Alexander Skokan. Photo © Aleksey Nikishin

Archi.ru:

- What is your concept all about?

Alexander Skokan:

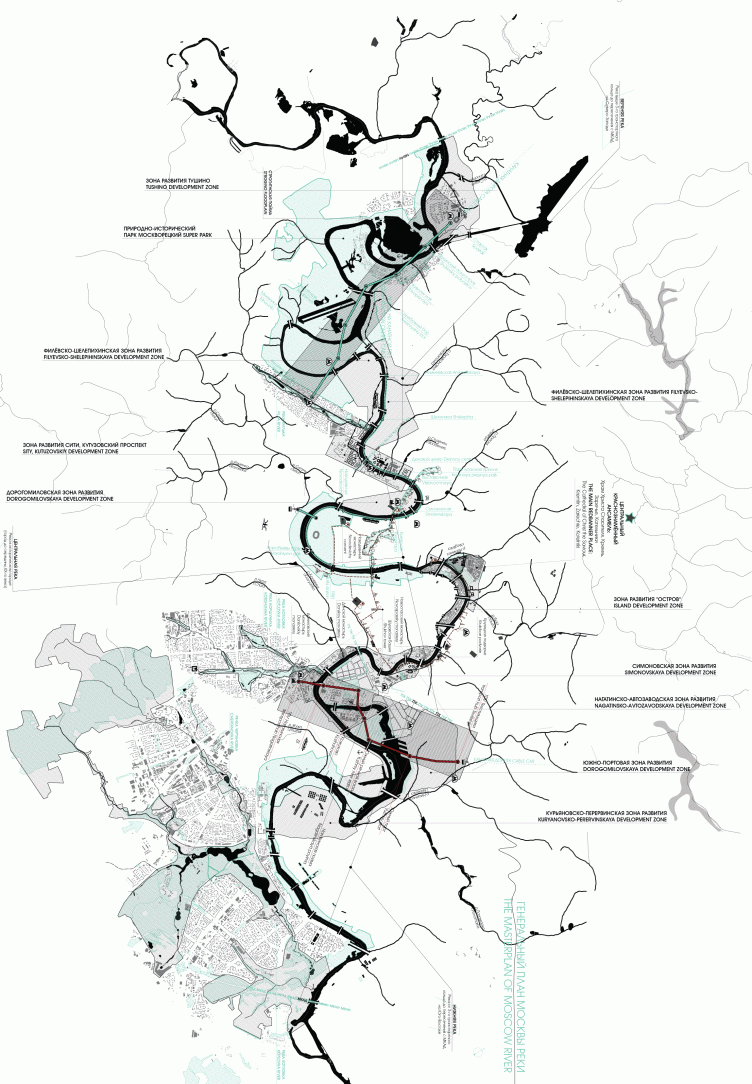

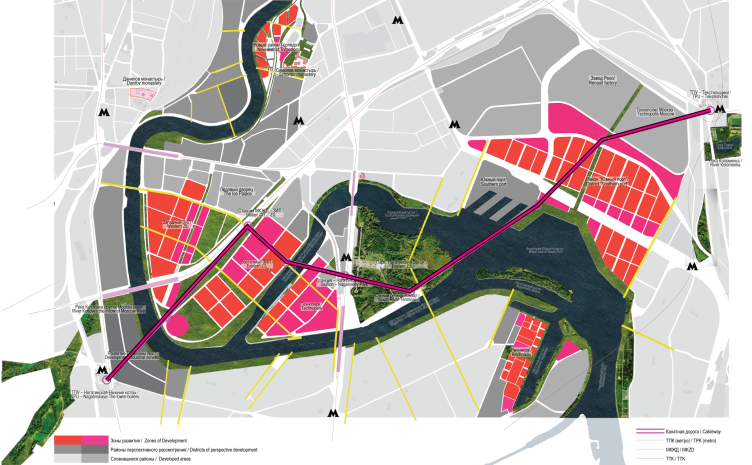

- Actually, the river is more of a negative factor than a positive one. It tears the city apart just like the railways do, or the Third Transport Ring or the industrial parks. Our idea is all about turning it from a divider into a connector - some sort of a longitudinal bridge that would pass through the city and pull it together.

