First things first, however. The exhibition has several peculiarities: first, it is a research-based exhibition, and in our time when most people focus on entertaining the venerable public for money, and the prefix “scientific research institute” is often hastily dropped as something embarrassing, the museum fully justifies its prefix. I can’t say it happened suddenly – I’ve been observing the museum for over 20 years. I saw it go through all stages from denial to acceptance, being a very dull scientific institute, then a trendy hangout with vodka and pickles in the icy Ruin – yes, the place has been through a lot of things. Throughout this time, however, it nevertheless faithfully served as an architectural archive for researchers. Here, a compliment is due to Elizaveta Likhacheva: under Irina Korobina’s leadership, they restored the Ruin and opened a temporary version of a permanent exhibition. However, it was under Likhacheva that significant museum exhibitions once again became fundamental, one after another, with originals, research, and hot exhibition design.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

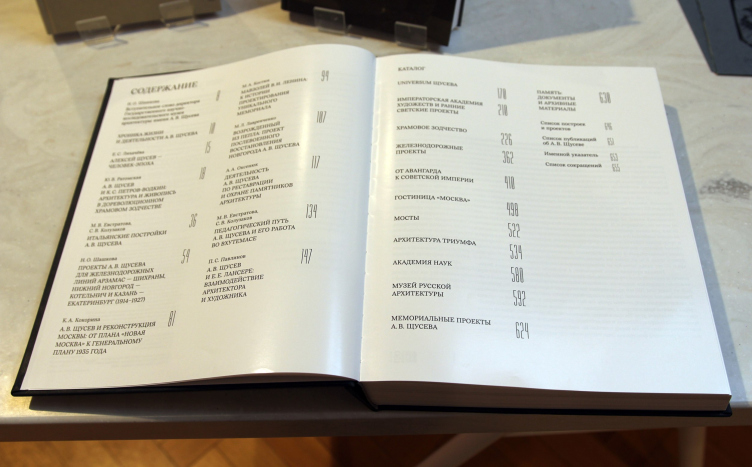

Moving on! When they began preparing the exhibition about the “founding father”, it turned out that everyone seemed to know “everything and at the same time nothing”, as Alice in Wonderland would say. There are yawning gaps in the books, not everything has been published, and a comprehensive monograph is still nonexistent. There is one about his church projects written by Diana Keypen-Vardits, and probably, in time, another one will appear, more thorough, based on Aleksey Shchusev’s personal archive – this time written by Sergey Koluzakov. But, in general, Aleksey Shchusev’s legacy has not been fundamentally studied. The exhibition is by no means a monograph, but it fills some gaps, especially since its catalog, 7 centimeters thick and weighing as much as a full-size brick, is combined with a collection of 9 research articles on various topics. Honestly, I’m clueless why they did it this way – it would have been much better to publish the collection separately, and it would have been easier to buy it. Nevertheless, it provides a solid foundation for further study of Shchusev’s architecture and biography.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia tarabarina, Archi.ru

Equally valuable is the two-volume set: one volume contains the memoirs of four individuals, and the other contains all of Shchusev’s articles and written works. Additionally, the museum regularly posts small fragments about Shchusev on its Telegram channel, which is also intriguing and well-suited for those with a clip-like consciousness. Plus, there’s a film, or actually even two: one produced by the museum and another by Russia’s First Channel.

This is certainly not a monograph, not a definitive and thoroughly researched study, but rather a preparation for it – a curious sign of the times when information can be obtained in various ways. From all sides, we are now being told who Shchusev is.

Shchusev

I have a confession to make here: Shchusev is not very clear to me as an architect.

For some, he is the architect of Marfo-Mariinsky Convent with Konenkov’s carvings and Nesterov’s paintings, for others, he is the author of Lenin’s Mausoleum, and for others, he is just an obscure name in the museum’s title. He was a very versatile architect, seemingly the only one who not only navigated but also succeeded, with good results, through the twists and turns of the first half of the Russian 20th century.

