|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 04.08.2022 | |

|

A High-Rise Erector Set |

|

|

Tatiana Shovskaya, Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Sergey Nikeshkin | |

| Studio: | |

| KPLN | |

|

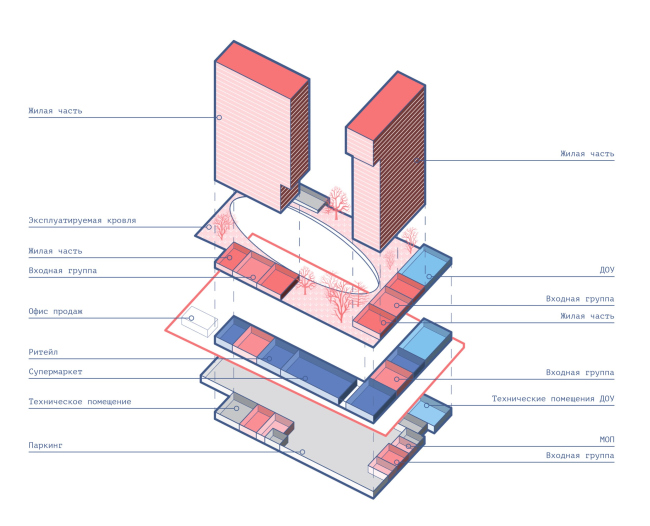

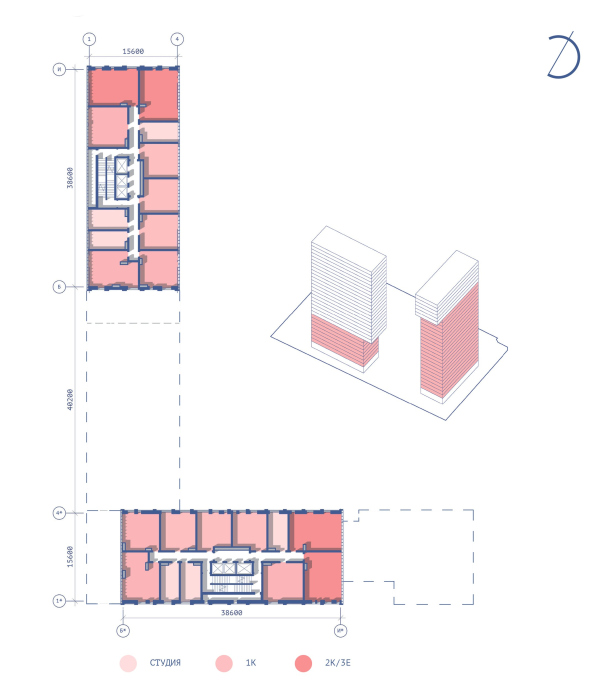

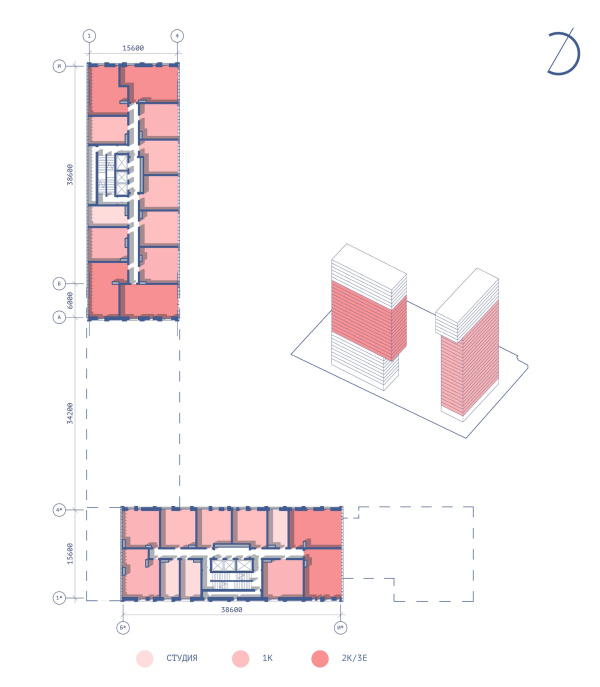

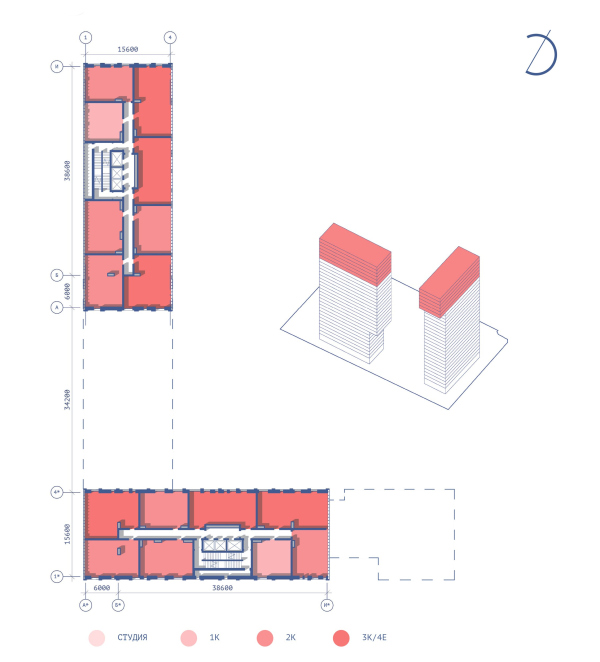

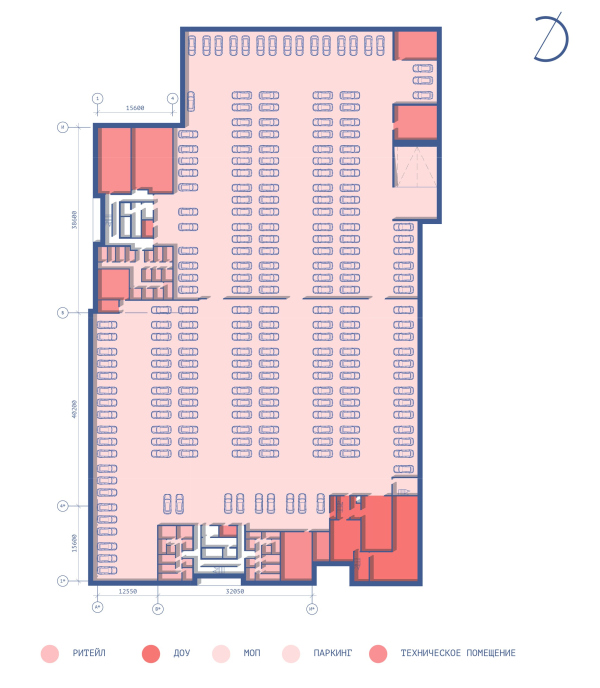

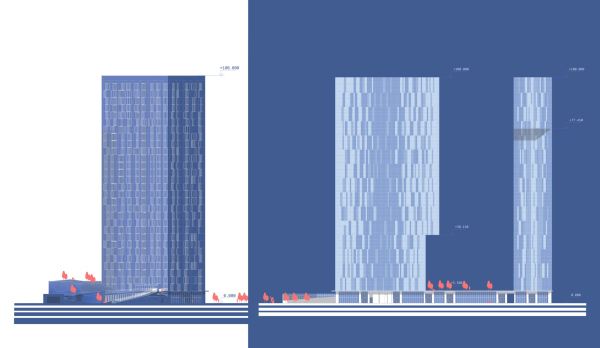

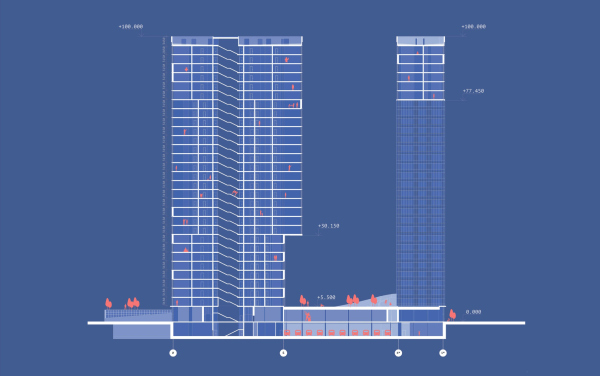

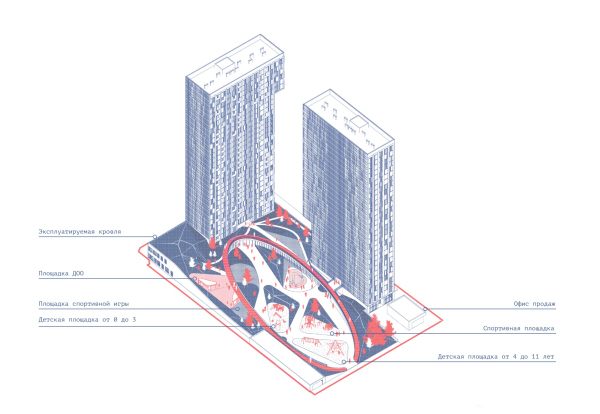

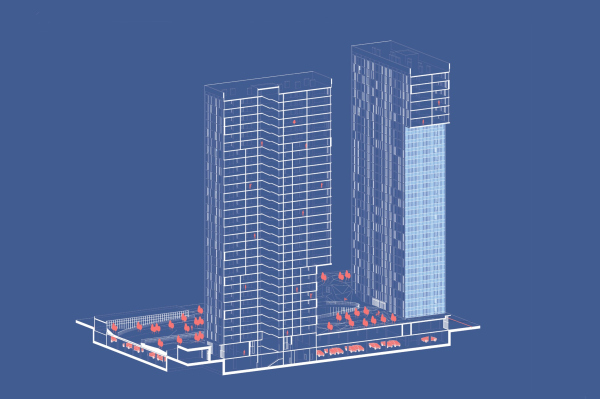

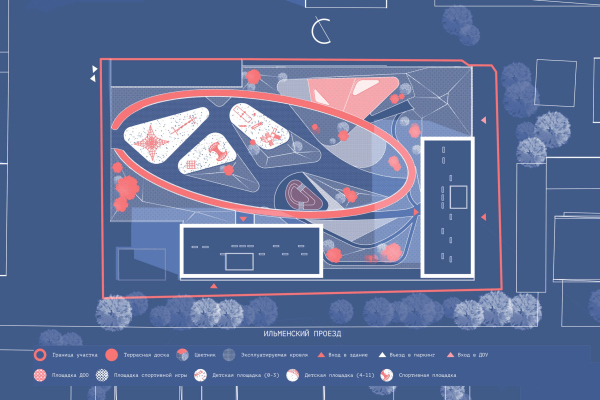

In this article, we are examining one of the projects submitted for a closed-door competition for a housing complex to be built in the north of Moscow. The KPLN architects proposed a simple volumetric pair of 100 meter high towers, united by a common sculptural design based on laconic contrast, yet dramatic at the same time. Another interesting thing is an oval yard that is “carved out” in the stylobate roof. The project was prepared for a closed-door competition, conducted in 2021 for a land site in the north of Moscow. The land of the former industrial parks lying between the Dmitrovskoe Highway and the Northeast Chord is a spacious and convenient place for new construction; currently, it is being intensively developed with various housing projects. Across the street from the site in question, there is an already-complete large housing complex built by a well-established development company; nearby, there is yet another one, consisting of blocks of varying colors and heights. Today, the client is developing the neighboring site. The project that we are examining in this article did not win the competition; such projects are rather numerous in Moscow today, and we believe it will be interesting to cover them later on as well. At the architects’ request, the exact location of the site remains undisclosed. Ilmensky Level housing complexCopyright: © KPLNOn the plan, the towers look