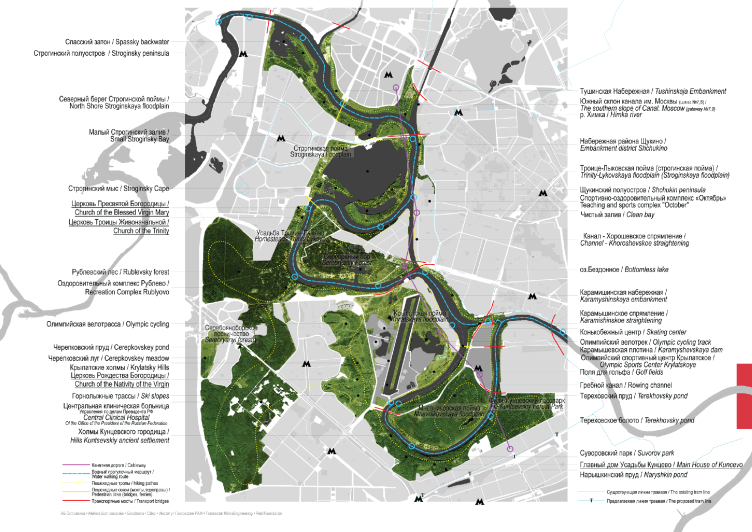

The functions, of course, must not be uniform - this is not a linear corridor. Try to think of the river as a string of beads: a blue thread that various beads are strung upon: Kremlin, Gorky Park, monasteries, Christ the Savior Cathedral, and House on the Embankment are totally different gravity centers - the rivers ties them all together into a single whole.

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Inventory: functional and typological layout. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Still, this not all that you can say about the river. It is about five hundred kilometers long, it begins in the swamps and spring-wells near the city of Mozhaisk and then grows stronger; on its way, it meets the city of Moscow that - let's face it - does a great deal to uglify the river, although the megalopolis still remains the main event of its life. After meeting the city the river "brushes off the dust" and recovers along the length of one hundred and fifty kilometers and finally flows into the Oka, dissolves in its flow, and dies becoming a part of something greater (one should say that any river is very metaphoric). In a word, a river is a living being.

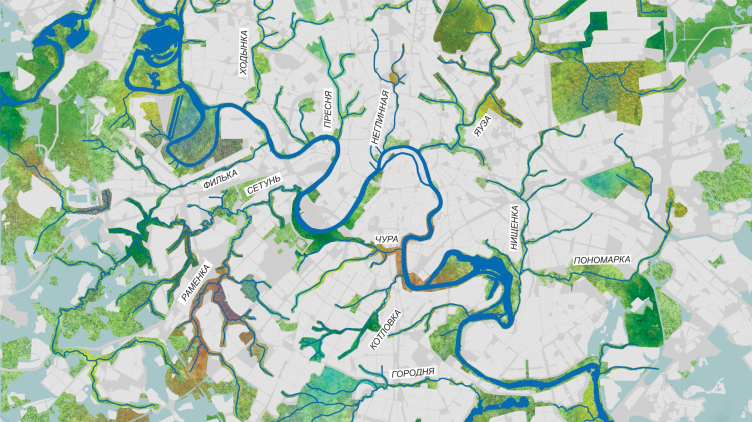

And you cannot really treat it as some abstract environmental system: the Moskva River is not a pipe that runs through the city clad in granite or something of this kind. The river only exists with its numerous affluents that nourish it it and that constitute a single whole with it. We know Neglinka, Yauza, Skhodnya, and Setun; we know of no other rivers, and within the confines of the city there are about one hundred and forty of then - rivers and brooks that the city kept pushing underground as it continued its expansion. The river can only be healthy if all of its affluents are healthy. The territory that is covered by the contest specifications is no more than a ninth part of the city; the other eight ninths are left totally unattached. Meanwhile, if we do pay attention to all these little rivers, however small and insignificant, we will get a system that embraces the whole city and influences Moscow's entire territory.

Thus, the message that we wanted to get across was that, besides the improvement of the riverfront, that Moscow is actually quite successful in - take the embankment before the House of the Artists, for example - it is necessary to recall not only what this river is like but its whole basin of a hundred and forty rivers as well. If we understand just what to do with them and what exactly we need them for, we will ultimately get a different city: more eco-friendly, healthier, and, I would say, more valuable.

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

- Were the affluents in any way present in the contest specifications?

- No, they weren't. The consideration of the river-basin is completely our initiative. Probably, this is the characteristic feature of our team - we would rather expand our task than narrow it, we try to see the "off-screen" things. We were asked about the river corridor, and we discovered that the river grows into the territory of the entire city with its tentacles.

- So, what solutions were proposed by "Ostozhenka" for Moscow's minor rivers?

