|

What we ended up having was an extremely unusual conversation with Dmitry Ostroumov. Why? At the very least, because he is not just an architect specializing in the construction of Orthodox churches. And not just – which is an extreme rarity – a proponent of developing contemporary stylistics within this still highly conservative field. Dmitry Ostroumov is a Master of Theology. So in addition to the history and specifics of the company, we speak about the very concept of the temple, about canon and tradition, about the living and the eternal, and even about the Russian Logos.

The architectural company Prokhram has offices in Moscow and St. Petersburg and specializes in church architecture: church buildings, complexes, interiors, and exhibitions. It works in a comprehensive way, involving colleagues from related fields – glassblowers, mosaic artists, icon painters – and, wherever possible, overseeing projects at all stages. The company organizes round tables and lectures. Recently it has begun publishing the almanac named “Word and Stone”, dedicated to religious art in its various aspects, not only architecture. The most interesting thing, however, is that this is the only architectural firm I know of whose founder and head has a theological education. And not just any education: quite recently Dmitry Ostroumov completed postgraduate studies at the Theological Academy.

Which predetermined my first question.

Archi.ru:

Dmitry, were you a church-going believer from childhood?

Dmitry Ostroumov:

Not at all! You could say that I have been a believer since childhood, but it was not faith in a Deity personified in the figure of Christ. I knew that He exists – the Great Spirit, God, the Creator, the Maker. However, this was based more on personal experiences, and my parents themselves were rather searching: at one point they practiced yoga, at another they went to Protestant communities. From about the age of ten I was involved in various esoteric circles – and later from there I found my way first into hip-hop culture, graffiti, then into the rave underground that was popular in the late 1990s. However, there was always a search for a connection with the Absolute, as I was trying to tune myself toward discovering the higher meaning of life. Later there was even a period when in the morning I would read the Bhagavad Gita, and in the evening Anthony of Sourozh. Yes, there was always an inner existential need to ask about the meaning of existence.

To be honest, I was surprised when this Absolute revealed itself within the Russian Orthodox Church. But I was fortunate: against the background of my sincere searching and turning toward the Divine, I met a number of very interesting people. One of them had once been a major Belarusian banker; he too had followed the path of Eastern mysticism for a time and later came to Orthodoxy. We met by chance – we had a kind of informal discussion group, with other interesting, like-minded people. I was still in my twenties, and they were like older brothers to me – people I could talk to about philosophy and about the Church. In general, life has always brought me gifts in the form of wonderful teachers…

Then I began studying the texts: I read the Holy Fathers – both the ancient writings and the Silver Age authors: Bulgakov, Berdyaev, Solovyov. And it was not so much an intellectual reading as something closely connected with spiritual practices. The Lord granted me very deep states, akin to mystical experience – precisely within the context of the spiritual tradition of the Orthodox Church. So, in fact, I no longer had much of a choice. If the Lord has revealed Himself and shown you the path, you must follow the spiritual way indicated to you. For about ten years I lived in a certain ascetic way: I traveled to monasteries, for a time I lived at the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery, and I often visited Mount Athos. It was a kind of retreat that led to acquiring some deep initiations – seeds of transformation – but that cycle eventually came to an end, and another began, around 2015.

At the same time – and I will repeat myself here – although my worldview is firmly rooted in our Orthodox tradition, it is still quite broad: interreligious, or perhaps, you could describe it as “inter-cultural”. It seems to me that even Eastern philosophy, with its notion of an impersonal Deity, can be used when we speak about the universal Logos as the unexpressed personal principle of the Most High.

So how did you become an architect?

It happened even earlier. Right after school I began studying at BNTU in Minsk, in the Department of Architectural Environment Design. In parallel, already during my final year, I was also studying icon painting and artistic crafts. And while I was in the senior years of my studies, a priest I knew approached me – he needed help with the design of a church, and that project became my diploma work. At that time, I did not even imagine that I would go into church architecture. I was doing completely secular projects – interiors and so on. I took part in the design of a large residential complex.

After that, another parish asked me to help with a church, and later I was approached by a monastery in Godenovo – the place where the well-known 15th-century Cross comes from. Together with colleagues we developed a concept design for a large cathedral there; the working documentation was later prepared by others. It is still under construction – churches are sometimes built for a very long time. And so it went, one thing after another, though at that stage all this was more of an addition both to my regular architectural practice and to my religious life.

When did you receive your architecture degree?

In 2011. And in the same year I entered the seminary at the Trinity-Sergius Lavra. My spiritual teachers blessed me to do so, so that I might perhaps later become a priest. The formal blessing at that time was given by Metropolitan Philaret (Vakhromeyev).

What did your seminary studies give you?

Above all, they systematized my hitherto fragmented theological knowledge.

Why did you not become a priest then?

Perhaps the time simply hasn’t come yet. You have to feel the situation, and feel the right moment. On the other hand, there are many priests, whereas architects who design churches can be counted on one hand. Equally important is the fact that once you enter the priesthood, it entails a certain lack of freedom: it becomes difficult to travel on business or to be fully engaged in architectural practice. And although I am not a clergyman at present, I do serve in the Church: I know the liturgy and try to help in the altar as much as I can… Although I do not rule out that one day I may come to a different rank – we shall see.

Besides, literally in my second or third year at seminary, I found the topic for my thesis – a line of research I have been pursuing ever since, through my Master’s degree and now in postgraduate study.

What is your topic?

In brief: the spiritual foundations of church building.

And who is your academic supervisor?

I began under Nina Valeryevna Kvlividze at the Moscow Theological Academy, and then, during my Master’s and postgraduate studies at the Minsk Theological Academy, I worked under Andrey Vladilenovich Danilov. He trained first as an architect and is now a Doctor of Theology. He studies in depth philosophy, the phenomenology of religious symbolism, the Masonic tradition, and art – while also engaging with a wide range of cultural studies. He scolds me for making my texts too poetic. In scholarship one is expected to adopt a more strictly academic approach – facts and arguments rather than contemplation and flights of fancy.