elongated, and are nothing like a perfect square, which yields a small corridor running on either side of the elevator core. Their volumes are placed along the borders of the site at a 90-degree angle, and are fitted with cantilevered structures on one of the side ends: the “head” of the tower positioned crosswise “gazes” upon the street outside, the other one is positioned longitudinally, gazing south. This way, a dialogue appears, and at a first glance one may think that the cantilevers are identical, but then you realize that one of them is significantly higher, and you can imagine that these two volumes are matching pieces of one simple puzzle that you can turn round, put together – and they will fit perfectly. This is a very common and fail-proof technique for coming up with flashy and laconic solutions for large-scale forms. Ilmensky Level housing complexCopyright: © KPLNThis “turning” game continues on the facades, albeit in a different way: the facades launch a narrative of their own because the street is overlooked by glass surfaces, and the sidewalls are executed in brick. Thus, it turns out that in one case glass is used on the sidewalls, and in the other on the longitudinal surface: as if the building’s redline was “sliced” with some hot wire so that the surface around the cut melted slightly. The regular and the tinted kinds of glass form one single surface; it is livened up by asymmetric pixel inserts of glass of a lighter shade, whose strokes unite each two floors. The brick is dark, and the facades made of it are interpreted as a textured grid of multiple piers, not devoid of the inherent classic character of American skyscrapers: a flat frieze band on top and vertical “blades” running the entire height of the building. Ilmensky Level housing complexCopyright: © KPLNInside this grid, the windows are separated by slim horizontals, also indulging in pixel asymmetry, rather lively, and – thanks to the recessed balconies – volumetric, akin to some kind of an ancient “cave” city. This way, two surfaces appear: one can see in them a contrast between black and white, earth and sky, yet at the same time rendered more subtle by the nuances of the transparency and the color of the glass, as well as the color and the texture of the brick facades. Furthermore, this pixelization of glass is something like a projection of the brick relief, which brings us back to the “slice” associations: one can easily imagine that the towers are “made” of a material with a certain uneven internal structure, which is rough and textured on the outer surface, but behaves differently on the polished section – retaining at the same time the general principles of construction. This is also one of the ways to endow this pair of buildings with internal integrity; in this case, it is combined with the material component and context – brick responds to the facades of neighboring complexes, while the glass sets a new theme.  Ilmensky Level housing complex. Version 1Copyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. Version 1Copyright: © KPLNThe apartment range of the complex correlates with its form making. As a matter of fact, it is the changes in the floor plans that determine the changes in the plastique of the volumes, and this organic combination is something that the architect Sergey Nikeshkin believes to be very important. One tower has in it two types of floor-by-floor plans, the other has three. In the floor plans of the upper floors, the apartments become larger, the share of studios shrinking. Each of the towers is equipped with just one vertical communication core, which spells a corridor system, but this does not affect the floor plans negatively – the complex refers to economy class, and the overwhelming majority of the residential units is constituted by studios and single-room apartments, which by definition are designed in lines, and the larger apartments are placed at the building’s sidewalls. The entrances of the two towers are see-through, and their lobbies are designed as a double-height space.  