|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 15.05.2025 | |

|

Greater Altai: A Systemic Development Plan |

|

|

Dmitry Leonov |

|

| Studio: | |

| Genplan Institute of Moscow | |

|

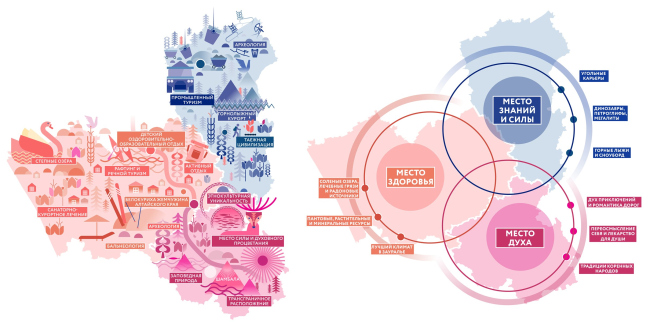

The master plan for tourism development in Greater Altai encompasses three regions: Kuzbass, the Altai Republic, and Altai Krai. It is one of twelve projects developed as part of the large-scale state program bearing the simple name of “Tourism Development”. The project’s slogan reads: “Greater Altai – a place of strength, health, and spirit in the very heart of Siberia”. What are the proposed growth points, and how will the plan help increase the flow of both domestic and international tourists? Read on to find out.

