Vladimir Ginzburg was born July 23, 1930 in the family of the world-famous functionalist architect Moisey Ginzburg. He lived with his parents in the famous Narkomfin House on the Novinsky Boulevard, designed and built by his father, in a communal flat. The friend of Vladimir Ginzburg’s, Yuri Platonov, would later on recall how as children they would go together carrying their milk cans to the communal kitchen to get carry-out dinners for their families. In addition to high school, Vladimir Ginzburg went to an art school. There he made friends with the future director of the State Tretyakov Gallery (1980-1992) Yuri Korolev and the future muralist Evgeny Ablin. In the summer camp, Vladimir Ginzburg met Alla Kireeva, who later on married the famous Soviet poet Robert Rozhdestvensky, with whom Vladimir Ginzburg also maintained friendly ties.

Not so long ago, new details of the Ginzburg architectural galaxy became known. Vladimir Ginzburg’s son, Aleksey, discovered in Minsk 120 projects, signed by a certain Jacob Ginzburg and built from the 1890’s to the early 1920’s. Jacob Ginzburg, Vladimir Ginzburg’s grandfather and Moisey’s father, was an architect or civil engineer, and a very successful one, judging by the fact that he was able to send all of his children to study abroad. In Minsk, they found the tenement that Jacob Ginzburg designed and built, and then lived in one of its apartments.

In 1946, when Moisey Ginzburg died, Vladimir was only sixteen, and when his mother died he was eighteen. He was evicted from the Narkomfin House. For some time, Vladimir Ginzburg lived at the place of his mother’s cousin, Raisa Kantsenelson, whom Moisey Ginzburg had brought over to Moscow from Tbilisi. She studied the history and theory of architecture in the All-Union Research and Development Institute of the Theory of Architecture and Town Planning. Then the young man moved to a room in a communal flat. In that flat, he met the future author Anatoly Zlobin.

The choice of a profession became for Vladimir Ginzburg a natural decision. However, in 1948-1949, the Soviet Union embarked on the so-called “anti-cosmopolitanism campaign”, and he was not admitted to the Moscow Architectural Institute. However, he was still able to enter the Moscow Civil Engineering Institute, enrolling at the Moscow Architectural Institute a year later. Vladimir graduated from Moscow Architectural Institute in 1956; his professor was Mikhail Sinyavsky (the designer of Moscow Planetarium, and a colleague of Moisey Ginzburg’s – editorial note). Vladimir was in the same course with Yuri Grigoryev (the future deputy of the Chief Architect of Moscow Alexander Kuzmin), and Vsevolod Talkovsky.

Early Career. Brutalism

After he graduated from the institute, for some time Vladimir Ginzburg worked in Giprosport, and then he worked in Mosproject for thirty years. He became the leader of the architectural studio when still a very young man, at the age of 29. He headed Studio 19, and later on, when it was merged with Studio 10, he headed Studio 10. In 1958, he got married and in 1959 his daughter Elena was born. In 1968, Vladimir Ginzburg got married a second time, to Tatiana Barkhina, and a year later his son Aleksey was born.

Just like many of the alumni of Moscow Architectural Institute, in the late 1950’s Vladimir Ginzburg chiefly designed community centers of “clubs” as they were called in the Soviet Union. Together with other Moscow architects, he took part in restoring Tashkent after the Great Earthquake, designing the housing sector.

