|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 14.07.2021 | |

|

The Strategy of Transformation |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

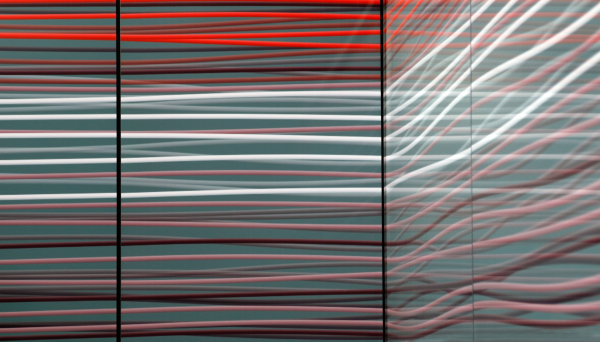

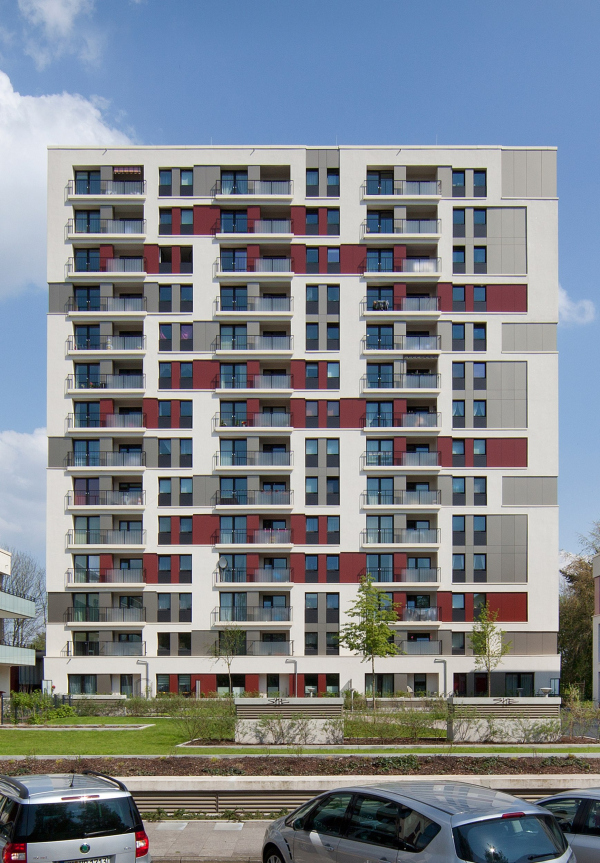

| Studio: | |

| Tchoban Voss Architekten | |

|

In this article, we are publishing eight projects of reconstructing postwar Modernist buildings that have been implemented by Tchoban Voss Architekten and showcased in the AEDES gallery at the recent Re-Use exhibition. Parallel to that, we are meditating on the demonstrated approaches and the preservation of things that architectural legislation does not require to preserve. The show took place in Berlin’s AEDES Gallery in late June / early July. The relatively small exposition featured works by Tchoban Voss Architekten, united by the theme of reconstructing postwar Modernist buildings. Re-Use exhibition in AEDAS gallery, Berlin, 2021Copyright: Photograph © Klemens RennerThe exhibition included 8 implemented reconstruction projects: 3 in Hamburg, 3 in Berlin, and 2 in St. Petersburg. One thing that all these buildings have in common is that, although they could have been legitimately torn down, the decision to preserve the constructive basis, and sometimes even the imagery, was made by the architects who asked their clients to treat “what’s already been built” carefully, ecologically, and cost-effectively. Re-Use exhibition in AEDAS gallery, Berlin, 2021Copyright: Photograph © Klemens RennerIn their entirety, the showcased projects demonstrate a whole range of individual approaches to renewing Modernist buildings, varying in accordance with multiple factors, from the architectural character of the buildings to their geographical location. With the authors permission after the completion of the exhibition we are publishing the “contrastive pairs of the buildings before and after the reconstruction. Conservation A vivid example of conserving a Modernist architectural solution is presented by the reconstruction of the office building at Ernst Reuter Platz in West Berlin. After the renovation, the massive volume with laconic ribbon windows and large cantilevered structures looks exactly as before – as if all the architects did was give the building a good washing. Meanwhile, the reconstruction brought out the characteristic properties of modernist aesthetics – it became transparent, mathematically clear and even “cool-looking” due to the combination of white stripes and bluish glass. The work was finished in June 3030, and the authors described it as “…full clearance, repair, partially new construction”. One must note that in this particular case the original building was good enough as it was, and pay tribute to the authors’ instinct that prompted the path of careful preservation.  The Ernst-Reuter-Platz 6 building before the reconstruction. Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Lev Chestakov Reconstruction of the building at Ernst-Reuter-Platz 6. Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Lev ChestakovMultiplying The office building in the southwest of Berlin, in the area of Blissestraße, built in the 1970s, before the renovation looked significantly heavier than the preceding example from Ernst Reuter Platz. The fractured rows of small windows and the heavyweight side ends of a “standard” appearance would look better on some industrial building than on a crossing of two important streets of a big city (the Brandenburg Avenue comes here). In addition, the neighboring buildings of the same 1979s look much more elegant, their windows being larger, their bottom floors formed by galleries on slender pillars.  The Blissestrasse 5 in Berlin before the reconstructionCopyright: Photograph © Philipp Bauer Reconstruction of the building at Blissestrasse 5, Berlin. Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Klemens RennerAfter the renovation of 2017-2020 that was done at the commission of Becker & Kries, the western wing, the one facing the city, got a new version of facades – now they rhyme with the design solution of the Commerzbank across the street, developing its aesthetic in the direction of even more white and playing with the asymmetric shape of the black metallic frames, particularly flashy when viewed from aside.  Reconstruction of the office building at Blissestrasse 5 in Berlin. Tchoban Voss Architekten, completed in 2020Copyright: Photograph © Klemens Renner Reconstruction of the office building at Blissestrasse 5 in Berlin. Tchoban Voss Architekten, completed in 2020Copyright: Photograph © Klemens Renner Reconstruction of the office building at Blissestrasse 5 in Berlin. Tchoban Voss Architekten, completed in 2020Copyright: Photograph © Klemens Renner Reconstruction of the office building at Blissestrasse 5 in Berlin. Tchoban Voss Architekten, completed in 2020Copyright: Photograph © Klemens Renner Reconstruction of the office building at Blissestrasse 5 in Berlin. Tchoban Voss Architekten, completed in 2020Copyright: Photograph © Klemens RennerIn addition to the facades, the architects also renewed all the engineering systems, reconstructed the building’s underground parking garage, added a fire-escape elevator and the forced ventilation of the fire staircase. The roof became operational. The architects also designed and realized the