|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 02.08.2021 | |

|

Stream and Lines |

|

|

Lara Kopylova |

|

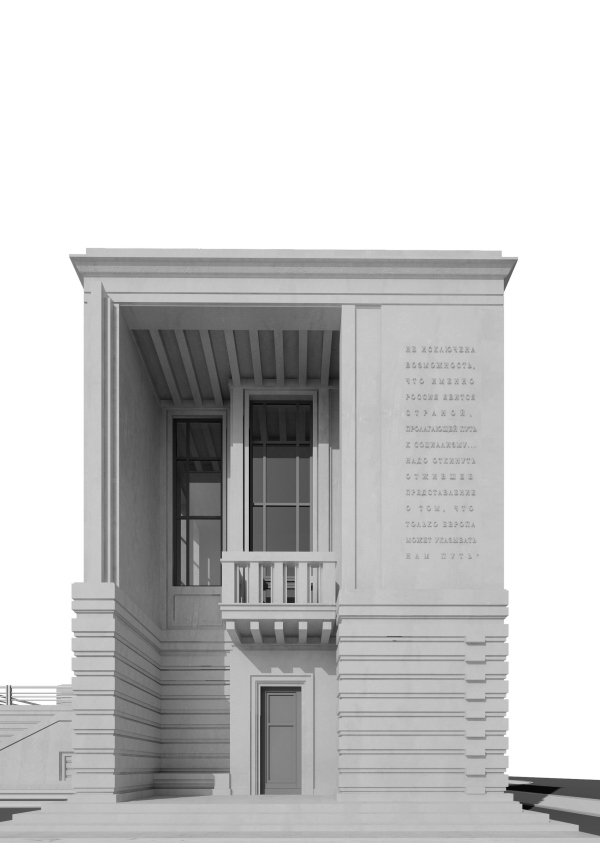

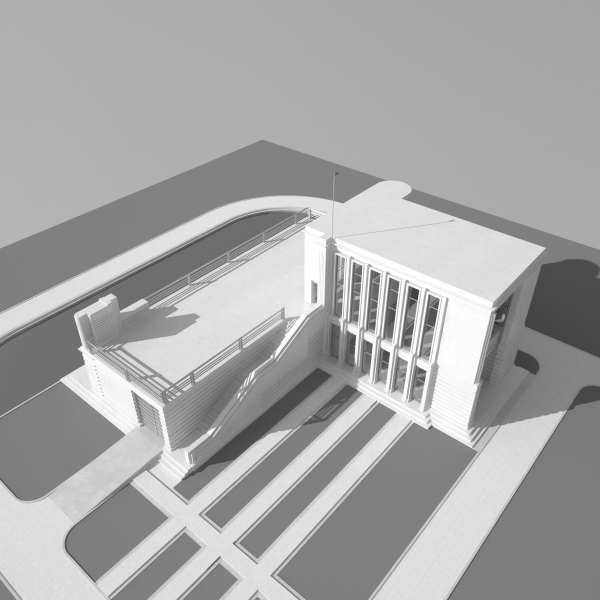

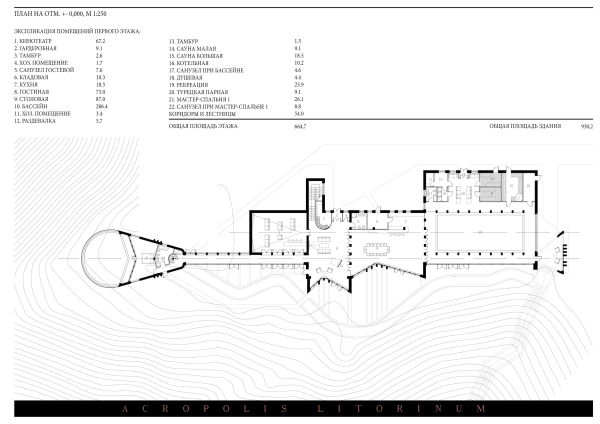

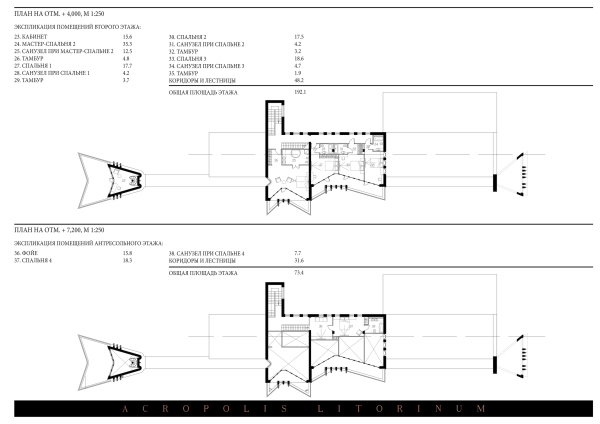

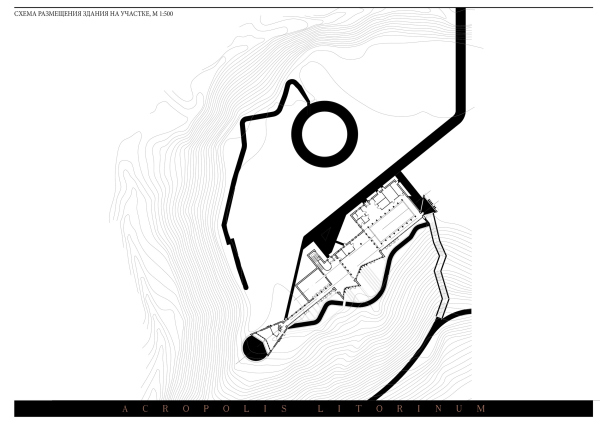

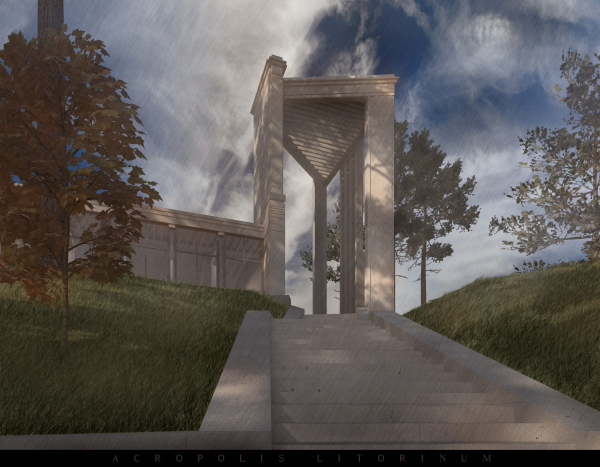

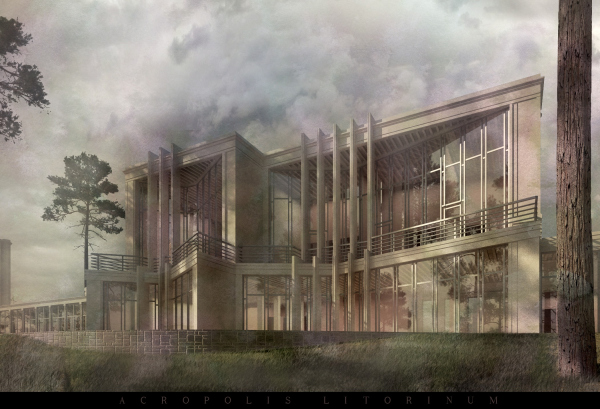

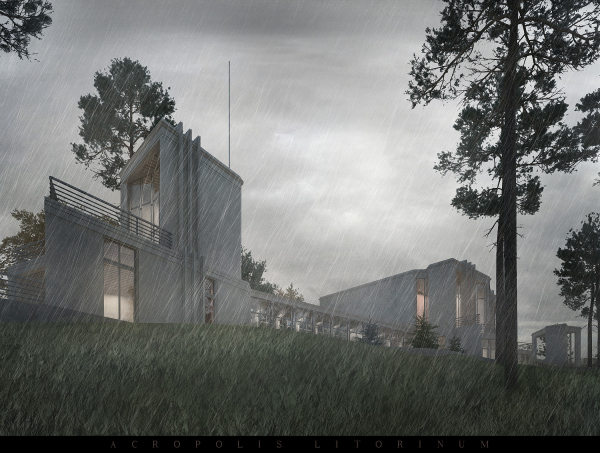

| Architect: | |

| Stepan Liphart | |

| Studio: | |

|

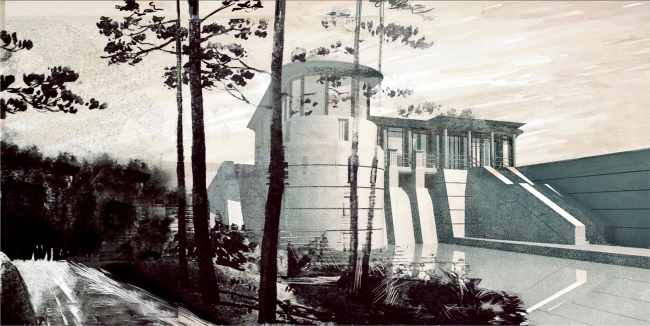

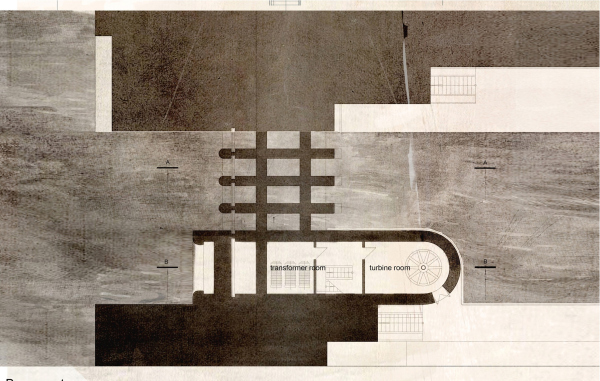

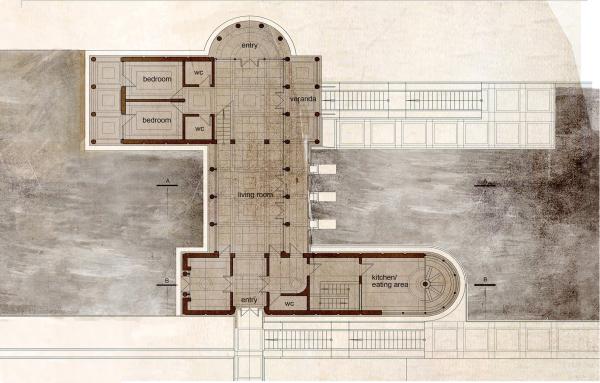

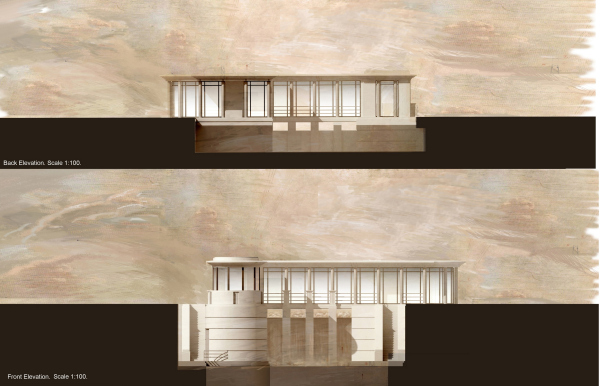

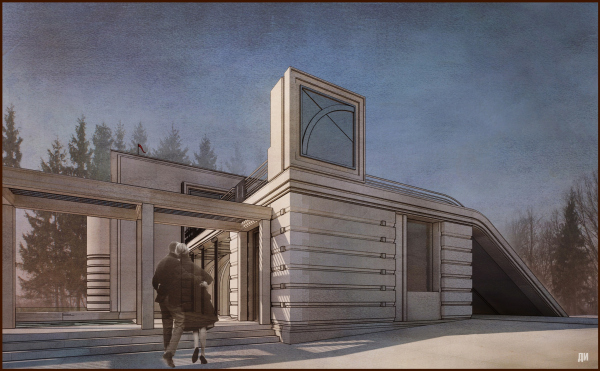

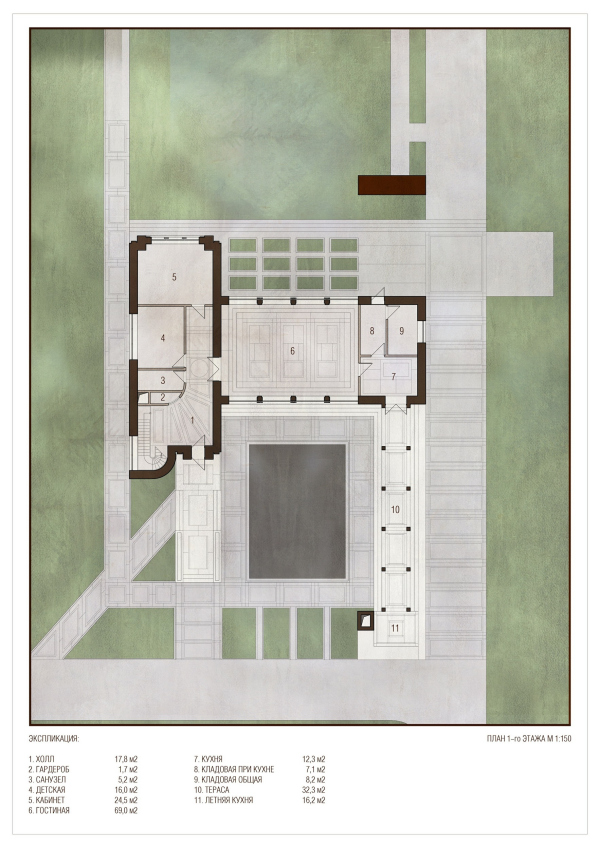

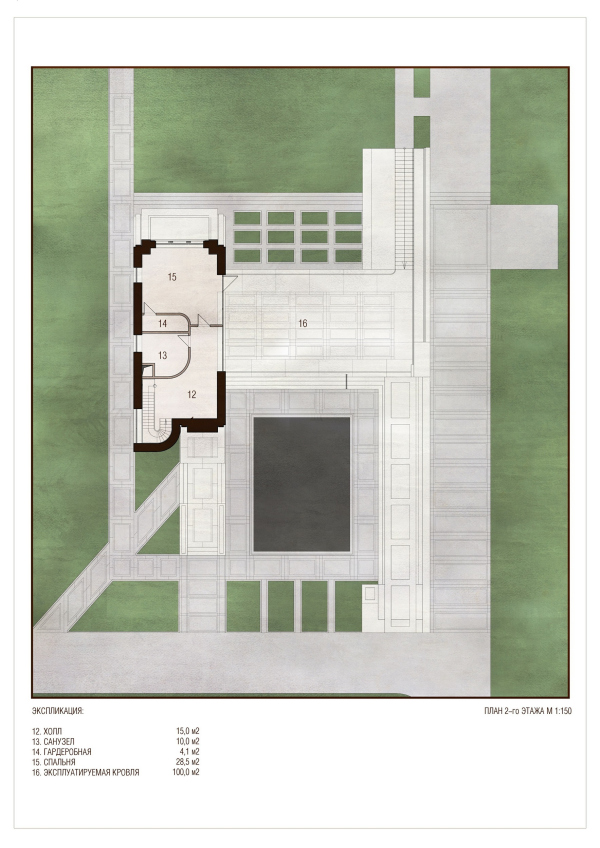

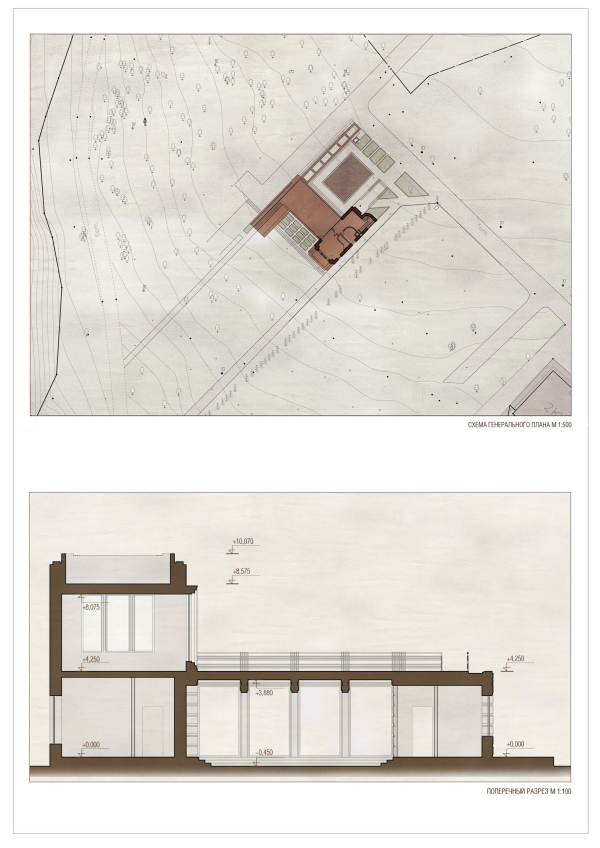

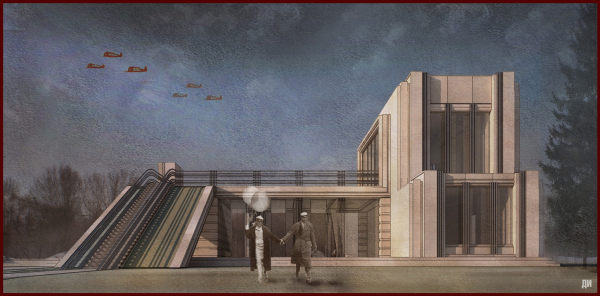

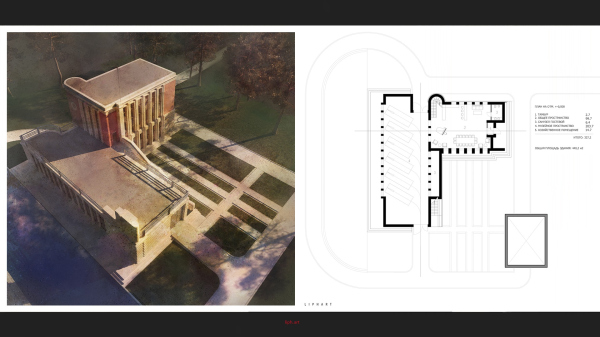

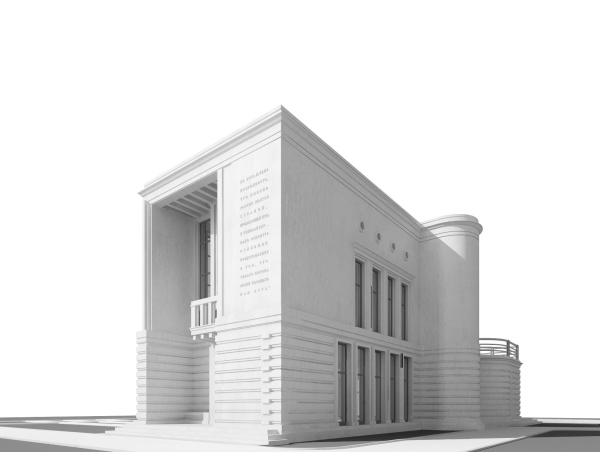

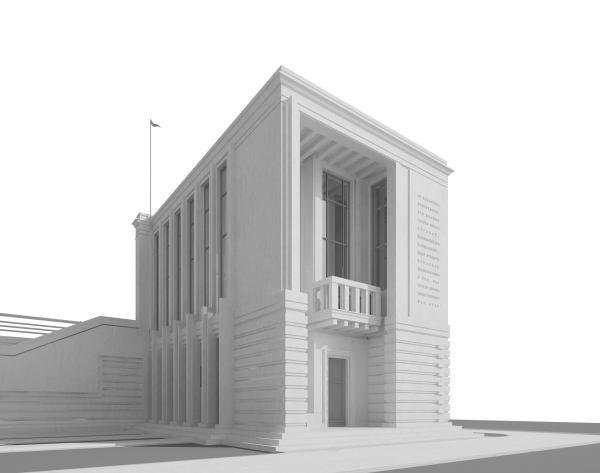

Stepan Liphart’s projects of Art Deco villas demonstrate technical symbolism in combination with a subtle reference to the 1930s. One of the projects is a “paper” one; the others are designed for real customers: a top manager, an art collector, and a developer. If Russia of the 1930s had not chosen the socialist path and had become a bourgeois democracy, possibly, private residences would have looked like houses designed by Stepan Liphart. The portrait of the customer for these three villas is far from simple because it requires an exposed life, as if you were constantly being filmed in a movie. Another thing that comes to mind is the architect Mallet-Stevens – not his Art Deco Paris mansions and villas (which are closer to modernism), but his “dandy” image and his work as a Haut