Before becoming an architect, Leeser was interested in pop art, especially the work of Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys. Thomas grew up in the house designed by his parents – his

mother, an interior designer and his father, an architect, who being Jewish spent the war years in hiding with family in Paris

and opened his progressive architecture practice in Frankfurt after the war. I met with Thomas in his office in DUMBO in

Brooklyn, overlooking East River and stunningly beautiful Manhattan, where all famous New York architects practice,

except one – Leeser.

Tell me about the World Mammoth and Permafrost Museum competition and how did you hear about it?

Well, we first saw it advertised on the internet. We thought – Mammoth Museum, so strange. We were skeptical, but then

realized that the program was not so much about mammoths as a natural history museum, but it is more about the environment – half museum and half research about the environment with laboratory for cloning and DNA study. That

really triggered my interest. In this part of Siberia, there are a lot of mining sites and they keep finding a lot of prehistoric bones and other fossils. There is also a big interest in the scientific community to do more research in this field. There are even talks about possibilities to clone mammoths. But, what is really very interesting is that everything we know about how to build a building does not apply here. For example, the buildings in this area sit on ice. Ice is hundreds of meters deep, so there is no solid rock. It is permafrost zone, which means that a couple of meters below the surface it is always below freezing point.

You did some serious research.

All the research came through my haircutter. Her boyfriend’s grandfather happens to be the ultimate authority on

permafrost. He wrote many books on the subject and has been to Yakutsk many times. It is very difficult to build there and

there are many examples of buildings sliding and collapsing. The problem is that any heat that comes from the building itself

might be transferred to the foundation and melt the ice underneath.

What is the main idea for your design?

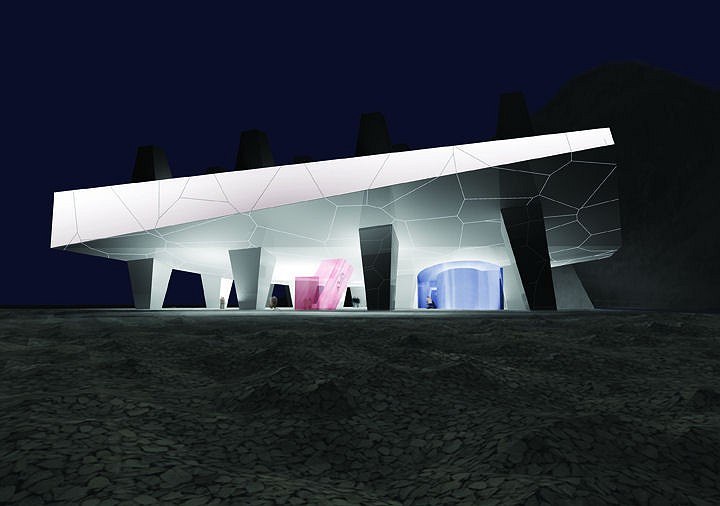

There is no one idea. The site is very unusual. It is completely flat and suddenly, here comes a hill at 45 degrees angle.

Our building is a direct response to this strange landscape. The building responds with a very profound bend up. Then due to permafrost, the building has to touch the ground as little as possible. We proposed legs-like stilts, which is not unusual there. Traditional buildings are built on wooden piles or even on trees. Even large modern buildings do not touch the ground and are built on columns. Once we had these legs, we thought of the inverted condition on the roof since the building should be lit well even if there is a lot of snow accumulation. That’s why we came up with these light wells that look like elephant trunks. These are very simple practical ideas. The building does look like an animal a bit or a bunch of animals. It is interesting that the competition brief asked for the Bilbao effect look. We did not really want to design a strange shape, but the expression of the building is directly linked to its particular site condition, which is strange and unusual. Also because of such extreme climate, we wanted this building to have edgy, rough, heavy qualities. The Museum’s translucent skin is patterned by selfregulating geometries of the permafrost. The envelope is constructed of translucent super-insulated double-glazed façade filled with Aerogel, a densely packed super insulator.

What is the latest word from the Museum and what is the next step?

The last word we heard from them was in November. We communicate only through the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization and the French agency and not directly with the Museum. We heard that there is going to be a new minister of tourism in the Republic of Sakha and that’s why there is this caution towards starting the building process, but we don’t really know.

It seems that this competition is not very transparent. Do you know who was on the jury?

No, I just know that they were all Russian architects and from the local government. Initially, I was all very excited to go to

Siberia and see the place for myself. However, I wanted to see how serious the organizers were so I asked them to pay for

my trip. They did not respond.

There was very little press in Russia about this project compare to how much the competition was covered internationally.

I have no idea why. We are constantly getting requests for information and images for books and magazines. For example,

today we received such request from Italy. I think so far, there was just one request from Russia. I would really want to find

out how we could help to move the project forward.

You told me that you have never been to Russia. However, would you say that Russian art and architecture played any significant role in your education or professional work?

Absolutely! I’m actually very proud of the fact that I went to the same architecture school where Lissitzky went to, The

Darmstadt University of Technology in Germany. So I studied the work of Lissitzky and Malevich. At home, I have a couple of original anonymous figurative Russian paintings from the 1920’s. I’m greatly influenced by Russian constructivist

movement. Also once I came to New York I met people like Bernard Tschumi, who is very influential on my work and especially his interest in Russian constructivists was always very fascinating.

Do you have any favorite architect of that period?

Melnikov, of course is very influential! But you know, I have no idea about contemporary architecture in Russia. Last year I saw Russian contemporary art show at Art Basel Miami. That was so much stronger than installations from other countries.

Tell me about your office. How big is it? Who works here?

