Two parts of the complex, separated by the ex-xemetery, and the towers of the business center over the Gorky Highway. Project. Image courtesy of "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

In 2008, 'Ostozhenka' Bureau was approached by the young and dynamic

company 'Tekta' that proposed to design a large-scale residential complex in

the center of Balashikha. At that particular moment, the commissioner's

portfolio only included one complete project in the city of

Speaking of the experiments - the very construction site lent itself to

them. The site is situated in the heart of Balashikha, between two highways -

Gorky Highway M7 traversing the city from east to west and its duplicate - the

city's "Main Street" named "Lenin Avenue". All the surroundings

literally revel in verdure, the western border of the site being marked by the

still-intact cascade of man-made lakes stretching along the

In the early 2000's, the city council even organized an international

tender for the building of the "Center" - this is how this area is

referred to in Balashikha. Teams from

Being very much in the know of Balashikha's town-planning issues, the

'Ostozhenka' architects took the commissioner's proposal as a chance to make a

positive difference in the life of the entire city. This is why, concurrently

with designing the new residential complex, they developed a project of two

high-capacity flyovers on the

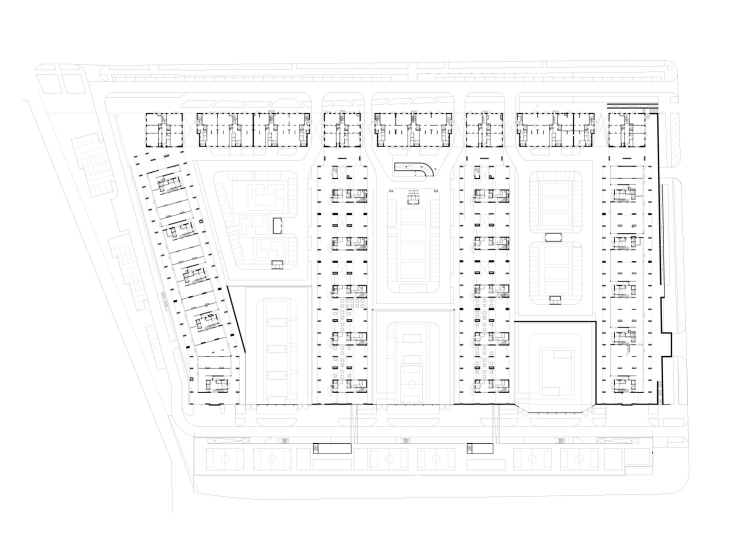

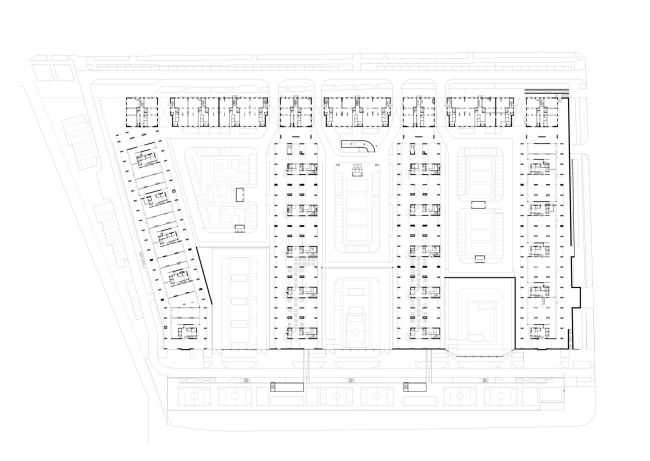

Plan of the ground floor. Photo courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

As for the "Center", being practically devoid of all of its

functions, it became the construction site for a housing project. And what a

project it is! Diluted with splashes of colors, the complex got a poetic name

of "Akvareli" ("Watercolors"). It looks like a watercolor

painting indeed that, while keeping the fragments of the white sheet, fills its

space with colors with a multitude of reflections, which is enhanced by the

abundance of water around the complex... The river, the lakes... But first

things first!

