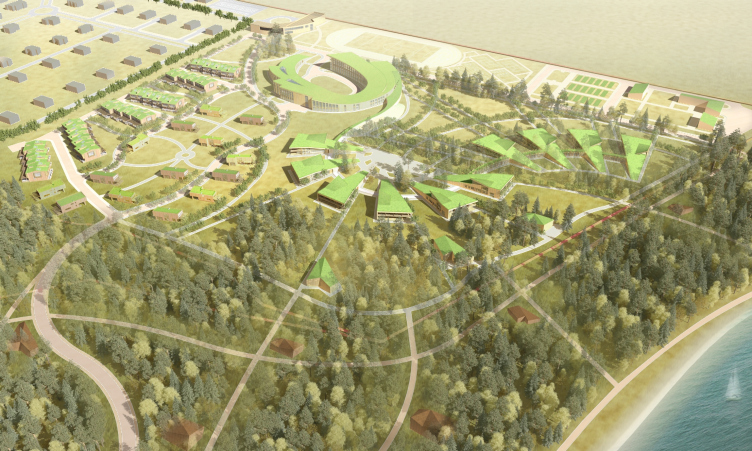

The residential complex "Zolotye Peski" ("Golden Sands") occupies an area of some 24 hectares and is located practically on the shore of the Mozhaisk Sea. It is only separated from the beach by a narrow strip of woodland and by the territory of an incomplete villa community. Actually, it was this project, only a third of which has been presently completed, that became the starting point for the whole affair. As Vladimir Bindeman reminisces, early last year he was approached by a representative of one of Moscow financial companies that bought out an incomplete villa community in Moscow area's Mozhaisk District with an intention of turning it into something more than just a trivial string of standard townhouses. The ambitions of the new investor stretched far beyond the boundaries of the housing project - the territory that one has every reason to call a resort type was going to get a unique sports and recreation center capable of accepting children alone (as in a summer camp) or whole families coming down for a vacation together. In other words, the architects had a task of, first of all, zoning the incomplete settlement, singling out the center territory, and, second of all, actually developing from scratch a recreation complex of a new type.

One must mention at this point that originally the settlement used to have a terminally rational, not to say trivial, planning grid: it was supposed that two trapezes would stretch from the road to the lake, cut through with the parallels of the inner driveways, on each of which two lines of land plots were to be strung. The townhouses were designed just as unassuming, although even in such form they were not all implemented - because of the economic crisis, most of the land plots were sold without the construction commission because the owner wanted to sell them at any rate. Still, the builders were able to fix the framework of one of the trapezes, flanking it with houses standing along its perimeter, and the architects, of course, could not ignore the already-formed residential nucleus. The obvious solution in this situation would be developing the other half of the land site in a crucially different system of coordinates. At the same time, the authors of the project did not have an opportunity to organize a dedicated driveway to the territory of the future center, and this is why it stretches away from the settlement and along the highway: along its entire length, the architects placed parking lots and maintenance buildings, marking the turn towards the complex itself by an entrance group. Embracing the roundabout in a smooth half-arch, it looks as though it were prompting: from this point on, you will see a territory of a crucially different geometry and architecture.

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea. Location plan © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