Couture artist. The Stepan Liphart villas, on the other hand, demonstrate some “pan-aesthetic” course to the future, this course lying through the impending dark ages, which even yields a heroic note in the pan-aesthetic concept laid out before us. The “Hydroelectric Power Station” house. The project for the international “Dom-Avtonom” competition was performed within “Jophan′s Children” creative group. Graphics: Boris KondakovCopyright: © Stepan Liphart, Boris KondakovThe conditional Dorian frieze with triglyphs separates the bottom tier of the building from the top one; the residential enfilade above the waterfall is a gallery with columns that asserts humans over the crushing power of the cascading water. On the one hand, what we are seeing is the conquest of the water element, and on the other – the combination of human, technological, and natural energy into a single whole. This synergy has a prototype.  Stepan Liphart, , Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been greatly impressed by the buildings of the Moscow Canal, the spirituality of their essentially functional architecture, which looked particularly impressive when the gateway locks were in operation: how the water rose in them, how the giant ships gradually rose to the level of the openwork turrets and belvederes. Rukhlyadev and Krinsky, functionalists, who in the 1920s boldly experimented with form and space, combined here their avant-garde experience with classical material, and the fruitfulness of such synthesis and synergy is quite obvious. On the other hand, the scale of these hydraulic structures is close to the typology of a large country house. So the image of the “hydraulic power station” is in the return from the gateway to the villa.  