Ilmensky Level housing complex. Plan of the 1st floorCopyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. A simplified plan, type 1Copyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. A simplified plan, type 2Copyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. A simplified plan, type 3Copyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. Plan of the parking garageCopyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complexCopyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. A section viewCopyright: © KPLNThe towers rest on a stylobate that occupies the entire site almost on the redlines. The stylobate, in turn, organizes the courtyard and hosts a set of necessary functions – stores, a kindergarten, and other public places. Ilmensky Level housing complex. The functional zoningCopyright: © KPLNThe oval yard on the stylobate’s roof refers to the images that are rather unusual for Moscow suburbs, for example, to squares of late Italian Renaissance – amongst the former industrial parks shooting off housing complexes, this technique looks unconventional and positive. The roof of the stylobate grows lower as we go deeper inside the block – the father away from the highway the quieter; in addition, its space is double-height, which enhances the privacy of some zones, making them look separate from the street outside, at the same time maintaining the visual contact with the city. This “distributed zoning”, generally valuable in high-rise projects, where the residents value not only their own apartments, but also a competently organized fragment of the city of their own – is a very interesting feature of this project.  Ilmensky Level housing complex. AxonometryCopyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. An axonometric section viewCopyright: © KPLN Ilmensky Level housing complex. The master planCopyright: © KPLN*** The contest, however, was won by this project.  The Level Seligerskaya project can be seen on the website The authors of the final version according to the project declaration: Metropolis & Simple Project. |

|