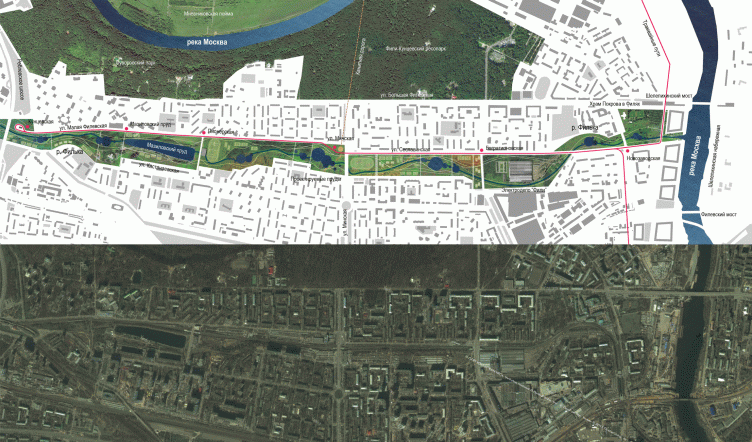

- As an example, we took three affluents: Filka, Kotlovka, and Gorodnya - and gave them a more detailed consideration. Take the Filka River: upon it, there had stood the settlement of Khvili, then, later, during the soviet times, the district of Fili-Davydkovo; in the fifties it was routed into a pipe and a subway line was built above it. Now this subway line is surrounded by a fence and a right of way; it dissects the neighborhood in two. We actually proposed to do away with the subway line - all the more so because this prospect is already widely discussed, what with the fact that the Filevskaya Line doubles the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya line and its workload is pretty slack - open up the river, make a park around it, and run a low-floor tram along it - the low-floor tram will relieve the workload of the Filevskaya line but it will unite the area instead of dissecting it. We will open up the river to the city; and the city will be able to come out to the river. We will enhance the beauty of the Naryshkino Holy Protection church built on the cape where the Filka flows into the Moskva River. The junction capes are extremely important; they are the town-planning accents, at one of such capes, the Kremlin rests, and they must be treated with care and respect.

Proposal of developing the Filka River. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Proposal of developing the Filka River. "Before" © Ostozhenka

Proposal of developing the Filka River. "After" © Ostozhenka

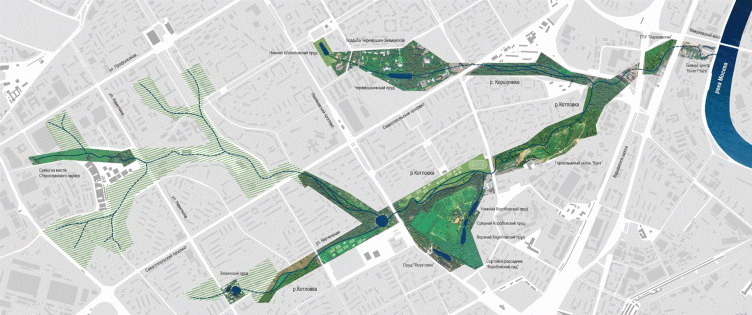

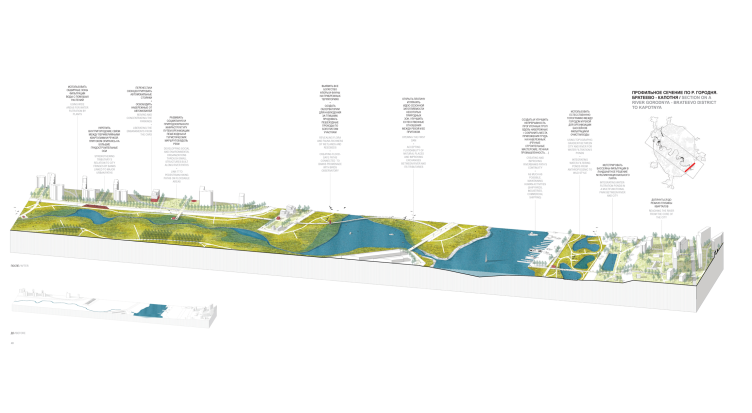

Another example is the Kotlovka River at the southeast of Moscow, at the land of the proverbial giant power plants. Everybody who has ever driven down the Varshavskoe Highway or the Sevastopol Boulevard knows the descents and the ascents of the road that are especially tricky when the roads are slippery in the wintertime - each set of traffic lights is preceded by a hill that is actually formed by the banks of the Kotlovka that flows underground. Only partially piped underground, this little river shows up in the city in a punctured line forming separate parks; on one of the river's banks there's even a ski slope that is rather popular in Moscow. At some places it is the other way around - there might be a house physically standing on the river, smothering it. Meanwhile, it is a quite realistic idea to tie all the existing fragments of the parks into a single system, stringing them upon the river. The third example: the Gorodnya River that actually nourishes the Borisovo and the Tsaritsyn ponds - it springs from the district of Yasenevo, the Bitsa Park, and then in Brateevo it flows into the Moskva River. This is the place where people go fishing on the weekends, living in tents - all these recreation areas can be developed and taken to a new level. We showed these rivers as examples; they are not the answers, they are the new questions, really.

Proposal of developing the Kotlovka River. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Proposal of developing the Gorodnya River: the southern analogue of the Moskvoretsk Park. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Profile section along the Gorodnya River. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Today, the minor rivers and headwaters live very different lives: some of them are getting along quite well, for example, the Likhoborka River on the northeast of the city. Others, on the other hand, are almost completely neglected like the Nischenka Creek that flows through the industrial parks in the east of the city in the underground sewer. There are also rivers that have been completely buried underground and rivers that have virtually disappeared - we do not propose to revive them all, which would make little sense. However, it has been noticed that even if the river is no longer there the vegetation is still greener in its former floor land, and the trees grow better - such places could become the basis for new parks or eco-trails. One of such derelict rivers used to flow into the Yauza in the neighborhood of Art-Play complex. The northern "green ray" in Stalin's master plan was also connected with the rivers - Neglinka and others.

