The Sytin House restoration project. The main facade 2019

Copyright: Photograph © Andrey Milevsky

It so happens that we are examining already the second “Sytin Mansion”, whose restoration project was developed by Ginzburg Architects. For clarity’s sake, it must be noted that neither the houses, nor the namesakes were related to each other in any way. The first house was the editorial building of the “Russkoe Slovo” (“Russian Word”) newspaper, built by its publisher, Ivan Sytin, and later restored in 2008-2015, situated in the so-called “Izvestia Quarter”. Back in his time, Sytin bought out almost the whole of this chunk of land, including the plot belonging to the merchant family of the Lukutins, where he decided to build a house that would combine the functions of the editorial office and the private residence of the newspaper owner. The building was designed by the then-fashionable architect Adolph Erichson in the style of an Art Nouveau tenement. It was this building that was in 1979 moved on carrying rollers during the construction of the new Izvestia editorial office.

The Sytin House restoration project

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Knyazev / Ginzburg Architects

However, the house that we are going to examine below is a different one – it is situated at the other end of the Tverskaya Street, Sytinsky Lane, 5, not far away from the crossing with the Bolshaya Bronnaya Street.

The Sytin House restoration project. Photograph of the main facade, the 1900′s

Copyright: The materials from “Historical and cultural survey” / OAO Tsentr Kompleksnogo Razvitiya

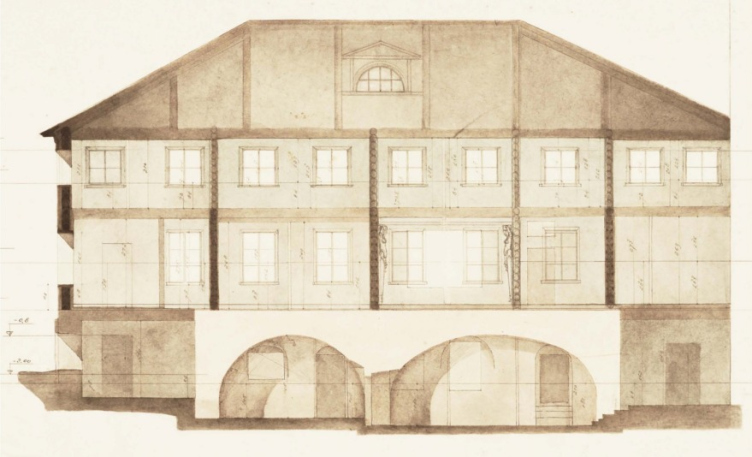

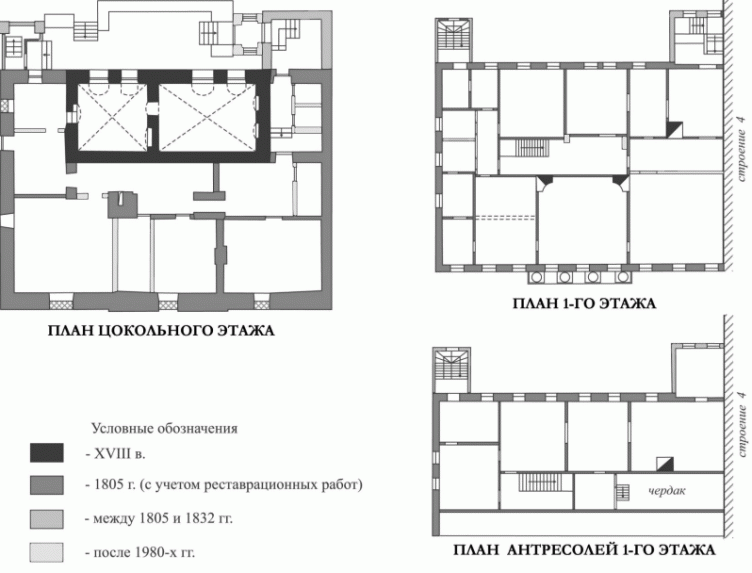

The history of this house dates back to the XVII century and earlier. Suffice it to say that the house in question was built upon a derelict stone foundation that was a vaulted basement of ancient storage chambers of late XVII century. These were situated somewhere in the depth of the estate because at that point in time the Sytinsky Lane did not yet exist. The Sytins owned this strip of land for almost the whole XVIII century; then, at the turn of the XIX century, the estate was divided into three parts among the heirs. The East part, running along the Sytinsky Lane, went to Major Alexander Petrovich and Brigadier Andrey Petrovich Sytins. In 1804-1805, they built here a single-story wooden house with a mezzanine, building two stone (!) wings on the sides, with their ends facing the lane and thus marking the borders of the estate. One of them, the left-hand one, survived into the present – it is now painted yellow. Another surviving construction is the carriage barn – also a part of the former estate. And, in the stead of the other wing, in the early XX century, a four-story tenement was built, designed by Sokolov, for which they dismantled a side wall of the log construction.

