from London Polytechnic Institute, now known as Westminster University, Wilkinson traveled throughout Europe and then went on to work for several of the most successful architects in the United Kingdom, including Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and Michael Hopkins. Chris Wilkinson founded his own firm in 1983 and a few years later, he promoted his

collaborator Jim Eyre to become partner and renamed the firm Wilkinson Eyre Architects.

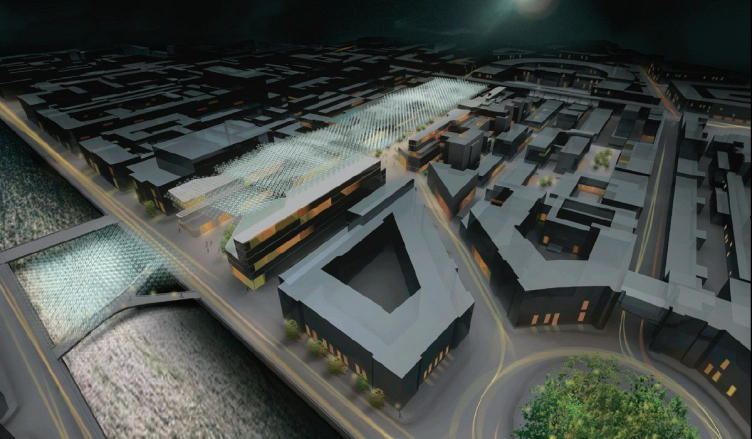

Wilkinson Eyre Architects built a number of widely recognized projects including the Stratford Regional Railroad Station and the Kew Gardens’ Alpine House in London, as well as the National Waterfront Museum Swansea in Wales and the Magna Science Adventure Centre in Rotherham, England. Currently the firm is overseeing the construction of the 437 m tall Guangzhou West Tower in Guangzhou, China. However, the firm’s most celebrated projects are their bridges. The architects have designed over two dozen beautiful kinetic structures in the United Kingdom, The Netherlands, Greece, United Arab Emirates, New Zealand and the United States. Among the firm’s most widely known bridges are the Gateshead Millenium Bridge in North East England and a tiny Bridge of Aspiration, twisting like a ballerina skirt to gracefully connect the Royal Opera House and the Royal Ballet School in Covent Garden, high above Floral Street in central London. Wilkinson Eyre Architects won the coveted Stirling Prize twice (2001 and 2002) for the best building of the year in Britain. In January 2008 the joint team of Wilkinson Eyre and Russian developer giant Glavstroy won the competition to design the masterplan of the Apraksin Dvor district in St. Petersburg, Russia, which will feature a spectacular new footbridge over the Fotanka Canal. I met with Chris Wilkinson in his office in Islington, London where the practice of about 140 architects occupies two full floors in a low-rise modern office building.

Tell me about your winning Apraksin Dvor project in St. Petersburg?

It is a very exciting project for us because St. Petersburg is one of the most beautiful cities in the world, almost every building is a historical masterpiece, and the whole city is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Therefore to build anything new in such a situation is a special challenge. Apraksin Dvor is a run down market area near Nevsky Prospect. The idea is to turn it into high-end retail space, apartments, offices, hotels and museums. It will have a London’s Covent Garden feel to it. We kept all the buildings at the perimeter and removed the run down structures at the core, which will provide an opportunity to have a covered courtyard and streets under a glazed roof with outdoor cafes. We also linked this area to Fontanka Canal and designed a pedestrian bridge on the other side with a cloud-like sculpture. A huge crystalline glass tensegrity roof hangs over the canal and reflects the water and the sky.

How is the relationship with your client Glavstroy developing? Did you notice anything different working in Russia compared to Britain and other places?

The client is very professional. All the expenses at the competition stage were paid for and once we won, they organized

an exhibition of our design in the Union of Architects of St. Petersburg. At the very final stage of the competition we presented our scheme along with Foster and Partners to the governor and jury and then the projects were exhibited for a couple of weeks at the City Hall. What impressed me is that the decision after these two presentations was made on the spot – in just 15 minutes. This would never happen in the UK. Decisions take a long time here.

How familiar were you with the local context of St. Petersburg and how does your project address it?