You see, the Moskva River is already talked about, and, since the contest is already announced, it means that the idea has taken root. The riverfront will be improved, one way or another. We thought it important, however, to push the limits of the discourse and remember the fact that Moscow has in it 141 other rivers.

Our proposal is about the following: the Moskva River is the city's or even the nation's high-profile cause. We, however, search in every district for the opportunity of creating an area for the local recreation - so as to avoid the prospect of the whole city trooping at once to make a huge waiting line in the area of Gorky Park on the weekend. And, on the other hand, such local improvements could go a long way to foster the local patriotic feelings: my house, my land, my Kotlovka. People themselves could participate in the planning and implementation, and this would take the whole idea of local self-regulation to a totally new level.

- Do you think that self-regulation of the population is at all possible?

- I think we should look for reasons to raise social awareness, and people's awareness of geographic landmarks in particular - such as the local rivers, they could be a great reason to start with.

- Your network of parks around the rivers looks like a post-industrial eco-city. Is it opposed to the current industrial city?

- The way we see it, inside the megalopolis, there is not one but several cities superimposed on one another; at some places they exist independently, at some - interact with one another. We do not always remember about their existence, and now we are gradually discovering them. Today, within the framework of this contest, we speak about the zones that are attracted to the river and about the riverfront as a fragment of the urban matter. But then again, there is also the "railroad" city with the giant rights of way and giant railway yards in the neighborhoods of the Rizhskaya metro station. So now we day that there is yet another city - the 141 rivers flowing inside of Moscow.

Looking at the map of Moscow of the middle of the 19th century, one can plainly see that a lot of important city events were connected with large and small rivers - and not only in the villages near Moscow that naturally stood upon these rivers. In the late 19th century, the railroads were also often built along the river beds because a significant part of the city had already been built and the best vacant places had already been occupied. Why do you think the Nikolaev Railroad - for which it would have made perfect sense to run along the Tverskaya Street and down to the Byelorussky Railway Station - stops short at the Kalanchevskaya Square? Simply because it was routed to a problem swampy land site full of small rivers and brooks. The Paveletskaya Railroad is also a buried river. The Filka river that was filled in by a subway line back in the soviet time is not the only example; in the XIX century, the riverbeds were already used in such a way.

Moscow is a complex superposition of different themes and different "cities". The medieval Moscow never did overlook the river, let alone have a decent embankment. And then, on the Yauza, there appears the Foreign Quarter - a place that's totally different. The foreigners were sent to settle at a distance from the rest of the city so as the Muscovites would communicate with them as little as possible. In any case, during the days of Peter the Great, the Foreign Quarter did not look like Moscow at all, it was rather a prototype of Saint Petersburg - and the river is treated quite differently in Saint Petersburg. In the medieval Moscow, the river was an annoying obstacle but in the Foreign Quarter it becomes the center of attraction - it is overlooked by the Golovinsky Garden and by other palace parks with their ponds and creeks, as well as aqueous events...

In the soviet times, according to the same principle, there was built the World Trade Center, and all the foreigners were gathers there, also with a view of controlling them. It also stands on the river.

And finally, when the architects were looking for the place for the Moscow analogue of Paris's La Defense (the business center), it was also found on the river, wedged between the Testovskaya and Shelepokha platforms. In the early eighties, when Boris Tkhor advocated this idea, there were mainly garages there - this place was virtually not known to anyone - and there were two integrated house-building factories that the city easily lost to provide the territory for the business center. Back then, I was working in Scientific-Research and Design Institute of the General Plan of Moscow, and we as early as at that time would say that Moscow is not Paris, you cannot make do with just one business center; what you need is a chain of such centers. But in other places there were numerous land issues - for example, at Rizhskaya, the Moscow railroad was not ready to give up its land for such a project... And we ultimately got what we got - some sort of an abscess that warps the whole city.