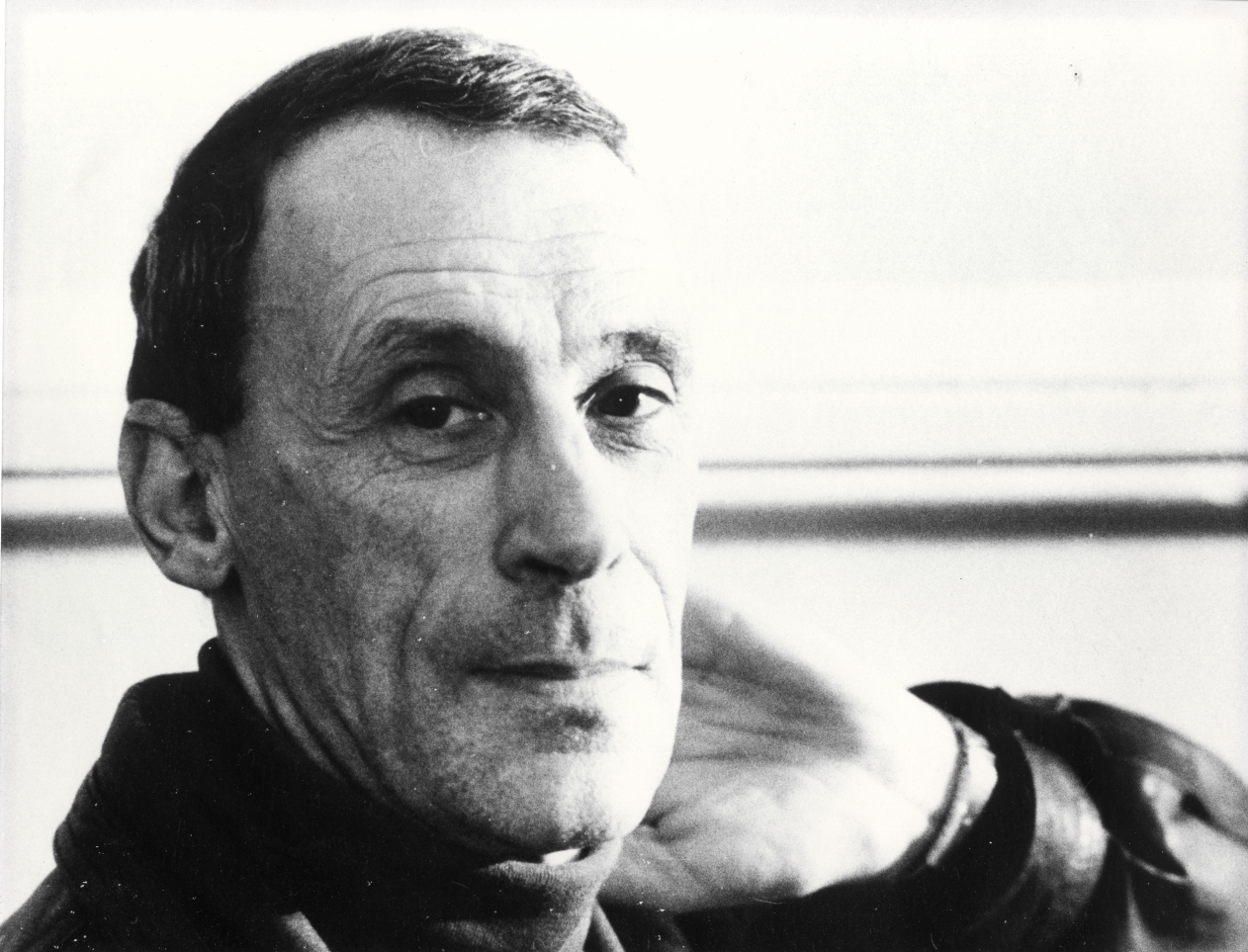

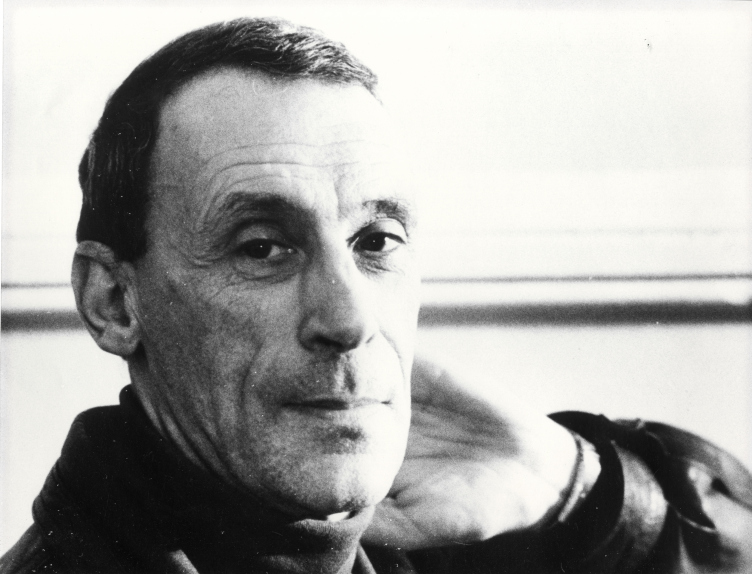

Vladimir Ginzburg

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

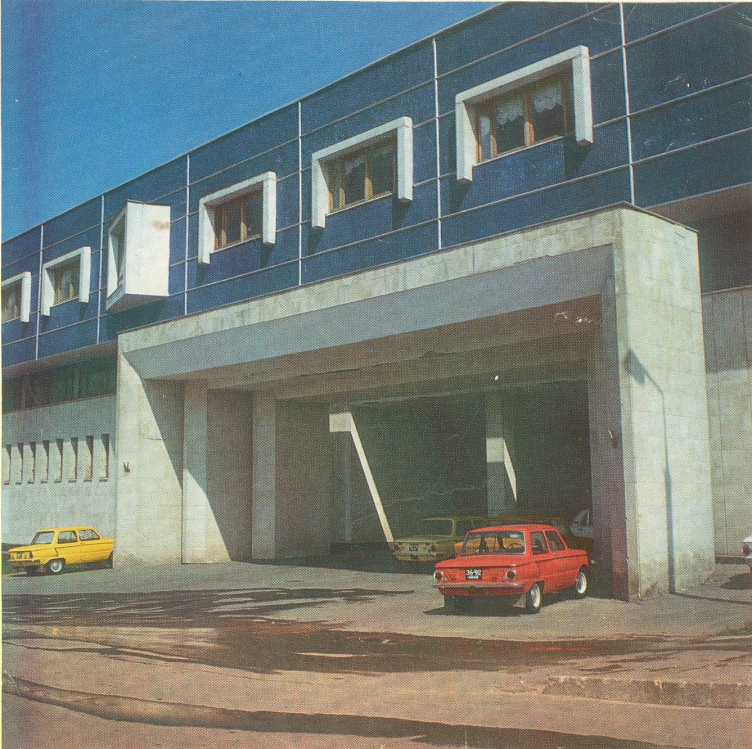

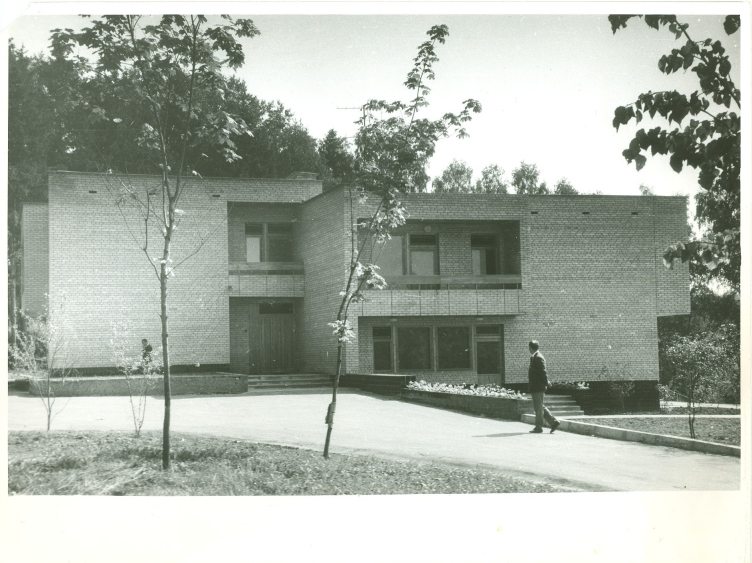

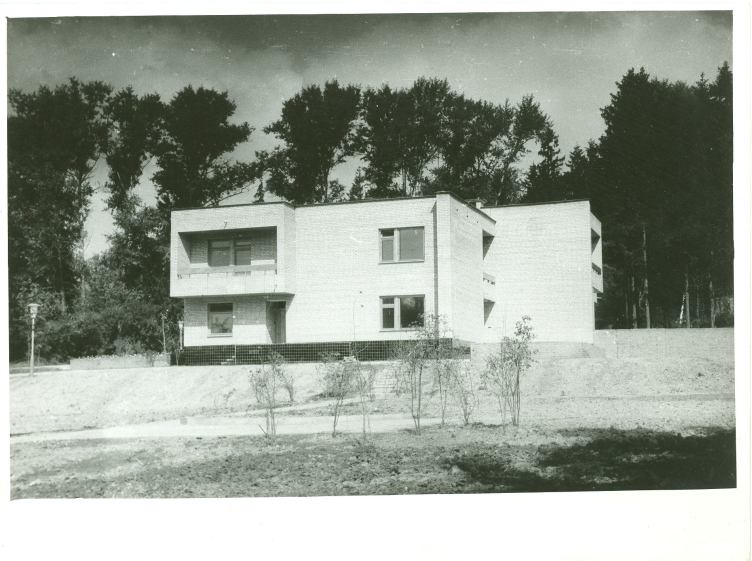

A housing project in Tashkent

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

One of the first public buildings that Vladimir Ginzburg designed is the Shchelkovsky bus terminal in the northeast of Moscow, a classic example of Soviet modernism. Regretfully, this building was torn down in 2017 to be replaced by a new one.

A housing project in Tashkent

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The most interesting project designed by Vladimir Ginzburg in the 1960’s is the Institute of Mechanical Problems that stands on the Vernadskogo Avenue. In the 1960’s the Soviet architects rediscovered the Russian avant-garde art, perceiving it through the prism of the contemporary European architecture. The artistic design solution of the building of the Institute of Mechanical Problems demonstrates the influence of the brutalist architecture.

The Shchelkovo bus terminal

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Institute of Mechanical Problems on the Vernadskogo Avenue

