Wowhaus came up with a concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment. The customer of the project is "Olimpiysky Complex Luzhniki" JSC, the company that manages the famous sports complex; last year, it organized a tender for reconstructing the swimming complex of Luzhniki; now it is reconstructing the Major Sport Arena for the 2018 World Soccer Championship. Now we are speaking about reorganizing the territory that unites the sports facilities into a single whole - about the weird lowland called "Luzha" ("Puddle") by the locals, the one that any Muscovite is sure to have seen from the "Sparrow Hills" or at least from his car window while driving down the Komsomolsky Avenue - and where most people, excluding those who are really into sports, have never really been.

The architects started their work with a research considering not only the embankment itself but also the 180 hectares of land, circled by its arc in the bend of the Moskva River. As is often the case, a lot of peculiar circumstances came up along the way. The wet grounds of the lowland riverbed need reinforcements, soft ground piles, and such like - but since 1920, in spite of all the difficulties, the city has kept on building stadiums here. The place is nicely located: an hour's walk from the Kremlin, situated in one of Moscow's elite districts - but it is still difficult to get to because it is cut off from Moscow’s center by the Third Transport Ring, and its entrances are not really obvious. It possesses a lot of the characteristic traits of a park, yet does not have the status of one - being listed as a "natural territory". The main peculiarity of Luzhniki is its great sports infrastructure that, however, is only accessible to the professionals and really dedicated amateurs, the holders of various gym memberships. As far as the pre-conditions for the development are concerned, besides the sports facilities as such, there are plenty of them here: the fresh air, and the "Sparrow Hills" metro station nearby, one of whose exits leads directly to the Luzhnetskaya Embankment.

The embankment has also a bicycle track running through it; and to drive on the embankment the drivers need to get a special permission: the automotive traffic is limited. However, making the embankment completely vehicle-free is impossible: it is used by the Federal Security Service.

Right now, the surroundings of the objects that are being reconstructed for the World Championship, including the embankment, look like a beat-up memory of the 1980's Olympics: chippy curbs, cracks in the asphalt, balding lawns and an odd later-on addition of now-dilapidated kiosks. Luzhniki is mostly visited by people that do sports in one way or another - which, on the one side, is a minus, what with the city not making the most of a great piece of natural land, and, on the other side, is a plus: there are no crowds of people - which gives the place an edge over the Gorky Park or the Krymskaya Embankment where on a holiday you can hardly find your way around even on a kick scooter without bumping into someone. And it would even be a bit of a shame to make any changes to this, albeit a bit neglected, quiet little place.

Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

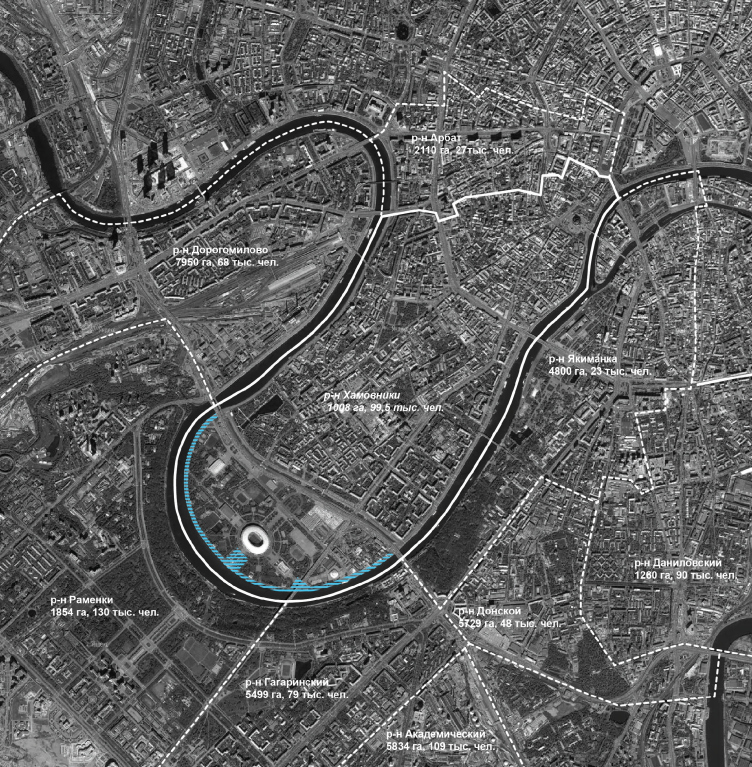

The location plan of the districts adjoining the Luzhnetskaya Embankment. Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