Shchusev′s posthumous portrait, which stood in the corner on the stairs, was moved, now it is in front of the entrance to the Enfilade. Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Such a “versatility” in the 20th century, which can boast lists of modernists who did not embrace classicism and classicists who did not embrace the avant-garde, is somewhat challenging to understand. For some reason, he could do things that no other architects could afford to do. According to reports, he criticized VKHUTEMAS and its graduates for illiteracy, yet he worked in constructivism, modernism, various forms of Stalinist classicism, and elaborate national styles. A vivid example is the theater in Tashkent, which occupies half of the exhibition hall. After the Second World War, he undertook projects for the reconstruction of cities: Stalingrad, Istra, Veliky Novgorod, Tuapse, and Kishinev. In other words, he was both a temple and a city builder.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

One probably cannot categorize Shchusev as a restorer, yet with the participation of Peter Pokryshkin, he reconstructed the pre-Mongol church of Vasily in Ovruch for Nicholas II, placing the found fragments back in their “original” places. He also took a serious interest in the history of architecture. The key monument of the Soviet twenties – the Mausoleum, or more precisely, Lenin’s Mausoleums – likely became a kind of protective decree for Shchusev. Whether as the author of the communist leader’s tomb or simply as a very skillful person, he almost without losses survived not only shifts in stylistic preferences but also Stalin’s repressions.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Alexey Shchusev also defended the exiled restorer, Peter Baranovsky. What’s even more surprising is that when he was “denounced” in the Soviet newspaper “Pravda” by his architect colleagues, the kind individuals Saveliev and Stapran in 1937, Shchusev was merely demoted and not expelled from the Union of Architects after this article. Other architects were exiled or even executed after such accusations. How was this possible?

All of this can be explained and understood in different ways. The word “versatility” obviously had negative connotations back then – either you’re for the Reds or the Whites. However, you can also look at it differently, as one of the four curators, Anatoly Oksenyuk, the museum’s deputy director for science, said at the exhibition’s opening: “A person who wants and can work will work and will be successful”. I must say, it doesn’t always work out, but what a beautiful motivational message for everyone!

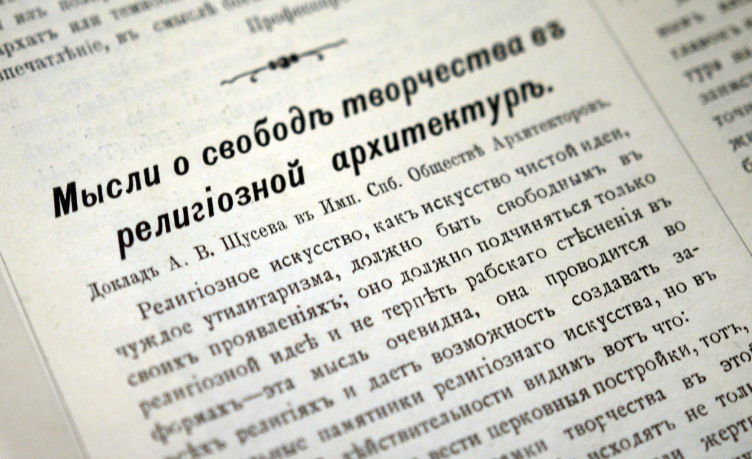

And somehow, I can’t help but think that there are people who should, perhaps, have lived forever. If Shchusev lived in our time, he would probably have excelled in high positions, building towers, stadiums, and leading master plans. I don’t know if he could have made post-Soviet architecture happy; that seems unlikely. However, he would have undoubtedly made it efficient. Maybe I’m wrong – look at the words of the young Shchusev about church architecture. It’s as if those words should be carved in stone: “It should only be subservient to the religious idea and not tolerate servile constraints in forms”.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina / Archi.ru

In short, there’s a lot to take in.

It’s not surprising that one of the exhibition’s tasks is to showcase the diversity of Shchusev’s personality while somehow encapsulating or “pulling it together”. The architectural design of the exhibition by Sergey Tchoban and Alexandra Sheiner significantly aids in achieving this goal.