interiors for the new major renter, the company ITDZ-Berlin, which now occupies the whole building. The ITDZ building on Blissestraße is an example of significant intervention, and, essentially, complete reconstruction that included changing the facades and remodeling the interiors. As one can easily notice, however, all of the changes were made within the framework of the stylistic paradigm of the 1970s – because they imbue the imagery of the neighboring buildings, aiming at creating an urban ensemble with integrity of its own. As a result, the aesthetics of the seventies, prevailing in this part of the city, are accentuated and even multiplied in the new version of the facades – with some adjustment for the subtleties of modern taste, of course. Decoration The textile factory, built in 1966 in the northwest outskirts of Berlin not far from the airport, had already been reconstructed once into an office building: at that time, it received glass insulation units and “fur coat” stucco. The next reconstruction, designed by architects Tchoban Voss, was implemented in 2013–2014 for FOD Properties.  The building of the textile factory in Berlin before the reconstructionCopyright: Provided by Tchoban Voss Architekten Reconstruction of the textile factory in Berlin. Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Greg BannanIn this case, due to the absence of any however little influential architectural environment, the Tchoban Voss architects took the path of manifesting an internal thematic context – they played on the memory of the original function, turning the facade, by using patterned aluminum panels, into a kind of interlacing of multi-colored threads. Interestingly, the prints are designed in such a way that the threads of different colors look as if they “hover” in space, twitching a little, like they would on a loom. The large (and designed in the same way) sign Tuchfabrik (“Textile Factory”) above the entrance enhances the importance of remembering the history of this place and puts this project in the line of reconstructing factory buildings keeping the memory of their industrial past.  Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Werner Huthmacher Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Werner Huthmacher Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Werner Huthmacher Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Lev Chestakov Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Werner Huthmacher Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Werner Huthmacher Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Greg Bannan Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Greg Bannan Reconstruction of the Textile Factory (Tuchfabrik) in Berlin, 2013-2016Copyright: Photograph © Greg BannanWe will not that the proposed solution does not in any way interpret the architecture of the original building, which, on the other hand, is just an plain and ordinary one – rather, it becomes a new facade decoration that obviously raises the class and the value of the building. *** The three projects of reconstructing buildings in Hamburg, showcased at the exhibition, are works by Sergey Tchoban’s Hamburg partner, Elkehard Voss. Grace and elegance The building of Nikolaikontor (Nicholas’ Offices), constructed in 1959 in Hamburg, also completely changed its profile after the reconstruction. A simple striped parallelepiped, “honest”, yet slightly incongruous for its surroundings, widened its plan almost to the point of square, the first floor became higher, slender white supports appeared, and the facade became dominated by a thin light-colored network. Strictly speaking, the building looks nothing like the original, even though it does stay in the paradigm of modern architecture.  The KWK building in Hamburg before the reconstructionCopyright: Provided by Tchoban Voss Architekten Reconstruction of the NKK building in Hamburg. Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Meike Hansen archimagesThe project of reconstructing the building of the “Kaiser Wilhelm Office”, built in the 1950s, was jokingly by the architects as “The Kaiser’s New Clothes”. The building, constructed in the 1950s, was built up with two new floors; two glass panoramic elevators were added commanding the views of the surroundings. The façades with a thin two-tiered natural limestone grating contrast with the adjacent glass building.  The KWK building in Hamburg before the reconstructionCopyright: Provided by Tchoban Voss Architekten Reconstruction of the KWK building in Hamburg. Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Daniel SumesgutnerTurning a Modernist residential building into a tuly modern one The renovation of three apartment buildings on the western outskirts of Hamburg stands out from the general range primarily with a residential function. In addition to changing the imagery of the facades, the project focused on energy efficient thermal insulation. It received the first prize of the 2012 German façade award in the category “Energy-efficient façade renovation”. Two houses out of three became barrier-free, and were adapted for people of limited mobility. In addition, the housing was supplemented with small offices (no more than 4 people in each), and the architects created conditions for the development of a shopping center, dividing the space between houses into open and private zones.  