The inside-of-district potential; plan of the new-construction sites inside the district of Khamovniki. Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

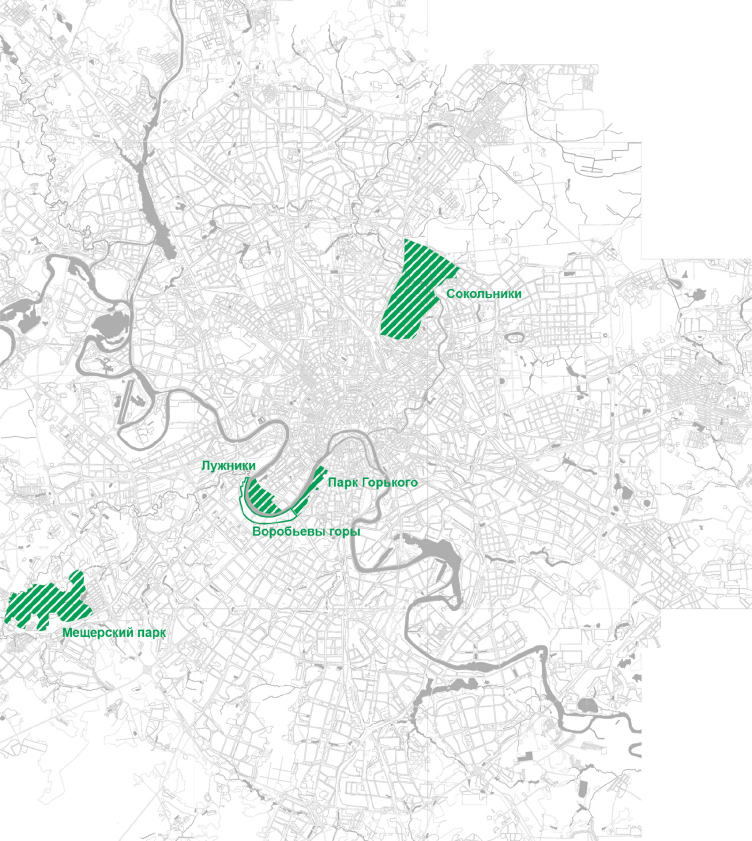

Recreational connection: location map of the Luzhnetskaya Embankment in respect to other parks in the center of Moscow. Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

Potential of the district of Khamovniki: sport and regular recreation. Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

The three parks with which the architects compared Luzhniki in the course of their "competitive analysis": Sokolniki, Gorky Park, and the Meshersky Park beyond the Ring Road. The research showed that Luzhniki have the most developed sports infrastructure.