The Exposition

The exhibition’s design is the second distinctive feature here. It is light, simple, and concise. With this design, the exhibition resembles a fashionable magazine – well-designed, with unobtrusive comments. Particularly noteworthy is the placement of the museum’s new logo in the middle hall, shaped like the Cyrillic letter “Щ” and resembling Latin numbers of Mausoleums. It feels like we are walking inside a book about Shchusev, a book that, I must remind you, is not yet complete. Not literally, of course; it’s a metaphor, but the sensation is intriguing.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Another feature of the exhibition design is its tactful approach to historical interiors, both the classical Enfilade and the vaulted “Aptekarsky Prikaz”. Unlike other exhibitions that fence off or compete with historical spaces, this one, simple and white, goes down quite well. Alexandra Sheiner told me that this was intentional: in some cases, the exhibition designers even reduced the height of the stands to make the medallions behind them visible, suggesting illuminating the medallions. These are sensible decisions not only because historical settings should be respected (admittedly, this doesn’t always work), but also because the halls of the Enfilade themselves are, in a sense, exhibits – they were where Shchusev’s museum opened back in 1948.

The most obvious statement about the architect’s diversity is placed upfront in the first hall: here, headlines like “museum worker”, “defender”, and “restorer” greet us. Interestingly, the main title, “architect”, is missing, likely implying, “who else but an architect”. Also, there’s a list of major state awards, from imperial to Stalinist (Shchusev did not outlive Stalin; he passed away in 1949), and a portrait, an oil painting in a gilded frame. I must mention that a few such “standout” elements, deviating from the overall flow, are connected to the fact that storage sources required not altering the works too much, so the frames were somewhat obligatory, but they also contribute to the exhibition’s diversity.

The rest, and, as we remember, there is a lot of material, is neatly and meticulously integrated into the concept: white frames rhythmically complement and partly neutralize the inevitable variety in graphic formats. Most of the halls are immersed in white, enlivened by a simple stepped form whose source, as the authors explain, is the silhouette of the Mausoleum. Moreover, Sergey Tchoban and Alexandra Sheiner found the proportions of the Golden Section there, near Lenin, and constructed their steps also in the “golden” proportion: slightly more, slightly less.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Inverted pyramid shapes form supports for models, and only in one place – in the small pass-through hall dedicated to bridges – did the architects allow themselves to construct large steps, adding a perspective effect to them: the middle part is slanted, which, in the overall restrained design, produces the desired effect, especially when walking back towards the exit after viewing the exhibition.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Equally impressive is the arc-shaped bench in the center, like some “swing” if you imagine it depicted on a master plan, somewhere between the avant-garde and imperial classicism. There are also white schematic plans of cities in the design of the reconstruction projects that Shchusev participated in after the war: Stalingrad, Istra, Veliky Novgorod, Tuapse, Kishinev. Metal racks in the final hall of the Enfilade, dedicated to the history of the museum’s creation, also make a considerable impression.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