Presently, in construction is the block named 'East', while the block

named 'West' (so the authors call the constituent parts of the complex) is

still in the concept phase (we will give it a more detailed coverage in our

next issues). The two equal-sized blocks are separated by a green stripe of the

park. As the chief architect of the project Rais Baishev shared, this is not just

any park. Once there was the graveyard of the ancient settlement, then there

was a cemetery. From the middle of the last century it has been closed; now it

is overgrown with tall trees and has a status of a memorial park. It is still

hard to say if the dwellers of the future complex will be OK with this

vicinity. "In

The idea to fill the site up with a forest of high-rise towers was

dismissed at once - the architects tried to make the buildings as low rise as

it was possible in this situation. Keeping up the necessary number of square

meters was only possible due to the use a mixed typology: they crossed the

tower, sectional, and gallery types of housing. This is not its only

peculiarity, however: the residential complex became a veritable collection of

the architects' favorite techniques, if not to say - archetypes of classic

modernism.

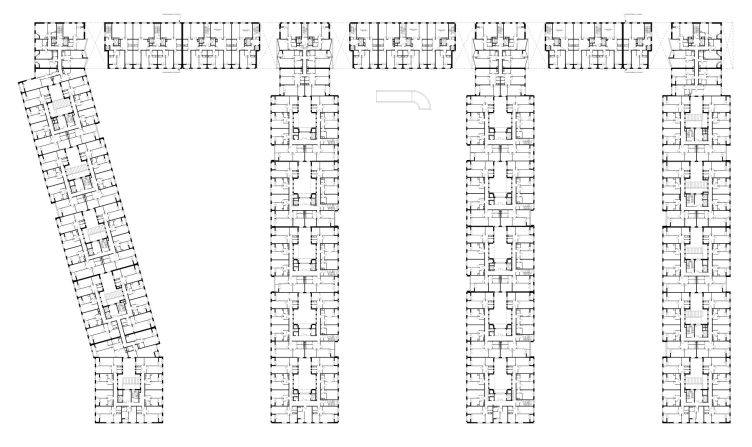

Its plan looks very much like a hair comb with four long raked teeth.

The teeth reach out in the direction of the highway, while their

"base", the handle of the imaginary comb, is stretched along the

boulevard and is in fact a 14-story house some 300 meters long. It might be a

"wall house" or even a "beam house". If one looks from the

highway side or, better, yet, from the bird's height view, it becomes evident

that the four transverse buildings are supporting a long beam, and the whole

thing becomes a "horizontal skyscraper". However, the space above the

beam is filled with residential quarters (it would have been a shame to lose so

much of the square footage), and, when viewed from the boulevard side, it looks

indeed like a "wall house", the closest kin of the famous building at

Tulskaya metro station. The house is pierced with three driving openings,

though, that let the sun rays into the shady side, and provide access to the

three large courtyards of the complex. Because of the 9-story height, these

openings look more like narrow slits, while the whole house, when viewed from a

distance, looks like a centipede elephant making its way along the boulevard -

drawn, though in a simplified manner, but still with a good likeness. Thus, the

gigantism of the complex is the more evident from the side of the city blocks.

