|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 17.12.2024 | |

|

Living in the Architecture of Oneís Own Making |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

|

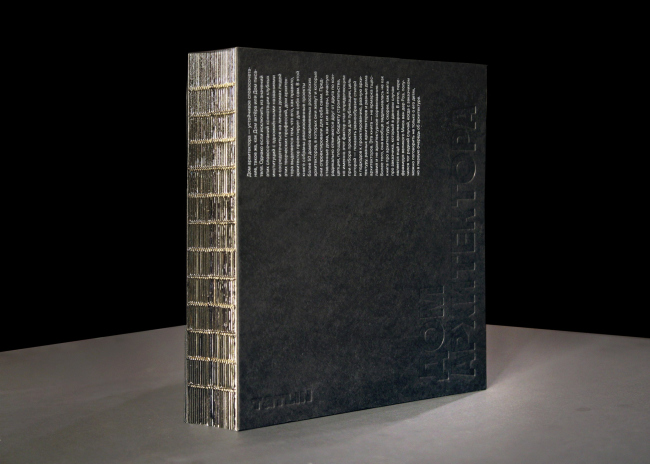

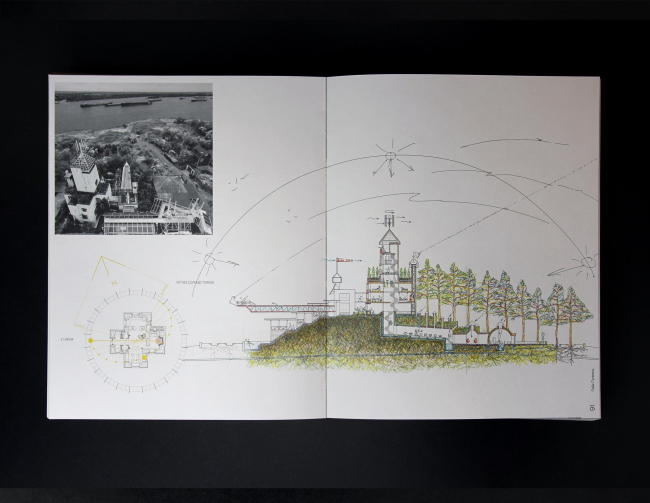

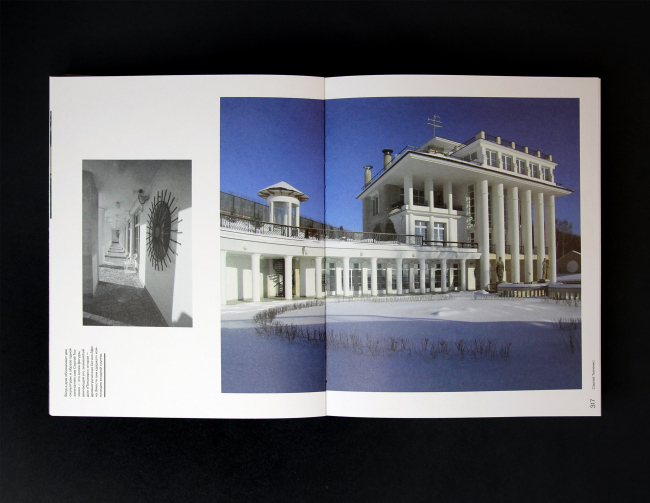

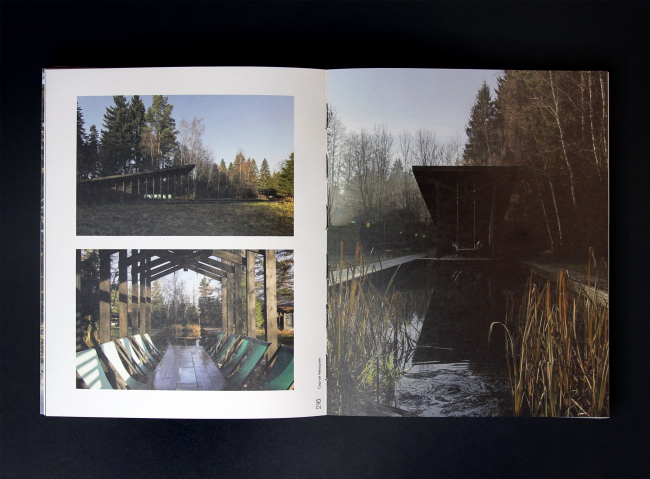

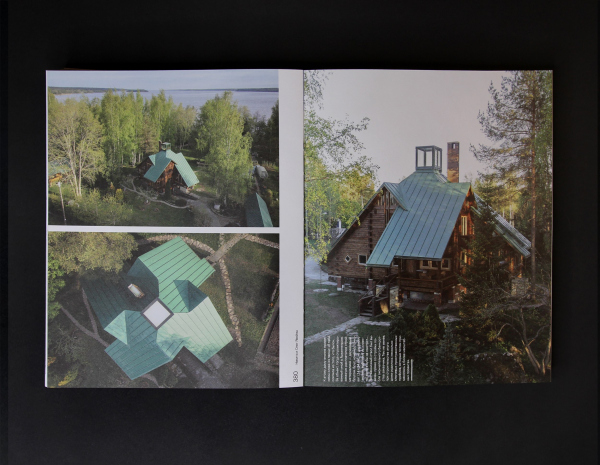

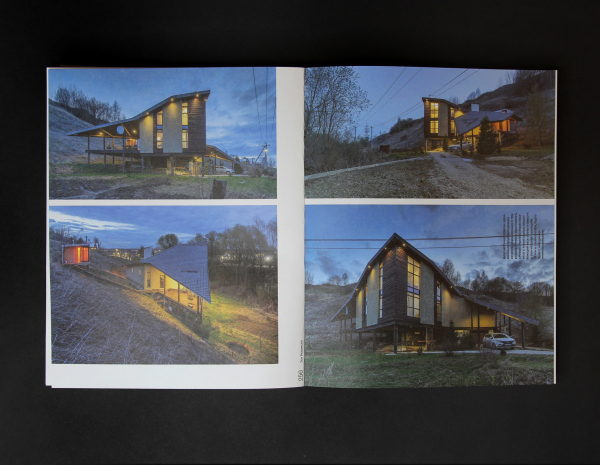

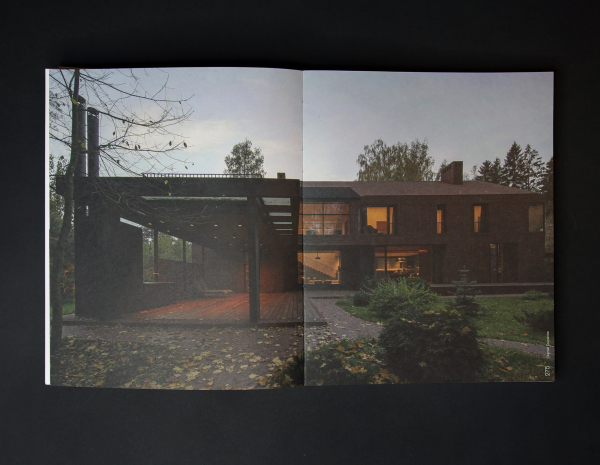

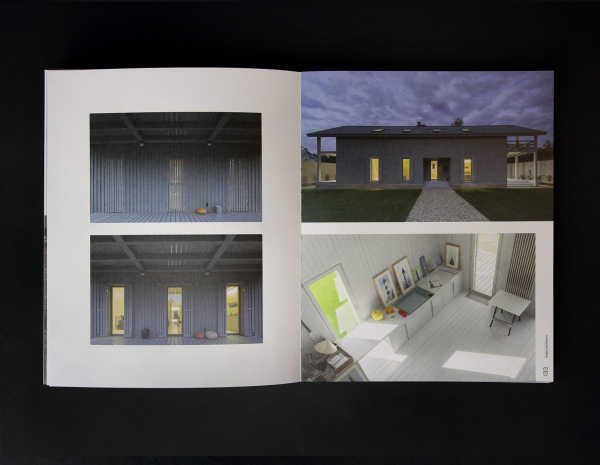

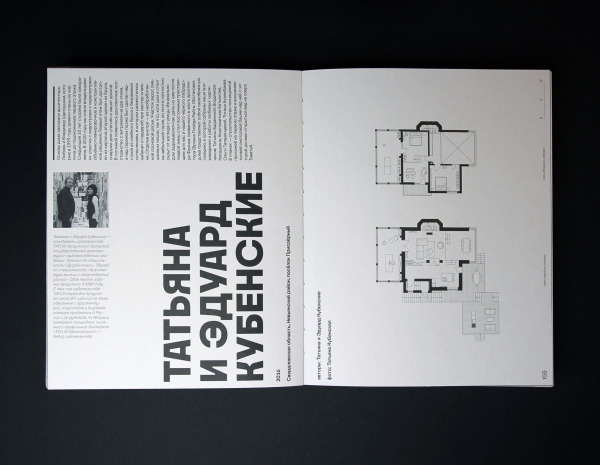

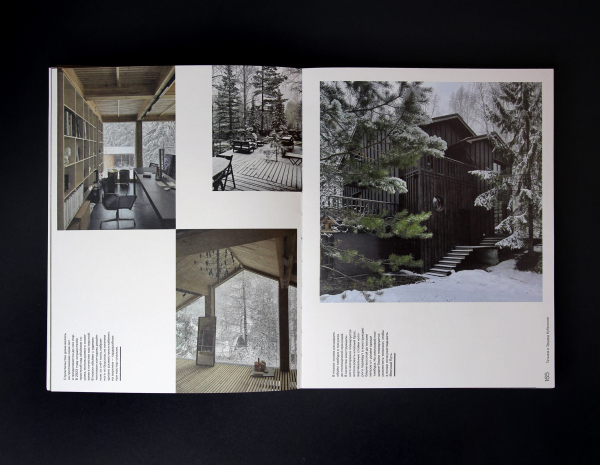

Do architects design houses for themselves? You bet! In this article, we are examining a new book by TATLIN publishing house. This book Ė unprecedented for Russia Ė features 52 private homes designed and built by contemporary architects for themselves. It includes houses that are famous, even iconic, as well as lesser-known ones; large and small, stylish and eccentric. To some extent, the book reflects the history of Russian architecture over the past 30 years. “We wanted to collect a variety of houses, including very famous ones, like Sergey Skuratov’s house, and to uncover lesser-known examples that few people know about” – says Eduard Kubensky, head of TATLIN. The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThe result is undoubtedly worth it. Not only does it cover the entire country, from Moscow to Krasnoyarsk, and a period of at least 30 years starting from the 1990s, but many of the homes are genuinely astonishing. I’m sure I’m not the only one who found two of them particularly striking. The first is Hayk Guliyants’ house in Rostov-on-Don: a gigantic “oddity”, a tower-fortress, a “cross-domed observatory”, where “a twenty-meter tunnel channels air infused with the scent of pine into the house, thanks to geothermal effects”. Sounds strange? Wait, there’s more! The house also boasts a swimming pool atop a long, floating “arrow”. The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThe second is Sergey Tkachenko’s house in