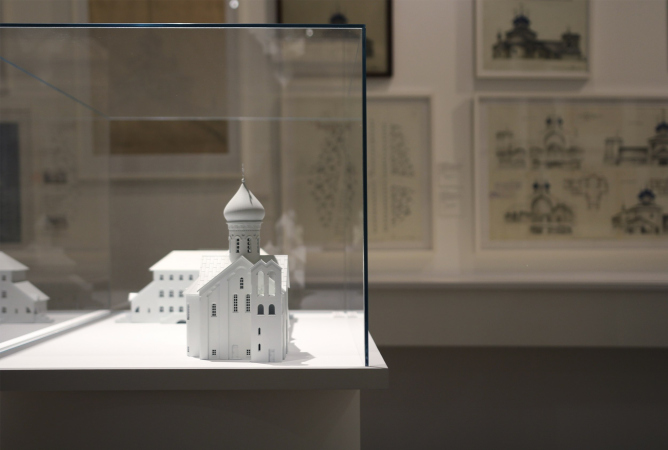

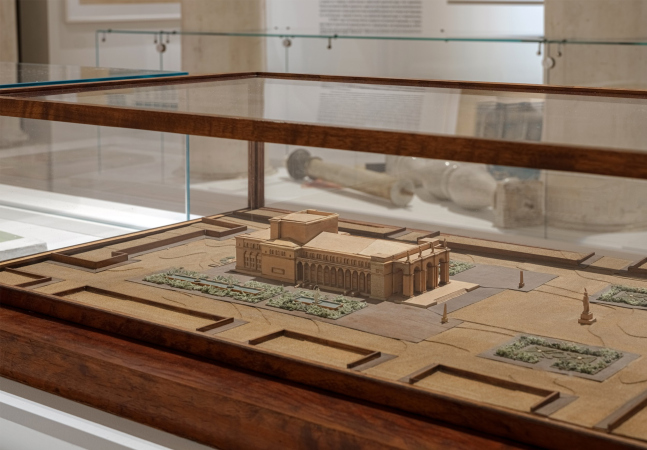

In the “Aptekarsky Prikaz” section of the exhibition, dedicated to churches, there are many more shelves, but the exhibits are placed more densely, and there are more of them. Circular and rounded column-like supports, resembling columns of Novgorod and Pskov churches, organize the space. On these supports, six white models were specifically commissioned for the exhibition. Therefore, they are of the same scale and serve as both exhibits and exhibition design elements. Interestingly, part of the exhibition infrastructure is planned to be preserved and used subsequently, including the supports and the lattice stands – simple and seemingly very sturdy despite their transparency. The “Aptekarsky Prikaz” space benefits the most, as a new wardrobe and storage rooms have been added, designed in a way that now, for any incoming visitor, it is clear where the exhibition begins—the walls “lead” the visitor forward.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Sergey Tchoban and Alexandra Sheiner allowed themselves only one colorful accent – the red hall at the “crossroads”. It reminds me of the conference hall of the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, which makes perfect sense since academic drawings and Shchusev’s diploma work are displayed in it. There’s a bit of lyricism in this decision: both Tchoban and Sheiner studied at the Academy, and defended their theses in the same hall as Shchusev.

In short, white color with a consistent theme and not too garish accents is an almost sure-fire solution for an exhibition rich in exhibits: it unites, it “smooths things out” and even makes those delicate “plastique” comments that the authors of the exhibition space allow themselves seem more noticeable. Could it be that the restrained design is a response to the criticism of the too vibrant Melnikov exhibition, according to some appreciators? Maybe yes, maybe no. In any case, the exhibition is now bright and at the same time calm, which is good because there is a lot to take in.

Multifaceted:

So, Shchusev was the builder of the Mausoleum (that’s represented in the center of the Enfilade), and Shchusev was the author of modern churches (that’s in the “Aptekarsky Prikaz”) – obvious things. But there are quite a few non-obvious “discoveries” – for those who are not very familiar with Shchusev’s work, and that’s the majority, everyone (including myself) knows him somewhat selectively.

For example, it’s important to know that Shchusev is not just the author of Kazansky Railway Station; he worked on it throughout his life, from the imperial era to the 1940s. Perhaps his career in the early Bolshevik era unfolded in such a peculiar way because he was crucial as the architect of a very large railway station – and train transportation was crucial in the 1920s, much more so for the “young Soviet republic”.

And how fortunate it is that the current museum director, Natalia Shashkova, defended her doctoral thesis precisely on the Moscow-Kursk Railway, the chief architect of which was Shchusev. This resulted in a whole hall at the exhibition: not just about Kazansky Station but also about small stations, additional ones, also designed by Shchusev. And there’s a hall dedicated to his bridges too.

Shchusev’s work on the projects of the Moscow Academy of Sciences, later built according to Yuri Platonov’s design, is also not very well-known. Nevertheless, it inspired part of the academic development of Lenin Avenue and served as the basis in some places.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

The “Moscow” hotel is also a separate story. It is associated with that denunciatory article from Pravda in 1937, so it started painfully for Shchusev and ended sadly too. The hotel was dismantled and turned into a replica, similar but not quite the same. At the beginning of the 2000s, the museum tried to fight for the preservation of the authentic building, just as it did almost simultaneously for the preservation of the authentic Voentorg. Both attempts were unsuccessful, and now they show us fragments of the genuine “Moscow” hotel collected during its demolition.

Beautifully arranged in a glass case at the base of the columns are various hotel items, from rosaries and an old telephone to a plaster capital of a pilaster and balusters from the railing. The faceted medallions from the coffered ceiling are on the walls.