The “Hydroelectric Power Station” house. The project for the international “Dom-Avtonom” competition was performed within “Jophan′s Children” creative group. Graphics: Boris KondakovCopyright: © Stepan Liphart, Boris Kondakov The “Hydroelectric Power Station” house. The project for the international “Dom-Avtonom” competition was performed within “Jophan′s Children” creative group. Graphics: Boris KondakovCopyright: © Stepan Liphart, Boris Kondakov The “Hydroelectric Power Station” house. The project for the international “Dom-Avtonom” competition was performed within “Jophan′s Children” creative group. Graphics: Boris KondakovCopyright: © Stepan Liphart, Boris Kondakov The “Hydroelectric Power Station” house. The project for the international “Dom-Avtonom” competition was performed within “Jophan′s Children” creative group. Graphics: Boris KondakovCopyright: © Stepan Liphart, Boris KondakovEvidently, such a house will not lack light and warmth. Sitting on top of an energy flow and transforming its energy for the best purposes is probably the mission of a potential owner of such a villa. One cannot help but remember Director’s House in the Ideal City of Chaux designed by Claude Nicolas Ledoux, where the river flows through the cylindrical part of the house, without bringing any practical benefits whatsoever. Another thing that comes to mind is the iconic building of the XX century, the idol of all architects, the Fallingwater Villa, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, in which the part of cascading water is also purely decorative. Wrapping it up for historical associations, I will remind you of the incident with Le Corbusier, who once, accompanied by a poet friend of his, visited a constructed dam in the Alps, expressed his admiration to the escorting engineers, but was misunderstood. Here is how he describes