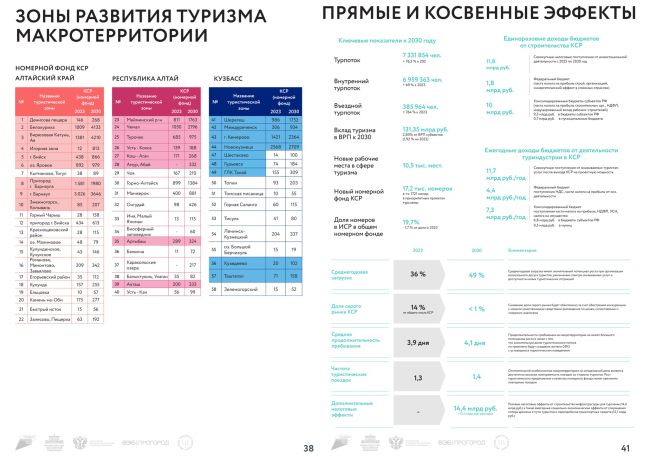

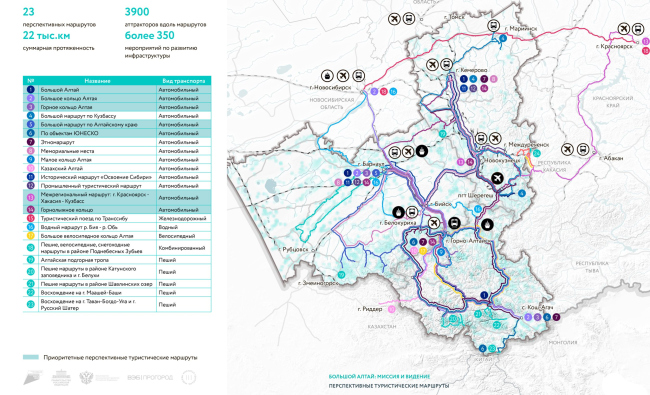

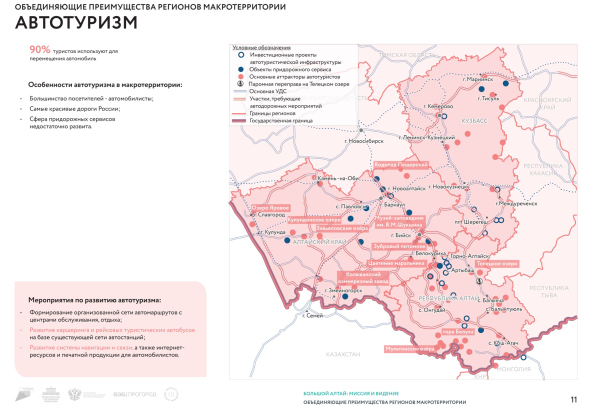

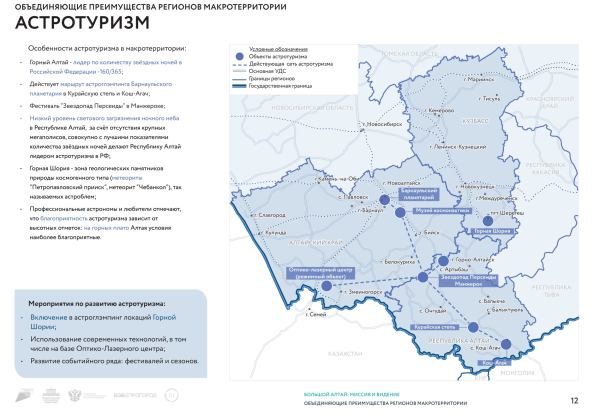

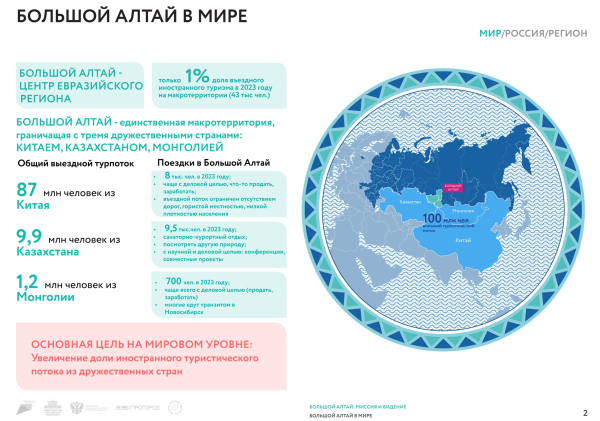

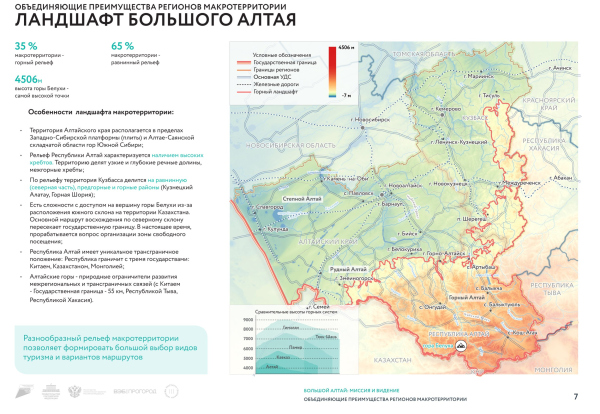

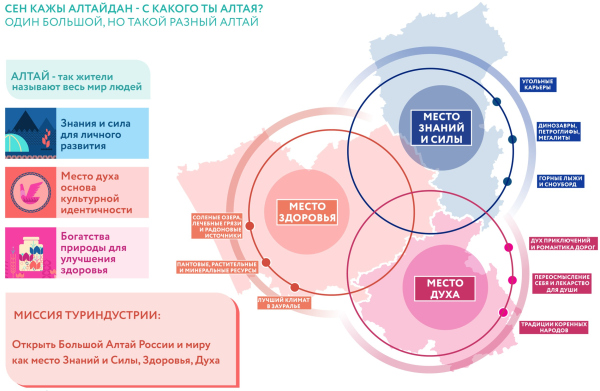

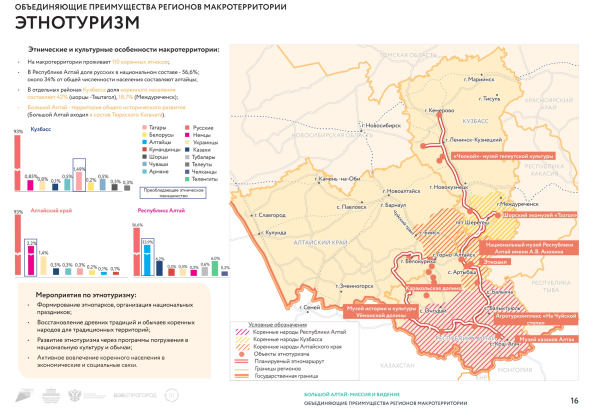

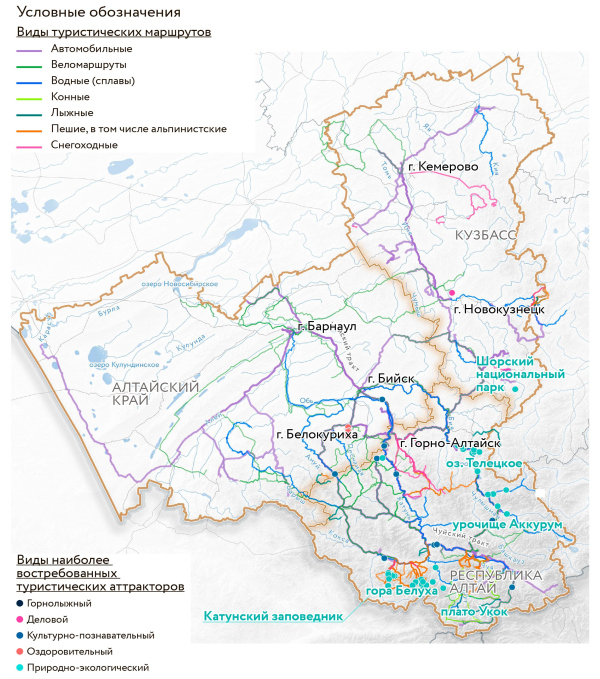

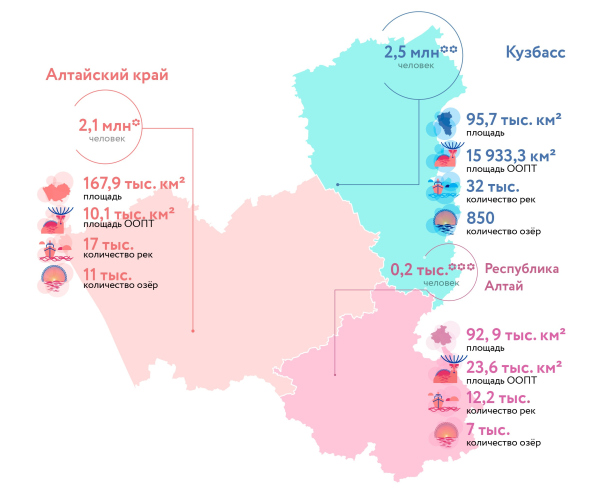

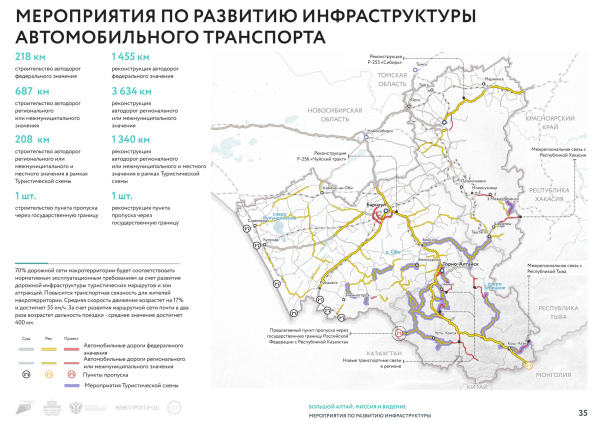

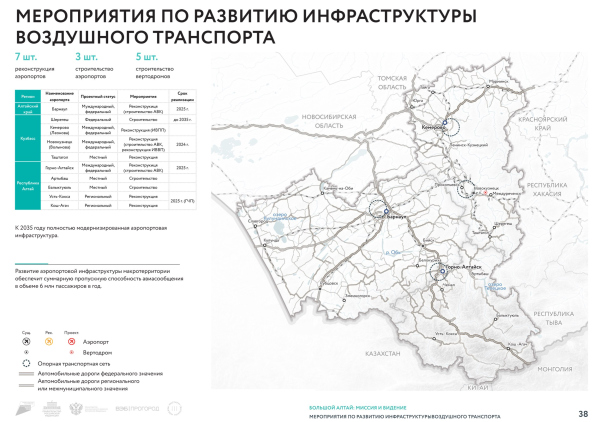

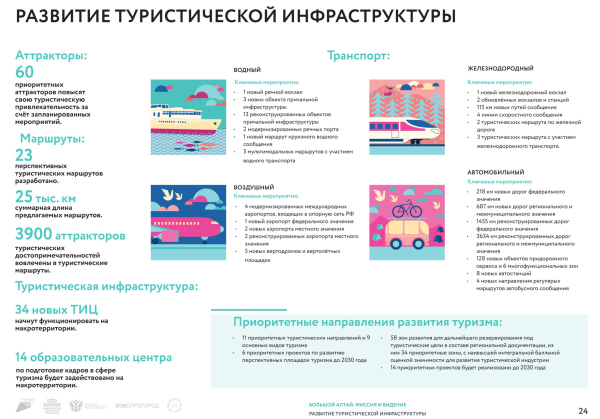

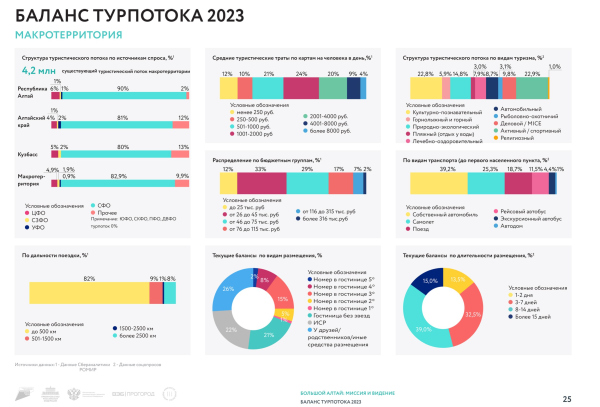

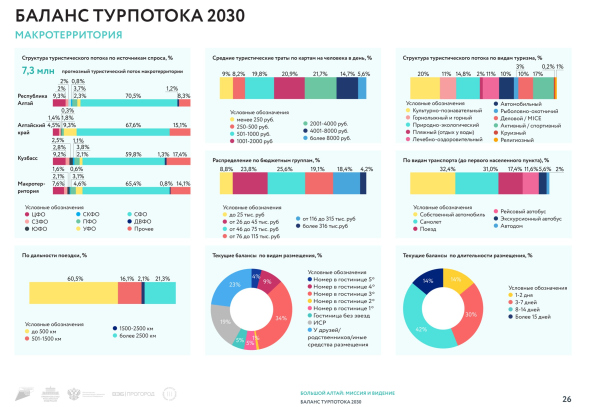

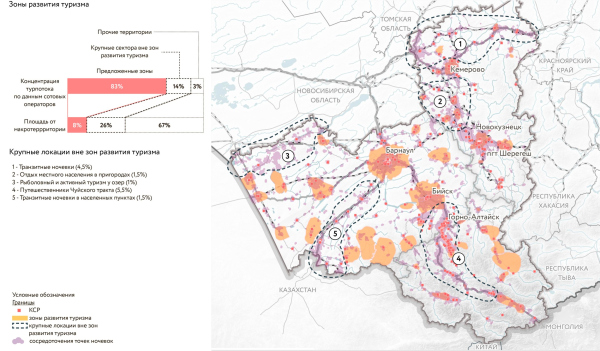

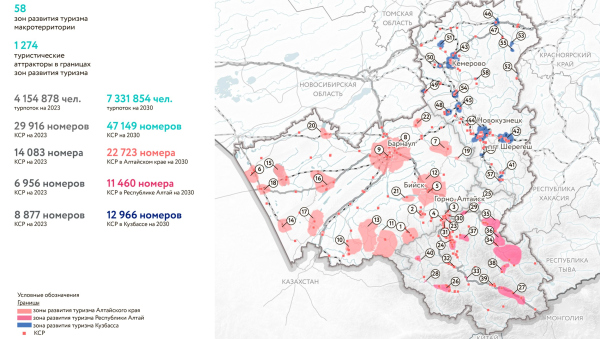

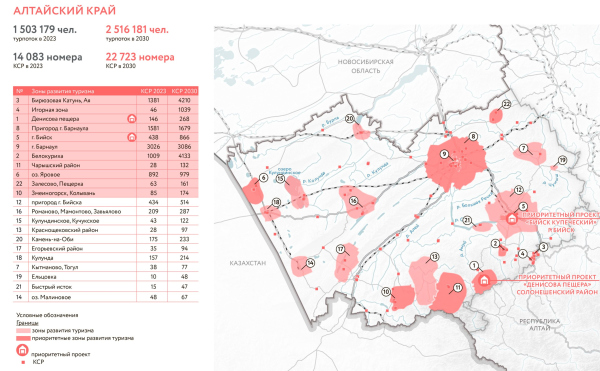

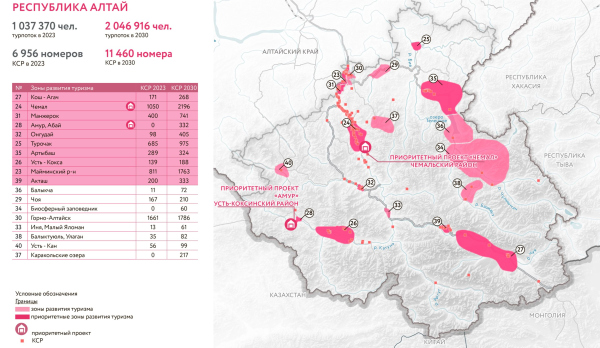

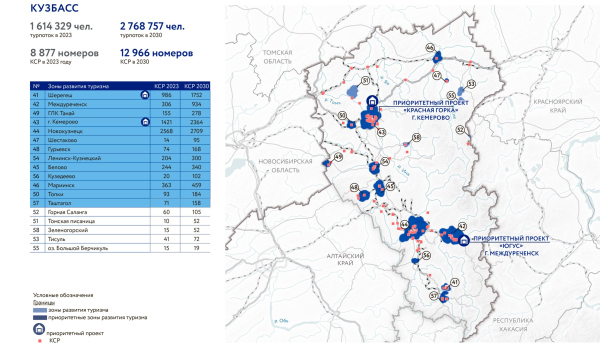

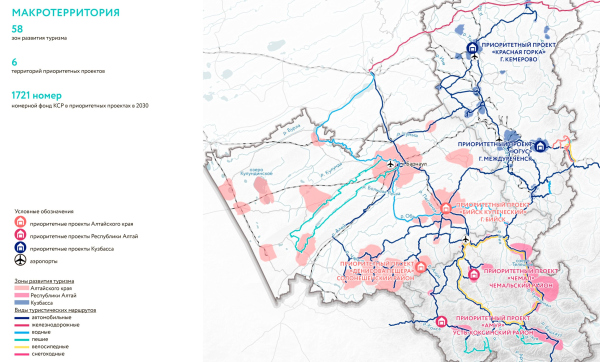

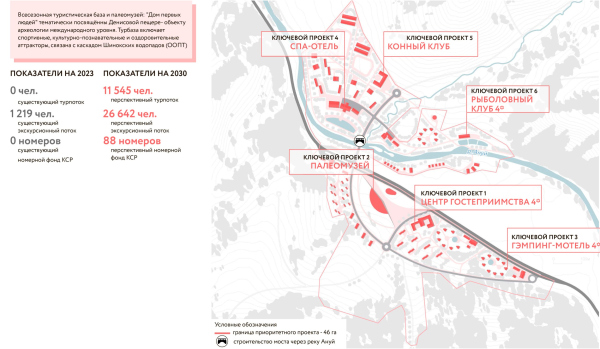

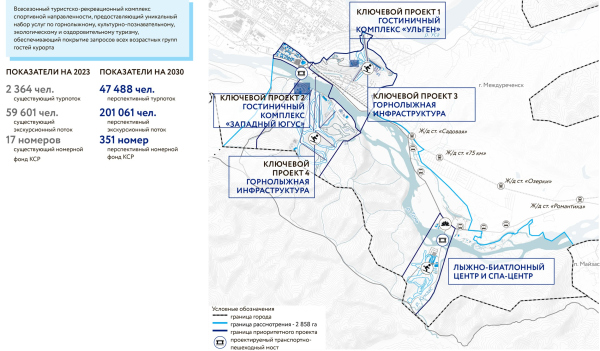

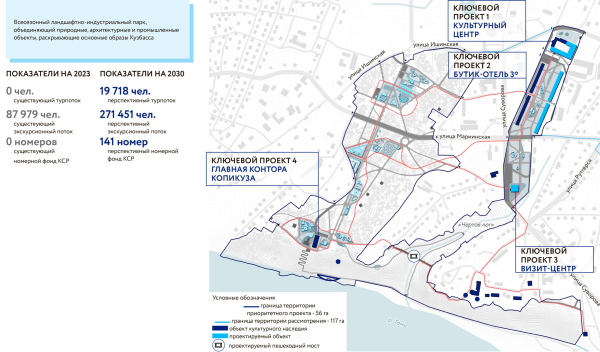

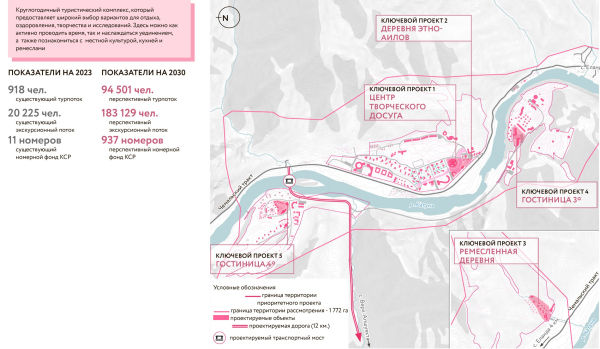

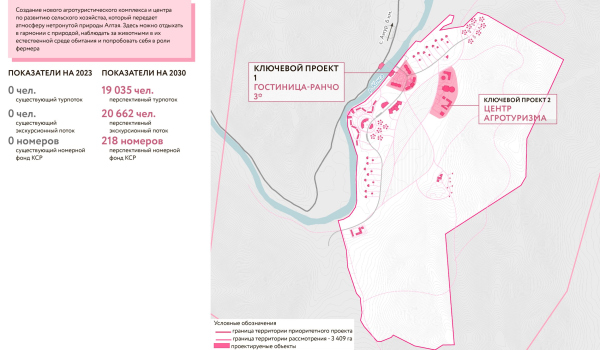

Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupAltai sits somewhere in between – a mix of storyline and geography. The macro-region includes the Altai Republic, also known as Mountainous Altai – the highest mountainous region of Siberia, located in the geographic center of Asia. Mountainous Altai is a tourist destination in its own right, since even those who can barely locate it on a map (and unfortunately, there are many such people even inside Russia, let alone in the rest of the world) tend to associate the name with travel and adventure. The second part of the macro-region is Altai Krai, known for its foothills, healing salt lakes, and health resorts – along with the architectural heritage of 19th-century merchant buildings. The third region is Kuzbass, a coal-mining area whose southern part is home to the Sheregesh ski resort, currently the fastest-growing winter destination in Russia. Across the macro-region, there are 26 ski resorts in total – more than anywhere else in the country. Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupIn other words, the task before the planners was to analyze a very large area – not just a single region but three; to identify commonalities and differences, strengths and weaknesses, and “growth points” with the greatest potential for effective development.  