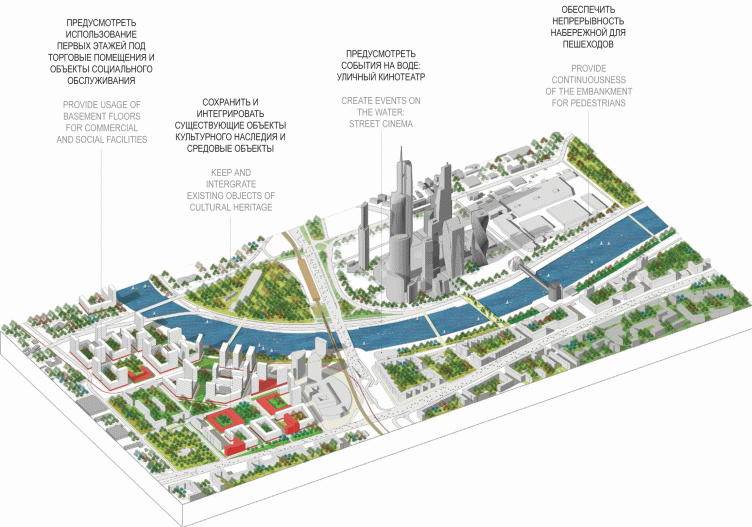

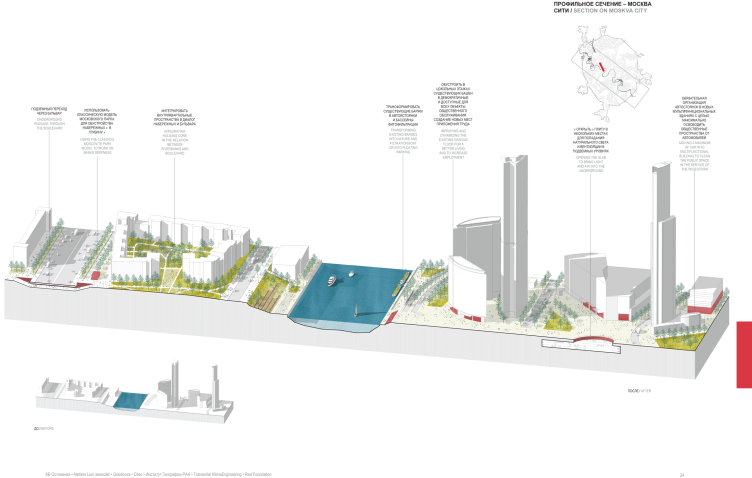

- You recently proposed to add new bridges to Moscow City, didn't you?

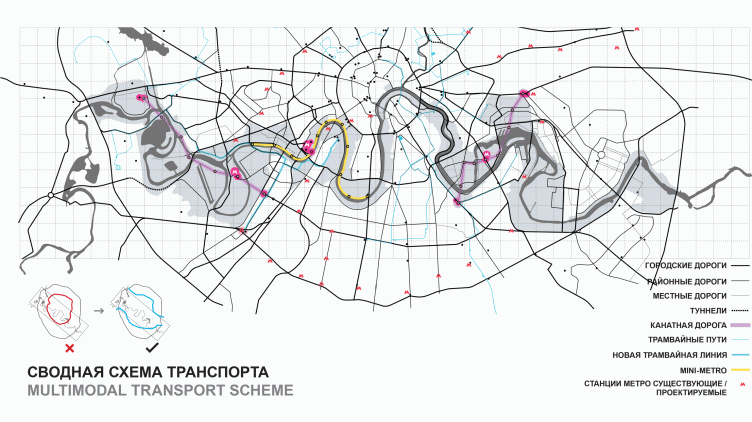

- Yes, we proposed to connect the two banks, catching the right bank with the "border hooks" of the bridges, two more to relief the Bagration Bridge. Because it is on the right bank, only some three hundred meted away from Moscow City, the Kutuzovsky Avenue is situated - a full-scale thoroughfare with great architecture, retail stores on the ground floors, the highly developed city center. If we provide a better connection between the two river banks, we will get a full-scale urban unit that would offset Moscow City. Besides, we proposed to create on the right bank a promenade, and to improve the transportation aspect of the left bank by building a line of sky train there.

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Profile section of Moscow City. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

The area of the World Trade Center of Moscow City. The stages of the project implementation. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

- Are there many new bridges in your project?

- Generally speaking, the more bridges the city has, the better off it is. We, however, showed in our project that besides the usual pedestrian and traffic bridges, there can be overhead bridges, and passenger cableways, like in the mountains or on ski slopes. Two years ago such a cableway was built over the Volga - at a hundred meter altitude it connects Nizhny Novgorod on the right bank and Bor on the left. In the Columbian city of Medellin over the favelas, there are several such cableways built over the hills.

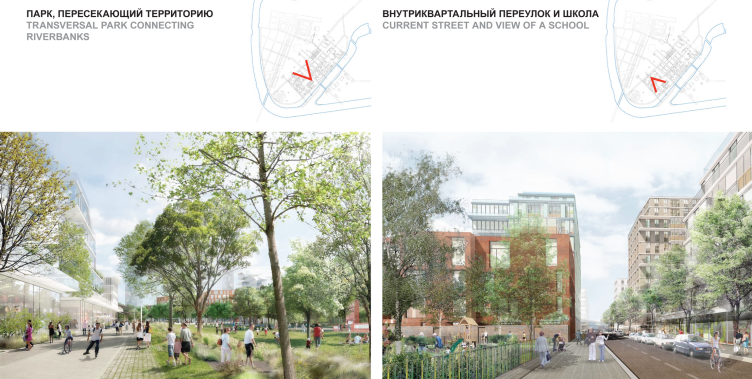

In Moscow, we found at least two places where such cableways could be built: one line would connect the "super-park" of Krylatskoe, the Strogino forest, and end in Tushino. The other route - from Nagatino to the ZIL peninsula to the Nagatinsky Park metro station which is still under construction. Thus we would connect the separate fragments of the city. Such cableways can go over the buildings, over the trees, and over the river, simply connecting point A to point B with a straight line. What one will need is just the supports standing each two or three hundred meters. This is a high-capacity kind of transportation and at the same time a great tourist attraction.

