|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 27.08.2021 | |

|

Alexander Balabin: “You must regard your every project as a chance” |

|

|

Lara Kopylova |

|

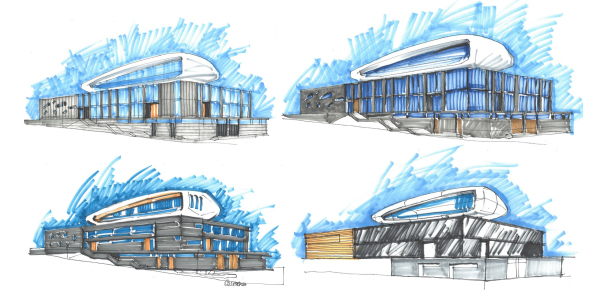

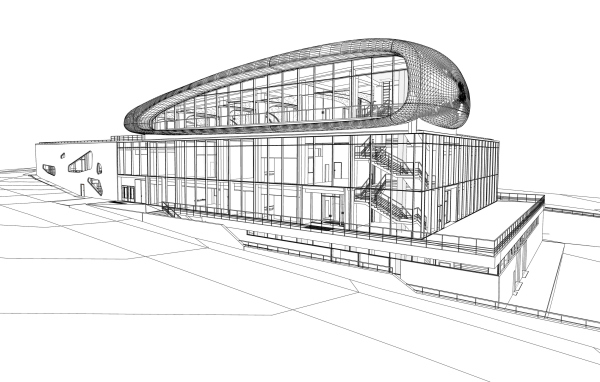

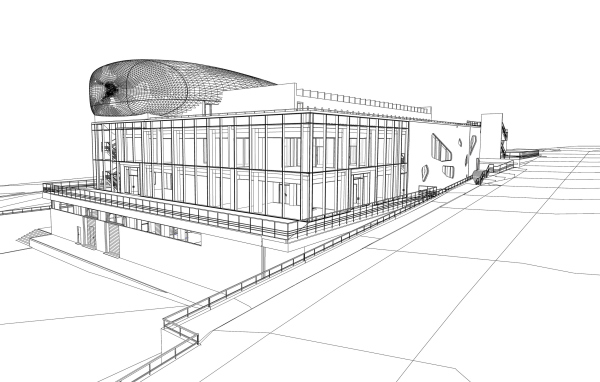

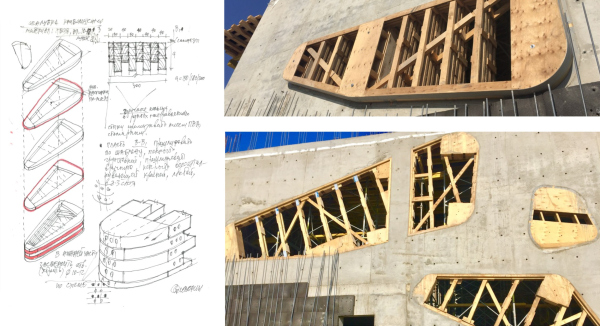

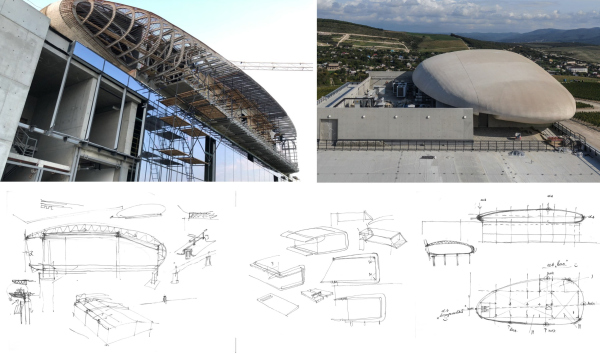

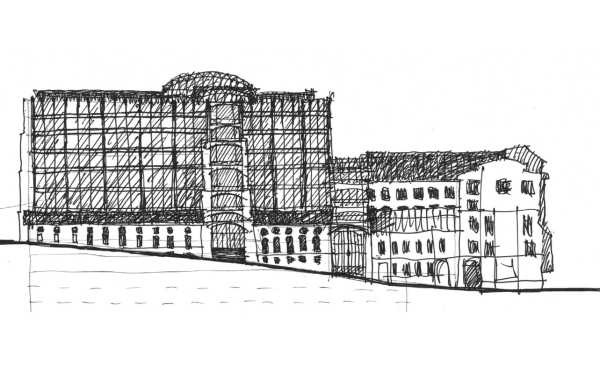

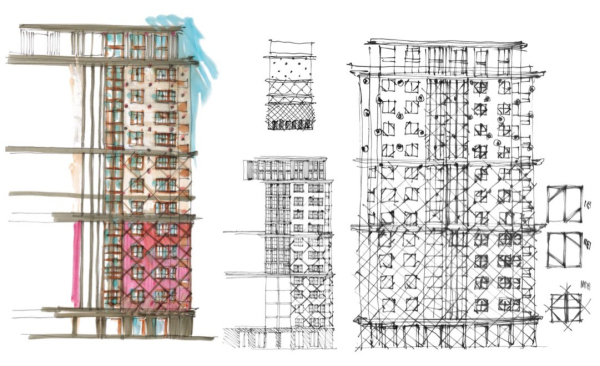

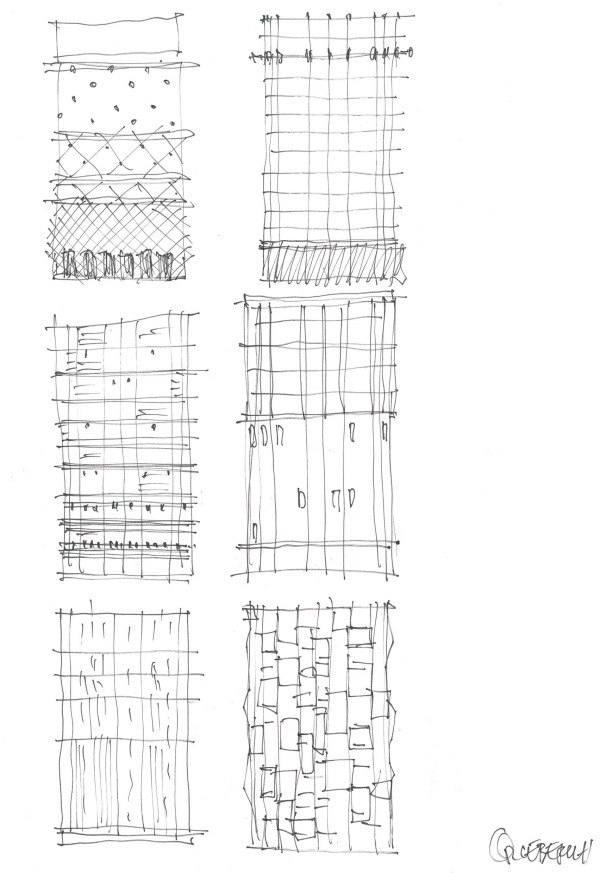

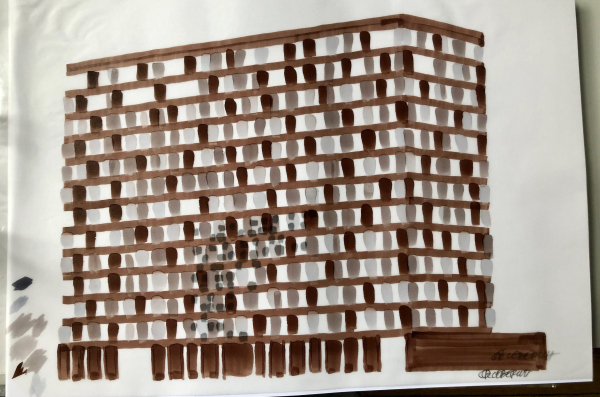

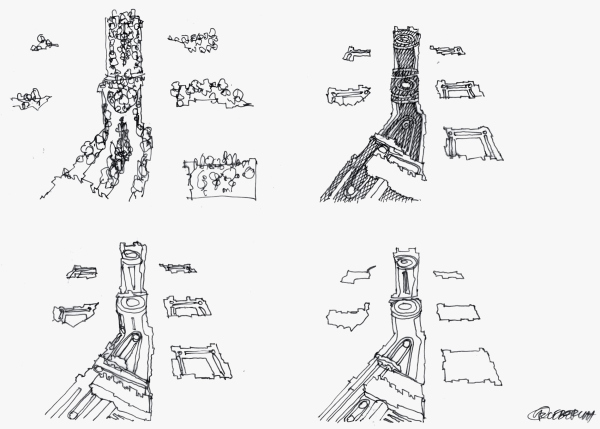

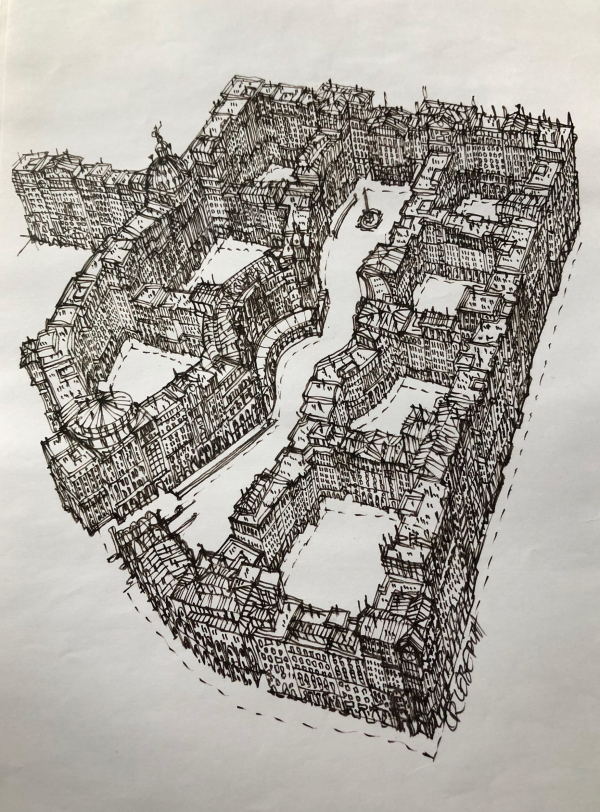

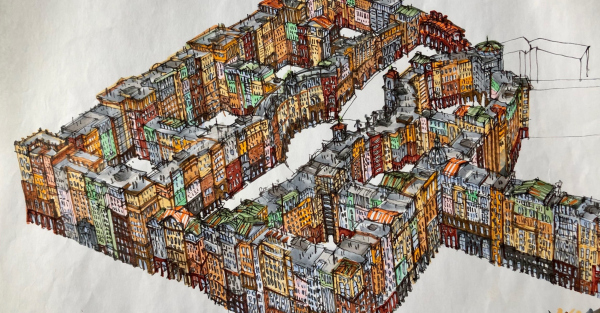

| Studio: | |

| Severin Project | |

|

The head of the company Severin Project, which has been successfully operating on the market for twenty years, is sharing about the history of his company, difficulties of landing big contracts, and about the creative chance that you must jump at. Your new project, the “Skalisty Bereg” (“Rocky Shore”) winery which you built in Krasnodar Territory, is already fairly popular; recently, it received the “Golden Section” award, and now it was shortlisted at WAF among implemented projects, which is a success by any standards. Can you name it the main project of your life? Your favorite?  You can make architecture either for love or for money. And, of course, it’s just great if the two coincide. The gravitational winery “Rocky Shore” is precisely the case. Our client wanted a powerful architectural statement. When they came to us in 2017, we laid out four options before them: the traditional Tuscan, German in the style of Bauhaus, technology-based Swiss, and North-Italian a-la Scarpa. And there was a fifth one, the most radical, which I drew just for myself – and this was the one that they went for!  “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright © Severin Project “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin ProjectCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project “Rocky ShorCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Projecte” wineryCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin ProjectI wanted to build it from real exposed concrete. At the bottom, where the production and storage facilities are situated, there is a brutal technological volume. At the top, where the tasting room is, there is a bionic shape that looks like a pebble with a cut edge.  “Rocky Shore” winery, the interiorCopyright © Severin Project "Skalisty Bereg« (»Rocky Shore") winery, the interiorCopyright: provided by Severin project “Rocky Shore” winery, the interiorCopyright: provided by Severin Project “Rocky Shore” winery, the interiorCopyright: provided by Severin ProjectThis was one heck of a story! The upper “pebble” part is actually a metal structure, upon which fiberglass reinforced concrete was stretched, like a frame. The rest of