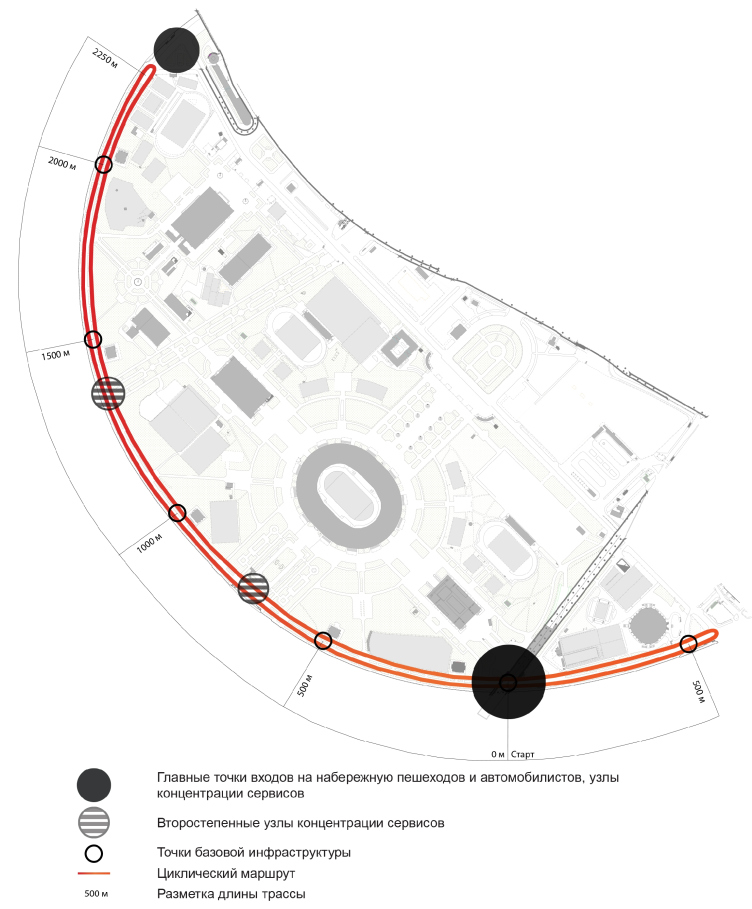

In a word, the architects of Wowhaus did the right thing to refrain from any radical transformations - proposing a lot of little improvements for developing the good things that are already there. These "givens" of the project are, in particular, also different from the Krymskaya Embankment: the latter did not have anything or anyone on it for the exception of the artists from the open-air public art exhibition. As for the case of Luzhniki, however, everything seemingly remains in its place, and its audience will not really grow significantly - mostly at the expense of amateur athletes, and without any radical changes in its specialization. There will be little space to just go around and hang out, while the камеры хранения at the two entrance points are designed to simultaneously serve about four hundred people. "Our concept allows for making the most of the embankment and turn Luzhniki into Moscow's top place for doing sports and active leisure activities" - says one of Wowhaus leaders Oleg Shapiro.

Probably, the consequence of such specialized - and for a large part pragmatic - task as opposed to the hedonistic purpose of the park, the style of the project is really rational and Dutch-style efficient in the best "sustainability" sense of the word: one will not see here any wave-shaped benches or complex flowerbeds, even thought something will be done in that line but this work will be in the background. The architects even plan to keep, though remodeling them, some of the old benches. What decor the place will have is the "trademark" Luzhnetskaya strokes on the asphalt in the spirit of "Roll On, Time" suite and the figures of swallows.

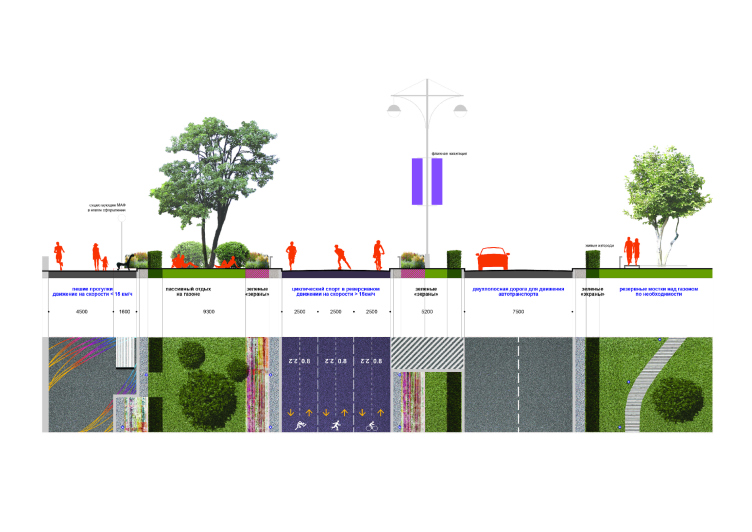

It's not about decor anyway. Presently, there are three asphalt roads, separated by parkways, running along the Luzhnetskaya Embankment: the one closest to the river is the "sport" trail without any intelligible marks on it: it's either a bicycle or a jogging trail with narrow insufficient strips of asphalt left for the pedestrians, no other sidewalks being provided, the other two roads being fully automotive, even though, due to the fact that this is a partially restricted area, there are few cars driving down them. Because of that, everybody moves in his or her own way here - remark the authors in their report: the pedestrians wander onto the jogging/bicycle strip where somebody may be riding a bicycle or roller blades. With this unsafe pedestrian/cyclist situation, four vehicle lanes stay almost idle. Although now the joggers run over the car lanes as well - but then again, this is not the result of space organization, this being their personal decision not to be afraid of an odd car or two.