this incident: “We tried to explain it to them, why we found the dam so marvelous: the sheer scale of such work, applied to the practice of city construction, could become a total game changer. And suddenly, these people were indignant: “What? Do you want to maim our cities? You are real vandals! You forget about the rules of aesthetics!” Probably, you could say that in the “power station villa” this conflict has been resolved: the aesthetics of the Order and the technological energy coexist quite peacefully here. The ITR villa The ITR acronym stands for “inzhenerno-tekhnichesky rabotnik” (“engineering and technical coworker”), an early-Soviet term, the difference being that, of course, the Soviet ITRs, for very few exceptions, could not afford to live in villas, and, even if they did have a country home, it was a regular dacha. The country house was designed in 2011 for the son of a well-known developer. At that time, the client headed an industrial enterprise, meaning, with a certain stretch you could describe him as an “ITR”. Hence the image of the villa: a residence of the technocratic elite. The aerodynamic streamlined design, multiplication of lines in the metallic railings, parallels in verticals, and rounded corners – all these techniques refer to one of the variations of Art Deco, specifically, streamline, characteristic for the industrial design of the 1930s, from cars and steamboats to dirigibles… with an adjustment to our epoch.  ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartThe villa in fact consists of two units, perpendicular to one another. The two-story unit includes bedrooms; the single-story one, glazed, includes a living room and a kitchen. The roof of the first floor supports a grand terrace, which can be accessed both by the inner staircase leading