Kseniya Titova, Executive Director of the "VEB Assets: New Solutions" Division, VEB.RF If I were to name the key features of the project, I’d highlight three main components. First, a large-scale analytical effort focused on the spatial distribution of tourism assets across a territory that is currently leading the country in tourism growth and is highly attractive for investment. Second, the delineation of key development zones: our colleagues developed a methodology and a matrix of criteria for assessing how prepared various areas are to receive tourists, particularly in terms of infrastructure. This zoning helps identify where investment in tourism projects is most promising today. Third, the question of positioning – describing new types of tourism products that may be unique to Greater Altai and unlike anything offered in other regions. These are distinctive features that set the area apart from, say, the Urals or the European part of Russia. We at ProGorod (a VEB.RF Group company) oversaw the projects – as a reminder, there were twelve of them – in the role of qualified client. That meant we developed a unified methodology and terms of reference, reviewed deliverables, liaised with the regions, and acted as co-authors of all the project decisions. All of the work was done through interdisciplinary consortia – especially with market consultants in the hospitality sector, since this kind of project requires an in-depth look at the accommodations market. In this case, NF Group served as the lead analyst. We tried not to rely on guesswork, but instead grounded everything in reality – what’s actually needed and what’s actually feasible. We made use of big data and didn’t limit ourselves to official statistics–we worked with everything available. The ROMIR institute handled the sociological research: to identify the tourist profile, they built a representative sample of over 2,000 qualified respondents from across all federal districts using a panel-based methodology. We consider our work on the Greater Altai project a success. The regions were genuinely engaged and incredibly helpful. I want to give special mention to the working group from Biysk – they were deeply involved and proactive. We also received a lot of support from Mezhdurechensk and Kemerovo. In terms of the planning solutions and overall project work, it was an absolute pleasure to collaborate with the team at the Moscow General Planning Institute. They’re a large and experienced group capable of executing projects of this scale with efficiency and skill. Now, about the project itself! It contains a vast amount of data – figures, statistics, and charts. The scope of information collected and analyzed is truly massive. The hotel real estate market was studied by NF Group; the ROMIR institute conducted a sociological survey; mobile operator data came from the Phoenix Lab; transaction data was supplied by SberAnalytics; dozens of in-depth interviews were conducted with tourism professionals in the region (who, as noted by Ksenia