the Odintsovo district – a villa-palace in the Roman Baroque tradition, complete with an abundance of massive columns. The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruBut in truth, exploring the book demonstrates that an architect’s personal home can be absolutely anything – even entirely ordinary. However, the nature of the genre is such that the limits of “eccentricity” for these homes are far wider. On their own plot of land, architects have the freedom to “show off” as they please. But then there’s their family, which may have its own opinions about the house. Comfort and coziness are not always sacrificed for the sake of experimentation, and the challenge becomes proving to oneself that their vision is the best – or facing disappointment. It’s intriguing to wonder how many architects, after building and living in their homes, concluded that their design was wrong? And how many would admit it? This is a rich theme for future research. On the other hand, humans are known to adapt to almost anything – so the scenario of “put an architect in a home they designed” can never be a pure experiment. Finally, the architect controls the budget for their own home! In short, the dichotomy where the client of the house is simultaneously its author offers many different perspectives. The study of architects’ personal homes is, of course, not a new topic – it’s been around for ages. There are articles in magazines, reviews, and even compilations, such as ” by Artem Dezhurko. Since at least the 1970s, English-language books featuring collections of architects’ own homes have been published, starting with and extending to works like by Taschen, a longstanding leader in producing comprehensive collections. Such books are often reprinted multiple times. While this theme is well explored internationally, it remains largely untapped in Russia. According to TATLIN, this is the first such book here. I tried to verify this claim and, indeed, it appears to be true.  