The Sytin House restoration project

Copyright: The materials from “Historical and cultural survey” / OAO Tsentr Kompleksnogo Razvitiya

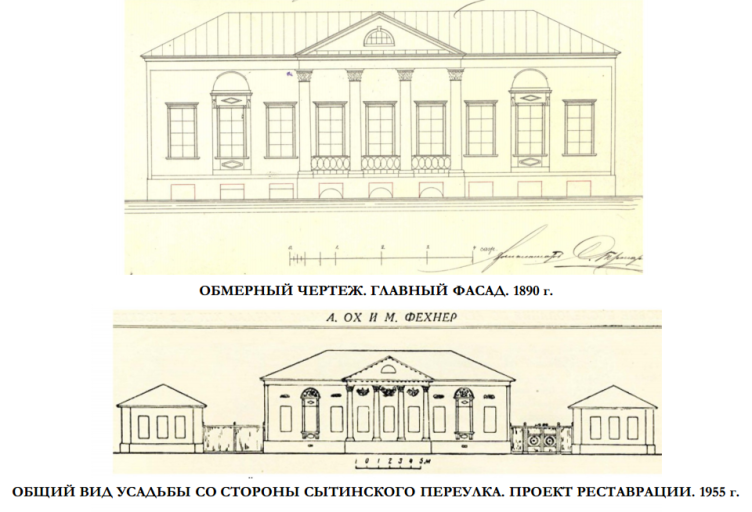

The brigadier’s house was built on a budget that was not the richest one but not the tightest one either: it main facade, 21.81 meters long, features nine windows. The building is a single-story one – for fire safety reasons, building any higher was not allowed, the lack of premises being compensated by the loft on the yard side. Composition-wise, this estate is typical for its time – the overall size of the house and the facade proportions were regulated by a special city committee. On the outside, the log construction was covered in wooden boards and painted, the main facade liberally decorated with plasterwork. The mezzanine rests on a Corinthian portico, the windows being adorned by stucco decorations of four different types. The central element – the Gorgon’s head – was recreated by the historical drafts because by the time the restoration started it was already lost. The other motifs of the plasterwork, such as decorative garlands, cornucopias, and total absence of symbols of defeating the Napoleon army, serve as yet another proof of the fact that this house was built before the great fire of Moscow of 1812. This is also evidenced by their abundance – in the empire-style Moscow of the epoch of Bove, Gilardi, and Grigoryev, these elements already went out of fashion.

The Sytin House restoration project. The measurement drawing. The longitudinal section, 1955

Copyright: The materials from “Historical and cultural survey” / OAO Tsentr Kompleksnogo Razvitiya

The Sytin House restoration project

Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects

The yard facade is much more modest – what decorative elements it has are carved window frames. The entrances to the building are situated in the yard “projections”; the north-west one has a porch attached to it. The mansion has a roof of steep pitch; above the side and the yard facades, one can see semicircular gable windows underneath triangular frontons. The staircase lobby used to be lit by a special skylight upon the roof, slightly shifted off the central axis.

The Sytin House restoration project. Construction periods, 2016

Copyright: The materials from “Historical and cultural survey” / OAO Tsentr Kompleksnogo Razvitiya

Surviving, by a sheer stroke of luck, the Fire of Moscow 1812, the house then changed several owners without any significant changes made to it. And, although not the whole of the manor house survived into the present, the house did live to show us its unique authentic architecture. This was also helped by the fact that in 1960 this house was granted a protected status as a cultural heritage site of federal importance.

The Sytin House restoration project. The photograph before the restoration, 2016

Copyright: The materials from “Historical and cultural survey” / OAO Tsentr Kompleksnogo Razvitiya

The restoration, the first during the entire history of the house, was performed here as late as in the 1980’s. Up until that moment the building stood idle for two decades, rotting away and disintegrating because of the leaks. Looking at the photographs of those years, we can see that the restoration workers fully restored the facade, including the lost fronton and all of the decoration. The research also evicted the original terra cotta color of the paint. Judging by the absence of any other layers of paint underneath the plasterwork, one could come to a conclusion that generally it is contemporary with the building’s construction, even though some of it was lost, and some added.

The Sytin House restoration project. The photograph before the restoration. The yard facade, 2016

Copyright: The materials from “Historical and cultural survey” / OAO Tsentr Kompleksnogo Razvitiya

The problem with the 1980’s restoration, however, was that at that moment the Soviet restoration school was ruled by the “stylization approach” – i.e. some image of the architectural monument at a given point in time was restored, regardless of compromising the authentic structure of the building. This led to a loss of a few elements. For example, restoring the facade of the earliest possible period, the restoration experts made the window apertures on the level of the basement floor. However, on the yard side, the annexes were not dismantled.

