|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 20.06.2023 | |

|

Ivan Grekov: “A client that wants to make a building that is “about architecture” is a big value and big luck” |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

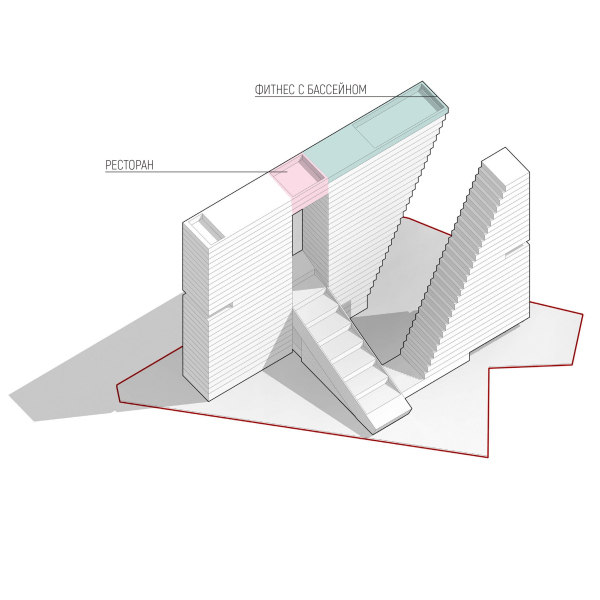

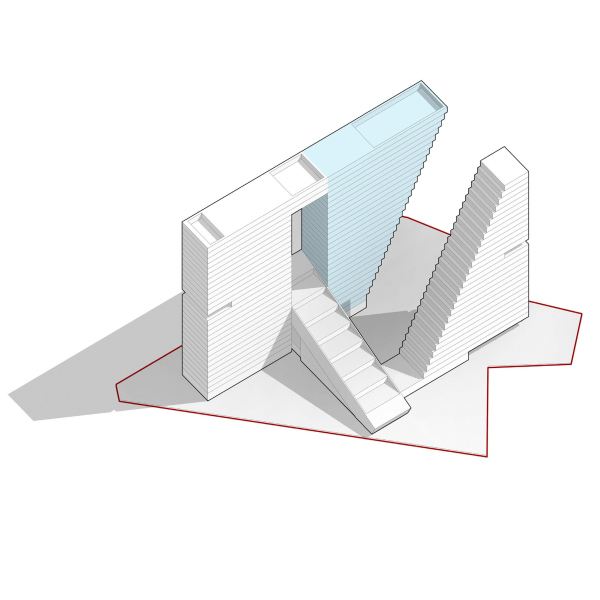

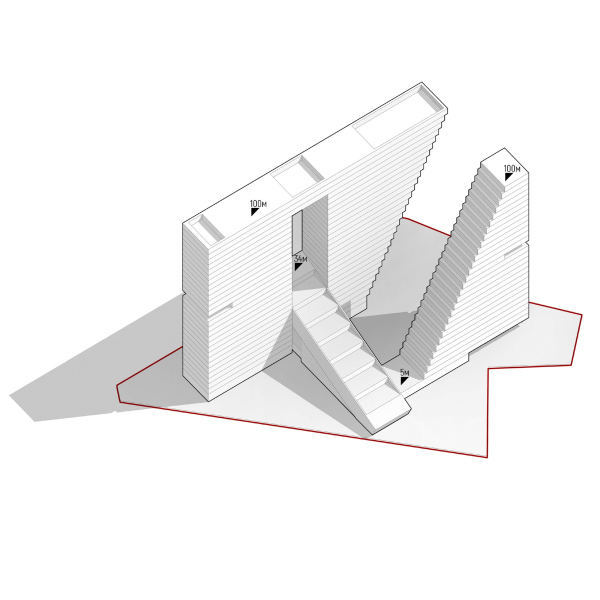

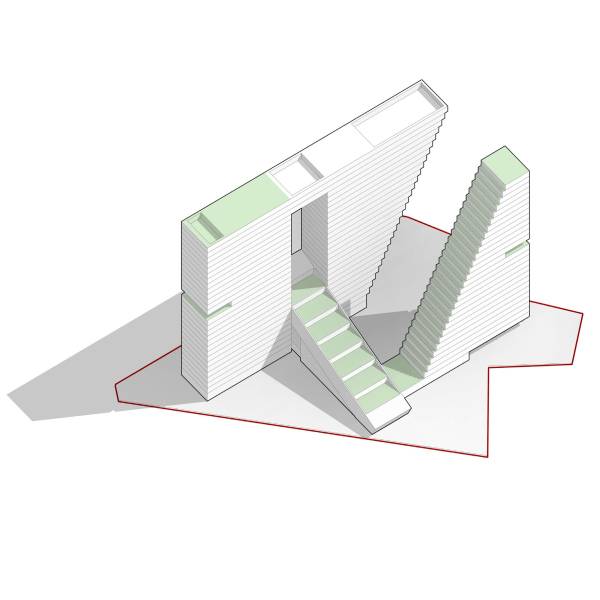

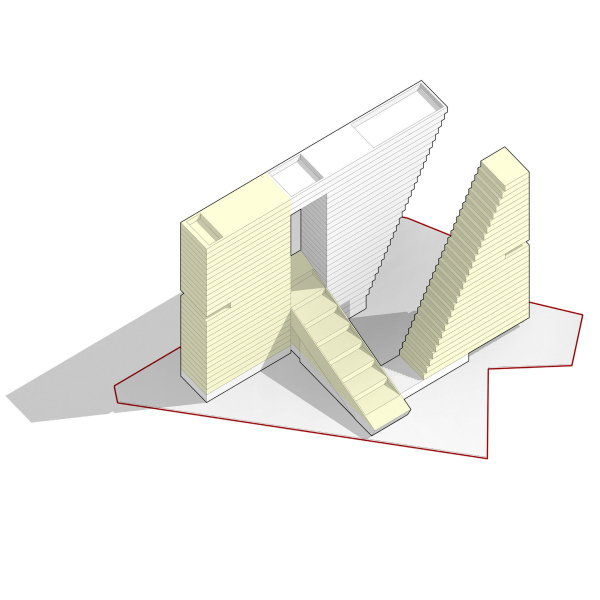

| Studio: | |

|

In this article, we are talking to Ivan Grekov, the leader of the architectural company KAMEN (translates as “stone”), the author of many high-profile projects that have been built in Moscow in the recent years, about the history of his company, about different approaches to form making, about different meanings of volume and facade, and about “layers” in working with the environment – at the example of two projects by Osnova Group. These are the MIRAPOLIS complex on the Mira Avenue in Rostokino, whose construction began at the end of last year, and the multifunctional complex in the 2nd Silikatny Proezd on the Zvenigorodsky Highway; recently, it received all the required approvals. Archi.ru Ivan Grekov, KAMENCopyright: Photograph © Pavel Khomenko / provided by Osnova GroupOur hopes were justified – first, in both cases the client opted for the version that we considered the best, and, second, the projects are developing in the right direction, and virtually without any changes made to the core idea (a few minor things aside). For us, it’s really a breakthrough. Very often a beautiful idea gets horrendously simplified during the actual implementation. Luckily, this is not our case! Yes, the shapes that you create are always very impressive. How do you come up with them? Are they function-based? The volume is positioned quite successfully – it organizes the yard environment without any unwanted extra surfaces; it is terminally effective. I call this approach “architectural origami”: this is a stereometric task – you need to create a three-dimensional structure. This is like a sewing pattern where you cannot take away or add anything – nothing is left to chance. We value such an approach very much because many of our projects have to do with the physical properties and with searching for the right form with regard to some tectonic peculiarities, natural environment, and expected functions. Ivan Grekov, KAMENCopyright: Photograph © Pavel Khomenko / provided by Osnova GroupWhat do you mean when your projects have to do with “physical properties”? As for physical properties, it is the interaction that matters – the way the facade or even the whole building reacts to a sunrise or sunset, to sunny or overcast weather. What makes a sculpture different from a building, what is the first thing that comes to mind? The windows! You look at something, see windows, and your brain tells you – this is a building. What if there are no windows? Some kind of mystery appears! What is this? Some kind of urban megalith! We have one large-scale project on the bank of the Moskva River, where we managed to make a facade, which, if you defocus your vision, starts disappearing and reflecting the environment. There are “architectural narratives” about volumes, about “sculptural-ness”, and about proportions. There is also a narrative about organizing the functions. And there is also a task to create some connection to the environment, with shadows, abr and with reflections. We also call this physics. Ivan Grekov, KAMENCopyright: Photograph © Pavel Khomenko / provided by Osnova GroupWhat does the environment mean to you? Environment is a volumetric notion to us, and we dissect it into layers. There are layers of perception: close vantage points, remote vantage points, and so on. You also need to know how you interact with the building if you are in motion. The next layer is the atmosphere, the air around the building. Essentially, the building connects the earth and the air, and our projects are like transistors that endure this connection. We see our missing in creating the environment on the earth level; then the next level up includes beacons that hover up high and react to the sky and the clouds. If we are to speak about the Rostokino project, the MIRAPOLIS complex, the dialog unfolds inside the complex. There is a highly saturated transport infrastructure around it: public roads, highways, and pedestrian walks too. Inside, the buildings stand rather densely, and the dialogue takes place between the volumes inside the complex.  MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN Architects MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN Architects MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova GroupIf we are to speak about the 2nd Silikatny – here we rather designed “a thing in itself” because the development around it is still in the making; we decided to invent some sort of an “inner dialogue” – in a broad sense, we perceive it as a welcoming element of the Big City. Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova GroupCan these projects of yours thus be interpreted as examples of a “vertical city” or “poly-centers”, like self-contained multifunctional complexes? Yes, you can totally call them that! In both cases, we combine apartments with a highly developed office function and diverse public infrastructure. MIRAPOLIS is a vivid example of how a project can create a self-contained environment inside of it, at the same time harmoniously integrating itself in the life of the city around it. What do I mean? There is a prominent perimeter that performs a sophisticated public function: a shopping mall, a fitness center, cafes and restaurants… We also have a children’s center, a few stores, a food court, and a covered “street” passage inside. Catering for both outside front and the city, all of this activates various spaces, and makes the most of the transport infrastructure as well. On the other hand, we do have a stylobate there – it provides protection for the future residents and ensures a comfortable environment on the inside. In a sense, it is a “fortress wall” that protects you from the noise outside and from unwanted visitors. On the inside, we get a comfortable space for the residents, a private protected yard, and a park. The infrastructure in MIRAPOLIS occupies 20,000 square meters, which is about 10% of the total useful space.  MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN Architects MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova GroupThe vertical character of the city manifests itself in the functional layers of this project. The first layer is the pure public city function. Then we have a mix of the office and residential functions, which develops vertically as the floors grow higher, and is mixed evenly in one of the towers. Plus we are using the roofs of the stylobate and the terraces up high. Yes, MIRAPOLIS is situated not exactly in the city center, but it is itself a center in its own right, so it totally meets the concept of a polycentric city. MIRAPOLIS housing complexCopyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova GroupI’ve heard that you’ve been actively working with the client to finalize the project on Mira Avenue. What has changed in relation to the original bid? The process of the post-competition life of your project is always very eventful, and there is nothing wrong with that. When you get down to practical implementation, you need to consider a whole number of factors and requirements: your apartment range may change, or the key commercial tenants may come with his requirements… The bigger the project, the more changes. At the architectural competition for this project, we offered Osnova Group 12 versions of this project, and the buildings were higher – the exceeded the 120-meter limit. There were two public streets running across our yard, and the towers were interpreted as situated in the “thaw patches” of the stylobate. The city life went on down below, and the inner life of the complex began a little bit higher up; the yards were accessed from the second floor. Meanwhile, the key points of the concept did remain. I cannot say that any radical changes were made to the project. What is your approach to facade design? In MIRAPOLIS, I see sculptural prisms in the piers, you know, of such “bristling” kind, and there are brick pylons in Silikatny… Yes, in the Rostokino project, we explored the “imprint” idea: sometimes you see relief protrusions, and sometimes you