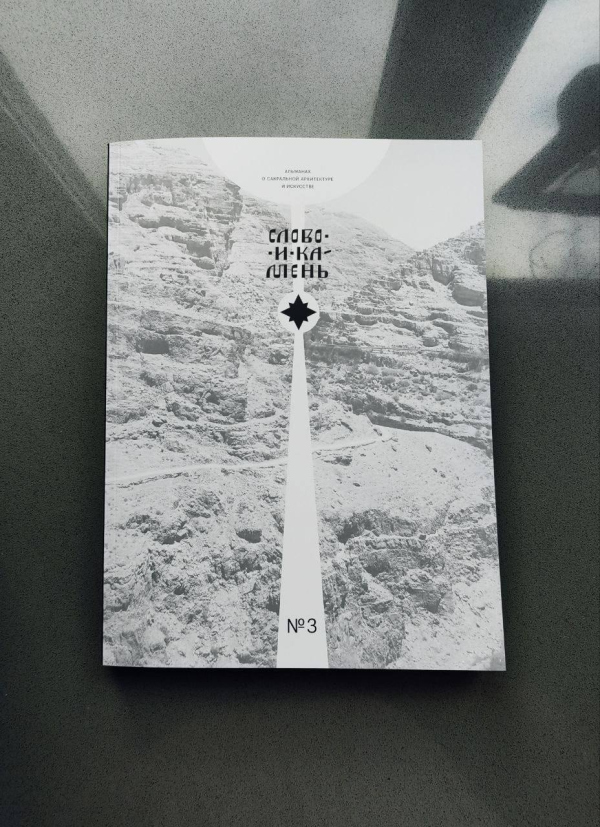

Tell us about your almanac “Word and Stone”. The third issue has now been published. Is this a Prokhram project?

Yes, it’s one of the areas of our work. It grew out of the meetings, lectures, and round tables that we organize. It is a completely non-commercial project, which is why there is always the question of sponsorship to cover the printing of the paper edition – I am convinced that a printed version is essential. For the third issue we launched a fundraising campaign: we needed 800,000 just for printing, but collected ten times less, so in the end we published it with our own funds – though with a delay of several months or something.

The print run is small, and the frequency is irregular, so we call it an almanac, not a magazine. In a sense it is even something of a collector’s publication. We invite interesting people and discuss every sphere of sacred art – not only architecture, but also music, painting; we also turn to Western experience. Of course, most of it still centers on the Russian Orthodox church and everything connected with it – but viewed in a broader context. The texts in the almanac act more like a tuning fork: they help set the tone, immersing the reader in a shared field of art, contemplative reflection, theology, philosophy, theory and practice in architecture, as well as the everyday experience of our colleagues.

Does the almanac in any way support your theological work, or are these two parallel tracks?

Rather parallel. Although, of course, they do overlap. Through the interviews and articles I discover new vectors for my own spiritual and intellectual pursuits – and for my design practice. Some of it then finds its way into my personal work with texts.

So, you are a theologian, and at the same time you work as an architect. How many churches have you designed so far?

Perhaps fifty, if we include all projects – I don’t know the exact number… Of course, far fewer have actually been built.

Do you also do secular design work?

Very rarely. There is simply no time for it. Although today a church – especially in an urban setting – is a complex that already presumes the presence of premises and buildings around the church itself that are not strictly religious in function.

Speaking about your topic – do you have a “super-objective” of any kind? For example, to propose a new image of the church as such?

No, I don’t have such an objective. The task is rather to become part of the general flow of the unfolding of God’s design for the world.

If we speak about the global, specifically creative super-objective of all human activity on Earth, it is, together with the divine personal energy, a synergistic participation in the transformation of cosmic space. And to me, church architecture is the symbolic space of this activity.

A church is a symbol, and a symbol belongs to two worlds. I am deeply convinced that time and space in a church are different. And the liturgical action itself influences the entire cosmos. In the Revelation of St. John the Apostle it is said that when God is “all in all”, everything will be permeated with the uncreated divine energies – then flesh, matter, will acquire a different quality. In this sense, Christianity is the most materialist religion, because it does not deny matter, but speaks of its transfiguration. Many other religions deny matter, considering it to some extent illusory.

And when we create the building of a church or its interior, we are not only creating a space, but also symbolically participating in the transfiguration of the cosmos. To use the language of alchemy, it is the process of the transmutation of the Universe, ongoing since time immemorial – the acquisition of a new quality in the cycles of the ages. A person, together with the Holy Spirit, participates in this, each through their own talent.

And if we talk about the task within the context of our linear lifetime, then it is probably the development of the spiritual tradition and the forms of its expression – in fact, the very life of spiritual principles within culture and art.

What does the development of tradition mean to you?

Today, unfortunately, church architecture is often reduced to a set of architectural quotations and to copying past eras. One can imagine that there is a “brand” of the Orthodox church – it has to be recognizable – and we copy it everywhere in various interpretations, so that everyone can see that this church is Orthodox.

However, the spiritual tradition is a living one. And the forms of its expression may acquire variability, one might say, according to a fractal principle.

Could you expand upon it?

Any fractal contains a certain principle that organizes its structure. It can be likened to the original Sophian impulse that organizes matter. It is unchanging. Theology and canonicity are precisely about this principle.

And the variability of forms, which we also observe in a fractal, is about the development of tradition. Unchanging truths pass from millennium to millennium, yet each time they acquire a new expression. A fractal rather creates a structure, but even within it there is always a moment of the miracle of a new pattern appearing; otherwise it becomes law rather than grace. A natural fractal is always connected with this miracle of the new. A strict mathematical fractal is drier and more rigid. It is like a human being: arms, legs, a head – the structural principle is the same, yet all people are different. Church architecture has for centuries relied on the same principles: the cube, the sphere, the square…

And what about the elongated volume of the basilica?