The architects of Wowhaus proposed to change this lopsided situation and leave only one of the three lanes, the inner one, to the automotive traffic. On the other side, the trail that is closest to the river (the one that is mostly used for jogging now) the architects reserved for walking and "slow" jogging. One could visualize here a mama walking with her baby while their daddy is doing his exercises. The whole "mean line" that was "taken away" from the cars, is now fully dedicated to sports being dissected into as much as six lanes, two directions provided for each of the following three sports: joggers, roller-blades, and cyclists. Thus, the three "cyclic" sports (I'm just wondering to which group they refer the skaters? To the class of the roller blades?) are standing in a close-knit fashion on one asphalt track, like the elements in Mendeleev Table; it is even planned that there will be arrow signs showing the directions and preventing the athletes from getting onto the oncoming lanes. Each lane is about four feet wide.

Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

Profile of the embankment: project proposal © Wowhaus

For marking the trails, decoration, and making other signs, the authors propose two kinds of coverage to choose from, and we learn at this point that the road paint stays for 7-8 month (about which you guess in Moscow every spring), and the thermo plastic - for 4-5 years. Apart from the sport lanes, the authors use the marking paint to make a lot of pedestrian crossings, about every one hundred and fifty meters, spacing them, though, quite rationally: in the "dead-end" east part, there are no pedestrian crossings at all; they are grouped around the metro exits and the small central square.

Of course, the project is not only about the road surface marking alone. Its second layer - after the road marking - is the organization of plants: instead of the "postcard" soviet tulips, the place gets "frost-hardy perennials" and different kinds of multicolored grass that is so popular now, carefully selected to bloom from early spring to late autumn. Besides, now the wide grass lawn with trees is separated from the jogging trail with shrubbery that physically keeps people from treading on the lawn. This sure keeps the grass intact but it is pretty much like a Mona Lisa portrait behind the glass - you can look but you cannot touch. The authors, on the other hand, propose to walk and sit on the grass, and they even organize a few special spots for that. The authors keep but part of the shrubbery covering it with flowers at many places but still use the hedge to fence off the car lane to protect the people from the exhaust smoke. In order not to get on the joggers' nerves with the thought of being responsible for the flowers they tread upon, the architects run along the curb what they call "technical sidewalks", consisting of cobbles and pebbles. The pebbles will be lit by laconic lamps on short lampposts, the lamps turned down so as not to blind the joggers' eyes and throw light on the trail.

Beyond the automotive road, where the athletes are now running on the grass, the broad lawn will get a winding wood-floored path for people to go for walks, the kind that Eugene Ace made in Museon Park. The authors also did not forget about the Federal Security Service - they equipped the road with "standing piers" that, if necessary, can block the road and unblock it automatically.

