|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 21.10.2021 | |

|

The Spinning Vibe |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Sergei Tchoban | |

| Igor Chlenov | |

| Studio: | |

| SPEECH | |

|

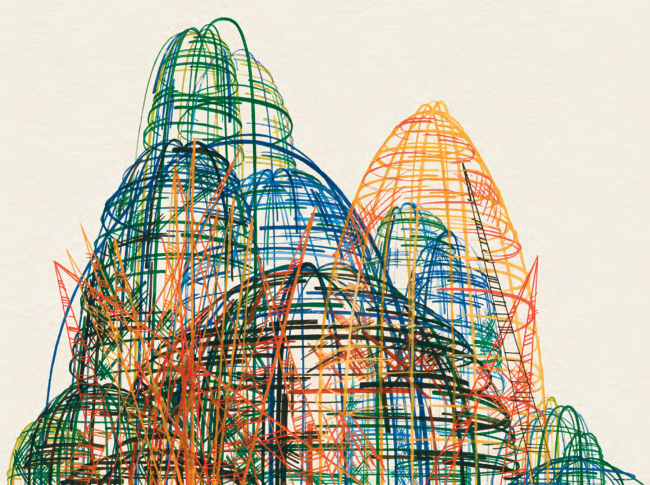

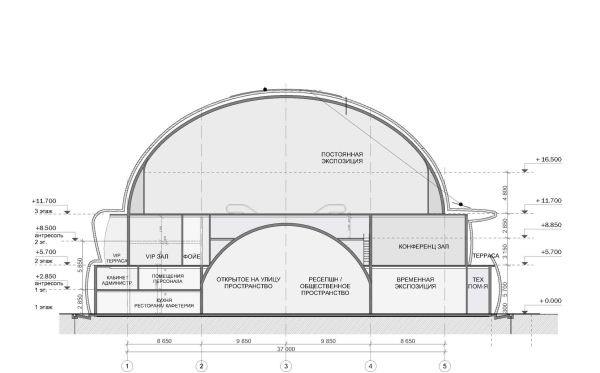

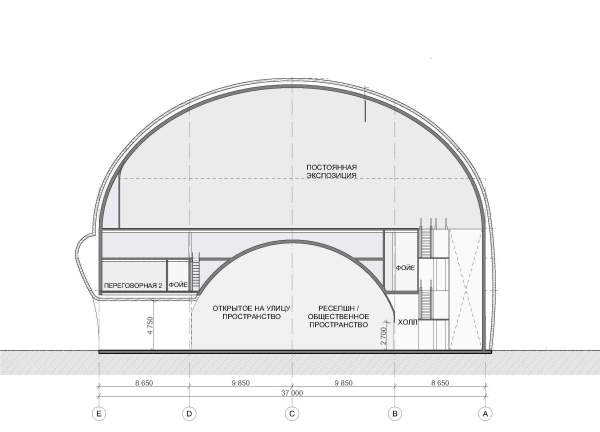

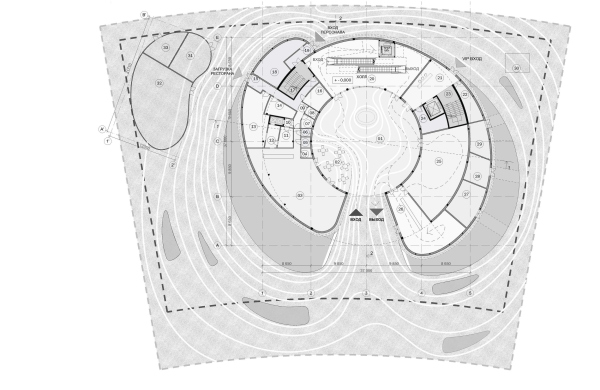

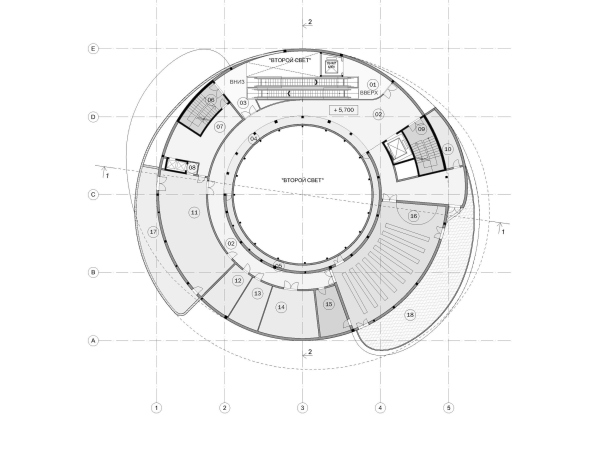

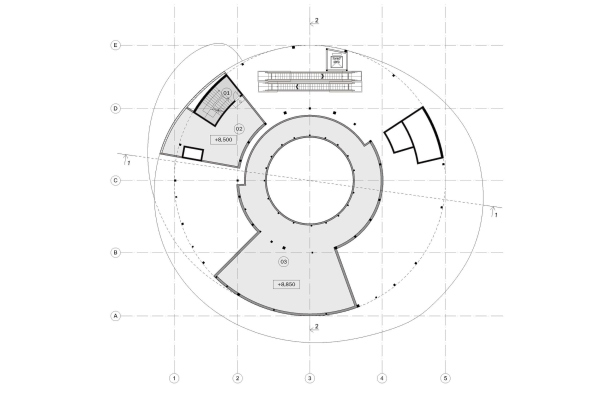

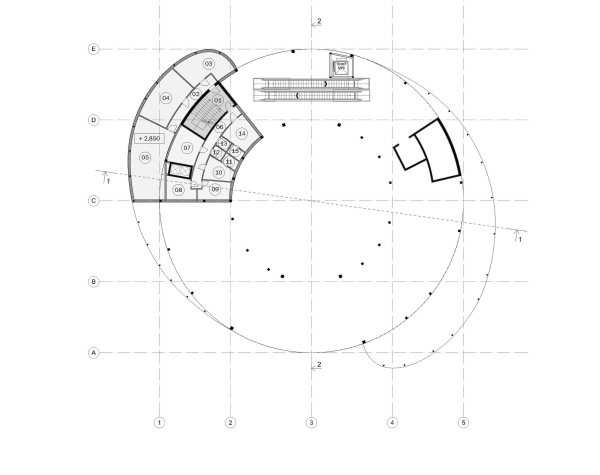

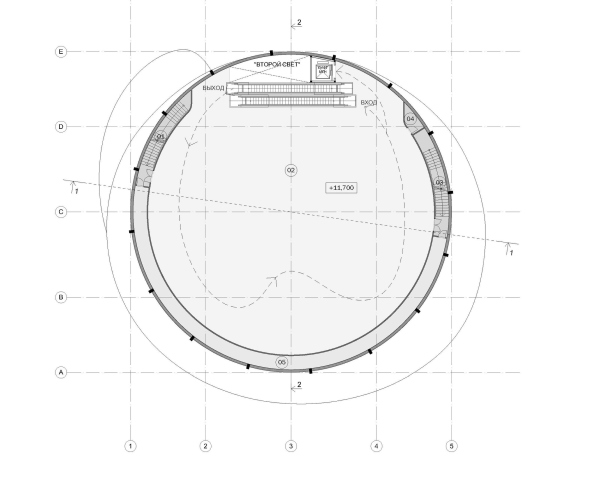

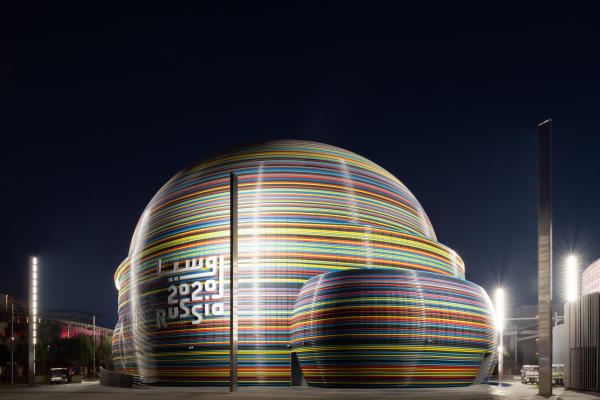

The pavilion designed by Sergey Tchoban for the World EXPO 2020 in Dubai is a bright and integral architectural statement, whose imagery can be traced back to avant-garde graphic experiments by Jacob Chernikhov, but allows for multiple interpretations. The pavilion looks both like a dome temple, a spinning “Planet Russia”, and the head of a matryoshka doll. Still more interestingly, the core of the exposition is a “brain”. In this article, we take a closer look at the interpretations and the subtleties of the implementation. Sergey Tchoban began designing the Russian pavilion for the World Expo in Dubai back in 2018 in collaboration with Simpateka Entertainment Group. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHAccording to Sergey Tchoban, the key idea – that of two domes inside and a ball of multicolored lines on the inside – presented itself almost at once. This design solution can be traced back to graphic experiments by Jacob Chernikhov, the architect of Russian avant-garde. Chernikhov proposed many different approaches to graphics, one of them being based on dynamics of the form manifesting itself through free spinning of multicolored lines; examples of this technique can be seen here and here. Jacob Chernikhov. Architectural fantasyCopyright: Photo from the presentation of the project of the Russian pavilionThe original sketches by Sergey Tchoban do indeed demonstrate parallels with Chernikhov drawings – different lines form a “knot” charged with energy. A sketch. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © Sergey TchobanThe chosen topic successfully combines a subtle reference to Russian avant-garde – which, as is known, defines to a large extent the contribution of our country to the development of the world culture – and serves to explore the subject of “mobility”, which was prescribed by the EXPO administration for the segment of the exhibition where the Russian pavilion is situated. Mobility and inner dynamics are indeed acutely felt, yet at the same time this dynamics is pretty special. The ball of lines seems to be offering to us an image of “movement in itself”, movement not in the sense of moving from point A to point B, but movement akin to electrons circling their orbits, or tense magnetic fields the way they are pictured in physics textbooks. Akin to pure energy of a graphite rod or some sci-if motor, composed of force lines, whose nature is, of course, material, but belongs to the upper hi-tech kinds of matter, and virtually weightless thanks to the inner charge. Some kind of levitating tectonics appears, existing independently from gravity – on the verge of an avant-garde dream and the messages from the neighboring EXPO exhibitions, many of which are also filled with a spirit of similar reality of futuristic fantasies. A sketch. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © Sergey TchobanIn addition, the shape proposed by the architect is integral and abstract enough to allow for different interpretations and meanings. It resembles a lot of things, from the domes of Bukhara and Samarkand to a ball of yarn or wire, to a turbaned head, or even Saturn with its whirling rings. In the agility of the billowing lines one will be able to see, as the authors hope, the dynamics of the development of our country, as well as its multinational population, and the bright variety of “Planet Russia”: “Russia is a planet around which a lot of things revolve, and