The Schenefelder Holt building in Hamburg before the reconstructionCopyright: Provided by Tchoban Voss Architekten Reconstruction of the Schenefelder Holt building in Hamburg. Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Daniel SumesgutnerFrom a purely visual standpoint, however, the late-modernist slab – still laconic, but already coated with brick, the way it was done in the USSR in the 1980s – turned, again, into a characteristic example of a modern housing project with a bright facade, not devoid of asymmetric agility. Similar examples are quite abundant in Moscow, although they are more likely to be seen in new construction than in reconstruction with the preservation of the structural basis of the house. *** Making it romantic Still another group within this narrative is represented by two St Petersburg constructions by Sergey Tchoban, which, for obvious reasons, must be more familiar to our readers – the business centers “Langenzipen” (2006) and “Benoit” (2006). Interestingly, these are the earliest examples of all. Both reconstructions were initiated by Sergey Tchoban who suggested that the client keep the building’s framework, replacing the facade. Both are designed in silk printing – a method that makes it possible to apply virtually any images on the facades – from photograph of the historical facades decor, like in Lagenzipen, which ultimately fitted in perfectly with the Kamennoostrovsky Avenue  The building of Langenzipen business center in St. Petersburg before the reconstructionCopyright: Provided by Tchoban Voss Architekten The Langenzipen business center. Reconstruction by Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Bernhard Krollto enlarged gouache paintings, like in the “Benoit” business center, whose main facade after the reconstruction became a “permanent exposition” of the works by this artist of Silver Age.  “Russia” factory in St. Petersburg, the building of “Benoit” business center before the reconstructionCopyright: Provided by Tchoban Voss Architekten “Benoit” business center in St. Petersburg. Reconstruction by Tchoban Voss ArchitektenCopyright: Photograph © Aleksey NaroditskyOne can easily notice that for St Petersburg Sergey Tchoban uses a slightly different approach, more on the theatrical and romantic side – probably like his native city, famous, in addition, for the integrity of the historical buildings (it is somehow even embarrassing to mention the status of the cultural capital). The buildings reconstructed by Sergei Tchoban in St. Petersburg acquire completely new properties that do not go back either to themselves or to the history of the industrial zones, of which they were a part before the reconstruction. If the facade of the Berlin textile factory was invented based on its own history, then the meanings here go back to the general context of the city’s culture as a whole. Relatively recently (2018–2020), Sergei Tchoban applied a similar approach, based on an enlarged reproduction of photographs of classical architecture details that form a facade that is both historicized and modern, to renovate the building of Hospital No. 23 in Moscow. This project was not showcased at the exhibition but, in my opinion, can also serve as the development and continuation of the theme. Still another reconstruction project authored by Sergey Tchoban’s SPEECH, headquartered in Moscow, was recently considered by the architectural council of Moscow. *** The exhibition, based on Sergey Tchoban’s German portfolio, presented a very wide range of possible approaches to reconstructing Modernist buildings. We will yet again emphasize here that we are not speaking here about reconstructing some high-profile architectural heritage sites, but about breathing new life into buildings that would otherwise have been destroyed. Most of them – let’s face it – were not characterized by either individual or however attractive artistic solutions – rather, they were examples of what the construction industry could do for purely utilitarian purposes. The options for the completed reconstruction projects combine both the preservation of a solid frame and the addition of ”green”, that is, environmentally responsible, as well as socially responsible options, which is necessary when designing in modern Europe, and the individuality of the image that each building received as a result. We admit that they have evolved from relatively standard projects, which in each case delicately demonstrate their being special. Part of the individual author’s approach was the attention to the specifics of the reconstructed buildings and their surroundings, which made it possible to make decisions in each case, based on the initial data: to preserve its imagery or to replace it with something else. It is interesting that the “fan of solutions” stretches from the delicate preservation of Modernism or the interested development of a modernist ensemble in Berlin of our time – to beautiful “literary” images in St. Petersburg that sprang 15 years ago. All of these are examples of the European approach, which can be viewed as examples of the attitude of the postindustrial society to the constructions of the previous, industrial society – as individual samples, of let’s say, “sanitation of the urban fabric”. |

|