to the hall of the second floor, and directly by the monumental stairs of the main facade. The key idea of the outdoor staircase is motion, enhanced by the decorative stream of water, cascading next to it. Many people, me included, took this staircase for an escalator at first, because the graphic lines of the railings and barriers create an impression of flowing dynamics of a conveyor belt in operation.  ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart ITR villa: a private residence in the Chekhovsky district of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a private client, 2011, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartThe moving aesthetics are also tied up with the ergonomics: underneath the staircase, there is enough room for a vehicle to drive in that delivers groceries to the kitchen via a special shaft, while the kitchen elevator, situated in a bas-relief-decorated buildup, elevates the meals to the rooftop. The main facade is framed by a small mote with a “colonnade” pergola stretching along it and ensuring the connection between the main kitchen and the outdoor one. The coverage of the pergola, made of slim metallic planks, continues the main theme, adding to the image of the organized motion of streaming lines. Lecayet Pavilion The client of the next project, Alexander Lecayet, is a passionate collector of Soviet vintage cars, and an author of a number of books dedicated to this subject. The ground for his acquaintance, and later cooperation, with Stepan Liphart was the fact that the architect’s grandfather – Andrey Aleksandrovich Liphart – was for a long time the chief designer of the Gorky motor plant, and is one of the founders of the Russian motor building school. In 2015, Alexander Lecayet turned to Stepan Liphart with an idea of building a reception house with a hall for exhibiting vintage cars. The project of the pavilion was created with no reference to any specific location, on the verge of an architectural fantasy.  