Moving on, it should be said that Shchusev’s work on the restoration of cities was not very well-known. Kishinev was particularly important to him; it was where he was born and spent his childhood. Novgorod served as a model for modern ideas about the “Russian spirit” and as a source for the architecture of churches. It’s intriguing why Shchusev did not restore Pskov; it seems to have been historically conditioned. In the annotation to the Novgorod project, Shchusev recommends maintaining the external appearance in the spirit of classicism and Novgorod/Pskov architecture. It makes one want to go to Novgorod and look for such motifs among the Stalinist buildings, but it still seems they are not there.

The Museum

The last hall in the enfilade is dedicated to the museum itself.

There were two museums – initially, of course, there was one, a museum created in the early 1930s at the Academy of Architecture, located in the Donskoy Monastery. Then, in 1945, Shchusev established the second one – the Museum of Russian Architecture. It had a distinct emphasis on identity in its name. In those historical moments, many were thinking primarily about identity (and once again, it raises the question: what would Shchusev be doing now?). The explanatory plaque says that Shchusev expressed his views on the architectural museum as far back as 1919, and he had experience leading the Tretyakov Gallery (in 1926-1928). Shchusev received support for the “public museum” directly from Molotov and, at the same time, obtained the building, the Talyzin House. Over three years, he resettled the communal apartment residents, and in 1948, he opened an exhibition dedicated to all periods of Russian architecture right there, in the enfilade where the current exhibition in honor of Shchusev is taking place. There are rumors that some exhibits were borrowed from the Academy of Architecture’s museum.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

This project became Shchusev’s last: the museum opened in 1948, he passed away in May 1949, and the next day, the museum was named after him.

This story is somewhat intriguing, and hopefully, the museum will continue to tell it. In 1964, the two museums were merged under the name Shchusev, and in the 1990s, the museum moved out of the Donskoy Monastery, settling in the Talizins’ house, where it now feels very cramped, come right down to it

The latticed shelves in the last hall become that almost unverifiable “hook” that connects the exhibition in the Enfilade with its continuation dedicated to Shchusev’s church architecture – similar constructions are installed there, designed for reuse in the future. The museum was the end, and the churches were the beginning, and everything seems to loop.

The Churches

The exhibition of Shchusev’s church design projects, occupying the Aptekarsky Prikaz, is organized by separate curators: the museum’s scientific secretary Yulia Ratomskaya and the deputy director for science Anatoly Oksenyuk. It can be viewed separately because it is very rich – exhibits arranged in two rows, and six new white layouts harmoniously zone the space. It’s a kind of comprehensive textbook on church architecture at the beginning of the century.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

Shchusev also collaborated with artists such as the conservator Nesterov (they fell out when the architect built the Mausoleum) and avant-garde artists like Petrov-Vodkin, Roerich, and even Natalia Goncharova. His first significant work was the restoration of the Church of Vasily in Ovruch in collaboration with restorer Pyotr Petrovich Pokryshkin. In the process of excavation, the foundations of the stair towers were discovered and promptly restored. Shchusev became one of the favorite architects of the imperial family. Later, he built the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent for Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna – a masterpiece of church modernism, a cohesive, romantic, and beautiful work that is universally loved.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Vasily Bulanov / provided by Chart

There are numerous exhibits, but what “holds” the exhibition space is the Nesterov cardboard depiction of the Veil of Veronica, painted for presentation to the Empress Elizabeth and once placed on the facade. It’s a fascinating analogue to modern renders and VR models shown to clients for project presentation and discussion. Its origin in the museum is unknown – likely, it was part of Shchusev’s collection. However, the painting is very “authentic”, solid, and withstands close examination.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia tarabarina, Archi.ru

Equally recognizable from a distance is the Petrov-Vodkin painting: it is known that he was an icon painter by education, but early works are rarely seen, and there isn’t always an opportunity to compare his Trinity with the “Proletarian Madonna”.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia tarabarina, Archi.ru

Some might say there are too many exhibits, but I appreciate the abundance of drawings and sketches, “brought to light”. This includes ornaments, which are a separate theme; you can examine each curl.

