Kai Weise

– How have you find yourself in Nepal?

– I was born here, though I'm of Swiss origin and received my Masters degree in Architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich. My father was also an architect. He arrived in Nepal in 1957 for the Swiss Government and stayed on opening his own office. In early 90s after completing my studies, I came back to Kathmandu and started practicing here. Later I was hired as a UNESCO consultant and became involved in conservation of heritage sites from management and planning side. Thus today I define myself as a conservation planner.

Collapsed Chasin Dega at Hanuman Dhoka behind a stone plaque indicating World Heritage status © Kai Weise

- You are also the President of national committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in Nepal. What role has this organization in the country?

– There has been two attempts to establish this organization, I was engaged in the second attempt. The role of ICOMOS Nepal has substantially changed in 2015 after the Gorkha earthquake – it became a platform where we've been debating on the diversity of ideas. The main controversy was on the question of strengthening the damaged heritage sites. One opinion was that if we reconstruct a World heritage site, we should make it stronger. The other approach was that if we strengthen it, then we'll loose authenticity due to using modern materials. Some experts were arguing that we could strengthen it by using other materials and avoiding concrete and cement. The other question under dispute was whether we keep the foundation as it is and build on top of it or whether we need to focus on strengthening the foundation (even by replacing it with the new one).

– What was your position in this controversy?

– Initially I was more concerned with keeping the authenticity of heritage sites but then I started differentiating approaches between 'living' monuments and those that are not. For example, in Bagan, Myanmar, we distinguish active and inactive monuments in a sense that some monuments are used for regular prayers, while others are not. Active pagodas that have certain religious significance are reconstructed and restored, while inactive monuments we tend to conserve.

A view of Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square with the cleared plinth of a collapsed Narayan temple in the foreground with the critically damaged Rana style Gaddhi Baitak. © Kai Weise

– You've been working in Kathmandu valley and Bagan, at two World heritage sites that were heavily damaged during the earthquakes in 2015 and 2016. Do you find it possible to make a strategy for preserving heritage sites in seismic areas?

– That's a difficult question. First of all, we need to get a better understanding of how we deal with that. In most of seismic areas the monuments have survived previous earthquakes. How did they survive the previous earthquakes? What was done previously to ensure that these monuments have certain resistance to earthquakes? We need to go back, study that more and understand that better.

The problem is that we're using the wrong tools. After we study in university, we try to use methods proposed for engineered buildings in assessment of non-engineered structures. Very often it doesn't quite add up. The whole question of engineering and structural assessment is a question of calculating based on certain assumptions. To make these assumptions you need to know the situation. Lack of understanding leads to total miscalculation.

Think about the most important monument in the Kathmandu valley, Hanuman Dhoka, that has totally collapsed after the Gorkha earthquake. There was a Western architect making after-disaster assessment on the site. According to his calculation, the foundation was not sufficient for the structure. We had archaeological research done and we found out that the foundation was in perfect condition and that it was actually three hundred years older than we expected meaning that the foundation was one thousand four hundred years old. I don't think his calculation was wrong, I think the base for his calculations and the method are not appropriate.

A collapsed building in the historic city of Kathmandu. © Kai Weise

– Is it possible to apply experience from other seismic areas worldwide in Nepal or does disaster-relief work always have to be country-specific?

– I think there's a large part that we can learn from each other. For instance, we're working very closely with Japanese experience. A friend of mine from India leads a course in Ritsumeikan University on disaster management for cultural heritage. At that course there are people from seismic areas throughout the world from South America to Southern Europe. The course has proved that certain methods and approaches are universally applicable. However, when it comes to details, for example in terms of materials, we need to be very specific about the location. In Japan it's mostly wooden structures while here it's a mix of wood and brick, in Italy it's mostly stone and brick.

The Swayambhu hillock with the Mahacaitya which used to be an island now overlooks a sea of houses. © Kai Weise

– How have you been involved in disaster-response activities after the Gorkha earthquake?