Titova, were highly engaged); and, in the early stages, ideas were crowdsourced from local residents. However, perhaps the best description of this research lies in this nutshell: “not just from official sources, but from everywhere”. And, indeed, this is exactly how the future of the Russian regions should be planned – few would disagree with that. The more data, the better. Ideally, you’d want to gather everything.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Tourist Route AnalysisCopyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Project development boundariesCopyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupEven for a major and experienced organization like the Genplan Institute of Moscow, this was a substantial undertaking.  Aleksandr Mordvin, Head of the Urban Development Planning Workshop, Moscow Genplan Institute I’d say that in terms of scope and scale, this project is one of the few of its kind for us. Our Institute carried out a comparable piece of work in the field of tourism for the Caucasian Mineral Waters region. Here, for me personally, as the project lead, it was especially interesting to collaborate with a consortium of professionals and a large number of experts who each contributed their own analytics. We then compiled all this data – sometimes confirming, sometimes disproving our initial assumptions. As part of the project, we developed more than one methodological approach to problem-solving, including methods for calculating tourist flows, prioritizing development zones, and working with extremely large data volumes. Among other things, I’ve never before encountered this level of engagement from the client side – I want to thank Kseniya and her team; they can rightly be called both co-authors and originators of several key ideas in the project. Some of the findings confirmed even the broadest intuitions: yes, the territory shows real promise for tourism development. Taken together, the three regions offer an exceptionally – one might say maximally or even ultimately – diverse range of tourism types: from sports to spirituality, history, archaeology, health resorts, ecology, and even exotic activities like stargazing. The list could go on and on. It’s impossible – and counterproductive – to list absolutely everything. What’s more interesting here is typology. For example, consider this kind of summary from the study: a proposed classification of tourism development strategies for the region. Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupWe spoke with the project authors, focusing on two key aspects. First, the methodologies of the Institute – the approaches that proved useful and were further developed in this project. And second, the innovations they managed to contribute to the existing body of prior work. There’s a certain paradox here – though it’s more apparent than real. One of the Institute’s core methods is identifying and building upon existing work and proposals. Take, for instance, another project by the Genplan Institute of Moscow: the Yauza super-park. Its innovation lay not in designing individual parks, but in uniting them into a single, interconnected and coherent system. This ability to recognize and build on what already exists – rather than ignoring it – is both a strength and, in a sense, an innovation in itself. Because taking full advantage of available resources is, ultimately, a progressive approach. One particularly important method we’ll call the “node principle”. The idea is to study existing infrastructure – say, road networks – and identify points with strong potential that are currently underdeveloped. In this project, those were radial connections: the ability to travel from one attraction to another directly, without detours. “For instance, you can’t comfortably get from Ust-Kan or Ust-Koksa to the Denisova Cave, or from Mezhdurechensk to Sheregesh, or from Tashtagol to Turochak. This results in detours that cause the regions to lose a significant portion of potential tourists, even though they could have extended visitor stays by combining different destinations into a single trip” – the authors explain. “Despite the long travel distances and congestion on the Chuysky Tract, interregional connectivity is still underdeveloped”. Or rather, as project lead Alexander Mordvin clarifies: “The roads do exist – but they’re in such poor condition that only an off-road vehicle can get through”.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupTransport development is also a major topic in itself – especially airports and railroads. From a tourism perspective, these are the primary entry points for visitors from other parts of Russia (except the Siberian Federal District, where most people arrive by car) and for international travelers. Currently, inbound tourism (i.e., international arrivals) accounts for just 1% of the total tourist flow in the macro-region – an extremely small share. The potential sources of foreign tourists are neighboring “friendly” countries: China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan. The authors offer an in-depth nuanced analysis here. China is densely populated in the east and separated from Altai by mountains; however, its population includes a vast number of affluent citizens. Hence, the strategy is to focus on airport reconstruction, destination marketing, and infrastructure improvement. Granting international status to all passenger