We have already covered the project of "Literator" residential complex in Moscow's district of Khamovniki: "Sergey Kiselev and Partners" designed it on commission by "Gals Development" in the stead of a former brewery at the crossing of Rossolimo and Leo Tolstoy streets. The land site is rather large by Moscow standards - around two hectares - but is sunken into the yards and surrounded with protected buildings practically from all sides: one building of the brewery, the oldest one, low-rise, the one with a chimney, separates the complex of the park that belongs to Leo Tolstoy museum; another - a three-story building of the late XIX century, stretches along the street that bears the great writer's name; the third one - the Institute of Drinks built in the late seventies and now looking rather on the shabby side forms the line of the Rossolimo Street. The appearance, against this motley backdrop, of a new elite residential complex is almost unfelt: on the red line, it only manifests itself by two small buildings neatly inscribe into the breaks in the city matter.

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Master plan © "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street © "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. View of the yard from the direction of the brewery. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

According to the chief architect of the project Aleksey Medvedev, the authors' two main tasks were: to squeeze as much as possible of usable floor space within the existing limits - and here, in the proximity of Leo Tolstoy estate, these limits are rather strict - and to "avoid vulgarity" that was suggested by the elite central location and, again, the proximity of the museum. And, indeed, the architecture of the project is all about austere geometry and is reserved when it comes to details. Meanwhile, at the developer's website, the "modern classic" term is used anyway. But then again, one could also agree with this definition for a number of reasons: although completely devoid of so much as a hint at historical decor, this complex is in fact part of the red-brick tradition that came to Moscow from Berlin and over the last ten-fifteen years has become the recognized standard of filling in the spaces in the historical districts. Such buildings, as a rule, combine the plaster coating - a favorite with the city architecture of the 2000's - with different types of unusual bricks, the peculiar thing being that while the Jurassic stone can merely function as backdrop material, it is the brick that actually defines the identity of the building, sometimes black, sometimes gray, sometimes rugged, sometimes textured. In "Literator" buildings, this is precisely the case: the architects deliberately chose not the brown brick (the kind that Moscow got tired of as early as in the late 2000's) but the saturated red. The resulting color is still a little on the brown side but it is picturesque enough to fit in with the street's color palette formed by the factory buildings of the late XIX century.

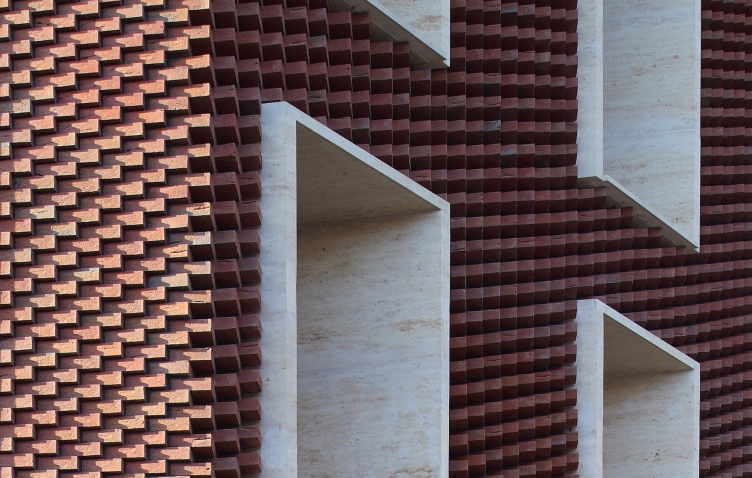

Furthermore, the most curious themes of "Literator" architecture are built specifically on variations of red-brick coating. The brick is rugged, the introductions of sand and clay are clearly traceable; the brickwork is evenly diluted by "burned-out" violet fractions that are meant, just as everything else mentioned above, to give the wall a handmade look, akin to historical. The architects, however, do not limit themselves to the basic rank-and-file set of techniques here.