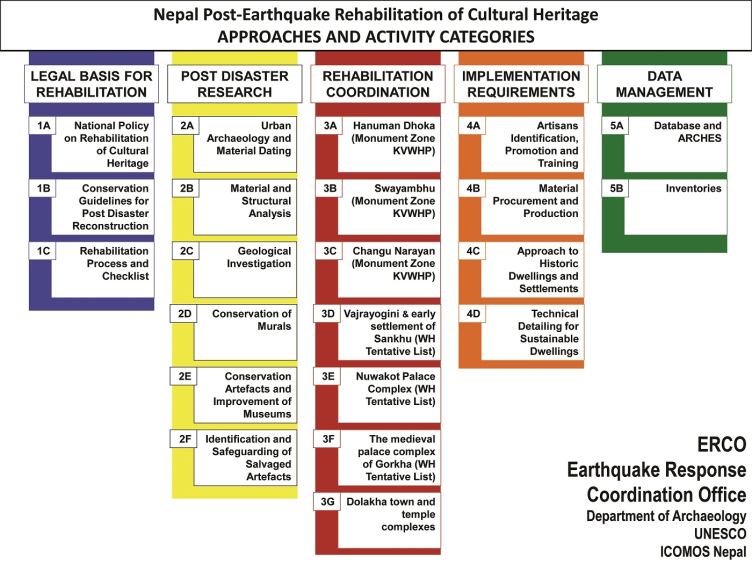

– I was part of the team working on the response and rehabilitation strategy for the culture sector. The earthquake was in April, hence we had only two months before the monsoon, so we needed to protect the damaged monuments from the rain. Then during the monsoon we would have had time for planning long-term disaster-rehabilitation strategy. We had good plans but only parts of it were adopted by the government. For example, the rehabilitation guidelines were adopted but the rehabilitation procedures were not. We were advocating traditional craftsmanship however there was a tendency to go for tendering and using contractors who had no idea of how to work on traditional buildings. I later prepared the culture sector Post Disaster Rehabilitation Framework for the National Reconstruction Authority. This document has been officially published but not implemented.

Salvaging work going on after the earthquake with help from army and police, Patan Durbar Square. © Kai Weise

– How do you assess heritage sites reconstruction after the Gorkha earthquake in Nepal?

– I heard that in Bhaktapur there are a lot of community-led projects working mainly with artisans and the projects seem to be going well. The main problem appears to be when external contractors with no knowledge of traditional construction methods are given the work of rehabilitation of monuments. The contractors are there mainly for commercial purposes and they find employing local artisans too expensive. We have found contractors on site who have been given restoration projects and they have no idea what they are supposed to be doing. This is a sad situation for important monuments.

Shoring to protect the facade collapsing onto the main Hanuman Statue with the intact Agamchhen temple that is raise on timber stilts over the palace. © Kai Weise

– What is the role of international organizations in disaster relief programs?

– There are two sides to this question: what international organizations should be doing and what they are actually doing. In Nepal instead of supporting the national and local government in implementing programs, UNESCO has been focused on actually implementing its own projects. This doesn't seem to be right for me. I believe the local community and especially local artisans should be given priority to do what they can do. International organizations need to support them to implement these locally driven initiatives and help with technical matters. In Bagan UNESCO really managed to support the government and there the relationship between international involvement and national actors is functioning much better. In Nepal UNESCO could have had a similar critical role but it does not fulfil it yet.

The sections of the Hanuman Dhoka Palace which collapsed which included the Tribhuvan exhibit wing and the top floors of the nine-storey tower. © Kai Weise

– What is local perception of this international intervention?

– Locally international interventions are seen as a source of funding. On the other hand, many international organizations seem to prefer competing with local experts and artisans. This has led to some negative circumstances. Thus, there is serious scepticism toward international involvement however there also is dependency.

Nasal Chowk of Hanuman Dhoka Palace with pipe scaffoldings set up to remove museum objects and collapsed elements form the nine-storey tower. © Kai Weise

– What is the specificity of World heritage site management in Asian context?

– I think in Europe it's more based on legal framework, while in Asian countries it's a question of consensus-building and community involvement. First of all, the understanding of heritage has changed. Monument-centric approach is outdated. Heritage is not exclusively for the kings and the rich anymore, it is also for ordinary people. This change requires a change in management system too – from authoritarian one when you put a fence around the site and label that it's heritage, it has to be conserved now, nobody is allowed to get in or touch it, to more inclusive, democratic kind of management system where community is involved. We still are trying to figure out the way how to do it. We need to learn how to combine these approaches. There are still some monuments that we might need to put a fence around to protect them but when we have towns, villages, landscapes considered to be heritage, then we need to have community as a part of the heritage and caretakers. We need to find consensus when community is involved. For example, in Bagan for a long time the monuments were in the center of conservation policies but now we understand that the management shouldn't be only about the monuments, we have to consider the community as well.

– Was this consensus-finding approach successful in Nepal?

