|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 23.04.2024 | |

|

The Paradox of the Temporary |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Studio: | |

| WOWHAUS | |

|

The concept of the Russian pavilion for EXPO 2025 in Osaka, proposed by the Wowhaus architects, is the last of the six projects we gathered from the 2022 competition. It is again worth noting that the results of this competition were not finalized due to the cancellation of Russia’s participation in World Expo 2025. It should be mentioned that Wowhaus created three versions for this competition, but only one is being presented, and it can’t be said that this version is thoroughly developed – rather, it is done in the spirit of a “student assignment”. Nevertheless, the project is interesting in its paradoxical nature: the architects emphasized the temporary character of the pavilion, and in its bubble-like forms sought to reflect the paradoxes of space and time.

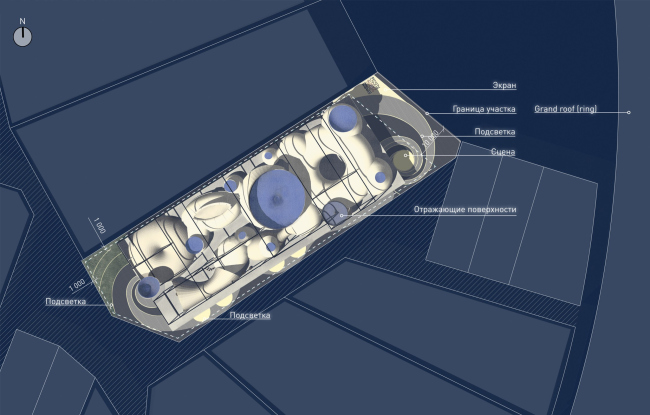

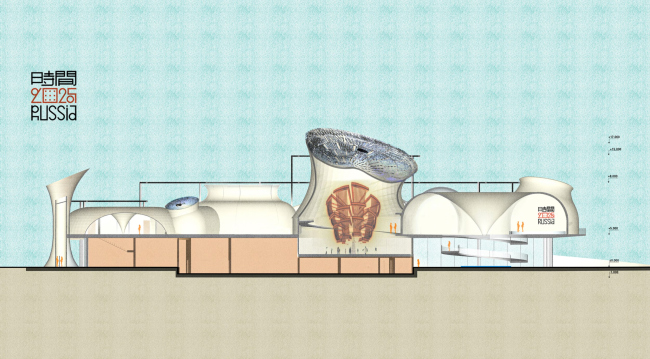

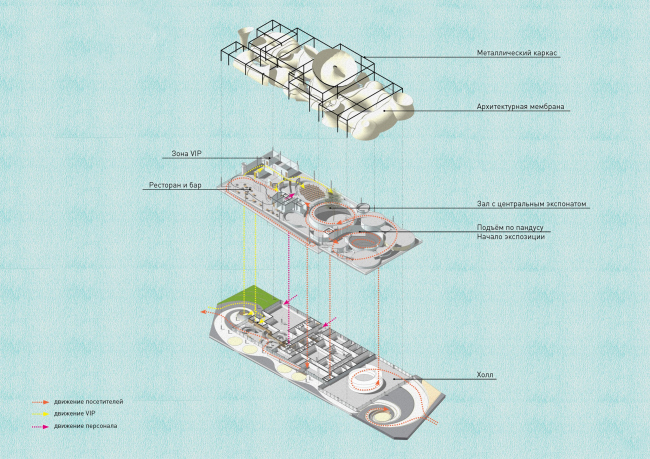

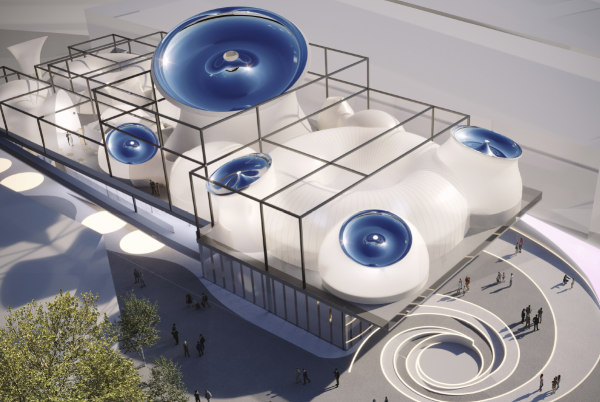

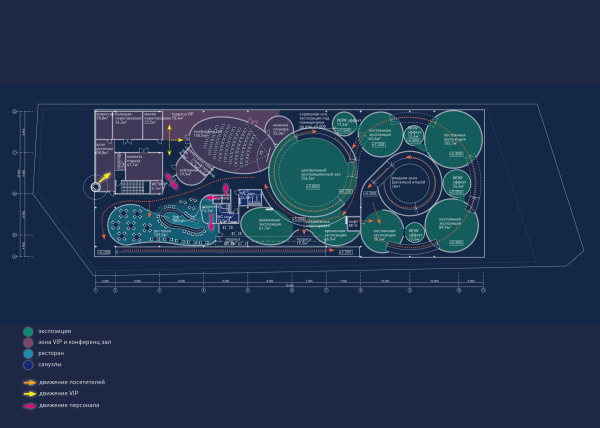

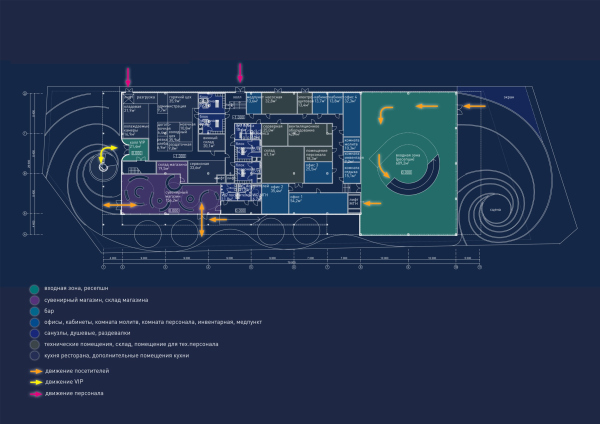

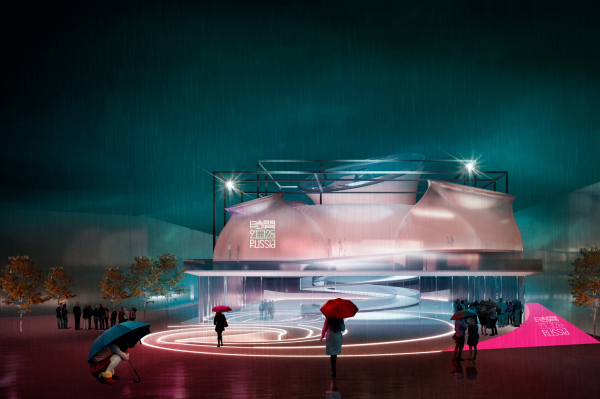

“The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUS “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUSThe pavilion’s shape is quite complex; it resembles an enlarged colony of some microfungi bred in an “aquarium” made of a metal frame that defines its contours a hundredfold. Some elements are larger, some smaller, some have blue “caps” made of, as stated in the project’s description, light-reflecting material. Looking at this weird conglomerate, you think that it could be anything: each volume could grow or lean in any direction, curl up or unfold its “collar” at the top. Meanwhile, there is a certain logic in the arrangement of these volumes – the lower tier is solid, and in the upper tier, which actually dictates the grouping of volumes, halls of permanent and temporary exhibitions are divided into domes of various sizes. The master plan. “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUS“The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in Osaka. A section viewCopyright: © WOWHAUS Plan of the 2 floor. “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUS Plan of the 1 floor. “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUSThe route is laid out along a continuous line of one ramp: it spirals and unwinds, rising from one level to another. The explosion diagram. “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUSUpon entering, according to the description, the visitor enters a “hyper-transition point”. “Time transforms, stretches, and distorts, reflecting in the geometry of the external and internal space” the explanatory note says. And here we move from optional temporality to the realm of another narrative: the architects did not limit themselves to self-irony, and the form of the pavilion should be understood as an image of time – in a futuristic key, based on