airports in the macro-region is already part of federal planning. At present, only Kemerovo has an international terminal, but in March this year, the Russian government approved a directive to give the airport in Gorno-Altaysk international status as well. Mongolia is geographically closer, but its population is smaller and less affluent. In this case, the advantage lies in the cultural overlap between the two regions. During the Soviet era, the railway connection between Kazakhstan and Altai played an important social and touristic role, enabling regular visits to relatives and travel to health resorts such as the region’s salt lakes and balneological spas. This activity eventually declined and ceased altogether. Recently, however, an international route connecting the Altai Krai to Kazakhstan has been restored. A key element of the project is the forecast and assessment of tourist flows and accommodation capacity, including the number of hotels and available rooms. What surprised me personally was the presence of precise figures – both current as of 2024 and projected for 2030. The authors emphasize that the master plan’s estimates of tourist trips are based on big data: mobile operator and transaction data were used to analyze the structure and spatial distribution of tourist flows, complemented by information on planned investment projects and other market factors. Their forecasting methodology took into account confirmed plans for hotel and infrastructure development. However, as they explain, they also incorporated hypothetical factors – such as changes in household income, inflation, and whether or not foreign travel will become more or less accessible to an average citizen.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupAnother application of the “nodal” approach is the identification of tourism development zones – entire tourist areas that are either already popular or possess strong potential. A total of 58 such “growth points” have been identified, with six designated as priorities – two in each of the three regions. Individual development concepts have been proposed for each of them.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupFederal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Tourism development zonesCopyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Tourism development zones. Altai RepublicCopyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Tourism development zones. Altai RepublicCopyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Tourism development zones. KuzbassCopyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority projectsCopyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupThe authors place particular emphasis