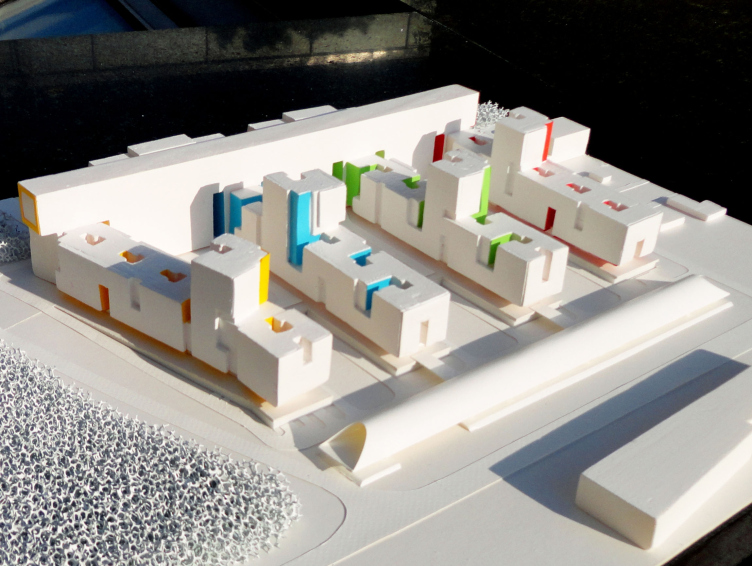

Maquette. Photo courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

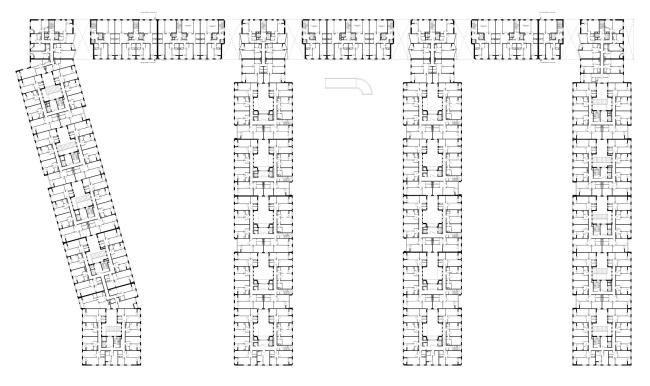

The four 9-story buildings (the teeth of the "comb"), turned

in the direction of the highway, and, in the farther perspective, to the

Golitsino Manor, were made as low-rise as possible. The logic way to reduce the

height without losing the square meters would be increasing the breadth, which

resulted in each building being 30 meters thick which is twice as much as the

average residential building. Because of that, the architects turned these

buildings into sequences of rectangular (almost square) sections, each one with

a courtyard of its very own. Inside, the courtyards are overlooked by the

corridors that connect the apartments and it turns out that each block is in

fact a gallery house that, like a snail, coils around its "light"

center. One of the blocks of each building grows from nine to seventeen floors,

and thus the four towers appear.

Plan of the zero floor. Image courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

Further on, the modernist classic in its pure form begins. All the four

buildings, just as was bequeathed by Le Corbusier, are put upon supporting

pillars. The ground floors are non-residential and the transmissibility of the

pedestrian area is violated in but a few spots by a few shops and cafes, set up

in between the concrete "legs" of the two outer buildings and marking

the border of the territory in a punctured line; also - by the inevitable

blocks of stairwells, elevators, and lobbies with transparent glass walls. In

different versions of the project, the legs look different: sometimes they are

thin and have a square section, sometimes they are flat and trapeze-shaped,

like the "Unité d'Habitation" or

"Watercolor" residential complex. Photo by Aleksey Lerer, April 14, 2013, in the process of construction. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

View fromn the water area. Project. Photo courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

"Watercolor" residential complex. Photo by Aleksey Lerer, April 14, 2013, in the process of construction. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

As if answering the transmissibility of the lower tier, the upper parts of the buildings also get a lot of slits. First of all, this refers to the sections with the inner courtyards - the slits allow for letting more light inside. For the 17-floor towers, whose yards are true "wells", the deep slits are all but mandatory: over the fifth floor their pan is no longer square but П-shaped.

The slits are echoed by large niches: here and there the architects cut

out of the wall a fragment some five floors high and about a meter deep.