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Because of the fact that the complex is inscribed - or, as the architects say, literally "squeezed" into the yards - it is completely devoid of the traditional main pride of any such establishment: the grand facade. Try as you might, there is just no place for it. But, since one of the goals was staying within the limits of the "image of today", instead of the proud representational composition, the complex exits to the street with a few driveways and two quite small buildings. One of them, turned to "Stroganoff" office center, is minimalist and simple: it is only livened up by the inserts of whitish bricks that look like flecks of sunlight (their surface is sandblasted with some light substance). The strokes of the light-colored bricks reminding one of the spring sun are to be seen on the inside buildings as well.

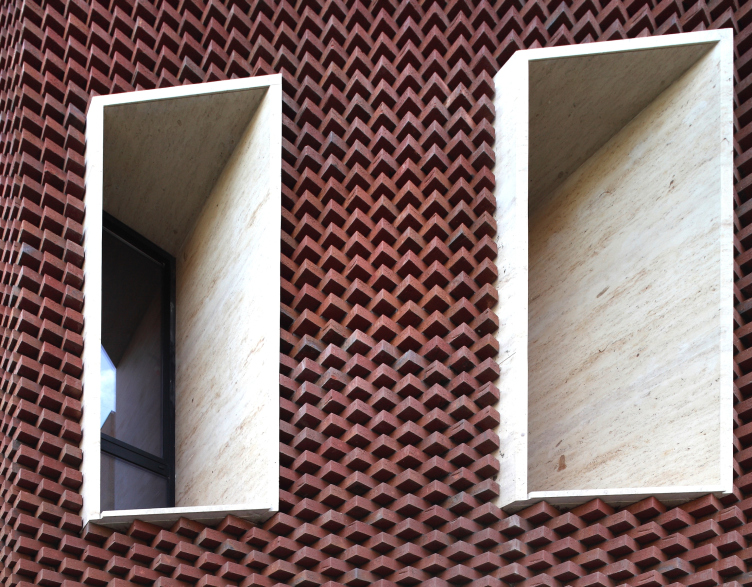

Another building that exits out to the street is the corner Building A; it takes on the role of the main accent because it is the most curious of all. The building overlooks the crossing of Leo Tolstoy and Rossolimo streets, spacious and almost undecorated, and the new building sensitively reacts to its urban incompleteness. Its corner facade turns along a parabola but its shape is not exactly rounded but faceted, and, what's more, the bricks do not change their direction in accordance with the wall surfaces: they line up as a "saw", showing their jagged edges first tentatively then at full force clearly stating that they are not at all the facing sommer and not even rock-bar but the noble plinthiform bricks. Which, of course, is an illusion: for the textured part, special brick is used, and in all the other places it is sommer.

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. The non-residential building at the corner of Leo Tolstoy and Rosolimo streets. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Corner building. Fragment. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Corner building. Fragment. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Anyway, in the places where the walls are slanted, the brick does not trace their surface but bristles in saw teeth. This is the way some columns might look in a derelict manor estate - but in the case of this derelict major estate they are truly in a neglected state while here it is meant to look this way. In fact, in the corner building, the architects did something that can be called deconstruction of the facade: they left the facade deliberately unfinished as if it - like many Italian temples, Saint Lorenzo in Florence, for example - never got its facing work. The theme is picked up by the slim boxes of the white stone window frames inserted in the rough thickness of the brick - as if waiting to be decorated. But alas - it is destined to remain skinless forever.

These bristling bricks - the ultimate antithesis to the grand facade - practically become the manifesto of "Literator" architecture. This "sign facade" is executed with a fair share of incompleteness, not devoid of artistry. On the southern side wall of Building B, turned to the playground and the old building of the brewery, the theme of incompleteness continues: here the wall is designed as a softly drawn indenting of the brickwork. This texture appears at a few more side walls signifying the internal "breaks" between the buildings; the stripes rhyme with the spots of the brick grilles - this is also an environment element borrowed from the neighboring Eyesight Research Institute (the fence may be taken down in the future but the reflected motif will remain).

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Fragment with the brickwork grid. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. facade with indented strips. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

This incompleteness of the joints turned outward looks like a declarative gesture having to do with considering the place of this complex within this city: its being at once skin and alien to the territory that it occupies. The buildings look like "wanderers" - as if they had been severed from somewhere, then brought in here, and the jagged edges of the breaks remained. The message is encoded, though: if, while passing by, one simply glances along the building he can enjoy the play of light and shade on the unusual brick texture.