This way, the basilica illustrates the linearity of time – which, by the way, reflects a particular feature of the Western Church, whose activity is focused rather on the Sermon on the Mount, on social and missionary work. Doing good, opening hospitals, helping the poor. All of this is very important. But it is not the main thing. What matters is the encounter with the very life of divine being. And it is not linear, not somewhere “later”, beyond the threshold of time. Although, of course, we also have a few basilica-type projects.

In the Orthodox tradition, the domed church definitely predominates. It is centric and it illustrates the holistic, integral nature of time. It is built on the synthesis of cubic and spherical volumes, which personify, respectively, matter and spirit. The Orthodox Church bears witness that here and now, without any intermediaries, through our own practice and the sacrament of communion with God, we can meet the Deity directly, feel Him. This is what the philosophy of hesychasm speaks about – in my view, the only true and authentic mystical Christian teaching. It contains the experience of the mystery of death and resurrection, of participation in the uncreated light, the divine. At the point of stillness, at the point of contemplation, we can come into contact with the spiritual world. This is not linearity, but centricity and the quality of being gathered together.

And so, the philosophy of the uncreated light, to which a person may gain access, was rejected by the West still at the dogmatic level. This, with some reservations, also defines the specifics of Western church architecture.

And the Orthodox Church still recognizes it. Our mysticism, spiritual experience and, among other things, church architecture with all the variability of its forms of expression are built upon this.

What can you say about the manifestation of hesychasm through architectural forms? For example, in the 14th century?

If we speak about architecture, then the period when the teaching of St. Gregory Palamas appeared in Rus’ – the time of Sergius of Radonezh and Metropolitan Alexius – is associated with the four best-known “early Moscow” churches. Two of them are in Zvenigorod, the third is the Savior Cathedral of the Andronikov Monastery, and the fourth is the Trinity Cathedral of the Lavra. What matters first of all is the way light enters the interior. There are almost no sources of light in the walls; the main source is the single drum of the dome. A person entering the church directs their contemplation upward – and there, in the dome, is Christ Pantocrator and a row of windows in the drum. Everything else around is what the Holy Fathers called the divine darkness. Or, as in these churches, a half-darkness, a softening of being. One must immerse oneself in it, renounce everything, in order to behold the uncreated light, whose symbol is the daylight concentrated in the drum, or the light of lamps and candles.

Renunciation of everything may resonate with the concept of Buddhist emptiness – the rejection of knowledge and preconceived ideas about the Deity, with blessed unknowing, the path to which lies through the thread of step-by-step knowledge and practice accompanied by inner questioning. All of this is very deep and interesting; the point is that the stages of spiritual experience can be expressed in the symbolism of church architecture. Thus, for example, in the mentioned churches of early Moscow architecture, as we lift our gaze upward, we encounter virtually the only source of light – something that resonates with the understanding of light as always arriving as a miracle of grace amid the blessed unknowing of divine darkness and prayerful contemplation.

Hesychasm was also reflected in the stepped masses, in the “flaming” kokoshniks, and, without doubt, in the religious painting of that period.

Thank you… How do you regard the concept of “canon” in relation to architecture? Nowadays it is used quite often, and, in my opinion, not always appropriately.

Yes, it’s an important topic, and you’re right – there is not always a clear understanding of what it actually is. Strictly speaking, a canon was a rod, a measure of length in antiquity. Later on, it came to mean a measure of pious conduct. Apostle Paul mentions it as a measure of our faith and piety. Later, “canon” came to mean the list of sacred books, the writings of the Apostles, and then the body of rules established by the Holy Councils. But you won’t find a “canon” or “rule” stating what an Orthodox church must exactly look like.

A lot of our contemporaries confuse canon and tradition. A secular client will say “in the style of…”, while a priest is more likely say “according to the canon of…”. “Murals in the canon of Rublev”. The wording is incorrect, but we understand it because we are used to it. That is, canon relates rather to dogma and doctrine, whereas architectural forms or images belong more to tradition. Tradition must not violate the canon; it should strive to express it as fully as possible. The canon speaks about concepts, about theological truths. The expression “architectural canon” would be more appropriately used as “architectural tradition”, with an indication of which one specifically.

You often show the works of contemporary Western architects in your presentations. What do you draw on – them, or Art Nouveau as it existed before the First World War?

Unfortunately, Russian church architects and artists, as a rule, mostly live in a kind of self-contained world. Yes, this world may be beautiful and profound, but we should not forget that the Church has a missionary field, and architecture – the visual language – what is it, if not an instrument of mission?

And yet, almost 40 years of church construction have already passed here, and there is practically no development. Instead, there is some sort of mixing of everything with everything else. At times, such results of “creative search” pop up, that I feel like saying: cut it, folks, it would be better to copy well rather than to try to express yourselves. And the point is not to revive the Neo-Russian style or, on the contrary, to make glass drums and stop there. The point is to create both within the tradition and within the context of global architecture. To work with the environment, with materials, with processes. And for this, of course, one must think out of the box and look out from this world of kokoshniks and vaults at the global architectural context as well.

An architect designs not just buildings – he designs processes; after defining them, he creates space, and only then clothes it in matter, in architecture. A contemporary church in an urban environment is a multifaceted cluster with a large integration zone between the liturgical space and the urban environment. There may be a café, an exhibition hall, a community center. Proper preliminary analysis is 70% of success; we must study the morphology of society and space, and the sociocultural phenomena of a given place. What is sacred may be not only the church, but also the setting for a quiet walk, the museum sphere, a park, a cemetery… We need to peek out a little from our shell, because, in the end, in Christ everything is sacralized; the boundary between the sacred and the profane is perforated. And the context of global architecture – and, following it, of global culture – can set new ideas and directions of development for our Orthodox architecture as well.

And still, if we talk about your own stylistic and visual preferences as an author – what are they?