see indents of the same shape. In addition, as you go higher, this opposition becomes less acute, as if honed down by the wind, but, yes, down below they are indeed “bristling”. We divided each tower into four such parts to make them look more slender. As for the 2nd Silikatny, we do not even consider the facades to be the main part of the project – quite the opposite, we try to design it in such a way that either details or materials would not become the key part of the architectural solution. You know that many things may happen over the life of the project, the economic situation may change, and so on, and we see plenty of examples when something got in the way, the facades were not constructed the way they should have been – and the project was ruined. This is why we work on our projects in such a way as to ensure that their shell is not their main part; preferably, it should not influence the main architectural statement at all. The building is a sculpture, and the facade is like clothing – it should not affect the architectural statement too much.  Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova Group Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN Architects Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN Architects Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN Architects Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN Architects Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN Architects Concept of developing the land st 2nd Silikatny Proezd, 8Copyright: © KAMEN / provided by Osnova GroupBut then again, in this specific case we don’t have any doubt that the client will ensure high-quality implementation of the project. Your portfolio includes a large number of high-rise projects – how many, by the way? They are all at different stages of competition, so I cannot give you an exact figure. There are also projects of master plans that already include a large number of high-rise dominants. Do you still take on small-scale projects? Yes, we still love working with small-scale projects – we have countryside villas and residences that we mostly do for our intellectual environment, they are by no means commercial. However, they do help us to continue a certain creative search. Our company was founded by my father, Vadim Grekov, back in 1993. Hitherto, he had been involved in some countryside construction. Today, we work in any typology you can possibly think of, from small countryside residences to grand-scale master plans. When did you have your breakthrough? It was about 7 or 8 years ago when we started doing our first city projects. Before that, I was working for Stephen Hall in New York, and I just came back to Moscow. And my father became the director of Mosproject-4. There was a time when we further collaborated with Stephen Hall and did a few projects in Moscow – the Golden Island, and the State Museum of Modern Art. We won the Tushino competition – and it was at that moment that we decided to focus more on the city projects. Unfortunately, the Tushino project was never implemented due to various circumstances. I think that the client very early on underestimated the economic costs, and, of course, specifics of working with Stephen Hall. Few clients can digest that. Ivan Grekov, KAMENCopyright: Photograph © Pavel Khomenko / provided by Osnova GroupWhat is the main problem that the architect is facing today? The housing typology sets very rigid constraints – you cannot do anything outstanding. And the demand for any other typologies is virtually nonexistent. You are very lucky if you do land such a project. For us, such a lucky project was the Moscow State University project that we did with Sergey Kuznetsov. So, unfortunately, you cannot really distinguish yourself in designing housing projects, even though my colleagues now and then do achieve the impossible, breaking the traditional frames. Moscow has a few such examples. Thank God, the mayor and the Chief Architect of Moscow support us in this. Can you name these examples? Definitely the Badaevsky and definitely RED7! And I am pretty sure that Silikatny will become another such project. But it still has to be implemented, and it will be a challenging task. This complex in the 2nd Silikatny Proezd – is it your boldest project so far? Well, this may not be the boldest project, but I really hope that this is the most interesting idea that stands a fair chance of being implemented. The client is literally fearless there. Osnova Group is a brave company – its RED7 project alone, designed by MVRDV on Sakharov Avenue, is sufficient proof of that. We have long since wanted to work with this developer, and we are very happy to have two projects with them. A client that can and wants to make a building that is “about architecture” is a big value and big luck. Apart from Steven Hall, who do you consider to be your teachers? Even before university, I was very much influenced by Vladislav Kirpichev. Sadly, I didn’t really hit it off with the Moscow Institute of Architecture… Then I enrolled at MARCH school, the very first course, then I studied at Sergey Skuratov studio, and this was an invaluable experience. And, of course, my dad, Vadim Grekov – we both live on architecture, and we’ve been heatedly discussing various projects ever since I was a kid. And you still do now? All the time! This really gives me an impulse. We are now running parallel courses, mostly criticizing each other, but this is not a bad thing. We all miss competent constructive criticism. How would you describe “competent constructive criticism”? That is a difficult topic. When I get criticized, I never take offense. Criticism is always good for you. You may not agree with the criticism but you still may find some valuable points in it. I think of criticism as something that’s going to make you better, not bitter, and, in addition, you don’t have to agree with everything they tell you. But, seriously, if it wasn’t for criticism, you would miss out on a lot of things. But criticism is often taste-driven, isn’t it? Yes, criticism is always test driven. The only way to effectively confront it is having a clear cut concept, when you are absolutely sure why you do these things, and why you don’t do other things, for example, look, you cannot make two white facades here, it’s like peeling an orange or sausage – it looks one way on the outside, and a different way on the inside. And when you are 100% sure of what you are doing, your critic will say “OK, you have a point!” But what if you really missed something? If you have this facade white, and this facade black, and you can’t explain why? If they say “Change this!”, and you cannot say why you cannot change it, this means that this thing escaped your attention, and you have to think harder. Ivan Grekov, KAMENCopyright: Photograph © Pavel Khomenko / provided by Osnova GroupHow “author” or “original” is your company? Do you delegate tasks? Our company is definitely an “author” one, but the role of the team is hard to overestimate. Of course, this is a collective creative activity. We create some sort of a common philosophy inside, but we generate it together, and the team is very important here. No matter who says what, we are all about teamwork. However, out of the 150 people that we have, only 5 or 10 generate new ideas. We have a conceptual division. We have plans for mixing up our team, but these are plans for the future. So far, this does not go well together with our philosophy. And what is your philosophy about? What do you want to get from your architecture? First, we are trying to get maximum customization from every project. We have an approach of our own that allows us to achieve that. But then again, pretty much everyone else does the same. When we start a project, we do a lot of research: the history of the place, the spirit of the place, the economic performance expectations, the functions, and so on. However, our next main task is to create a clear structure, a hierarchy, and to form the idea. Then we get some locomotive idea that usually consists of five bullet points at most. And we try to make sure that these five bullet points are different from project to project, unique for their place and their task. Hence, the task of designing unique things suggests itself. And then, there is also a goal that is important for any architect – you need to develop your personal formal lexicon. We are just groping for it. But, the way I see it, something is already in the pipeline. |

|