the building was built of monolithic reinforced concrete due to seismicity of 9 points. The lower part is architectural concrete in all its living glory, not covered up with anything. It took me a lot of time to draw up the sheeting maps. I made sure that the maps were of a certain size, that the fasteners were in certain places, that they correlated with the impost pattern, and with the horizontals too. For the window apertures in the shape of pebbles, we designed special binding, which was then made at a carpentry shop. And then we added aluminum frames that were inserted in the apertures without any stucco.  “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project “Rocky Shore&#Copyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project148; wineryCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Severin Project "Skalisty Bereg« (»Rocky Shore") wineryCopyright © Severin Project "Skalisty Bereg« (»Rocky Shore") wineryCopyright © Severin Project “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright © Severin Project “Rocky Shore” wineryCopyright © Severin ProjectWe are very happy that our project got much critical acclaim from the professional community, both in Russia, at the Golden Section festival, and at the international WAF, where, as is known, the selection is very strict. This is an important achievement for us. When and how did you decide to do architecture? According to the family legend, I’ve been drawing since I was five. I was born in Gorlovka in Donbas, then my family moved to Chernigov, where I finished high school. Then I entered the Odessa Engineering and Construction Institute, the architectural department. After my first year, I was going to go to the Budapest Design Academy as an exchange student. I came to check in at the military registration and enlistment office to settle a couple of formalities, and they said I was a draft dodger, and canned me there and then. So I unexpectedly did 3 years of navy service in Sevastopol. Then I decided to enter the Moscow Architectural Institute. I was introduced to the head of the drawing department. For two months, I would practice nine straight hours every day, not standing up from my easel for a minute. Then I scored an “A” at the entrance exam for drawing a head. And, since I finished high-school with a gold medal, and the first year of the Odessa Institute with honors, I was at once taken to the second year of Moscow Architectural Institute. I was really lucky because I got into the group led by Boris Barkhin. This group consisted of brilliant students because they were mostly the children of architects: Aleksey Ginzburg, Alexandra Gutnova, Ilia Voznesensky, Evgeny Raitsis, and others. During my last year in Moscow Institute of Architecture I went to study in Great Britain for half a year as an exchange student, and, after I got back, I defended my diploma project. How did your