Exhibition "Alexey Shchusev. 150". Museum of Architecture, 01.10.2023-21.01.2024

Copyright: Photograph © Julia tarabarina, Archi.ru

In short, this exhibition is a discovery for fans of the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent. Presumably, it is also valuable for church architects and their clients who should visit for guided tours, if only to appreciate Shchusev’s reflections on the freedom of creativity. The development of church architecture in Orthodoxy at the beginning of the century experienced a rise but then stagnated and has yet to break free. While hopes might be unfounded, perhaps the exhibition will help in this regard as well.

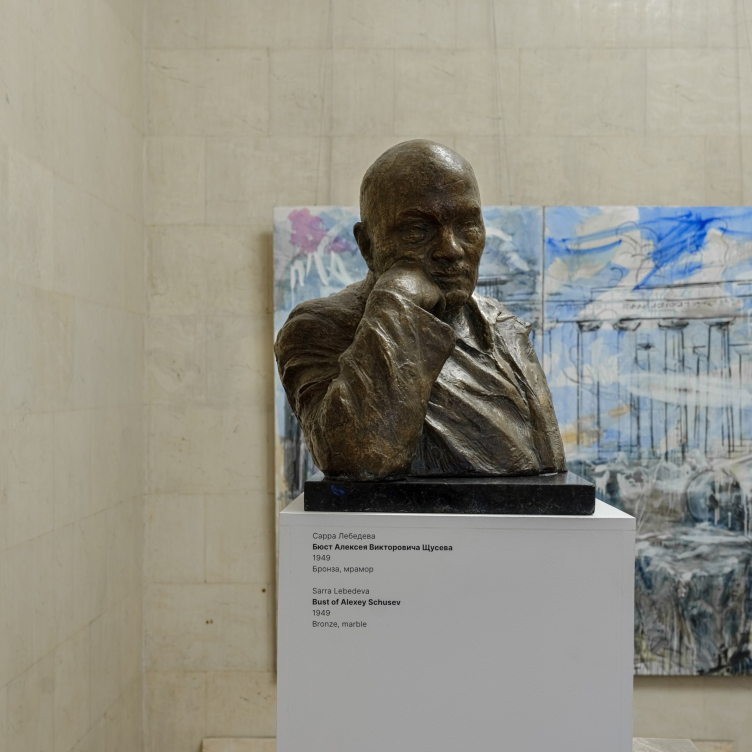

So, who is Shchusev? The exhibition doesn’t provide a definitive answer, and it is not expected to. Instead, it raises many questions, “estranges” the theme, and refreshes perception. Aleksey Shchusev’s figure has fused with the museum and over the years has become somewhat frozen and simultaneously unclear, in contrast to many of his contemporaries who have distinct and defined images. Everyone knows that Shekhtel built mansions, Melnikov sought his avant-garde form, Ginzburg experimented with a house no less innovative than Corbusier’s, and so on. But there is no such distinct anchor for Shchusev; he is distributed among many points: the monastery, the station, the tomb – and loses clarity. It’s akin to the posthumous sculptural portrait on the stairs, where the academician’s eyes are almost invisible, and the face seems erased. The intention in the portrait is clear: Sarra Lebedeva showed how the late Shchusev in 1949 is “breaking away” from his contemporaries, dissolving. And this indefiniteness and this vagueness feel as if they were “stuck” to Shchusev. Either he is a brilliant architect, or a talented administrator, or he fully revealed himself in the church era, or in the avant-garde, or in the Stalinist period. However, the exhibition shows that there were more than just three “reference points”. Perhaps it will become the beginning or the “driver” of a new level of research that will someday explain what kind of person the academician was. Or, conversely, after all the material is collected and analyzed, questions will remain open, and that’s okay.

Meanwhile, although Alksey Shchusev may not have been the sole founder of the Museum of Architecture, he seems to have been the person responsible for placing the museum in the center of Moscow and turning it into a truly significant, exceptionally valuable repository of information on the history of architecture. Honestly, it’s not for the Mausoleum but for the State Research Institute of Art History, Architecture, and Urban Studies that he deserves to have a monument erected in his honor.