|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 24.12.2024 | |

|

A Paper Clip above the River |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Sergey Kouznetsov | |

| Studio: | |

| Genplan Institute of Moscow | |

|

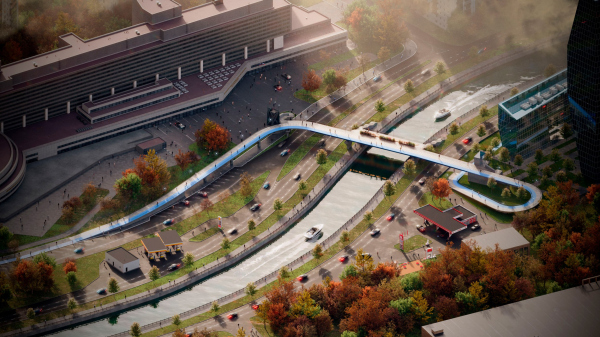

In this article, we talk with Vitaly Lutz from the Genplan Institute of Moscow about the design and unique features of the pedestrian bridge that now links the two banks of the Yauza River in the new cluster of Bauman Moscow State Technical University (MSTU). The bridge’s form and functionality – particularly the inclusion of an amphitheater suspended over the river – were conceived during the planning phase of the territory’s development. Typically, this approach is not standard practice, but the architects advocate for it, referring to this intermediate project phase as the “pre-AGR” stage (AGR stands for Architectural and Urban Planning Approval). Such a practice, they argue, helps define key parameters of future projects and bridge the gap between urban planning and architectural design. The new campus buildings of Bauman MSTU have been a standout of the season; we’ve already covered them, noting at the time how vital and prominent the pedestrian bridge is within the project. NoneThe bridge is visible from the embankments, serving both as a feature of the city panorama and as a viewing platform itself (thanks to the amphitheater integrated into it). The MSTU students cross the bridge constantly – sometimes in large numbers. NoneI checked it out myself, traveling from the dormitories to the main square and back – what a marvel of convenience, despite the significant “scatter” of new and old campus buildings throughout the part of the city. It’s not always the case, but here you can truly feel the bridge acting as a spatial “thread”, weaving the campus together as a cohesive whole. Unsurprisingly, the project won the Moscow Architecture Award in the summer of 2024. The idea of connecting the two parts of the campus with a pedestrian bridge originated with Moskomarkhitektura and Sergey Kuznetsov. The bridge itself was developed by the Advanced Projects Department of the Genplan Institute. Although their focus was on the planning documentation, they went further by proposing the bridge’s distinctive shape – resembling a “paperclip with one leg extended” – and enriching the “linear infrastructure” with the public space of the amphitheater. None , Genplan Institute of Moscow The resulting MSTU bridge can be understood as an example of a concentrated urban planning project. Simply involving even the most talented architect would not have been enough here – an architect by default works within predefined conditions, fitting their ideas into established boundaries. We, however, had the opportunity to adjust the regulatory lines: narrowing and shifting the roadway, altering the boundaries of the natural complex, and relocating utility networks. Architects, in most cases, do not even address such tasks. But it was precisely this synthetic approach that allowed the project to come to life. I would call this stage a “pre-AGR” – of course, it’s not officially recognized in legislation, but something similar was mentioned in the renovation decree: if you recall, architects collaborated with us on drafting the site plan. This not only improves the quality of projects but also saves time and resources in the future, minimizing revisions. We wanted the bridge to become a “cult spot”, a place for meetings and interaction between academic buildings and dormitories, like the fountain at MARHI. But a linear object is always about transit, and calculating the flows. I’m glad the city supported our idea, and we managed to complement the transit function with a public space. We spent a long time discussing the orientation of the amphitheater. It seemed natural to orient it toward the sun, but then the audience would face a view of gas stations. Instead, we oriented the amphitheater northward, offering those seated a sunlit landscape with the crystalline dormitory buildings in the background. NoneThe decision to orient the bridge’s panoramic view northward proves to be the right one: the glass facades of the new dormitories reflect the brick campus buildings opposite, creating scenic “backdrops” for a classic urban landscape. It will be interesting to see if the eternally busy students will hang out here – we were told during our tour that these new buildings house student leaders and high achievers, who are supposed to be constantly studying, spending their time in the library, right? But the very experience of “sitting above the river” is intriguing. It seems, at least in Moscow, that nothing like this has existed before. We love to pause on bridges to gaze at the river, but typically, people don’t linger long – here, they can sit for as long as they like.  , Genplan Institute of Moscow The relationship of the bridge to the river is, on one hand, that of a divider, and on the other, that of a character, a part of the urban exhibition: as one moves across the river, unique views open up. The bridge is dual in terms of movement: the northern part is dynamic, with a bike lane supporting continuous movement, for which ramps are provided on both sides of the bridge; the southern part is calm, pedestrian, offering the possibility to pause and enjoy the view of the river from the amphitheater that slopes down toward the water. Here, students walking from the dormitory or sports building to the academic building can comfortably spend time outdoors. The bridge’s cantilever over the river is striking both during the day, when its metallic caissons reflect the shimmer of the water, and at night, when the bridge is illuminated.  None NoneIt’s quite the visual attraction! For the “Project” stage, the architectural and urban planning approval, and general design work, credit goes to the architects from Podzemproekt. They were responsible for the elegant caissons, the crystalline glass stair towers echoing the form of the dormitories, and the ramp-supporting concrete columns. These columns, square in cross-section and flaring gracefully at the top like abstract flowers, are a minimalist nod to the pillars at Kropotkinskaya Metro Station.  None None None None None None None None NoneThe integration of stairs, elevators, and gently sloped ramps is a key feature of the bridge’s design. This is why it has such long “tails” – they ensure the bridge provides a seamless, barrier-free crossing from one riverbank to the other. While giving a tour of the new MSTU buildings, Sergey Kuznetsov remarked with some frustration that the bike lanes on the bridge are hardly used by cyclists, but they’ve become popular among scooter riders. In fact, the addition of a bike lane is a major advantage. Standing here above the Yauza River, as an avid scooter rider myself, it became clear that when there are many pedestrians and scooters, separate lanes for each are essential.  None NoneSo, now we have a new pedestrian bridge over the Yauza. For the record, a “Yauza bridge” as such is more than just a structure – it’s a symbol, a theme, an image, especially in cinema: a high, arched “humpback” with steps. These bridges put you in the mind of the canals in St. Petersburg, like the Lebyazhya Canal, but more so Venice. Still, there’s something uniquely “Moscow” about their curves. It feels as though these bridges have always been part of the city’s fabric. In reality, they haven’t. Some were built in 1939, others after the war in the 1950s. The last in the sequence was the Tessinsky Bridge near the lane of the same name. The construction of arched pedestrian bridges is tied to Soviet plans to make the Yauza River navigable – a vision that persisted from the adoption of the General Plan in the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s. Some progress was made: increasing the flow of the Yauza’s tributary, the Likhoborka; building a lock; widening the riverbed; and constructing granite embankments up to Sokolniki. It was during this time that all the existing pedestrian bridges were dismantled and replaced with new ones. Before reconstruction, the Yauza's banks were earthen slopes, and the river resembled something like the Vologda – a waterway neither large nor small. Its pedestrian bridges were simple: wooden, low, with supports or at least one structure obstructing the river, like the 1887 . Incidentally, this is how the bridges further upstream – beyond the reach of the granite embankments – remain today, although they’ve transitioned from wood to metal over time. The 2000s marked a new chapter for the Yauza’s pedestrian bridges as they began to attract more attention. The Rostokinsky Bridge in Yauza Sports Park, just off Prospekt Mira, was the city’s first cable-stayed pedestrian bridge, completed in 2006 – before even the Zhivopisny Bridge. The covered pedestrian bridge built in 2022, linking Elektrozavodskaya and Rubtsovo to the complex “Residences of Architects” (so named!) on the riverbank, is a structure of a different scale. It’s broad, heated, but unwelcoming – evoking metro stations and overpasses. Despite its weather protection – a notable benefit in Moscow – it feels like a barrier requiring emotional effort to cross. Functional, ferrying us from one bank to the other, but ultimately an obstacle interrupting the flow of movement. In the case of the MSTU bridge, there’s no sense of it being an obstacle. On the contrary, it strongly conveys a feeling of connection. Perhaps Vitaly Lutz is right when, in response to my question, “But what about shelter from the weather?” he philosophically remarks, “Well, we step outside and walk along the street in almost any weather. So why not walk across the bridge too?” Indeed, an open bridge is perceived more as an integral part of the urban space, directly tied to the street. The gentle slope of the ramps further reinforces this connection – again, based on subjective impressions. The river doesn’t feel like a barrier; it feels like an adventure. It’s part of a new type of urban space that effortlessly situates itself above the water and the embankments. And so, it seems entirely fitting that the bridge incorporates an amphitheater – a hallmark of contemporary urbanism. It both demonstrates and affirms that “sitting down for a chat” can happen anywhere. |

|