. It should make an ideal fit with the landscape. And it should look as if it has always stood here and is even slightly dilapidated.

The author of the present text first met Nikolay Polissky in 1998, when the Mitki group of artists, together with Sergey Tkachenko (see our volume entitled ‘Russian architects’, p. 51), organized an action called ‘The Manilov project’. The point of this event was to declare the urban-planning programme then being conducted by the city of Moscow a realization of the dreams of the landowner Manilov from Nikolay Gogol’s Dead Souls (fantasy in the purest form, unconstrained by pragmatism or responsibility of any kind). “He thought of how wonderful it would be live as friends; of how good it would be to live with a friend on the banks of some river or other, over which his mind began building a bridge and then an enormous house with such a high belvedere that it was even possible to see Moscow from there and drink tea in the open air in the evening and reflect on pleasant things.” This was a moment of rare friendship between architects and artists: afterwards Sergey Tkachenko became Director of the Institute of the Master Plan for Moscow, i.e. in effect began shaping Moscow’s urban-planning policy; and Nikolay Polissky set off for the village of Nikola-Lenivets to realize his unique art project. But this historian is glad to discover that they set off from the same point in space and that he even had the fortune to be present at their point of departure.

Since 2006 the architecture festival ‘Arch-Stoyanie’ has been held annually at Nikola-Lenivets. For three years in a row the leading Russian architects have travelled to Nikolay Polissky to create installations in the same spirit as those made by Polissky himself. It cannot be said that their creations are exactly successful; as yet they are artistically vastly inferior to Polissky’s. But they do try, and this in itself is unexpected and intriguing. Polissky plays the role of artistic guru in today’s Russian architecture. This school is, at any rate, very distinctive. It has its own conceptual design, but this design exists in a slightly unexpected field. I think Piranesi would be extremely surprised were he to learn that the genre of architectural fantasy which he discovered has in Russia become a folk craft.