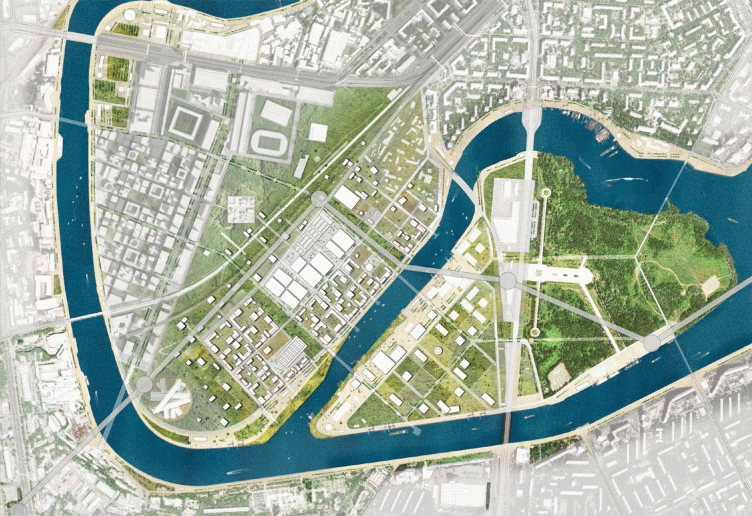

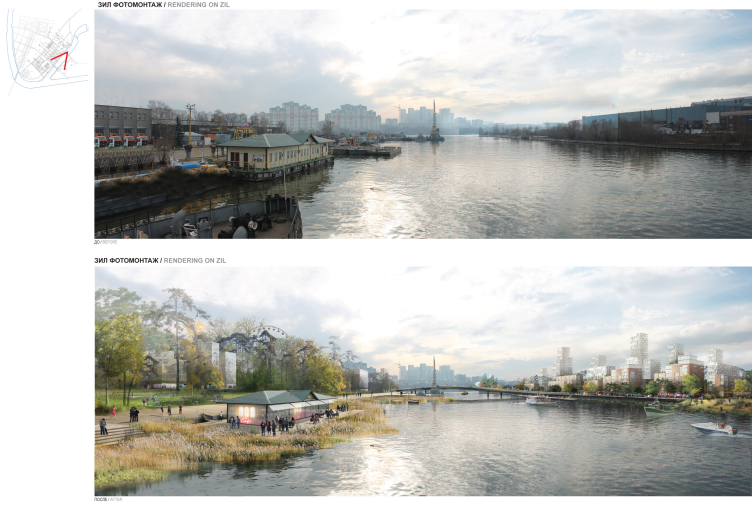

ZIL Plant. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

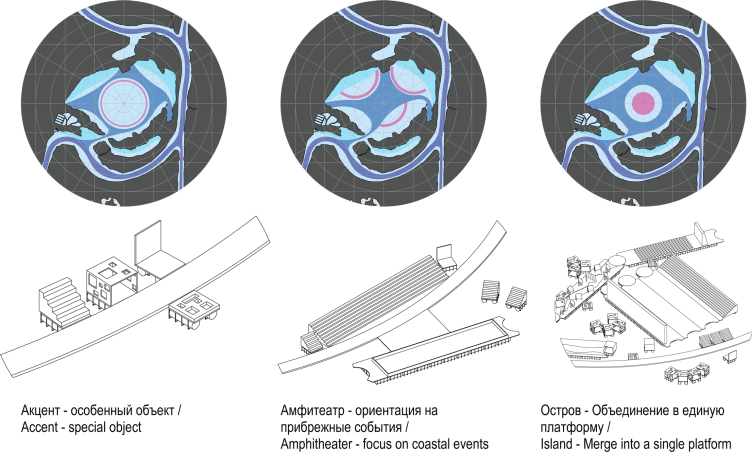

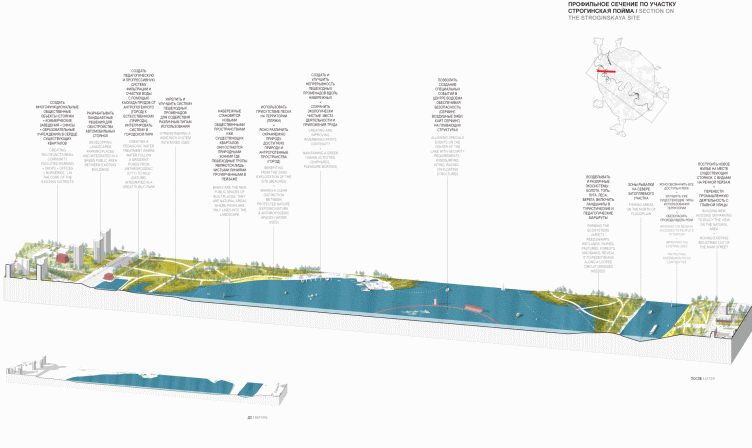

Serebryany Bor and Strogino flood land. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