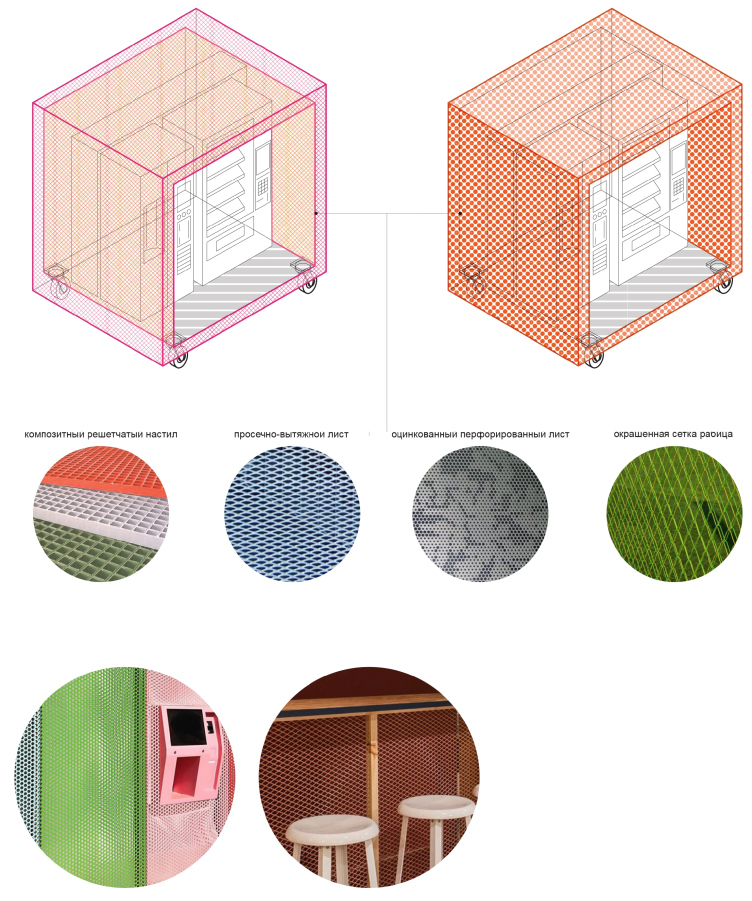

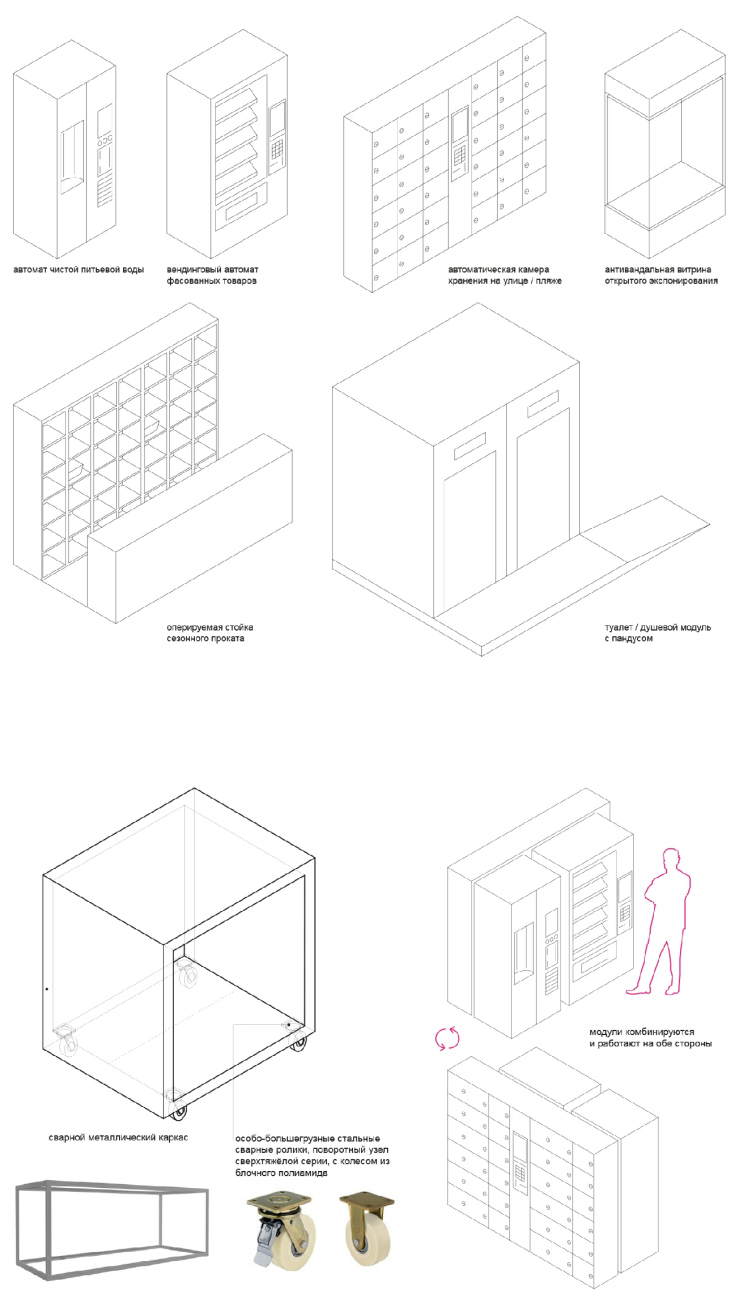

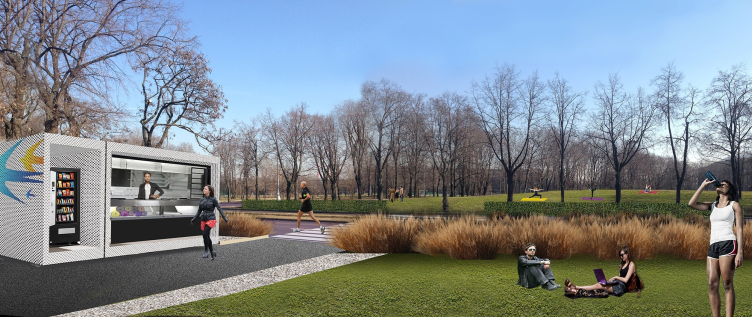

Further on: presently, the embankment looks rather on the dull side, what with its grim benches and dilapidated kiosks, half of them closed up. The architects propose to liven up the track with mobile kiosks performing various functions - from luggage lockers and showers (sic!) to coffee and sandwich vending machines. All of these things (except for the showers, probably) nicely fits into boxes on wheels painted in optimistic colors - as was already said, the kiosks are of the mobile kind. One cannot help seeing in his mind's eye a picture of the Federal Security Service coming through, the piers sliding underground, the people running for dear life, and the kiosks hiding in the earlier secured shelters. Which, of course, cannot really take place IRL - being hooked up to the electric networks and in some cases to the running water, the kiosks cannot go that quickly. The kiosks are manly positioned at the entrances, and the vending machines stand about a hundred meters apart on the embankment itself.

Mobile kiosks: materials. Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

Mobile kiosks: options. Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

And, finally, the project gets three important centers. In the west part of the embankment, closer to the Novodevichy Monastery, the architects organize the automotive entrance making a small parking lot around the triangular lawn in front of the entrance (now it is capable of hosting about as many cars, only parked in a somewhat haphazard way). As far as the space under the bridge is concerned, the architects organize the rough concrete territory next to the exit and under the flyover with the same minimalist means: the lamps under the concrete flyover, a kiosk, a couple of benches, bicycle parking stalls, and marking the asphalt. The third center is, conditionally speaking, the "grand entrance" one, akin to the square opposite the park lying on the axis of the Major Sport Arena. Here one will see a wide pedestrian crossing, tables, a wooden amphitheater on granite steps commanding a view of the river and the Sparrow Hills, like the one that Wowhaus built in the Gorky Park; there are also tables near the cafe by the riverside.

Planning structure of the terrtory. Concept of developing the Luzhnetskaya Embankment © Wowhaus

Entrance from the direction of "Sparrow Hills" metro station © Wowhaus

This project looks both like and unlike the other projects that Wowhaus did for Moscow's public territories, such projects becoming in the recent years the trademark sign of this architectural company. It stands to reason that it continues the ideas that were implemented in the Gorky Park and the Krymskaya Embankment, the Sokolniki Park, and the Sparrow Hills. The authors, however, stress the distinctive features of Luzhniki: these are the sport park, open to everybody but at the same time designed for a moderately sized audience, more of a specialized nature. Probably this is where the peculiarities of the design solution that we already spoke about spring from: very unobtrusively, without any radical changes, it revises the already-existing territory, even keeping the benches - augmenting without destroying and continuing without crossing out what is already there. This is something that I would describe as "town-planning glazing", semitransparent embellishments to the existing picture, of the kind that can be easily rewound back - the kiosks are on wheels, remember? The solution is ostentatiously simple: for framing the kiosks, the architects propose to use not only slotted metal but also even painted Rabitz type steel-wire fabric. The design has absolutely nothing amorous about it, everything is strictly functional: the trails, the backlighting, the locker rooms, and the showers. Looks like an open-air gym - which is, in fact, it is.