on the project for the city of Biysk. Located at the zero-kilometer mark of the Chuysky Trakt highway, Biysk has preserved its 19th-century merchant architecture. Until now, its historic center had received little attention, and no master plans had been developed for it. In the new master plan, significant attention is given to Biysk’s historic core, including the restoration of several cultural heritage sites, adapted for tourism purposes.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in the city of Biysk: “Merchant Biysk”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in the city of Biysk: “Merchant Biysk”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupAnother key site in Altai Krai is the Denisova Cave. In the 2000s, fossilized remains of a previously unknown extinct human species – Denisovans – were discovered here, and the decoding of their genome earned a Nobel Prize in 2022. The cave may be included on the UNESCO World Heritage List; it’s already been shortlisted. “However, the site itself has yet to reflect the global importance of the discovery made there, even though it has the potential to become a truly remarkable destination – especially in view of the fact that the land belongs to the Belokurikha health resort, which is interested in developing it as an excursion site for its guests” – the authors note.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in the Soloneshensky district: “Denisova Cave”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in the Soloneshensky district: “Denisova Cave”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupMezhdurechensk, located in Kuzbass, is one of the region’s ski destinations. As a reminder, the macro-region has 26 ski resorts – the highest concentration anywhere in Russia. At present, most visitors come from Siberia, with only a small share – less than 10% – from Moscow. The authors propose developing winter sports infrastructure on the slopes of Mount Yugus. This site is not intended to compete with Sheregesh – one of the most popular ski resorts in the country. Instead, Yugus is positioned as a training base for athletes – it already hosts a school for Olympic reserves – and features one of Russia’s best ski jumping complexes, nestled in the unique black coniferous forests of the Shor National Park.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in the city of Mezhdurechensk: “Yugus”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Priority project in the city of Mezhdurechensk: “Yugus”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupA completely different project – yet in some ways akin to Biysk – is being developed in Kemerovo: a theme park dedicated to the history of Kusbass’s industrial development. “It’s a fascinating story – say the authors – Few people know that back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the mine that gave rise to modern Kemerovo employed people from 30 different nationalities, including workers from the U.S. – at one point, job advertisements encouraging people to come work in Kuzbass were even published in The New York Times”.