I feel very close to the “Russian style” of the Art Nouveau period. Not only in architecture – but also in philosophy and art – there is a certain romanticism to that era. And of course, our own Pokrovsky, Shekhtel, Bondarenko, Shchusev. But I also like the Vienna Secession school of fine art – Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele. He has some controversial works, but also absolutely stunning landscapes. He is a wonderful master of the line. For a while I lived entirely within church architecture, but then my perspective widened – and I rediscovered Tadao Ando, Hans van der Laan, Louis Kahn, Mario Botta, Calatrava, Zumthor… There are so many astonishing architectural discoveries there, as well as ways of working with space, material, and detail. Another love of mine is ancient Eastern architecture. Sumerian, Indian, Egyptian. I like their monumentality and grandeur. And of course, I deeply love Russian medieval churches as well – both stone and the wooden architecture of the Russian North. These days the term “archeofuturism” is used more and more often. I think that kind of definition is close to me.

In other words, I am an advocate of ascetic architecture and authentic natural materials. Asceticism gives room for contemplation. If a church interior is all mottled and everything is shouting over everything else, then to pray you just want to close your eyes. The same applies to facades: if they are overloaded with décor, it gets in the way – and sometimes simply turns into cheap stage scenery. There is already enough visual noise in the city; a church is meant to be a place for attentive contemplation, for tuning oneself to a higher principle… And in general, we are called to design space, an environment – not objects.

As I listen to you, I hear the words of a contemporary architect. Tell me, how is your practice organized? I’ve seen mosaic artists and glassblowers in your company, but as I understand it, they work separately?

Yes, these are in fact separate companies – our friends and partners at the same time. The Moscow Mosaic Workshop is headed by Dionisy Ivannikov. The glassblowing studio belongs to Alexey Yatsenko. We experiment: instead of conventional light fixtures we try to create contemporary designer objects in Orthodox churches – again, to reveal the beauty of the material and of how light works. Recently, we created a cycle of original icons together with the icon painter Roman Loboruk for one of our interior projects.

There was a period when we had our own production – machines, carpenters – but we moved away from that. Today, the core staff of Prokhram consists mainly of architects, artists, and designers.

Interior designers or graphic designers?

Both. We are constantly doing projects with the wonderful graphic designer Katya Antoshkina and the calligrapher Marina Maryina. My wife, Ekaterina Ostroumova – with whom, in fact, we originally founded Prokhram – specializes in exhibition design; together we create exhibitions and museums. Our manager, Dasha Chechko, also recently curated one of our museum projects.

We actually have an entire line of work dedicated to exhibitions and museum displays.

I remember the exhibition project in the Round Tower in Tushino.

So far it has remained at the project stage; it was dedicated to the so-called “Russian Logos”, or the Russian idea.

What is the “Russian Logos” to you?

There is a certain Divine plan for the world – and within it, a certain vocation, given as a gift, a potential, to every person. In the same way, every nation has its own vocation, its own path, within the spiritual realization of God’s design for the world. For example, Yuri Mamleyev has a book called Russia Eternal, where he reflects very deeply on Russia’s destiny.

So, I think this vocation is in one way or another revealed in different forms of culture. Naturally, cultures differ. Distilling certain principles from our culture allows us to translate these principles and forms into the language of philosophy – to try to understand “where Russia is flying to”.

And where do you think it is flying to?

Russia is flying to the eschatological Kingdom. Well, I would say that a Russian person endlessly needs something more. Our constant Russian longing and our love for unfinished forms, the pull toward the Beyond, the absence of boundaries and only an endless horizon – all this was something Russian philosophy, and architecture as well, tried to comprehend precisely at the moment of moving away from the Synodal period and returning to the roots. The whole constellation of Russian art and architecture at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries bears witness to this. They attempted to express this Russian Logos. And it seems to me that it is still not defined. Nor can it be defined, given its eternal under-statement. Manifest declarations limit the poetics of contemplative direction. Today people are talking about “identity” on every street corner, but in most cases it’s just hype and profanation…

Returning to our exhibition, we tried to look at the idea of the Russian Logos in three vectors. The first is art, the second is politics, and the third is the spiritual dimension, the religious context. We came up with an interesting take on the 20th century there as well – and, essentially, on goal-setting beyond time… It’s a pity it was never realized, and remained only as a project. Maybe we’ll publish a book.

There is a realized museum dedicated to the Royal Family at the Dno railway station, in the basement level of the church. Katya and I have been studying the Romanovs for a long time, collecting materials; we’ve done several exhibitions – in Pereslavl, in the village of Godenovo, then in Sofia in Bulgaria, and also in Minsk. We did both the visuals and the content entirely. Now we’re preparing a book about them based on the exhibition.

About Nicholas II or about all the Romanovs?

I have long been concerned with the theme of kingship and the theme of self-sacrifice. As well as the spiritual role of the tsar and royal initiation. And I think there is a lack of understanding in our society of Nicholas II and his exploit. And of course you cannot look at him outside the context of all the Romanovs. Outside the context of the oath of 1613, outside the royal Golgotha that laid the foundation for many new martyrs and confessors of the 20th century.

We recently finished a museum of early Christian art in the lower level of the cathedral in Chelyabinsk. That also turned out to be a very interesting museum project.

Do you work only with exhibition design, or do you create the entire exhibition as a whole?

It varies. But the point is that quite often we take on everything, including the exhibition content. For example, there is no Early Christian art in Chelyabinsk – we developed the program, searched for objects, made copies… We worked with Mikhail Bushuev, a well-known St. Petersburg artist and restorer; with Denis Ivannikov’s team we created copies of mosaics; with Aleksey Yatsenko we did a lot of experimenting with glass, recreating frosted ancient vessels; with Yaroslav Starodubtsev and Danila Nikitin we made a replica of the banner of Constantine the Great. And also, we don’t just “outsource” work – what makes our team different is that whatever we do – a building, an interior, or exhibition content – we go into every detail, we work together, we write and draw many things ourselves. It is always collective creativity. Quite often, we take on the entire contract from start to finish. For example, recently in Alapaevsk we created the interior of a church exactly in this way – from pencil sketches to full implementation.