career develop? Which project do you consider to be the milestone for you as an architect? Immediately after graduation, in 1993, I founded my architectural company and designed interiors and furniture – we even made furniture ourselves. It was not until 2000 that I started doing big time architectural design. I can’t boast too many projects that were 100% made by my design. The first important project that was implemented really close to my original design was the reconstruction of the former EMO Factory in Nikolo-Vorobinsky alley for the office of RAO UES. Currently, the Tessinsky 1 housing complex is being built in that same place, designed by Sergey Skuratov. Our project was a reconstruction one, and it covered two buildings in the Tesinsky Alley: a Soviet one from the 1970s, and a building of the 19th century – it was a difficult one because it was built up many times. We kept the original brick vaults and the Mognet vaults, even though we did not manage to do the brickwork repair that we originally planned – the facades were just stuccoed. We made these buildings into an office center, and it successfully operated for almost 10 years.  A-Class office center designed for RAO UES. Project, 2009Copyright © Severin Project The A-class office center for RAO UES, a sketchCopyright: provided by Severin ProjectAn office building in the center of Moscow… a pretty good start! On the whole, your portfolio includes more public buildings than housing projects. Is it by chance or by design? Both. Public buildings always seemed more interesting to us. We were lucky to land a project of Russia’s first multiplex in 2001, a 4-hall multiplex KARO-1 in Auchan on Sheremetyevskaya Street, and movie theaters became a trend with us. We designed more than forty movie theaters all over Russia: from Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk to Nadym; in all Russian cities with a population of over one million, we have designed more than 400 screens (usually, a movie theater has from 4 to 11 screens). We worked with all major networks: Karo-1, Karo-2, Formula Kino and so on. Over the last twenty years we have created many projects of public facilities: shopping and entertainment centers, movie theaters, hotels, and many restaurant chains. In 2005-2008 we developed the concept of the Goodman steakhouse, Filimonova and Yankel restaurants, Aligato, Shokoladnitsa, and others. Our special pride is the Center for Active Longevity that we designed and built in Malakhovka. This is a new type of nursing home, supplemented by a neuropsychiatric unit for old people with memory problems. Of course, it looks nothing like those houses of sorrow that have remained from the Soviet era. We thought through the ergonomics down to the smallest detail, drew 15 types of housing placement, of which we then chose the most optimal one.  