which, at the same time, is turned outward. There are many different things in Russia – 200 nationalities, a huge number of religions, opportunities, events and tendencies, they form a complex and interesting tangle…” Sergey Tchoban explains, speaking about his plastique statement, expressed in the pavilion, as a very sincere concept that came about almost at once. At the same time, if we are speaking about interpretations and meanings, it must be noted that nothing here is presented “at face value”: even the reference to avant-garde is devoid of direct recognizability, and you will not see any cliched “red wedges” – the technique is perceived as quite modern and resonant with the creative search of not only the 1920’s, but of today as well. It is even more interesting how this idea, so brave plastique- and energy-wise, was implemented. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe lines (or the “threads”) are made of thin aluminum pipes 8cm in diameter, bent in accordance with the geometry that the authors thought out and calculated in the BIM software. The pipes are coated with a color polymer formula, resistant to sunbeams and even sandstorms, which do happen in the Arabian desert – the pipes must maintain their glitter and color both during and after EXPO. Originally, as Sergey Tchoban shared with us, the architects considered using transparent pipes glowing from the inside, but they were rejected precisely because of their poor resistance to physical damage.  The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe total length of all the pipes is 46 km, the number of fragments that the cladding is composed of is more than 1000. The pipes are attached to the metal walls of the pavilion from the outside on special brackets, barely visible. At one point, the architects considered the idea of pulling some of the pipes further forward, but then the brackets would have become visible; now you have to look really hard to see them. Due to the glittering surface, mutual reflections appear. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe shell made of color pipes – a beautiful and unconventional solution – allowed the architects to accurately implement the idea of multicolored lines. It is great for the pavilion format, which is generally big, but not excessively big, and is much better than aluminum panels, no matter what kind of pattern you apply to them. Besides, this solution, as Sergey Tchoban shares, is also cost-effective and environmentally responsible. Here is the thing – wood (which has somehow become the hallmark of environmentally responsible solutions) is extremely scarce in the Arabian desert; if you want to build something from wood (or clad it in wood), then you will have to bring it to the Emirates from really far away (for example, the cladding of the Polish pavilion was shipped all the way down from Poland). Shipping spells expenses and carbon emissions. Meanwhile, active construction is underway in Dubai, facades are clad mainly with aluminum, this material is abundant here, and local construction companies have good experience in working with it. The construction of the Russian pavilion was carried out by the Abu Dhabi-based company Inventure, using the same aluminum that is common at local construction sites, which made it possible to save money and get a predictable speed of implementation combined with a high-quality result. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHIt was originally planned that the background for the outer shell of color pipes – the metallic walls – would be made pitch-black for better graphic contrast in the spaces between the lines. However, the pavilion was assembled in summer in more than a 40-degrees heat, and working next to a black surface turned out to be dangerous for the construction workers, so the background color was changed to gray – Sergey Tchoban shares. This facilitated the assembly process and was compensated by a large number of black pipes, thanks to which it was possible to enhance the contrast and even – using the optical effect that the black color is perceived as lying deeper – make the perception of the surface more complex: when watched from a distance, and even from a side, at a glance it is perceived as slightly textured, as if some threads were pushed deeper, and some pulled forward. The six shades of color form different combinations, varying the thickness of the bands and the frequency of usage, yet at the same time following the contrast principle and avoiding placing similar colors next to each other so that they would not bleed into excessively wide bands. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe shallow pools, made around the pavilion, partially follow the trend of the Dubai exhibition to add water wherever possible – but to a larger extent, just like the mirror above the entrance group, serve to reflect and multiply the pattern. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe pavilion has three levels in it, its metallic construction being based on two domes installed on top of one another. The minor dome at the bottom level serves as a lobby where the visitors, should lines form, can stay waiting to enter in a cool and air-conditioned space (currently, the pavilion is visited by about 8,500 people a day; in inter, during the peak period, 25-30K daily are expected). The entrance to the dome lobby. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHA sketch of the entrance lobby. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © Sergey TchobanIn the center, there is a reception desk, surrounded by extra premises of a cafe, a restaurant, and a souvenir store – on the outside, these form rounded bulges, which serve as some sort of a sculptural base. Between the bulges, there is a recession of the entrance. Here, the superposition of the colorful lines on top of each other is particularly prominent. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHHigher up, in the second tier, there is a block of conference halls and meeting rooms for negotiations and presentations; such a closed-door area is also present in the pavilions of many other countries at EXPO; it is necessary for the pavilion to fully perform its representative functions. While the interiors of the public lobby and the exhibition hall are black, the representative floor is white. The exhibition visitors bypass it, traveling by escalators to the third floor, where the main hall is situated.  The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe roofs of the cafes and shops of the first tier support open-air terraces of the second representative floor; one of them is covered by a ledge – and the volume receives a “canopy” which enhances its likeness to a human head. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe terrace under a canopy in the representative zone. A sketch by Sergey Tchoban, 2020. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © Sergey TchobanThe whole of the top floor – the main exposition one – is occupied by a dome: 36.4m in diameter, 14.37m high. The dome gives a spacious interior with a black ceiling and “stars” of the pinpoint lights.  Sergei Tchoban, SPEECH, Tchoban Voss Architekten, Chart Studio One of my main ideas was to create a powerful exhibition space – tall, spacious, and pillar-free, with a single-span ceiling. A space that can host a big and impressive show. The solution was a dome; it was important that it should be placed in the top part, not surrounded with anything, and not pierced with columns, having the maximum possible diameter. Basically, a dome is a near-ideal solution for placing an emotionally charged, dramatic exposition, giving you plenty of air, a lot of height, and an opportunity to set up a large object in it. In addition, the domes are well known in the Russian architectural tradition, including double domes, domes on top of each other. As for the two domes, big and small, Sergey Tchoban likens them to a matryoshka doll, where one head is inserted into another, and to double shells of the domes of the Renaissance and Classicism epochs. A sketch. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © Sergey TchobanSome similarity is indeed there, particularly if you look at its cross-section view. However, I will note that the shape of the main dome on the outside is not adjusted or corrected in any way, and keeps its “honest” slightly flattened “oriental” proportions: radius 18.2m, height 14.37m. This kind of honesty in the display of the structure is reminiscent of the rules of early modernism and the eastern and Byzantine domes in equal measure. At the same time, the dome of the bottom lobby is connected to the upper one not so much construction-wise as emotionally: it prepares the visitor, exposing them “on a miniature scale” to the spatial effect that awaits them upstairs – which looks a little bit like the exonarthexes in a Byzantine churches or palace lobbies, while the composition consisting in placing the minor dome precisely underneath the main hall resembles large churches of the Russian Empire of the 19th century on high basements.  The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: © SPEECHThe exposition, designed by Konstantin Petrov and Simpateka company, supports and develops to a large extent the image of a “matryoshka doll” or a “human head” readable in the project – because in the center of the hall the architects placed a generalized model of the human brain as a basis for projections, consonant with projection globes in a number of other pavilions, but with a more complex wavy surface. The topic of the exhibition is “the mechanics of wonder”, by which the human brain is meant. In the beginning of the demonstration, the model is divided into two parts, revealing its mechanical insides. The exposition is executed at a good modern level of multimedia; it does not lag behind some of the pavilions of the exhibition, and has a significant lead over some of the others. Another thing that is remarkable are modules that allow you to see the world through the eyes of reptiles, insects, and other living creatures. The interactive floor around the “brain” also works great.  The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHOne of the big advantages of the solution used in the Russian pavilion is the ease of the system of sessions: we see the countdown of seconds before the start of the show, but no one closes the door and you don’t have to wait in line. For comparison – the show in the Japanese pavilion lasts an hour and you have to wait for it for more than an hour in front of closed doors. Let’s get back to the visual design of the pavilion, though – as Sergey Tchoban noted, just like Russian architecture historically from time to time paid more attention to the outward appearance than the inner space of the building, so the architecture of the pavilion, forming space for the multimedia exposition, at the same time works to a large extent for the outside perception. This peculiarity is composed of two parts: sculptural/coloristic and spatial/town-planning. Let’s start with the second one. The radial-and-ring plan of EXPO, subjected to a three-leaf pattern, forms a whole number of crossroads. The crossing of the Horizon Avenue that outlines the petal of Mobility and the GAFA Avenue that leads to the shuttle bus stop near the main entrance is one of them. The Horizon Avenue bends smoothly, and the Russian pavilion, which is rather large, finds itself at the end of several perspectives at once, forming the so-called “Instagram points” and serving as a noticeable landmark, among other things, due to the fact that it is different from many other pavilions at the exhibition. It is different in several respects. First, the building is a colored sculpture; it combines two very strong means of expression. What you see more often are multicolored volumes of simple design or volumes of complex plastique, but neutral color. In our instance, however, the color and the form are intertwined in a single knot. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHThe other difference, strange as it might seem, lies in a somewhat “old school” solution. At EXPO 2020, more than ever before, media screens and projections are shimmering and glittering all they can. In the dark, videos inside the pavilions echo the media shows on the facades, creating a hyper-neon (or post-neon?) celebration. The pavilion of Saudi Arabia is, by and large, one giant media screen. The British one highlights poetry created on-site by AI. The exposition of the pavilion of the Russian Federation inside is the same, media-based and animated; essentially, it is a three-dimensional video-diorama, into which the visitor is immersed, and which is meant to mesmerize them. On the outside, however, the architects limited themselves to a powerful, yet still traditional, backlighting composed of spotlights arranged in a circle, “catching” the volume out of the darkness, showing a solid outline of the silhouette and even the shine of the surface of many of the pipes – Sergei Tchoban compares it to the usual night illumination of architectural monuments in historical cities. Such regular lighting makes the pavilion, when viewed from the outside, very constant image-wise, as opposed to the media dances that begin at night all around. It stays unchanged during the day – and almost the same at night. It glows with reflected light and confidently presents itself in space, with all the dynamism of twisting going on all around – paradoxically calm and motionless, like a thing in itself. It attracts attention as a kind of “rock” surrounded by a turbulent exhibition river.  The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECHFrom the architectural standpoint, the solution turned out to be meditative in an oriental way, to a large extent thanks to the dome, the centric space inside and a collected rounded form on the outside. Comparing the pavilion of 2021 in Dubai with his own design of the pavilion at the previous EXPO, 2015, in Milan, Sergei Tchoban recognizes a fundamental difference in approaches, motivated by the cultural context: in Europe, he relied on the impulse and aspiration of the mirror cantilevered structure forward and upward, and here his bet was the rather eastern approach both to color and to the theme of movement, not so much flying into the unknown, as whirling and abiding. He showed the component of the Russian soul thar is consonant with the oriental tradition. The pavilion representing the country at an international exhibition of such magnitude is a difficult task in many respects. If we talk about an architectural image, then, if it is successful, it should balance on the brink of a unique and contemporary form and statements on the topic of centuries-old history and national tradition, at the same time being a bright, noticeable, and attractive plastique statement. It must also respond to the general context of the exhibition and the country in which it is currently taking place. It’s not an easy task, I’ll repeat, but in this case, practically all of the conditions have been met – the volume is indeed iconic, based on a single solution, and multi-valued, as it should be for a building that symbolizes a large, complex, and multi-component country. This was Sergei Tchoban’s second (very much unlike the first) answer to the question about the image of Russia. At this point, we cannot help remembering that “Russia is a sphinx”. But then again, in this particular instance, some other enigmatic creature is letting people inside its head, where it even makes an attempt to explain how his or her thinking is wired, making an attempt to unveil the mystery of mysteries. I wonder if anyone will come out of the pavilion with better knowledge than before about the difference between the limbic brain and the cortical, and the difference between the emotional and rational, not to mention the understanding of the “Russian soul”. But the very attempt deserves respect. The Russian pavilion at the World EXPO in DubaiCopyright: Photograph © Ilia Ivanov / provided by SPEECH |

|