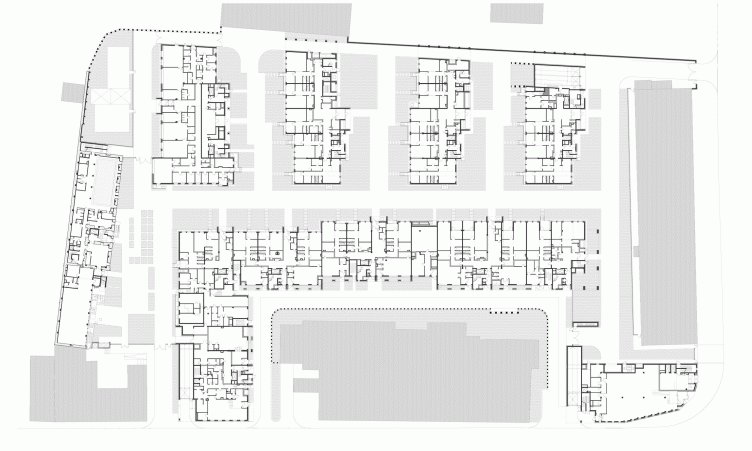

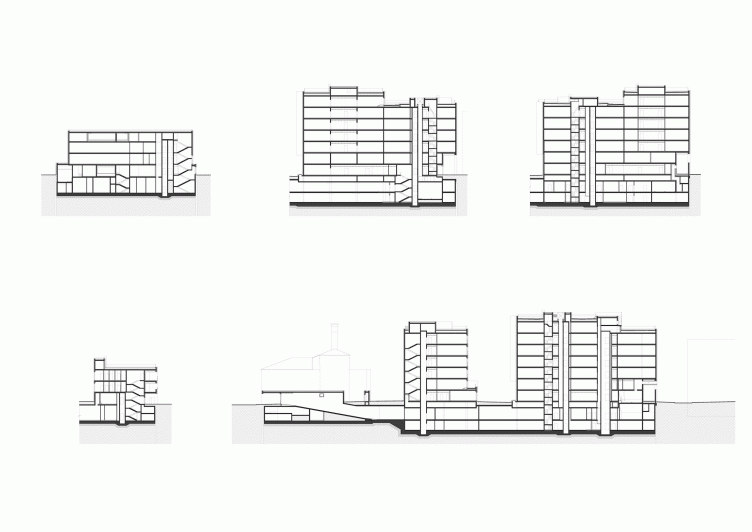

But still the complex is an elite housing establishment - it has penthouses with terraces on their roof, and two-level apartments. The subtleties of the contextual meanings are not the most important thing for it, and on the inside, where the city's restrictions are less strong, the buildings grow considerably larger, taller, and more respectable-looking. The white stone and the red-brick volumes alternate and grow into one another forming sometimes projections, sometimes indents, livening up in groups of deep stanzas and arrays of transparent balconies. The beam of the long Building "B" stretches along the red line of an inside street parallel to Leo Tolstoy. Livened up by asymmetric projections, its facade is clearly visible in the breaks in the building front, and it also plays the "representation" part - in its own way, even if from the back row. The long house works as a fence that protects the space of the inner yards with three short buildings whose first floors are slit with an enfilade of tall driveways on long "legs" clearly viewable from the Rossolimo street. The architects say that it might have been easier to simply set another long building inside the yard but they took a different path, fracturing the yards and stringing not a material but a "territorial" axis through them. There is getting inside: the security guards are watching over the peace of the future inhabitants of the elite complex, it is only the street running along Building B that is accessible to the general public.