We consider ourselves a small office, about 20 people – mostly very young architects who went to Columbia University, but also people are coming all over the world. Some people come just for half a year but most stay at least for a couple of years. It is a very horizontal office. You may come as an intern and find yourself design something to a big surprise and shock. I try to have a similar setting as at school. I lead design studios at Columbia, Pratt and Cooper Union. I don’t really have any particular method of working, designing or teaching. I push students to come up with their own ideas.

You went to Cooper Union just for your thesis year, right?

It is actually a very funny story. I was in the final year at Darmstadt University when I participated in a major national

competition with my friend for Federal Reserve Bank Headquarters in Frankfurt, a huge project. We were awarded the

second place (100,000 Douche Marks) and with a few other entries, we were invited to the second stage of the competition. So we decided to look for a collaborator, possibly a well-known architect who built a bank building before. We went to a few offices in Germany, but didn’t find anyone appropriate. So we came to New York because there are so many banks in New York City! We met with a number of famous architects, but it was Todd Williams, who agreed to collaborate with us. It was so wild – we lived in Todd’s office – at the top floor over the Carnegie Hall where his apartment is now. We had crazy parties and worked on this competition. Todd was teaching at Cooper Union and he said to me – why don’t you apply to Cooper Union? And I said – it is the best school, they will never take me. So he convinced me to

apply. Some time later we found out that our project was awarded the third prize, which for us meant – we lost. But on the

same day I received a letter from Cooper Union that said – you’re in! So I went to Cooper Union and so many years later – I am still in New York.

Did you take Peter Eisenman’s class at Cooper Union?

Yes, I signed up for his class and we read Tafuri. My English was horrible and I said – I can’t take this class, it is so useless. Then Peter asked one of my classmates: “Where is that German kid? Send him to me”. I told him that I did not

understand a single word and he said: “Why does that matter? Do you think these other kids understand anything? You come back to my class and just read it.” I said OK. And a couple of weeks later he invited me to work in his office. He involved me in a competition and we basically worked on it together. I stayed with him for ten years. When I started, the office was just 3-5 people and when I left, it was 35 people and I was the leading designer there all those years.

Did you have any other transformative experience at Cooper Union?

I think the biggest influence was John Hejduk. I remember I was so nervous when I first came there. I thought – oh my god

this a school of the gods, what am I doing here? So I started my thesis year and I had no idea what thesis meant. In Germany, they give you a diploma project, but thesis means something completely different. It was like a dissertation. Your work has to be completely original from ground up and you have to invent your own program. So first, we had to do a warm-up exercise – draw a musical instrument. I went to a flea market in the East Village and bought an accordion – took it completely apart, drew different pieces, put it back together and returned to the flea market. Then we had a review and John Hejduk looked and looked and then said: ”Oh, what a beautiful city!” I was like – it is an accordion, not a city. But

he liked it and I began to see not what was there, but what he saw. In Germany, they would never teach architecture this way. They would say – no, this is too thin and that is too thick. So I got it – I didn’t draw an accordion, I drew architecture! Then the Thesis began. Hejduk came to class and he said: “Here are three words: a fan, a mill and a bridge”. I was like: a fan, a mill and a bridge. What is this? Then I remembered the accordion exercise and I realized that it was not about what he was giving to us, but what we were making out of it. It was about asking the question: why are you here, why do you want to be an architect?

So what did you come up with, a city, a house?

No, it didn’t become anything. It was an abstract architectural construct. I still have it in my office.

Is your current work influenced by Eisenman?

Of course, but right after I left his office I worked very hard to move away from him. It was important for me because I wanted to move on.

In his book “Diagrams” Eisenman writes: “Architecture is traditionally concerned with external phenomena: politics, social conditions, aesthetics, cultural values, ecology and the like. Rarely has it theoretically examined its own discourse, rhetoric and its interiority… Architecture can manifest itself; manifest its own in a realized building.” Do you relate such vision to your own view of architecture?

Yes, but also this is where I wanted to distance myself from him. He likes architecture that examines its own discourse, which is very important and Peter is, in a way someone who invented architecture as a theoretical discipline. But there are so many more things in architecture. There is site, program, client, politics, which are important and they do impact the architect’s work. I think that architects should respond to all of these traditional issues and their responses do not necessarily need to be traditional or expected. I felt that there was no point for me to leave Peter and do something parallel

to what he is doing, which is something that Greg Lynn is exploring. I’m now more interested in how a building is used and

experienced and what it allows you to do with it.

Describe your architecture for me. What are you after?

Let me say what I’m not after. I’m not trying to be at any cost outlandish and different. But, I am after subtle and surprising

experiences and experiencing environment in a slightly new and unexpected way. I’m really interested in how people use

buildings. I’m interested in irony and humor. This building in Russia does look a bit like an animal. It is not necessarily intended that way, but I don’t mind it. I’m also interested in projects that reveal certain aspects of human nature. For example, I’ve done restaurant projects in New York where we played with mirrors. You look at the mirror in a bathroom, but the other side of it is a façade of a building and your private world is completely exposed to the street. It is about confronting people with their own preconceptions and basically, about creating a new context which is surprising and different. So I try to experiment with a certain degree of discomfort. This maybe comes from my heritage of being Jewish

in Germany and the notion of a certain discomfort. Peter has a similar cultural background and it might be one of the

reasons for what he is doing with his architecture. So I try to create projects that are never quite what they seem to be.

What is the single issue in architecture that interests you the most?

To get something built and to do powerful work, but a lot has changed in architecture. When I was just beginning my career, powerful meant something geometrically complex because everything was very simple. Now everything is geometrically complex because of the computers so the meaning of powerful has shifted. My interest is not in how the buildings look like, but in how they are experienced. It is no longer about a wildly complex thing. Since Bilbao, it is too simple and not interesting. Architecture is changing all the time.