|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 26.12.2018 | |

|

The Temple of Hospitality |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

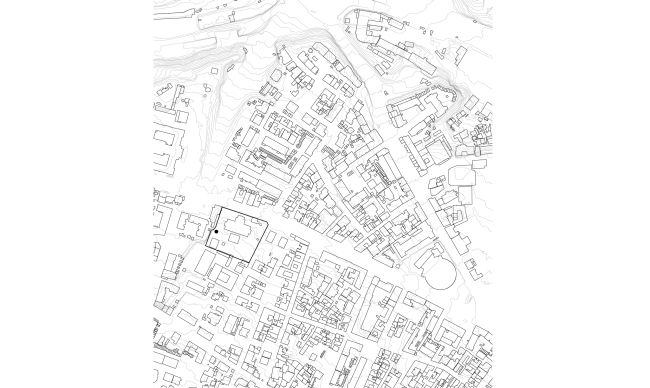

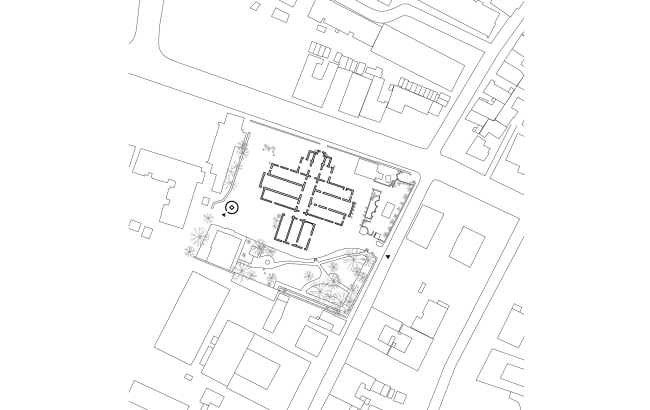

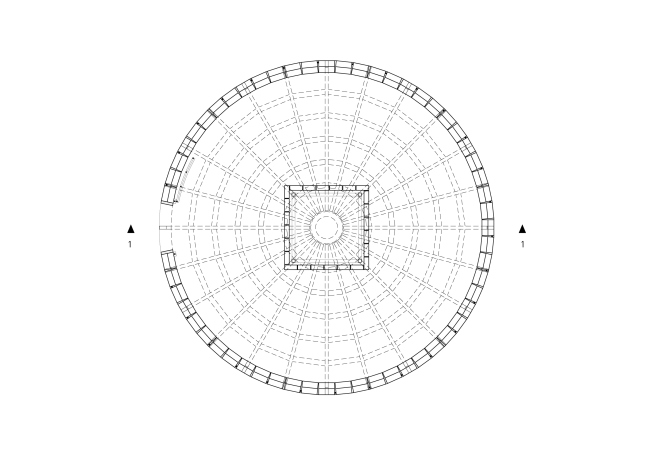

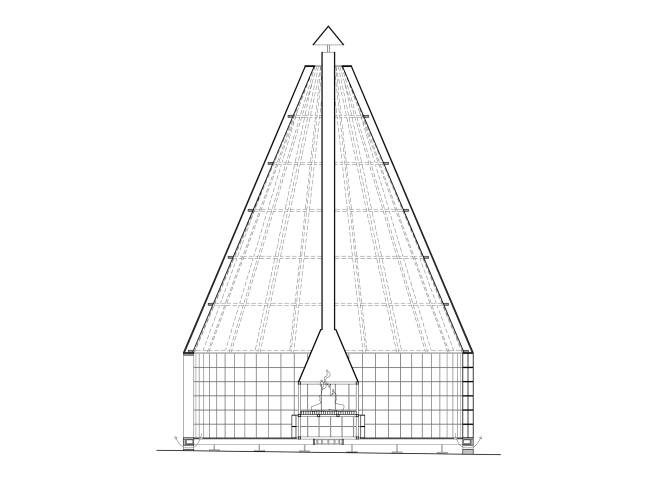

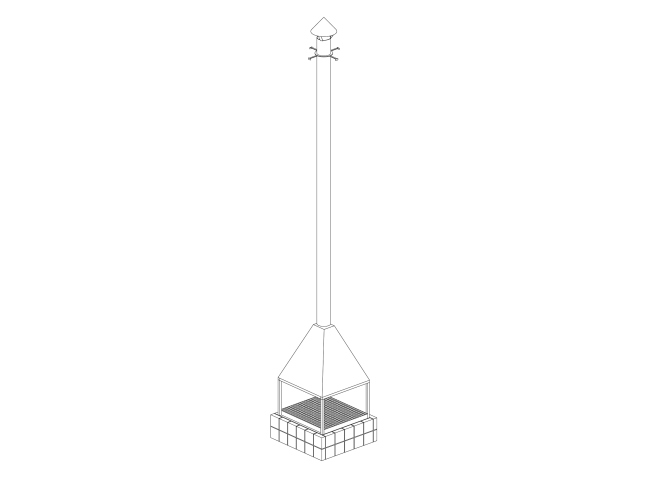

| Studio: | |

|

The pavilion of Chacha Ceremonies at the festival of arts in Tbilisi is almost the quintessence of a few “archetypal” techniques of Alexander Brodsky; and at the same time the Georgian sunshine and wine must have given to it quite a different quality – it looked no longer fragile and brittle but rather as if it was almost made of stone. The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Yury PalminThe pavilion was built for the Tbilisi festival of arts that took place on the territory of the art and gastronomic cluster lying around the city’s first (but now ex) cognac brewery No 1 Saradzhishvili, whose pseudo-Roman was designed and built in 1894-1896 by the architect Alexander Ozerov. The place for the pavilion was found at the foot of the walk leading from the main entrance to the territory belonging to the hotel. The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. Location plan. 2018.The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. Master plan. 2018.As the authors explain, they came up with the idea of this project when they came across a stack of glass blocks in one of Tbilisi’s warehouses, which contained glass of blue, white, and green colors. The six rows of glass blocks form a wall that is about 22 centimeters thick, and is not exactly transparent but still translucent both ways. The wall is arranged in a perfect circle, resting on metallic structures supplied by Metall.works of Aleksey Khrapov, of whom the architects insisted that he be mentioned in this article as a coauthor of this installation. There is yet another metallic hoop in the top part of the wall; up from it begin the wooden structures of the conical roof, crowned at the top with yet another metallic hoop around the hearth chimney. The cone is covered by two layers of tar paper both inside and outside. The height of the glass block wall is 1.5 meters; the height of the cone of the roof is 6.2 meters. The hearth is situated exactly in the middle; also made up of glass blocks, it glows from the inside. Above it, there is an air extraction system and the chimney; everything is made from unevenly rusted metal but still not corten steel. The little hip, which covers on top the end of the chimney from the rain, is totally orange with rust, and, when viewed from a distance, looks like a decorative finial, the head of a decorative little nail that crowns the tip of the roof – yet, at the same time, serves quite a practical purpose. The hearth is surrounded by plastic beer can boxes that serve as stools. At the base of the walls, there is a low-rise band of the concrete foundation that serves as the leveling base for the glass blocks; the concrete band is pierced by numerous round holes that provide end-to-end ventilation of the pavilion by way of the natural upward draught, since its tall cone endures a rather intensive air flow. The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Yury PalminThe pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Olga SaboThe pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. Plan on the floor level. 2018.The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. Section view. 2018.The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. Axonometric drawing of the fireplace. 2018.The pavilion perfectly matches the context of Alexander Brodsky’s creative work, even making one suspect that the author deliberately gathered and accentuated in it the most noticeable and characteristic features and archetypes – as is he was aiming at creating a “Brodsky Archetype”. The walls are made from accidentally found recycled materials belonging to the time of the Soviet postwar modernism, once obsolete and monotonous and now rediscovered again in all the glory of all of its shades and nuances, which the authors lovingly enumerate in the project description (pray the authors will forgive me but back in the day I simply abhorred glass block walls, even