A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartOther things that influenced the project were the passion for the 1930s that they shared, and some expositional attitude. On the wall of the mansion, as a deliberate controversy, a Stalinist quote appears that Soviet Russia does not have to follow Europe, it is time to follow our own path. A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartThe Lecayet Pavilion consists of two parts: these are one and two-story volumes, interpreted by the architect as a leader and a follower, and if the concepts are coordinated with the theory of Ilya Golosov, as objective and subjective. In the single-story “subjective” unit, cars are displayed; the two-story “objective” one is essentially the space for “exhibiting” the master of the house, a place for representation and aesthetic pastime. The six stained glass windows resemble a six-column portico - because you need to give the private abode a dignified look! In accordance with its function (a house for grand receptions), the grand entrance of the pavilion is crowned with a peculiar detail: a balcony for addressing the guests; this tribune is accessed from the second floor, which includes a spacious master’s study with five-meter-high ceilings.  A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart A reception house and a private museum in Odintsovsky District of Moscow Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartAcropolis Litorinum Villa The conclusion of this series of projects - so far, the biggest one - is a sketch of a villa for the St. Petersburg partner of Stepan Liphart’s, a developer who bought a strip of land on the shore of the Gulf of Finland a few years back. The place is the high coast of the retreating Litorin Sea, a prehistoric reservoir, at the bottom of which significant coastal areas of the modern Baltic Sea were located, and the city of St. Petersburg as well. The terra cotta verticals of the pine trees, the slope, cascading down to nonexistent element, sea breezes, and sea skies brought to life the idea of a picturesque Acropolis. However, the context here does not just come down to the poetry of the sea. Right there, next to the trenches of the Great Patriotic War, the concrete foundation of the coastal cannon from the Mannerheim Line era was preserved, and the whimsical lines of old trees, which obviously experienced the destructive fire of the war, bear traces of battles. All of this, not without creative audacity, Stepan Liphart included in the imagery of the villa.  Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartAcropolises, just like the palaces of Roman nobility, were picturesque multi-component ensembles. This also influenced the structure of Acropolis Litorinum, consisting of three parts connected by galleries. On the west side, there is a tall “wing” of the master’s bedroom and library, which, when viewed from certain angles, looks like a ship with a mast and a captain’s cabin, reflected in stained glass windows. Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartThe glazed passage from the west gallery leads to the central part, turned with bent curves of its balconies and glass walls to the world and the sea. The verticals on the stained glass windows looks like the soundboards of some musical instruments. The plastique of the concave facades and their Art Deco nature display an homage to the Parisian palaces of the era of Expo 1937.  Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartThe west gallery has yet another peculiar feature: lined up along the architectural mote, its nonexistent facial supports are marked by the lines of the stained glass windows’ glazing pattern, which look as if they were marking the shadows of columns. The latter look almost weightless, but the capitels and the ebtablement still emphasize that these are supports, i.e. part of the order. In reality, the ceiling of the gallery rests on cantilever beams, and these, in turn, on pillars along the axis of the rear wall. The idea of the reflection of ethereal columns in the water of the trench is a technique in the style of “Reflections” by Debussy: the columns are already glass projections of themselves, and reflections of reflections appear in the water surface. Acropolis Litorinum. A private residence in Peski settlement in Lenongrad Region. Commissioned by a privaate client, 2015, not implemented.Copyright: © Stepan LiphartThe east gallery, running from the central part and bypassing the mote, directs one’s gaze to a small triumphal arch, which, at the same time plays the part of a sightseeing Belvedere. This, in turn, can be accessed by a staircase that essentially rises from the depth of the ancient sea, building a visual connection between the gone water, the firm ground, and the celestial spheres. In his yet-unimplemented villa projects, Stepan Liphart proposed a few elegant solutions in the Art Deco style, reinterpreted and continued in the contemporary. And, while the “hydroelectric power station” house is essentially a declaration of ideas, the ITR, Pavillon Lecayaet, and Acropolis Litorinum display the architect’s recognizable manner, which opens up new prospects for the future. |

|