We spent a lot of time on site and we had all the necessary surveys and historical data, which was very helpful. Personally,

I went there three times. The key idea was to renovate most of the historical buildings and make any new architecture not very noticeable. This is very tricky because if you make new architecture too invisible you might as well just not bother at all. So I think the contrast between old and new is very exciting. I think if you don’t allow for new development a city will die. Cities have to regenerate themselves. But of course, we need to try to keep as much of the historical fabric in tact as we can.

Do you think St. Petersburg is ready for progressive contemporary architecture? How is working in such a sensitive historic city different from working in other places?

Well, there is a reluctance on the part of the people of St. Petersburg to accept any new development. I definitely got that

impression when I was interviewed by the press. My feeling is that new interventions need to be sensitive. The only way you

can explain your intentions is by showing examples and we have worked in historic contexts before. For example, we just

completed the Liverpool Arena and Convention Centre and that is in a World Heritage site. It is a very modern building

and it is very well accepted by locals. We are also building a transportation interchange and a school in the center of Bath.

Do you think it is beneficial for Russian cities to invite foreign architects to build?

I think it is. I think there is a benefit in the mixture of cultures and thinking. London is a very international city and we have

many international architects building here even though we have plenty of great local architects. It provides a healthy competition and it helps to improve the standards, hightening the benchmark of quality. I think it is very good to have some input from outside. Right now many foreign architects are working in London – Jean Nouvel, Renzo Piano, Frank Gehry, Mecano, and of course, we have a lot of major American firms here SOM, KPF, HOK, Swanke Hayden Connell

Architects and so on.

How personally are you involved in this project and how often do you come to St. Petersburg or Russia? What is your impression of the country and its culture?

I am personally involved in the project because I like to design. I’ve been to St. Petersburg four times and I’m going

there again. I visited Moscow twice before the competition. The last time I was there was for a conference on high-rise

buildings organized by ARX magazine. I like the vitality in Russia. When I visit Russia, I always pick up this excitement

and interest in things that are happening so I was really excited to get the project there. I have a particular interest in

projects by constructivists and have visited the Melnikov House. I am also aware of contemporary architecture being designed and built in Russia. I think we will see much better projects in the next few years because there is a very strong desire to move forward. I went to see some towers that are under construction in Moscow with the city chief architect Alexander Kuzmin. He also took me to see the new Christ the Savior Cathedral. It was extraordinary because it was built so quickly.

How do you feel about the fact that your project proposal was chosen over Norman Foster’s, whom you worked for as a young architect?

Well, it is not the first time. Sometimes they win, sometimes we win. We actually have a good record of winning competitions. Today the architecture scene is very competitive, hence one always has to compete for new work.

What was your childhood like and how did you get interested in architecture?

I was brought up in the suburbs of London and my father was a surveyor. I met architects through my father and I think

I was attracted to architecture because of the people I met. They were very interesting to me so I was interested in architecture very early on and art was my favorite subject at school.

Tell me about your path as a young architect after graduating from Polytechnic Institute?

Right after school I worked for one of my professors and three years after, I took three months off to travel and search for

what I wanted to do next. I went to France, Italy and Greece. I wanted to leave London for a while. This was in the early 1970s. While traveling I realized that I wanted to work for either Norman Foster or Richard Rogers. They were not well known then but I wanted to work for them because they were definitely forward thinking. So, I rushed back and applied for work at both places. Foster offered me a job. At that time he had about 30 people. After working there for a few years, Michael Hopkins, who was then a partner at Foster’s, left to open his own firm and asked me to join him. I worked for Michael for five years. Then I was offered a job at Richard Rogers and worked there for a few years. And then there was a point when I decided that if I ever wanted to set up my own practice that was the time. I was 38 years old and I made the decision to start my own practice with no work.

I’m going to be 38 this year. Tell me how do you open your practice with no work?

Well, people were very good to me. Michael Hopkins helped me with work. Also, I continued to work for a while for Richard Rogers. Also, Peter Rice, a well-known engineer from Arup, gave me a couple of projects. One of them was to look after the IBM traveling technology exhibition, which is a building designed by Renzo Piano. This exhibition pavilion was traveling throughout Europe and I looked after it in the UK – putting it up in London and York. Gradually I got more work. All this time I was working by myself. Then I got one person, then another. Initially, I shared space with a former coworker at Richard Rogers. For a while, I had five or six people and then in 1990 we won two major projects for the London Underground Jubilee line – the Stratford Train Depot and Station. Other projects followed subsequently.

