How did this name of “Wing-house” come about, anyway? Roman Leonidov explains that the image of the house sprung from its owner’s personality. He is a prominent figure in the beauty industry, known for his flights of fancy – hence, the “wing” motif. “My client is a very charismatic personality. I was afraid that he would dominate, and, as it turned out, he feared the same thing from my side. And this is why we stayed at a level of mutual respect but we never became soulmates the way I usually do with ninety percent of my clients”.

In addition, the architect wanted to experiment with the back pitch of the roof. The snow load does not scare away anybody these days because it is calculated for any type of roofing. As for the rainfall water, it just goes down the drain. This is how the “bird” form of the roof of the main house came about. It is duplicated in the design of the roofs of the flanks. As for the structure of the “main wing”, one of the elements under the roof is concrete because it carries most of the weight. The other parts of the structure are wood. The roofs of the wings expose bent glued wooden beams: they put an interesting spin on the wing motif.

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

A modern Russian manor estate with a court of honor

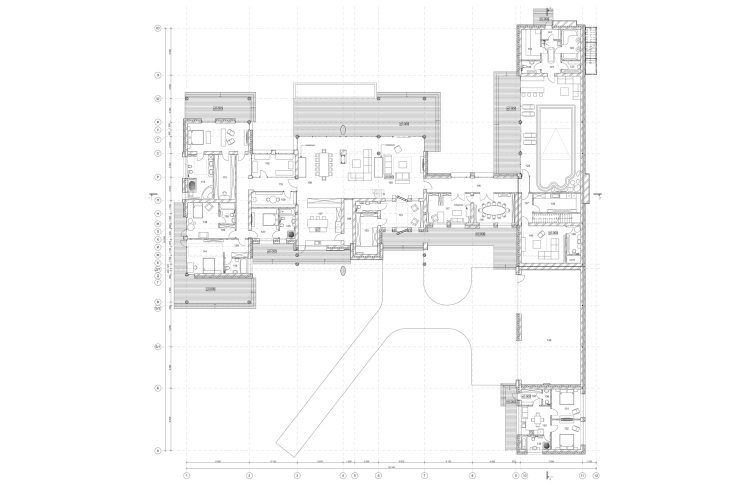

The client wanted a home that would be rather open and representative-looking, yet the same time providing an opportunity for seclusion. Due to the fact that the land plot borders on a forest, there was no problem of shutting out from the neighbors but there was still a task of creating an intimate atmosphere in the yard so that a person who would find himself in there would not feel anybody’s presence. For this reason, the composition of the house includes the central tall part (the main house) and side wings of smaller height, which form the court of honor in front of the main façade. On entering it, one can only see the forest and the land plot. The fence (which is there nonetheless) is hidden deep inside the forest, and there is no feeling of being in a confined space. As for the “court of honor” term, it did not come about by chance. In the functional program of the building, typical of today, Roman Leonidov sees a new type of the Russian manor estate. This includes a rather extended public block: a living room, a kitchen, a dining room, and a health-and-fitness part consisting of a swimming pool, a sauna, and a gym. Fully glazed, the swimming pool grants access to nature, specifically to an open-air terrace with lounge chairs (to this same court of honor, to be exact). This is a whole spa complex, the kind you would meet at a luxury resort. The client wanted this part for his personal use, and for welcoming his guests and business partners.

Plan of the first fllor. Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

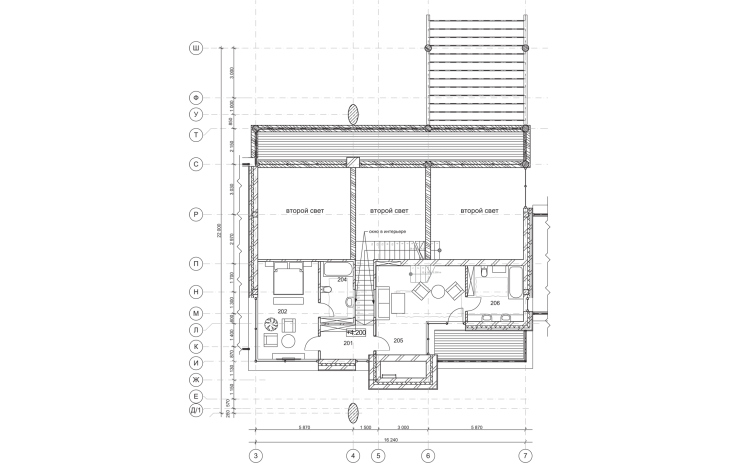

Plan of the second floor. Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Just the way it should be at a manor house, this house has “stalls” in it, i.e. garages for the family’s cars, because if you live in the country one car per family is definitely not enough. The garage also houses the harvesting equipment and the owner’s collection of cars. Totally, this comes together to form a whole car park. The manor estate is a whopping hectare, so the landscape is handled by a gardener, or rather, the local jack-of-all-trades.