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The 1970’s brought about new opportunities in architecture. In some certain genres the architects were already permitted to design from brick and travertine; a search for new forms begins, even though postmodernism is still a few years away. What served as a testing ground for many architects – including Vladimir Ginzburg – was the Moscow area health resorts. While the health center in Krasnovidovo is all pristine and honest modernism, the health resort in Voskresensk demonstrates vaults and arches. Later on, these ideas will also show through in the Cinema Center. The Health Center of the Council of Ministers is a most interesting example of wooden architecture of the Soviet period.

The Institute of Mechanical Problems on the Vernadskogo Avenue

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The health center in Kransovidovo

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The health center in Kransovidovo

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The health center in Voskresensk

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The health center of the Council of Ministers

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center on the Krasnaya Presnya

The architectural ensemble consisting of the Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission was considered to be his main achievement by the architect himself; for this project, Vladimir Ginzburg was awarded the State Prize of the USSR. Originally, the land site was occupied by the Krasnaya Presnya Baths, and, before beginning the construction, the city had to build a replacement – the bath complex in the Stolyarny Lane – then take down the old bathhouse, and only then build the Hungarian Trade Mission in its stead.

The new building of the Krasnaya Presnya bathhouse, designed by Vladimir Ginzburg, sports a façade with an enormous round window – a dramatic and essentially constructivist element, the only difference being that it was executed in brick.

The health center of the Council of Ministers

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Krasnaya Presnya bathhouse

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

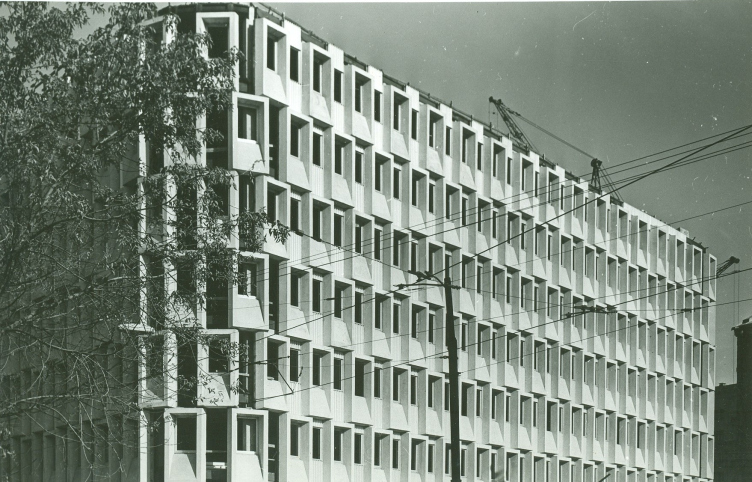

Parallel to that, Vladimir Ginzburg designed the Engineering Building of the Moscow Metro on the Mira Avenue – together with Vladimir Taranov, his friend and chief architect of his studio. The façade design solution is based on a large volumetric pattern of concrete frames placed in a staggered order. The active plastique of the façade surface provides deep contrast of light and shade. The repetitive rhythm puts one in the mind of structuralism, which was popular those years.