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in Kemerovo: “Krasnaya Gorka”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in Kemerovo: “Krasnaya Gorka”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupTwo more projects are located in the Altai Republic: the Amur agricultural tourism complex on the Koksa River, with 218 guest rooms, and the comprehensive development of tourist infrastructure in Chemal, on both sides of the Katun River. Today, Chemal is the republic’s most popular destination, just an hour and a half’s drive from Gorno-Altaisk Airport. Its popularity has led to chaotic development and “overtourism”, resulting in a loss of identity and the distinctive character of the place.  Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in the Chemal District: “Chemal”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in the Chemal District: “Chemal”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in Ust-Koksinsky District: “Amur”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region. Priority project in Ust-Koksinsky District: “Amur”Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF GroupSpeaking of ecology and ethnography. Across the three regions, the authors counted 110 indigenous ethnic groups. The predominant “ethnic minorities” in the area – yes, that’s actually a valid phrase in this case – are the Altaians and the Shors. There’s also a long-standing German presence: since the 18th century, German specialists in mining and metallurgy have been coming to Altai on contract. In southern Kuzbass and eastern Altai Krai, Old Believers continue to live. As for environmental concerns, the project seeks to address the excessive human impact on natural areas – namely, the uncontrolled flow of tourists and the encroaching development of Altai’s landscapes. Expanding and reorganizing the road network is intended to channel tourism flows more effectively, encouraging predictable visitor behavior and shielding the natural ecosystem from overuse. Honestly, proofreading this makes me want to go to Altai. Salt lakes... prehistoric humans... stargazing... and the mountains, of course. Federal interregional tourism scheme for the spatial and territorial planning of the “Greater Altai” macro-region.Copyright: © Genplan Institute of Moscow / provided by ProGorod, VEB.RF Group |

|