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

The main house includes a double-height living room, a dining room, and a master’s bedroom on the second floor. One of the wings includes rooms for the residents and guests; beneath them, there is a spa complex. The other wing includes the “stalls” of the garages, and the gardener’s flat above them. What is interesting is the fact that the overpass leading from the main house to the wing on the second floor is essentially an open-air terrace for everyone to see, from which one can also enjoy the surrounding scenery. The terrace makes the image of the house more open (the usable roof, since it is flat, must be filled with life) but its role of a belvedere is rather representational: as was already said, the court of honor, protected from the outside world, enjoys more popularity here.

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

“At first the I and the client were shocked but then we realized that this thing would be bold and good-looking”

The fashionable black color is in fact a result of a construction mistake. Roman Leonidov: “The paint that we ordered arrived, and it was alright against the waybill. The construction workers started doing the paint job, and then they call us and go: it’s sort of darkish, was it meant to be that way? I instantly come round and see that the wood is now pitch-black! I try to take a shave off the surface, and I realize that this is impossible – you cannot even chip it away. At first I and the customer were shocked but then we realized that this thing would be bold and good-looking. All the more so because he is an emotionally open person, capable of making unexpected decisions! I myself would never have dared to make the plunge but now I see that this was a success”.

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

“I like Fallingwater in terms of composition, but functionally it’s an atrocity”.

Roman Leonidov says that some of his creations were inspired by organic architecture. When asked whether he drew inspiration from Frank Lloyd Wright, he gave an unexpected answer – and our conversation went to a whole new level. “An architect cannot NOT be inspired by Wright. We all are infected by this his “Fallingwater” or “Waterfall villa”. I love it in terms of composition, but functionally it’s an atrocity, a thing in itself. It leaves no room for life. Whatever life there is in it, it only gets in the way of architecture. I am trying to be a modernist like Corbusier or Wright but I can’t seem to be doing very well. Eclecticism is what’s hot right now. At a first glance, modernism seems to have more integrity about it. But, in fact, we do the same decoration stuff that the authors of the late ХIХ century did. It lacks the philosophical prime mover that would push the whole thing forward from inside. It’s just not there. And this is generally the issue with modern architecture. It lacks the integral philosophical construct that would shape up the contents and the form of the architecture. But the tasks that we have to handle are still as important: you need to make the house fit in nicely with its surroundings, ensure the client’s comfort, and achieve the perfect plastique”.

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

The Wing-house successfully solves all these three tasks. As for the comfort aspect, we already covered it. The house also fits nicely with its surroundings thanks to its materials. There are many of them: concrete and wood, stone and brick, glass and stucco. “Yes, it may seem like there are too many different materials used in our house. Had we used fewer materials, it would be more integral and its form would read better – Roman Leonidov says. But what people are after is something that has texture about it, something palpable”. In this case, the architect was very considerate of the human psychology. Wood, brick and stone are used in the bearing structures. The decoration is ruled by plaster and basswood. The vertical towers are covered with sandstone: “not for any functional reason, just for the beauty of it”.

The composition, as was already said, consists of three parts. Where a vertical accent was needed, the stone-covered “Wright” towers appeared – a memory of the “Villa above the waterfall”. (“The vertical wall here is, regretfully, not a fireplace. It’s just that we needed a vertical here”). These towers bump into other elements, one of them piercing the “wing” roof, for example. This technique makes the architectural form particularly dramatic. The tension between the plastique tasks and the function is always there.

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

Wing-house in the Moscow area. Architect: Roman Leonidov © Studio of Roman Leonidov

As is known, “manifesto” houses are rarely lived in. While Fallingwater, according to Roman Leonidov’s confession, is functionally atrocious, in spite of all its artistic beauty (or maybe thanks to it), and Philipp Johnson’s Glass House is also a manifesto that he never lived in, the next question I asked Roman Leonidov was – why does it always happen this way? And it turned out that “the architect’s artistic concept is one thing, and his subconscious is another”. And when I asked if it was worth trying to hear what the subconscious tells you, the answer was as follows: “This is far from easy. It’s great when somebody is around who can help you find your inner freedom. But when the person you have to fight is yourself, it’s pretty tough sometimes. My task was to make sure that my pencil sketch shows through in the end result”. In the Wing-house project, Roman Leonidov was able to do it. What he ultimately got is a house that is integral in its image and comfortable to live in. The artistic concept and the function made peace with each other and are now keeping a good balance.