paradoxes, the visual representation of which we are accustomed to encountering in science fiction films. What we are seeing here are a kind of bubbles of time, into which the visitors would be invited to enter through the “hyper-transition portal” and then wander through paradoxes, where – and here I am indulging into a fantasy, but the material is highly conducive to it – space could contract and expand, or droplets focusing from the domes, or other amazing properties of space would visualize paradoxes of time for the visitor. The entrance area with a pool. “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUS“All other places are very much not strange. There must be at least one very strange place” © The facades made of architectural membrane, according to the brief, were also planned to be of the “media” kind, but through projection mapping instead of LED backlighting. Two types of options are proposed: from paintings of the avant-garde period and from the ornaments of the Cathedral of the Intercession on the Moat, also known as Moscow’s St. Basil’s Cathedral.  The main facade with mapping projections. “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUS “The Most Temporary Pavilion” at World Expo in OsakaCopyright: © WOWHAUSIt never ceases to amaze me how different EXPO pavilions of various years echo each other: if we look at the main façade with ornamental mapping, then “The Most Temporary” (with adjustments for the bulging shapes and changing patterns, of course) may remind us of the Russian pavilion at the 2010 World Expo, designed by the TOTEMENT/PAPER architects. Remember the pavilion that boasted towers with ornaments? It is still there in Shanghai, and you can still see it. But here in Japan, the volumes resemble porcelain cups; they are somehow noticeably Japanese despite the Russian ornaments. Because of the tilt in both directions, they seem to sway: either cups or heads of porcelain dolls, Chinese (well, Japanese, in this case) bobbleheads. In short, a certain Japanese note, which, I dare say, almost all of the contestants sought to bring into their projects of EXPO pavilions, is felt here too. The architects unfold the ideas of “The Most Temporary” pavilion into three component parts: the futurism of the 1920s, Krutikov’s Flying City, Malevich’s Aerograd; time as a category not defined by anything in physics (and here we learn that the Big Bang occurred 13.7 billion years ago); dematerialization or “emersion” – we’ll have to take note of the concept – as one of the trends in modern architecture and construction. Curiously enough, it’s easy to notice that all three declared themes have nothing in common with either the competition brief or the sub-themes of EXPO 2025. This is neither good nor bad – everyone creates as they can and want, what matters is the result – it’s curious, actually, that the same inputs receive different interpretations from different teams. In short, time can evolve in any way and lead to anything. And how one wants to puncture it in some “secret” spot and find oneself in a better future. |

|