the ones in the First Humanitarian Building of the History Department of the Moscow State University; maybe, I was wrong). The same kind of walls made from recycled materials, which is one of the cornerstones of modern art, based on the concept of sustainability, but, more importantly, bringing up a lot of nostalgic memories, is to be seen in other projects, namely: in the pavilion of Vodka Ceremonies from Pirogovo, to which the name of the current installation can be traced – where the windows are essentially painted-over window frames; in the Rotunda from the Archstoyanie Conference – old doors; in the new villa PO-2 (same instance) – a concrete fence. As for the tar paper, it is simply one of Brodsky’s favorite materials today: we can remember the lopsided little house at the Venice Biennale, or the pavilion of the project “101st km Further Elsewhere” designed for the Pushkin House in London. The fireplace is yet another archetype, it is often to be seen in the expo projects of the 2000’s, and in earlier etchings; Brodsky cannot fancy a home without a fireplace, which is fair enough, it must be admitted. The center of the rotunda made from concrete slabs is the hearth. It is situated specifically in the middle, and not in the corner, like you would expect in modern private residence construction. The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Yury PalminMeanwhile, of course, in spite of the obvious recognizability of its constituent parts (which is probably the effect that the authors were deliberately aiming at), which look as if they are saying “repeat actions make perfection”, the pavilion does look different. First of all, Brodsky is very context-sensitive. In the “dacha” settlement of Pirogovo, the prototype of the name of this installation, the pavilion looked like a greenhouse or a veranda, the latter being the traditional place of Moscow suburb imbibing of the pre-1990’s. A much larger, squeaky-wooden Rotunda is closer to the ideas of Palladian manor house architecture. The little houses at the foreign exhibitions looked more like a bum’s makeshift shelter, and neither Pirogovo houses nor these “bum” installations have fireplaces in them. The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Olga SaboThe pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Olga SaboThe pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Olga SaboIn Georgia, the pavilion is solid and even monumental. There is some wood in the dome structure but it is not visible, and, being wrapped in the tar paper, it looks pretty much like concrete. One must note that what this project is missing is one of Brodsky’s favorite themes, namely, that of fragility of these makeshift structures, which seemingly can be traced back to the “quay” restaurant “95% ABV”. Probably it is because here in the south, even a shepherd’s hearth will be most likely made of rocks. Unlike the Moscow and foreign “shacks”, the Georgian pavilion looks like a stone chapel, a temple of Chacha (the famous local grapevine brandy), or, more broadly, like a temple of hospitality. And there is also a lot of sturdiness about that and even the contrast with the pavilion of vodka ceremonies with its proverbial wash-basin. Everything is somehow different here. The pavilion of chacha ceremonies; author: Alexander Brodsky, coauthor: Maria Kremer. 2018. Photograph © Yury PalminIt rather plain to see that the volume looks like the dome of a Georgian temple – in terms of its outline, laconic volumetric geometry, and even the glow of its drum-shaped body. But then again, the same silhouette here can be displayed by the turret on the wall, although yet another prototype comes up, not Georgian at all, yet still functionally close: the so-called Roman Kitchen in Abbaye Royale de Fontevraud, which looks so much like our tent-shape type churches. At this point, surprising though it is, another law comes into force, not all-Georgian but more specific context of the cognac brewery, which looks partially like a Georgian but more like a Roman temple. Together with the pavilion comes the perfect Fontevraud. But then again, one can hardly deny the similarities between various Georgian cuisines, and so on. The important thing is that the hearth is burning, giving warmth, and waiting for the guests. |

|