The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThat said, the preface, written by Asya Zolnikova, delves into the modernist classics of architect-designed homes. It’s both appropriate and engaging, short yet lively and even sparkling, with personal insights into the life of Le Corbusier. The book itself, in contrast, is methodical: Eduard Kubensky states that it features “about 50” homes – half the number in Taschen’s collection – organized strictly alphabetically. Each house is allocated several pages, with the first spread containing essential details and the rest dedicated to large-scale illustrations. The authors refrain from classifying the material into categories, sticking instead to a straightforward compilation approach, which seems fitting for a first-of-its-kind book. Classification, then, is left to the reader. And maybe that’s more fun. The longer you examine it, the more you become convinced that the initial impression – that architects’ homes are more diverse than most – is indeed accurate. Yet certain trends emerge: in the 1990s and 2000s, large, sometimes very large, houses were popular. By the 2010s and 2020s, smaller, more intimate homes deeply integrated into their surroundings became more common. There’s also a noticeable tendency for quirky designs to belong to earlier periods, coinciding with the heyday of such experimental architecture. And, by the way, it’s a shame, dear architects, that you’ve abandoned your quirks – who else will surprise us but you? Someone might counter that Totan Kuzembaev built his tilted house in Lidy, or Evgeny Spirin his micro-tower, both relatively recently. And yet, there’s an undeniable sense of strictness prevailing in today’s architecture. Everyone wants to be stylish. Many succeed, but with that comes a level of solution unification, where – yes, everything looks good, everything is “just right,” but! You’re an architect, aren’t you? Where’s the rebellion? However, sometimes, to spot that “rebellion”, you just need to look a little harder. For instance, Sergey Nikeshkin’s house is deeply immersed in the landscape, almost like Brodsky’s