The Sytin House restoration project. The yard facade 2019

Copyright: Photograph © Andrey Milevsky

The Sytin House restoration project

Copyright: The materials from “Historical and cultural survey” / OAO Tsentr Kompleksnogo Razvitiya

Nevertheless, by the moment of the last restoration, the house did preserve a number of authentic elements, which were carefully studied and restored. As for the log construction itself, according to Aleksey Ginzburg, thankfully, it did not require overhaul – the restoration workers just repaired it in a few places, partially replacing and reinforcing the damaged areas of the pinnacles. Other things that were restored were the wooden wall sheathing and the stone-white basement; partially replaced or completed were the bases of the columns. All of the seven windows 1890 included in the previous restoration project were also restored. Now they are covered with metal window crates made by historical drawings. Some of the plaster decor of the facades was restored, some made anew by the molds.

Special attention was paid to the most ancient part of the construction – the vaulted chambers of the XVII century: the restoration workers uncovered the stone-white floor and the vaults in the basement floor. Interesting is the fact that the elevation of the floor was actually lowered based on the field survey, while the removed slabs, treated with protection chemicals, are laid at the historical elevation. The architects opted out of painting the disclosed brickwork, and one can tell the modern repairs by their color.

At the moment preceding the restoration, the inner floor plan of the building was kept within the limits of the bearing walls and partitions or the first third of the XIX century with adding a few partitions after the 1980’s. Barring a few additions, this is the floor plan that we are seeing now. The house was built with a clear division into the grand, residential, and auxiliary premises, characteristic of those days. The high-ceilinged rooms of the main enfilade were situated along the grand facade, the lower rooms along the yard side. The main staircase underneath the skylight, leading to the second floor, was originally slightly shifted in respect to the central axis. There were another two staircases in the yard risalits.

The vaults of the XVII century. Left: view before 2016. Right: view after the restoration. The Sytin House restoration project.

Copyright: Provided by Ginzburg Architects. Photograph 2019 © Andrey Milevsky

What remained of the authentic elements of the interior is not a lot – mostly, the furnaces that in the 1980’s were recreated from the historical tiles in their original places, and the sculptures of Caryatids, supposedly, from the mid XIX century.

“The interiors above the basement are, of course, newly-made – Aleksey Ginzburg shares – We recreated them by historical samples: the parquet pattern of those days, wall decoration, and so on. Our project, based on historical analogies, thoroughly recreates all the woodwork around the house – the windows, and the braced doors that were made by the original drafts that were kept in the archives of the 1980’s restoration. We did a very thorough job of studying the details, which we always enjoy very much.”

Interior of the central room on the first floor. Left: view before 2016. Right: view after the restoration. The Sytin House restoration project.

Copyright: Provided by Ginzburg Architects. Photograph 2019 © Andrey Milevsky

Another thing that was restored was the glued-laminated parquet on the first floor. The attic floor coverage was made from wood boards by historical analogues. The architects also slightly changed the location of the skylight above the staircase and the gable windows on the roof, which now match the archive data. They also restored the lost splays and the beautiful braced doors, and cleared and restored the stucco of the inner wooden walls and ceilings.

The attic floor. Left: view before 2016. Right: view after the restoration. The Sytin House restoration project.

Copyright: Provided by Ginzburg Architects. Photograph 2019 © Andrey Milevsky

The central staircase and the skylight. Left: view before 2016. Right: view after the restoration. The Sytin House restoration project.

Copyright: Provided by Ginzburg Architects. Photograph 2019 © Andrey Milevsky

The double door in the grand rooms. Left: view before 2016. Right: view after the restoration. The Sytin House restoration project.

Copyright: Provided by Ginzburg Architects. Photograph 2019 © Andrey Milevsky

Caryatid. Left: in the process of restoration. Right: after the restoration. The Sytin House restoration project.

Copyright: Provided by Ginzburg Architects. Photograph 2019 © Andrey Milevsky

The adjustment project included installing the necessary engineering systems in the building, such as metallic pipes of the air shafts, a heating system of the roof and the areaways, which serve to ensure better protection of the architectural heritage site. Generally speaking, one can only be amazed at the sturdiness of the construction of such buildings – a two-century old wooden building stands tall and keeps on being quite usable. And, although from the architectural standpoint, the building is quite ordinary by the standards of its days, its miraculous survival and its good preservation, of course, turn it into a unique monument of the virtually lost layer of the pre-fire Moscow architecture.