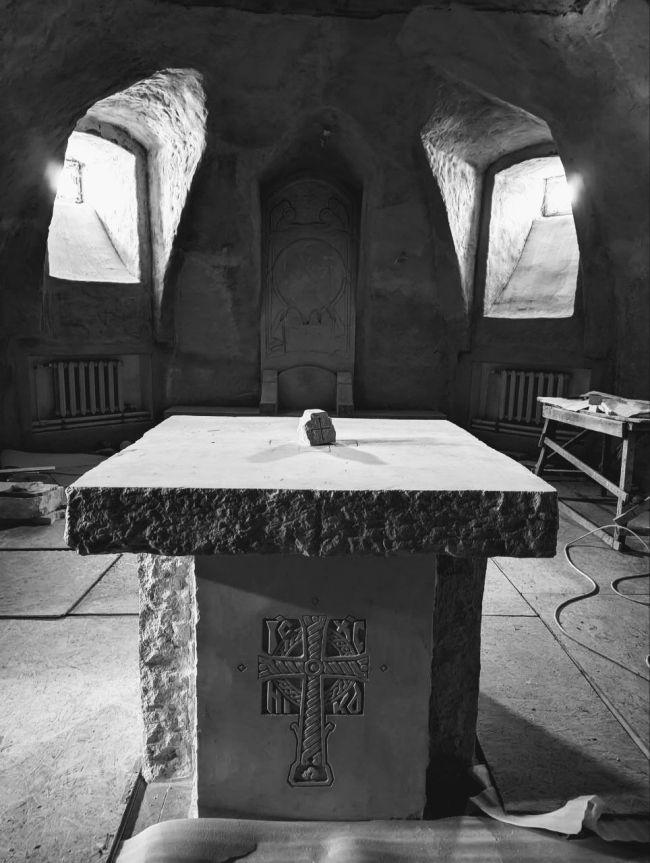

Right now we are working on the interior of a crypt church in the Pskov region; we are doing it in a very archaic, even brutal spirit. The church is dedicated to John the Baptist, and as we know, he lived in caves, in the desert – so our church is turning out “cave-like”: with rough plaster, split stone, mosaics, interesting lighting design – all of this creates a special atmosphere. In fact, atmosphere is probably the main thing that the interior works for.

And we also try to organize exhibitions of Christian art, not only architecture, and bring colleagues together.

There have already been three special projects at “Zodchestvo”; the first one was “alchemical”. There were bricks made of salt blocks, sulfur, mercury in the form of a mirror – everything came together in an installation of a church as the sought-after gold – the philosopher’s stone. Then I did another special project at Zodchestvo where Platonic solids were combined with Gothic stained-glass roses and their color symbolism… Transcendence was represented in the form of a violet tetrahedron. These are all interesting experiments.

Tell us about your favorite projects.

It somehow turns out that they are more often unbuilt or not yet implemented. For example, the Russian Cultural Center in Saudi Arabia. The central element, the pavilion, refers precisely to archaism, to megaliths. Inside we proposed an artificial garden with its own microclimate and four rivers – an image of Paradise.

Another interesting project we recently presented at the latest Zodchestvo festival, in 2025, was a design for five chapels that expresses Christian theology through a synthesis of archaic and contemporary architecture. This was also a special project, which we were able to realize with the help of the KROST company. My wife Ekaterina and I came up with it together: five chapels, each of which can be a tourist attraction in itself and at the same time mark out the space of the entire country. A northern, southern, western, and eastern one – and the central chapel we placed in Altai, which is the geographical center of Eurasia. Each one is a space of silence, a hesychasterion, a place for looking into one’s own soul, for praying to Jesus, and for turning to God. We conceived the central chapel as the Eschaton, connecting it with the teaching about the end times. It is a ziggurat enclosed in a cubic volume; inside there is an altar where an antimension can be brought and the liturgy can sometimes be celebrated. Above it is the open sky – the natural witness of God’s being, as Mircea Eliade wrote. On the sides there are 12 gates, as in the description of the Heavenly Jerusalem in the Revelation of John the Theologian.

Is this your own initiative? A “paper” project?

It is an initiative, yes, but the project is not entirely a “paper” one, as you call it. We are now making efforts to promote it at least a little. Such small objects are not very costly but could be in demand in the context of developing domestic tourism, small settlements, and further promoting interest in our culture and its spiritual foundations.

Speaking of concrete projects, we are now very interested in working with the Krasnodar developer “Tochno”. The architecture there has turned out not entirely contemporary – more southern, likes… But interesting nonetheless! And the church grounds are not fenced off, but form part of a public square – in my opinion, that is very important. I am talking about the church dedicated to the Icon of the Mother of God “The Sign” for the “Pervoe Mesto” residential complex; its construction has just begun.

In Karelia, for the Valaam Monastery, we designed a metochion in the Ladoga skerries – also one of our favorite projects, but it is still in the implementation phase. In it we reinterpreted Russian wooden architecture in the context of frame structures and wooden ventilated facades. But this timber rests on a monumental stone base, like on a rock.

Peterhof – you published it… A grand vision of the rector: a complex next to the St. Petersburg University campus in Peterhof. It is on the outskirts, in a rather depressed area, not in the city center. The priest says there are one or two student suicides a year – it is very tragic… And of course he worries a lot about this place. Hence the idea of a community center for students – one that could be built in several stages: a library, a café, a co-working space. We also designed a rehab center there – a place for treatment of drug and gambling addiction. Such projects can be very much in demand, because they can radically change not just the environment but the overall sociocultural atmosphere.

You work in Moscow and St. Petersburg – you’ve got two offices. Why?

My wife is from St. Petersburg, and I also have roots in this city – my great-grandfather died there during the blockade. But I myself am from Minsk. You could say that “Prokhram” was born there… When our eldest child grew up, we decided that he should go to school in Russia, not in Minsk. By then we were already actively working in Moscow. But for living we chose St. Petersburg.

I handed our Minsk studio over to my colleagues. There is an excellent chief engineer there now, and we fully cooperate. And our family base is in St. Petersburg. In general, I love the North as such – with its lakes, monasteries, moss, stones, the gulf, its special color, and the sky that feels close in every sense. That is how it turned out that we have one studio in St. Petersburg and another in Moscow – but it is one inseparable team.