You worked for all of the key high-tech British architects. What did you learn from them?

In my last year at university, I went to Richard Rogers’ lecture, which made me aware of new architecture technology,

which I had never heard of before. It was about prefabricated joint construction, new materials, fascinating gaskets and

details and all of those things that seemed so interesting. So, intellectually, I felt that architecture is constantly evolving.

I was always attracted to Modernism, but Modernism that would evolve. Suddenly, I could see that it was the new technology that was going to change architecture. That’s why I was attracted to Foster, Rogers and Hopkins--because of their new approaches, which were still within Modernist principles. When I started my own firm, I had to make some big decisions because I didn’t want to repeat what I had done in the past and it took me a while to find my own approach. I am not really a high-tech person but I am interested in using technology. I like exploring forms, structures and new materials. It is not about just one thing – we do very site specific projects and they are all different because every site is specific and unique.

In one of your texts you say that the philosophy of your firm is about bridging art and science and that in your projects you like to explore the boundaries and crossovers between architecture and engineering. This approach is very characteristic of British architecture. How do you see your role in continuing this tradition and how do you try to distinguish your architectural style?

I think the technical aspects of architecture should not take over. I have a particular interest in aesthetics, proportions and

beauty. Atmosphere is another important aspect that deals not only with how a building looks, but also how it feels. The

objective is always to make architecture uplifting so when you enter the space you feel good and there is a potential to lift

your spirit. Then there is meaning. For me architecture has to have meaning and be relevant. I like to think that there is

always a narrative within a building and it is not just a fancy. For example, in St. Petersburg the meaning is to bridge old

and new, and to create a new life. All old cities need to regenerate themselves and it is the architects’ responsibility to make

that happen. So there are three words that guide me: aesthetics, atmosphere and meaning.

In addition to being an architect, you are also a painter.

I started painting about ten years ago when my wife, who is a professional sculptor, decided to study painting in art

school. I followed what she was learning. I find it very relaxing and stimulating. We have a house in Italy and I usually paint

a lot whenever I go there. I noticed that the paintings I do in Italy are much more colorful than the ones I do in England.

How does painting relate to your work as an architect?

I don’t believe in starting a project with a painting as an inspiration. I think this is where the art and science split. Mental

process in painting is very different to design, which has a very rigorous process, whereas in abstract painting you have to

try to forget everything and just go for it. Yet, when you apply art to design it gives you a risk-taking element and a freedom of spirit. For me this “freeing” of myself is very important. I gain a lot of confidence from my love for painting.

Your bridges are very complex and beautiful. What prompted your fascination with engineering?

It started with buildings. We did a long span for the Stratford Regional Railroad Station which we worked on very closely with our engineers, particularly to ensure that the structure would be very efficient. Based on that project we were invited to take part in a pedestrian bridge competition in 1994 at Canary Wharf, which we won and built the bridge for. Then we were asked to do another bridge competition in Manchester, then another one. So we won five bridge competitions in a row. Overall we have built at least 25 bridges.

Your Apraksin Dvor masterplan in St. Petersburg has a footbridge over Fontanka Canal with a hovering sculpture above it. It is very light, delicate and evocative of Naum Gabo’s kinetic sculptures. Does he or other Russian constructivists play any role in inspiring your architecture?

Definitely. I think what Naum Gabo offers to me inspirationally is this magic quality, which seems to capture light. His

sculptures look very light and delicate. It is very inspiring for our bridge designs and we push our engineers really hard to refine the structure of our bridges.

In your texts you say, “Good buildings have spiritual qualities”. What are the qualities that you would like people to notice and feel in your architecture?

I would like people to feel good. When I say the buildings are “spiritual”, I mean they have the power to lift the spirit. It is

a combination of space, light and acoustics that can have such an uplifting effect. When you go into a cathedral, for example, you get a feeling of being somewhere special. I think all buildings could give that comforting and spiritual quality.

Wilkinson Eyre Architects office in London

24 Britton Street, Islington

April 23, 2008