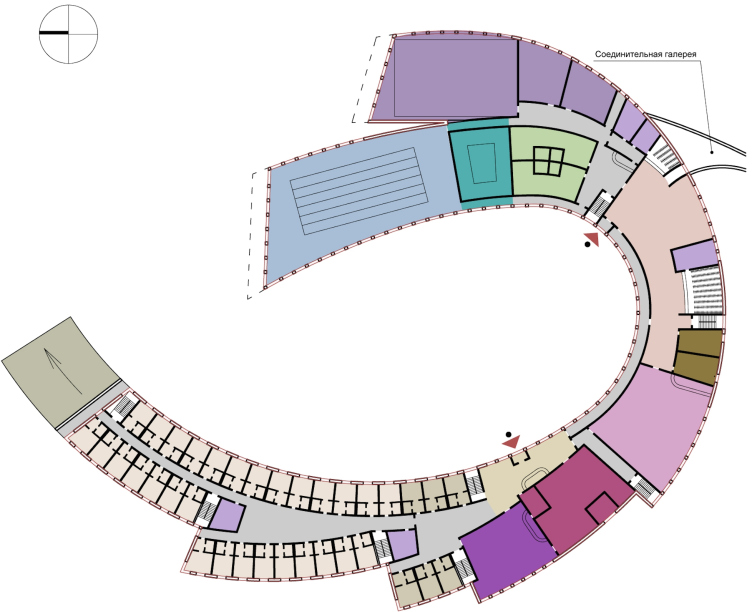

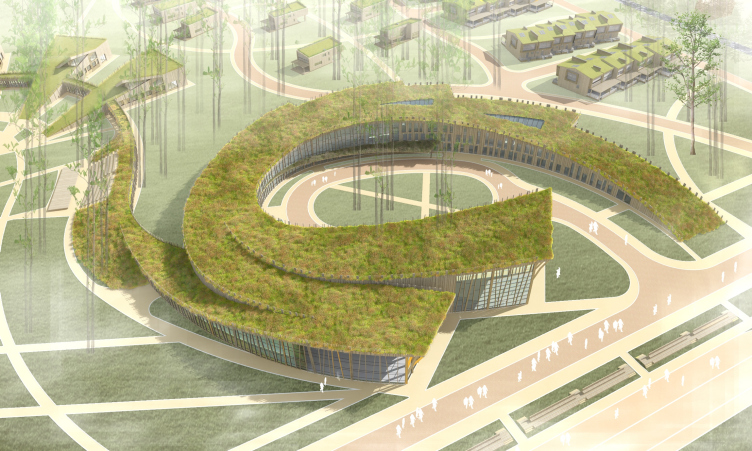

From the settlement, as well as from the highway, the complex is separated by two buffer zones: the residential area is overlooked by the stitches of the twin-houses, while the territory stretching along the highway is taken up by soccer fields, an eco-farm, and a mini-zoo. In the structure of both groups of buildings one can still trace linearity, while the plan of the center itself is ostentatiously irregular. The main building where all the public functions are concentrated (from the gyms and the swimming pool to the clubs, the conference hall, and the hotel) on the plan resembles the "G" letter, whose "tail" stroke is the head of the roofed gallery connecting the "headquarters" with the other units. This gallery then stretches, winding, along most of the land site, serving as a thread of sorts upon which the residential units are strung. As for the latter, the architects gave their plans the shape of elongated pointed triangles: some of them are oriented toward the highway, and some, on the other hand, toward the water - which makes the composition all the more dynamic.

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea. Plan © Arkhitecturium

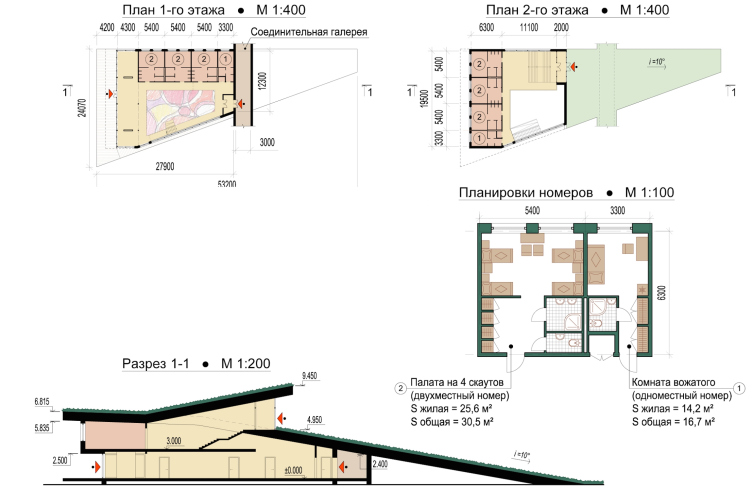

As Vladimir Bindeman shares, he decided from the very start to design the buildings of this center out of wood, and of the untreated kind, too. "The complex is located more than a hundred kilometers away from Moscow, and I thought it made sense that the people coming down here would want to find themselves in an environment drastically different from the "concrete jungle" - the architect explains - The customer agreed with that at once but he put forward the condition that we streamline as much as possible the impeding expenses and that we find the most cost-efficient solution possible". As Vladimir Bindeman explains, it was all about the most rank-and-file timber one could possibly think of: no glued wood, nothing that underwent special machinery treatment - just the uncut timber with its characteristic rough texture and cracks and crevices. "We were not even going to paint them - just cover them with bio-protection solution and leave them to age naturally, so that they would gradually fade and take on that silver gray hue".

Also important is the fact that the use of the "framework-insulant-sheeting" algorithm provides an opportunity for making the basements lighter and avoid using the lifting cranes altogether - yet another way to save a significant sum of money. Ultimately, the only thing that the architects were not going to cut the costs on was the high-quality stained-glass - the large amount of glazing in combination with the ostentatiously rugged surfaces of the wooden façades and their expressive geometry is something that primarily forms the image of the complex. It is augmented by the green, fully usable, roofs - actually, the roof of each unit is "pulled down to the ground" on one side, which turns the building into a gently sloping hill inviting to walks and outdoor games.

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea. Bird's eye view © Arkhitecturium

The green roofs also play an important metaphorical part - they serve as that "visible connection to nature" that became the central part of the whole project. Out of these same reasons, by the way, the architects discarded the idea of organizing the territory of the complex in a standard way: instead of paving the trails with paving stones or using asphalt, they came up with a system of planked footbridges, through which grass is shooting up, gravel envelopes, and curbs made of logs. The roof of the administrative building is also green: at the expense of the varying number of floors, the architects were also able to execute it in the shape of a gently sloping hill, some kind of a green ramp that one can ascend directly from the entrance gate and then walk upon, thus crossing the entire complex from end to end. This exciting journey, by the way, is but one of the numerous activities that the architects came up with for the young guests of the sports center. Also, it was planned to create here a children's yacht club, a rope park, a swimming center, the already-mentioned eco-farm and the mini-zoo where children themselves could take care of the animals. And, although this project is still in the concept stage as yet, its "green" part got high critical acclaim from the experts: at last year's Zodchestvo festival, it was awarded the honorary award for its architecture of humane environment in "Sustainable Architecture" nomination.

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea © Arkhitecturium

Sports and Recreation Center at the Mozhaisk Sea. Plans and section drawings © Arkhitecturium