You said: “Not everything being designed now in the church sphere is close to me”. Speaking of tradition, “canon”, and innovation – what boundary, in your opinion, must not be crossed in church architecture?

Probably everything comes down to the existential experiences a person should have when in a church. A person should feel at home there – an absolute homeland, a sense of eternity, a feeling of the greatness and beauty of God, a spiritual Fatherland. One should feel good there. And of course the church must be built around the liturgical space, which determines it. There are also dogmatic concepts about the human being and the world, which are briefly expressed in the Orthodox Creed.

That is what must not be violated. And if certain design decisions contradict these factors – if, for example, many details are properly observed, but the place still feels uncomfortable – then such a church, in my view, despite its external “canonical” appearance, is not truly canonical. Beauty is one of the names of God, and if the building is simply disproportionate – that is, in fact, not beautiful – then in that alone the canon is already broken. In this sense, Western experience is especially valuable: in the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries many buildings appeared where truly integral, harmonious spaces were created, with excellent work with light and natural materials. However, Western churches often resemble, as the Apostle Paul put it, “temples to an unknown God”, because there is no presence of a personalized Deity there – no Person of the Absolute manifested in Christ. There is no living functional iconography.

And here is something else that is important – dynamism. Alongside stillness, monumentality, even rigidity, there must be, I would say, a kind of contemplative dynamism. Because the cosmos is dynamic, everything is permeated with energy, and the church must convey that. It is like a certain pulse of life, the movement of energies within outward stillness. It is perceived on the level of sensations, but nevertheless architecture, design, and painting all work toward shaping these sensations.

That is to say, there must be clear frameworks of dogma, the unbreakable rules of faith – these are the boundaries. But the forms of expression may be highly varied, and here there are no boundaries, only freedom. In fact, everything is built on a balance between dogma and freedom.

With which of your colleagues do you feel as if you “speak the same language”?

It is hard to say… I think we had a rather deep mutual understanding with Andrey Anisimov when we worked together. We even designed interiors for some of his churches. But times have changed. We are in close contact with Mikhail Mamoshin – he is the chairman of the council for church architecture – a pleasant, charming person, although, as is clear from our projects, our views on architecture differ somewhat. Still, that does not prevent us from working together for a common cause.

Daniil Makarov and Ivan Zemlyakov, the former association “Quadrature of the Circle”, they create experimental projects. Not everything they do is close to me, but the very fact that they are creating precedents for interesting architecture, that they do not stand still, commands respect.

I also like the approach of a little-known architect, Viktor Varlamov. He is an adherent of classical architecture and traditional techniques, and I would say he has a mystical approach to creating a church – which is close to me. He approaches it as the birth of a child; he lives through each church as a story, and may work on a single church for three or four years, whereas our bureau tends to do three or four projects per year. He designs and builds himself, leads the team, carries the stones. We have an in-depth interview with him in the second issue of “Word and Stone”.

Of course, apart from architects there are artists, art historians, theologians, priests with whom we are, so to speak, on the same wavelength… We are, as it were, writing a single collective image of eternity.

Do you think that an architect who undertakes the design of a church must necessarily be a practicing believer of the same confession?

I don’t think it is all that categorical. But one must understand liturgy. However, any secular person can study it if they set themselves the task – in the end, they can consult a priest. Yet there is also something else: when creating a church, an architect enters, let us say, the energetic field of a mystical connection with the Church as such. Not with the organization, but with the Church as the mystical body of Christ. And by creating a church building, he participates in that super-task we spoke of – the transfiguration of the cosmos, which in the end must entirely become Church. He becomes an instrument of the Holy Spirit. Here, it is desirable not only to have an intellectual immersion in the context, but also a practical one – and that already means participation in liturgical life. Even if a person is outside that context, there should be someone who not only consults, but, so to speak, becomes a guide for such an architect into this ecclesial garden. Because a certain spiritual initiation, a connecting, takes place. It seems to me that only from such an engaged spiritual state can a true church be born.

To be honest, I would assign a philosopher – and at the same time a psychologist – to every architectural company.

Nevertheless, there are examples of architects working outside such involvement: as we remember, quite a few significant churches in Rus’ were built by Italians, by Catholics. And the same Tadao Ando I mentioned has designed both Buddhist and Christian temples. It would be interesting to see what he might create as an Orthodox church. I think it would undoubtedly be an interesting experience.

Has anyone ever tried to accuse you of heresy?

Somehow, no – not really. There are people who criticize me, of course. Often, however, it stems from the critics’ own lack of knowledge. At a superficial glance one can certainly say that something in our work is “not Orthodox”, simply because it is unfamiliar – yet if one looks into it, my theological education, thank God, allows me to remain within the bounds of strict Orthodox doctrine.

At the same time, I am a questioning person – open to new things, always learning. I try to listen to what people say. In debatable situations there is the opportunity to consult spiritually experienced people; and, of course, there is also a community of experts – art historians, theologians, practicing priests… It makes me very happy that, on the whole, they are in favor of developing precisely that language of sacred art and architecture in which we are trying to speak.

JordanCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Dmitry OstroumovCopyright: Photograph from the personal archive

NoneCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry OstroumovNoneCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry OstroumovThe trails of Mount AthosCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Rostov the GreatCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Trinity-Sergius LavraCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Tvorozhkovsky MonasteryCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

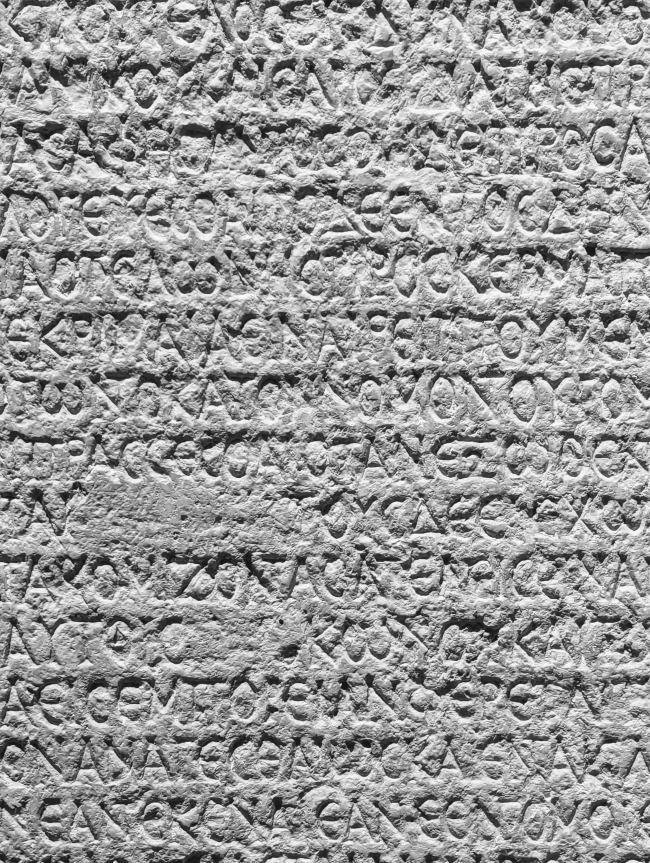

An ancient Sumerian text. Stone carvingCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

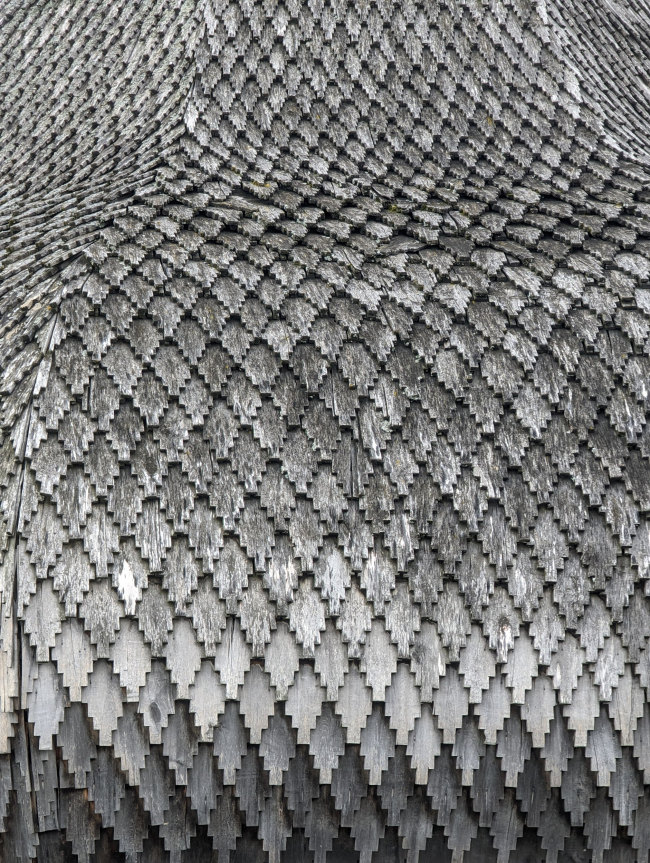

“Word and Stone” almanac, #3Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio“Word and Stone” almanac, #3Copyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioChurch of St. George from the village of Yuksovichi, Podporozhsky district, 1495. village of Rodionovo, Leningrad regionCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

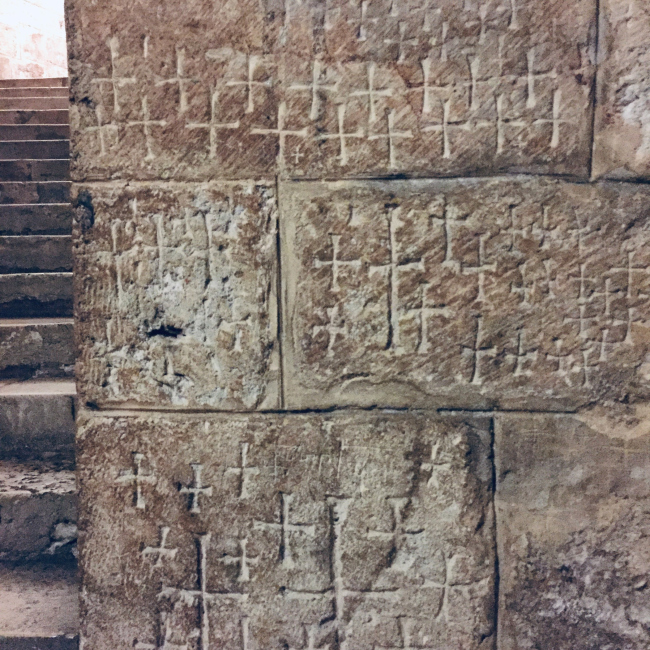

Copyright: © PROKHRAM studioJerusalemCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