The Krasnaya Presnya bathhouse

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Moscow Metro Engineering Building

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Moscow Metro Engineering Building

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The construction of the Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission began in the 1970’s, and these projects were built for 15 years. The ensemble of the Cinema Center is a large public project of a truly impressive scale. Volumes with different functions – the Hungarian Trade Mission, the foyer, and the movie hall – were designed differently plastique-wise, clearly showing the inner structure of the building on the outside. The stained glass window on the Druzhinnikovskaya Street façade enhances the difference between the constituent parts of the complex. The author struggled to get the approval to have his windows made of anodized aluminum, and carefully selected their color.

The Moscow Metro Engineering Building

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The 1970-1980’s saw a trend for making architectural solutions more and more complex. The pathos of the public building is strengthened by the powerful massive wall with loophole. The sinking-in technique leads to an accentuated “constructivist” image of the wall. The hidden columns and exedras create a feeling of power not at the expense of the smooth wall but thanks to its depth. The arched rounded windows accentuate the expressiveness of the apertures, at the same time softening the shape. By the way, the same shape was used in the Metro building, only on a different scale. In the Cinema Center, these elements became gigantic, up to the scale of this enormous public building.

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg

The interior design was dominated by vaulted ceilings – translucent and backlit. The ledges on the façades were matched by exedras on the inside. The interior was adorned by a sculpture by Zurab Tsereteli. Unfortunately, the interior of the building was redone many times. The outward appearance of the Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission also suffered from incompetent operation. Both buildings were coated with travertine. Today, the travertine coating of the Hungarian Trade Mission is covered up by orange ceramic tiles, which is at odds with the original concept of the ensemble.

Postmodernism

The late 1980’s saw the beginning of the postmodernism epoch, with Robert Venturi’s ideas gaining popularity. In the creative work of Vladimir Ginzburg, one can see traces of postmodernism in the first building of the Military Academy in the Blagoveshchensky Alley (1989). But then again, the version of postmodernism proposed here by Vladimir Ginzburg is closer to the solution of a large volume, like the Cinema Center, and is farther away from the trend – which later took root in Moscow – which can be best described as “Luzhkov turrets”. The other building of the Academy, situated closer to the Spiridonovka, was remade into the Russian Foundation for Basic Research building. In 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the construction stopped, and, because the Academy was subjugated to the federal government, the building never was finished.

Approaches to restoring the Narkomfin House

Restoration of the Narkomfin House, the most famous creation of his father, and a fine example of new-type experimental housing, was something that Vladimir Ginzburg took up in the mid-1980’s starting with fundraising at the Soviet art foundations. In 1986, Aleksey Ginzburg joined the project. In 1995, it was planned to attract an American company to the restoration project, and at that time Vladimir Ginzburg, together with his son Aleksey, organized a private studio specifically for restoring the Narkomfin House; however, they were still unable to find the funds up until Vladimir Ginzburg’s demise in 1997.

***

Remembering the personality of his father, Aleksey Ginzburg says: “He was always the heart and soul of the company, be that Mosproject, Sukhanov, or Gagry, in all these creative homes; he always quoted “Master and Margaret”, or other such books, he was sensitive to classical music, would be humming some classical aria, and had a tape recorder collection of Wagner and other composers. He was a man of principles, he was courageous and determined, and he was always decent, never intriguing against anyone. In some ways, he may have been slightly naïve – he never felt the harsh reality of the 1990’s.

Vladimir Ginzburg created memorable buildings that belong to the layer of Soviet postmodernism that became an indispensable part of Moscow cityscape. The cause of restoring the Narkomfin House was picked up by his Aleksey Ginzburg. Finally, in 2016, an investor was found who finally appreciated the potential of the historical building, and now the implementation of the reconstruction project is underway.

The Cinema Center and the Hungarian Trade Mission on the Krasnaya Presnya

Copyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ginzburg