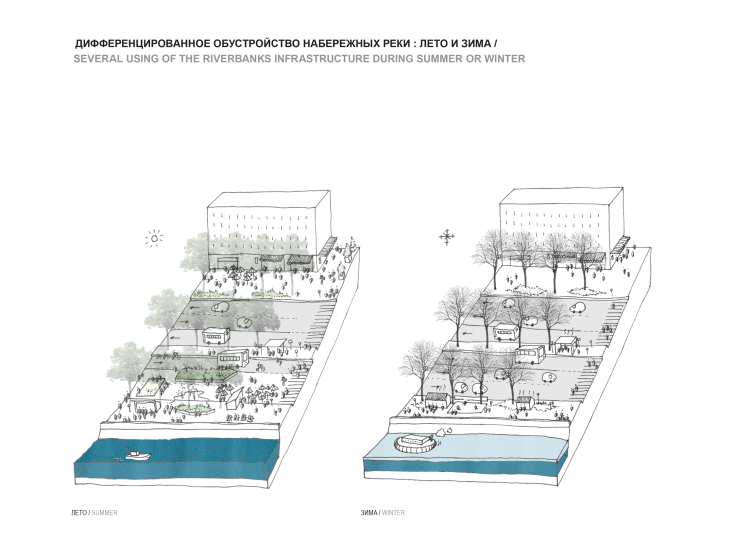

Improvement of the embankments in the summer and in the wintertime. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

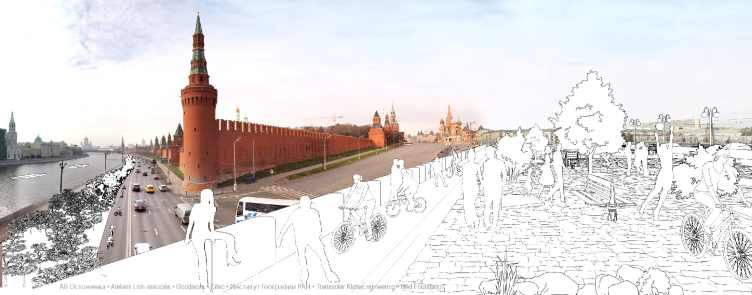

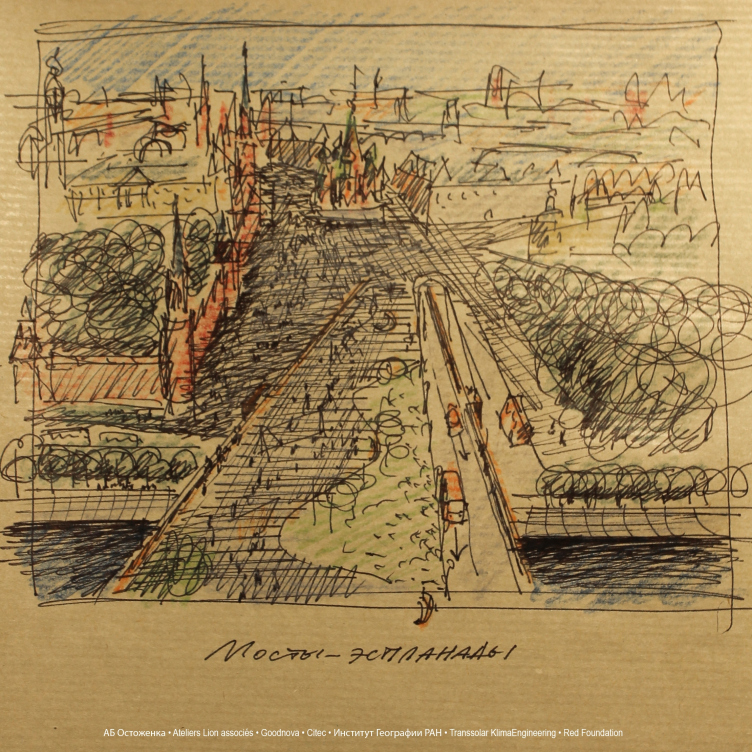

The esplanade of the Moskvoretsky Bridge as the continuation of the Red Square. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

The esplanade of the Moskvoretsky Bridge as the continuation of the Red Square. Sketch. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

- This all has to do with the passenger transport, and what fate do you prepare for the drivers? You are closing all the embankments for the automotive traffic, aren't you?