park in Veretyevo... One can’t help but want to see it with their own eyes, to make sure it’s truly as it appears, not just a lyrical photo effect. The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruBut let’s allow readers to explore this marvelous encyclopedia of architects’ own homes on their own. To discover who lives in a house designed by their great-grandfather, or – who designed the house for whom, as some cases go; though mostly the authorship remains with the owners. By the way! There’s a feeling that TATLIN timed the release of this book with the completion of the Kubensky family’s own home: both Eduard and Tatiana, the founders of the publishing house, are architects.  The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru The book "The Architectís House". Yekaterinburg, Tatlin, 2024Copyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruAnd if the actual information about the homes is distributed calmly and predictably, the design, created by Tatiana Kubenskaya, disturbs the reader’s peace without any unnecessary commentary or categorization. It’s a characteristic example of the creative design of our time. With exposed stitching of the strips, meaning it has no spine – this book, I must say, resembles a somewhat related publication, “The Modern Russian Wooden House” by Nikolai Malinin from 2020. However, our book is also black, just like some of the houses inside it; strangely, not all of them... Why the black color? Is it something they love? Or is it just that black is known to be a good heat retainer? But the main design feature is that the book has to be constantly rotated, and it’s quite heavy. For a tired person, that’s an extra effort. One won’t be able to chill and leisurely absorb the information about architects’ homes. It’s hard to say if that’s right. Maybe the need to turn the book is like a low door frame in a peasant’s house: please, bow to the host! Or maybe there is a simpler explanation: architects love to look at pictures and don’t plan on making the texts easy to read. Too bad! |

|