When they do this, it turns out that, in spite of the fact that the skin

of the buildings is dazzling white (from fiber-cement panels), they are colored

on the inside. This is like cutting open a watermelon and finding the red pulp

inside the green peel. Everything that is on the outside is achromatic-white

but once we get inside - no matter in which manner, by going through the lobby

or simply observing the cutaway on the facade that the architects made in the

prismatic volume - it turns out that the house is color, very much so. Each

building has a color of its own: red, blue, green, and yellow - we see it in

the recessions, in the yards, in the hallways, on the surfaces of the walls and

on the ceilings of the permeable first tier. In a few versions of the project,

this same color appears on the lower surface of the protruding marquees.

Yard territory. Project. Image courtsey by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

"Watercolor" residential complex. Photo by Aleksey Lerer, April 14, 2013, in the process of construction. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

"Watercolor" residential complex. Photo by Aleksey Lerer, April 14, 2013, in the process of construction. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

"Watercolor" residential complex. Photo by Aleksey Lerer, April 14, 2013, in the process of construction. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

The color that is used is bright and simple; the shades appear thanks to

the reflections of the colors on the dazzling white surfaces of the wall (they

will look particularly bright in the sunny days). It is at this point that the

"watercolor" takes full effect: the color is dissolved in the

whiteness of the walls in very much the same way that the water-diluted color

falls on the white sheet of paper that "shines through". This effect

also looks a lot like a "wash drawing" - when the brush touches the wet

paper, the color immediately spreads out and makes colorful stains very much of

the kind that will appear on the walls of this building during the sunny days.

This technique, as is easy to guess, was again invented by the

already-mentioned Le Corbusier, who, inspired by Mondrian, painted the slants

of the recessed balconies of the "Unités d'Habitation" into the

bright basic colors and eventually got a more sophisticated perception of the

basic colors when viewed not directly but in perspective.

This motif, that is simultaneously simple and

sophisticated, has become one of the favorites in the contemporary

infrastructure: the colored partitions and color reflexes are very popular,

suffice it to recall the Japanese experiments of the French EMMANUELLE MOREAU.

The "Ostozhenka" version is more large-scale, and it is not devoid of

some extra meaning: color will become the characteristic mark of each hallway -

while passing through the yards one will not have a chance of making a mistake,

so strong will be the immersion into the color that is going to shine from up

above and get reflected in the pavement.

"Watercolor" residential complex. Photo by Aleksey Lerer, April 14, 2013, in the process of construction. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

"Watercolor" residential complex. Photo by Aleksey Lerer, April 14, 2013, in the process of construction. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

As we can see, the giant housing complex in Balashikha

uses the best traditions of modernism. What is interesting, however, is the

fact that these traditions in this particular case are not formally present

("look, we're paying homage to avant-garde here") but are fully used

to organize the urban space and give new meaning to it, proving spectacular and

relevant. In this sense, "Watercolor" district is the living and

righteous heir of the pilot districts of the 1970's, from which in this country

only one, namely Chertanovo, was built; in the European countries such blocks

are pretty wide-spread (see, for example, the Archi.ru feature on

However, it is easy to see that "Watercolor"

is not identical to the neighborhoods of classical modernism. They would have

hardly been so respectful of the context or would have tried to reduce the

number of floors because of the neighboring manor house; the sequences of the

courtyards would hardly have been possible either - this motif refers us to the

tenement houses of Saint Petersburg or, to be more exact, Italian palazzos with

galleries built around the courtyards; modernists, on their part, preferred

"slab" houses. Towers were not much favored in the 1970's, either. This

is why in the Balashikha house we see rather an alloy of the classic modernist

techniques and later, more subtle, solutions justified by the context,

insolation, and other conditions. But then again, nobody thought that

'Ostozhenka' would settle for less.

Yard vies between Buildings 2 and 3. Photo by A.Gnezdilov, October 2012. Courtesy by "Ostozhenka" Bureau.

Courtyard view in the summer of 2013; the facade of the "long" building with diagonal recessed balconies is almost complete. Photo from the "construction diary" from the residential complex website www.wcolour.ru