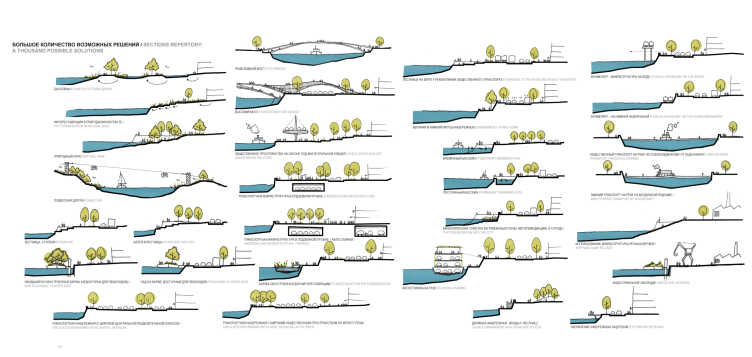

- The thing is that the embankments of the Moskva River became only open to automotive traffic in the thirties and forties. What we are proposing is not to close them altogether but reduce the number of lanes at the same time broadening the sidewalks - besides, we make an important reservation that this can only be done after taking a number of measures, including unpopular ones, otherwise the traffic will simply collapse.

- What unpopular steps must be taken, from your professional standpoint?

- A fee-paying vehicular entrance to the city center within the Third Transport Ring, for the exception of the residents, of course. As far as the territory beyond the Third Transport Ring is concerned, we must make it more cohesive and chord-line roads; there is enough room for building new road junctions here. Many things are done by this city in the "catch-up" mode: the broadening of the highways and the construction of the flyovers should have started about twenty-five years ago; now it is next to impossible to catch up.

- I remember you saying that two months is not enough to work on a concept of such magnitude. And how much time would you need for normal serious work?

- At least half a year. Now we have just about had the time to "cast away the stones", and not all of them, either. We've had no time to gather the stones, though.

- In this case, how would you describe the specifics of your concept? Its genre, if you like?

- I think of this work as the invitation to a discussion. A lot of questions arises here - I would even sort them out into three categories: financial, administrative, and social... And I think that one of our tasks is tying all these questions together for the future master plan. I would call this an exercise in considering the city's issues, an search for the structural regularities and consistencies.

In the Russian culture, there is a phenomenon of "obretenie" that can be translated as "attainment", "uncovering" or "appropriation": it is all about finding something that was around all along, only you did not notice it earlier. It might sound too self-assured but two years ago the "uncovering" of the Moskva River took place thanks to, among other things, to our company taking part in the contest "Big Moscow". And I would be happy if the city ultimately - through our efforts - uncovered its minor rivers. Incidentally, in 2004, the Scientific-Research and Design Institute of the General Plan of Moscow issued Decree 666: the ecologists and the geographers counted all the minor rivers, prescribed what to do with them, and calculated their improvement expenses... You can look it up online - this decree has no power, which comes as no surprise, with such a number! In other words, everything was invented before us, we only had to recollect and revise it.

- What do you think is the most important thing in implementing one's contest proposals and concepts?

- Any reservoir must be viewed as a whole; the river is first of all a flow; it crosses the borders of a whole number of territories; a river cannot be divided, for example, between the Central Autonomous District and the Southern Autonomous District; it cannot be tidy in one place and neglected in another. What you need is some structure that has the authority to coordinate everything that has to do with the city's rivers. Today, one agency deals with the public water supply, another - with the navigability, but what agency will deal with everything that has to do with the contest? Should we create the Ministry of River? And then the Ministry of Minor Rivers? I've got no answers to these questions, I am rather asking questions.

***

The project was developed in consortium with the architects and urbanists of Ateliers Lion Associes (France), architect and urbanists Alexandra Goodnova, and geographers and ecologists of the Institute of Geography of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The transport issues are curated by Yuri Shershevsky and Citec Company headed by Philippe Gasser. The cultural programming and the economic model was developed by Red Foundation. The ecological concept was designed by Transsolar KlimaEngineering.

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Strogino flood land. Dry land plan. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Profile section along the Strogino Flood land. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

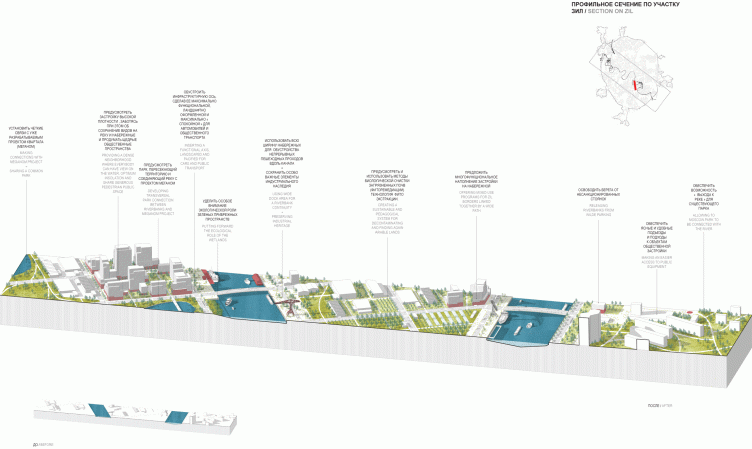

Profile section along the ZIL Plant. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

ZIL Plant. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Development of the territory of the ZIL Plant. Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka

Concept of the riverfront development of the Moskva River © Ostozhenka