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. facade of the "beam" building. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

The architecture inside the complex is also not devoid of a note of deconstruction that livens up the masses of bricks and stones. First of all, the windows in the brick walls are framed by slender white stone frames that do anything but try to merge with the wall surface - instead, they look like stone slab "boxes" inserted into the wall mass with similar slabs of windowsills. Second of all, the brick masses are sometimes streaked with broad stone bands, and sometimes with relief lines of slender grid that turns, when it reaches the bottom floor, into a large-cell grid filled with bricks, provoking a play of associations - it all looks as if the shop windows or even the Corbusier "legs" of the house were stuffed with bricks now. In a word, the stone-and-brick stylistic of recent years blends in this complex with earlier, though not completely exhausted yet, modernist deconstruction variations of the nineties, strokes that go a long way to lighten up the hefty stone volumes.

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

The architects of "Sergey Kiselev and Partners" also came up with the design of the entrance lobbies - initially laconic, from wood and stone, but later on, at the customer's request, the architects added a "literary" twist to it, although also to rather a moderate degree. The reception desk is decorated with italic characters, the walls are made of the same stone as the facades, and are covered with picturesquely scattered niches with wooden frames, the filling of which - flowers, photographs, and whatnot - is left to the discretion of the people who will live here. The darkish color of the wood echoes the window frames in the entire building while the leather of the armchairs enhances the "literature" quality, reminding of the furniture of Leo Tolstoy estate nearby.

Interiors of the public and residential zones of "Literator" complex © "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

However, the exquisite laconism of the cultural codes seemed to the customer to be not dramatic enough - and the architects painted a picture on the wall of the institute building turned into the yard of the complex, a picture bearing a spiritually patriotic message, showing a Russ guy in straw shoes and with a wolf by his side. Some of the future inhabitants of the complex, just as the architects, sincerely hope that later on thus masterpiece will be taken away.

Back to the architecture of the complex, though! It turned out to be both laconic and up-to-date, and contextual as well. The district of Khamovniki is a place that is elite but historically discreet; it never did form the homogeneous city fabric, just like most of Moscow which, as everyone knows, is a "big village". This place used to have in it manor estates, wooden houses, and brick factory buildings later on. There is even one chamber remaining from the "Khamovniki Yard" of the XVII century; now it is surrounded by a park with American maple, imitation historical houses, and a couple of diagonally standing Brezhnev high-rises. The buildings of "Literator" neatly grow into its queasy surroundings strengthening their character towards the nucleus of the complex and "dissolving" at the edges. Besides, quite nearby, on the opposite side of the Leo Tolstoy Street, "Krasnaya Rosa" ("Red Rose") factory stands renovated into an office center also by the architects, though different ones, of "Sergey Kiselev and Partners": the facades of "Literator", although not quite perceptibly, but still echo the asymmetry of "Morozov" office building, forming, in addition to the contextual discourse, the ties that could be classified as the blood type - between different projects done by the same studio. Yes, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners" have built enough in Moscow to self-react to their own works as well.

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Corner building. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Photograph © Mikhail Serebryakov, "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Plan of the first floor © "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

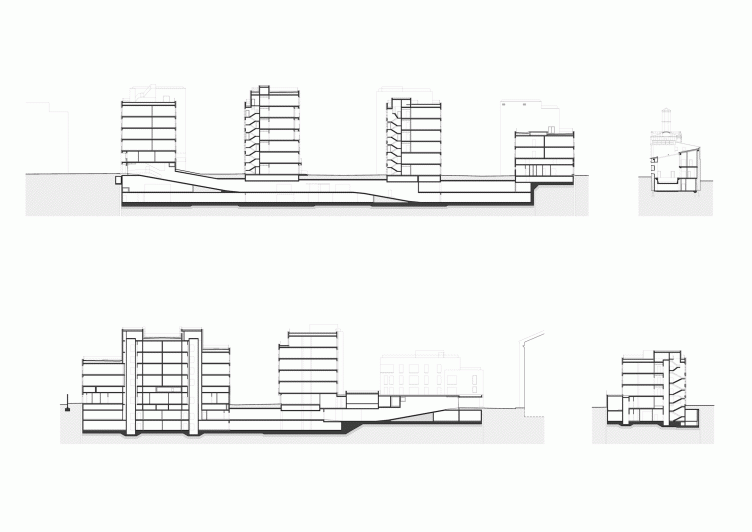

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Section views © "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"

Residetial complex at the Leo Tolstoy Street. Section views © "Sergey Kiselev and Partners"