– In Kathmandu heritage sites are not as linked to the community, as they are in Bagan or Lumbini. Lumbini, the birthplace of Lord Buddha, perhaps has the most complicated situation due to heterogeneity of communities living there. Till recently there were only Hindu and Muslim groups living there, the Buddhist community came in from abroad not that long ago. When creating a World Heritage site management system, we were identifying which community we are talking about – the local one or the international one. The local community perhaps wants to profit from the heritage, while the international Buddhist community wants to use the site for religious purposes. Therefore, we tried to look at Lumbini in a broader sense – to perceive it as an archaeological landscape that encompasses all early Buddhist sites.

The Swayambhu Mahachaitya showing the temporarily sealed cracks after removal of layers of lime-wash. © Kai Weise

– Some experts find the notion of UNESCO's 'universal value' contradictory (the contradiction lies in over- and under-representation of some countries/regions in the UNESCO World Heritage list). What would be your response to this critique?

– There are several ways of looking at this. If we consider the World Heritage List as those sites that really are of values that are outstanding and universal, then we possibly have many sites that should not be on the list and there are many that are missing. However I believe the World Heritage Convention was established to help conserve heritage and not necessarily to prepare a representative list. As a conservation tool, it might be more effective in some circumstances than in others. We should use it only where needed.

The damaged entrance to Shantipur, the tantric temple which can only be entered by an initiated priest. © Kai Weise

– How do you assess Nepalese representation in World Heritage list - is it adequate to its cultural and natural diversity?

– The World Heritage properties in Nepal do represent the most outstanding and universal heritage properties of the country: Kathmandu Valley, Lumbini Birthplace of Lord Buddha, Sagarmatha (Everest) National Park and Chitwan National Park. There are of course several more sites that could be considered for both natural and cultural or even mixed sites.

– What are the prospects for sites included in the Tentative List? Shall we expect any new nominations any time soon?

– There were seven heritage sites placed on the Tentative list in 1996, one of them being Lumbini which was later inscribed on the World Heritage List. I was involved in the preparation of the 2008 amendment to the Tentative List for Cultural Sites, then we added nine more heritage sites. The tentative list was prepared in a manner that considered diversity and ensuring that all parts of the country were represented. However clearly many of these will never get on the actual World Heritage List.

Potential new properties would be such sites as Medieval Earthern Walled City of Lo Manthang and Tilaurakot, the archaeological remains of ancient Shakya Kingdom. The nomination process of Lo Manthang seems to have come to a halt due to certain community members not wanting to be listed. The listing of Tilaurkot will depend on the outcome of ongoing archaeological investigations. Another very interesting potential mixed World Heritage Site would be Shey Phoksundo National Park and surrounding ancient monasteries that need to be protected from infrastructure development, theft and general deterioration.

The pieces of the mural painting that were salvaged from the front chamber of Shantipur. © Kai Weise

– What is special about Nepal as a country for architects to work in?

– Are we talking about architects who make new things or those who work with the heritage?

– Both.

– They are in two very different situations. Conservation is a sphere where you really need to understand local circumstances and local people. It is very difficult for anyone to just quickly come in and start working here. We're trying to mark off fields where we require international involvement and where it's better to have just the local involvement. Such differentiation allows channelling certain expertise when it's necessary - in methods of conservations, technical and organisational issues. I think in Nepal that distinction hasn't been made clear enough yet. We are having international involvement on the same issues where the national involvement is taking place.

– You are a part of the Society of Nepalese Architects (SONA) and the Swiss Society of Engineers and Architects (SIA). Is there anything in common between these two professional networks?

– I'm not too involved with the Swiss society, even though I'm a member of a section for architects working in foreign countries. That is interesting as Nepal is not a foreign country for me. The SIA works on design competitions and norms. That's something we've been also working on here in Nepal. SONA is a bit politicized, as everything in Nepal when you have numerous people bonded together. On the other hand, one should not underestimate its role. SONA became a place for discussing ethical aspects of architecture in Nepal. There has to be some quality control in Nepal because a lot of constructions are not acceptable even when we have an architect involved. Another important achievement of this professional network is adoption of design competition guidelines that make it possible for young architects to receive commissions and good publicity.

Urban Archaeology, excavation trench through Patan Durbar square. © Kai Weise

Urban Archaeology excavation at Patan Durbar square. © Kai Weise

A woman in traditional attire standing in front of an area of historic Bhaktapur which badly damaged. © Kai Weise

Taking a break next to salvaged wooden elements, Hanuman Dhoka. © Kai Weise

The Indra Jatra chariots in Hanuman Dhoka in September 2013. © Kai Weise

The same location after the earthquake in April 2015. © Kai Weise

People lining up to pray at the Char Narayan Temple in Patan Durbar Square. © Kai Weise

The same Char Narayan Temple that totally collapsed, however the main deity has been reinstated and covered with a temporary shelter. © Kai Weise