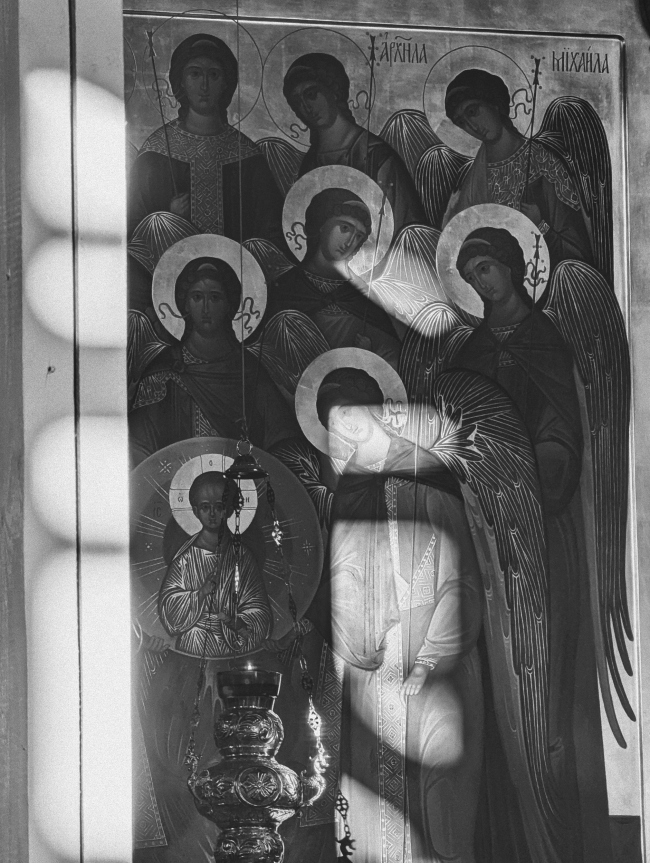

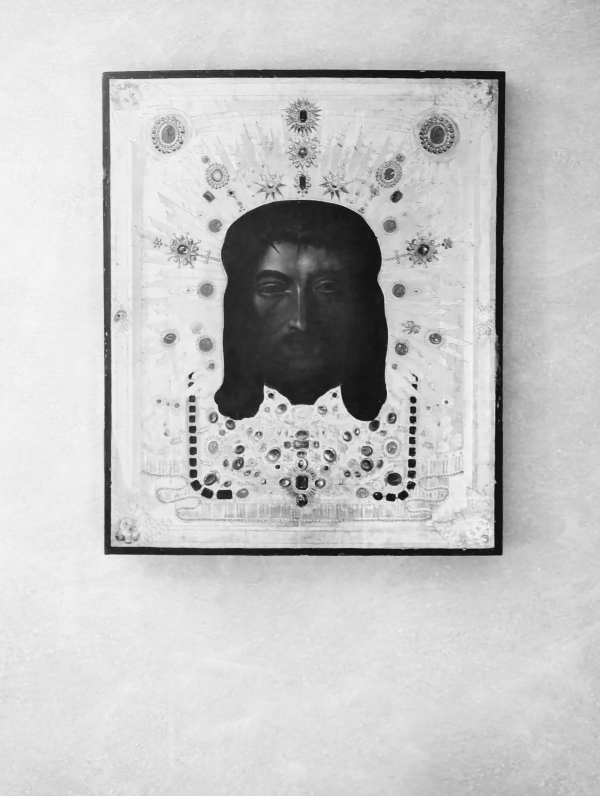

Icon of the Cathedral of the Heavenly PowersCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Copyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioInterior of the church in honor of the Icon of the Mother of God “The Sign”, Krasnodar. PROKHRAMCopyright: © PROKHRAM studio

The church in honor of St. Nicholas in the village of KamenskoeCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Savvino-Storozhevsky MonasteryCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Copyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioA.Shchusev. The project of the Intercession Cathedral of the Marfo-Mariinsky Monastery of Mercy in MoscowCopyright: Yearbook of the Society of Architects and Artists. 1909, p. 132

Copyright: © PROKHRAM studioMosaic in a private chapelCopyright: © PROKHRAM studio. Moscow mosaic workshop, I-glass workshop

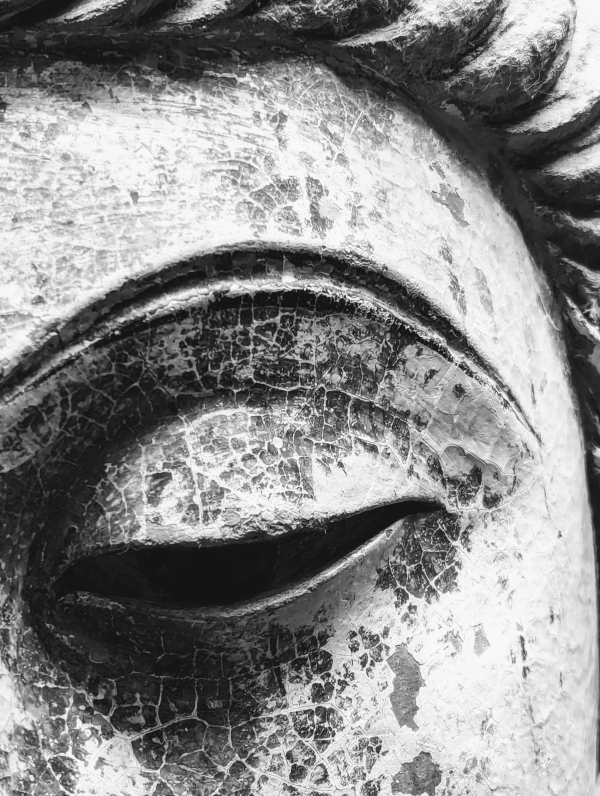

A fragment of an iconCopyright: © PROKHRAM studio. Roman Loboruk

Project of an exhibition “Russian Logos” in the “Tower” center. PROKHRAMCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov / PROKHRAM studioRostov the GreatCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Copyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov / PROKHRAM studioCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov / PROKHRAM studioCopyright: Photo: Press service of the Chelyabinsk ArchdioceseThe throne in the Tvorozhkovsky Monastery. PROKHRAMCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title=" Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title=" Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title=" Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title=" Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title=" Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Copyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioCopyright: © PROKHRAM studioThe State Hermitage MuseumCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Karelia Copyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

The church in honor of the Holy Princess Olga, Minsk. PROKHRAMCopyright: © PROKHRAM studio

Rostov the GreatCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

The lower church in honor of the icon of the Mother of God “August Victory” of the church in honor of St. Alexander Nevsky in Alapaevsk, interior. PROKHRAMCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Copyright: © PROKHRAM studioIcon painter Roman Loboruk at workCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Easter ProcessionCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Ostroumov

Dmitry OstroumovCopyright: From the personal archive

|

Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">

Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">

Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">

Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">

Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">

Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="Five experimental chapels. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">

The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio"> The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">

The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio" title="The temple complex in honor of St. John Chrysostom, Peterhof. PROKHRAM Copyright: © PROKHRAM studio">