A boarding school of general type with a neuropsychiatric departmentCopyright © Severin Group A boarding school of general type with a neuropsychiatric departmentCopyright © Severin GroupSo why did you decide later on to do housing projects as well? After 2014, it became possible to do good housing architecture – and not just in the luxury segment, like, for example, in “Golden Mile”. And I wanted to do large-scale projects. But it was clear to us that we had to enter the market not from the front door (i.e. with concepts) but through the back door (i.e. with working documents). Our first work of this kind in Moscow was a contract with Strabe for DONSTROY for adjusting the project and developing working documents for the housing complex “Zhizn na Plyushchikhe”, 56,000 square meters, completed in 2014. This was our first contractual project in BIM, even though we began implementing BIM as early as in 2007. Then we signed a contract with the company “City 21st Century” for designing the “Rafinad” housing complex in Khimki. It was 100,000 square meters big. Before we came around, five different architects were doing concepts for this site because the head of the developer company, an Orthodox Church member, and a Greek by birth, was endlessly trying to achieve perfection. We passed three stages of approvals with him. In Rafinad, we partly did the conceptual proposal, and a full-scale design development phase, working documentation, and the architectural and city development phase. Parallel to that, we won a competition for the concept of the concept of the tower “Schastye na Lomonosovskom” for the company Leader Invest, which was part of AFK-Systema; that concept was fully developed by us. Every time we started working with an investor, we had to go through a lot of hard and unpleasant work. For Leader Invest, we first agreed to adjust the project and the working documentation of the house on Usievicha Street. Then we were confronted with a difficult situation. We passed through two gruelling approval sessions and completed the working documentation – and ultimately the house was built. After that, we won a tender for working documentation for the Lomonosovsky, and now the Schastye tower is almost ready.  “Schastye na Lomonosovskom” housing complex, the projectCopyright © Severin Project “Schastye na Lomonosovskom” housing complex, the projectCopyright © Severin Project “Schastye na Lomonosovskom” housing complex. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright: provided by Severin Project “Schastye na Lomonosovskom” housing complex. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright: provided by Severin Project “Schastye na Lomonosovskom” housing complex, the projectCopyright © Severin Project “Schastye na Lomonosovskom” housing complex, the projectCopyright © Severin ProjectParallel to that, FSK-Leader invited us to work on the housing complex “Dvizhenie” (“Motion”) in Tushino, 106,000 square meters. We did the design development phase and the architectural and city development phase, then we won the tender for developing working documentation. This complex, consisting of three 22-story buildings and a 13-story one, is all but completed. On that project, we were faced with difficulties of purely legal nature: the owner is Tushino-2018, i.e. Spartak, and FSK-Sistema is both investor and developer.  An apartment complex within the bigger complex “City on the Tushino River 2018”. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright © Severin Project An apartment complex within the bigger complex “City on the Tushino River 2018”. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright © Severin Project An apartment complex within the bigger complex “City on the Tushino River 2018”. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright © Severin Project An apartment complex within the bigger complex “City on the Tushino River 2018”. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright: provided by Severin Project An apartment complex within the bigger complex “City on the Tushino River 2018”. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright © Severin Project An apartment complex within the bigger complex “City on the Tushino River 2018”. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright: provided by Severin Project An apartment complex within the bigger complex “City on the Tushino River 2018”. A sketch by Alexander BalabinCopyright: provided by Severin ProjectIt turns out that if you want to land a decent contract, you have to work like Jacob did for Rachel, for several years. Today, you have large-scale housing complexes in your portfolio, even giants. Can you please share about the “Roman Quarters”, and how the authorship was divided there? We landed a commission to do the 3rd stage of Roman Quarters for FSK. Mikhail Filippov created a concept for all the three stages. Then he did the design development for the first stage – and this is where his collaboration with the client ended. Then other architects did something else based on his concept. We had a task of fundamentally revising the concept, and increasing the output of useful floor space, which led to the overall area of the 3rd stage being 365,000 square meters. We gave our answer to the question what Roman Quarters must look like. The answer from Mikhail Filippov is more ensemble-like, more hierarchical. As for us, we tried to recreate the multiple overlapping levels, which are typical for Rome, this kind of uneven construction with a broken redline belonging to different epochs. Just think: there is a ruin from Antique architecture, then it gets overbuilt by the Barbarians. Then medieval castles appear, which are covered by Renaissance galleries later on. I even threw in a couple of modern facades. As a result, Stage 3 is already in construction. Too bad they “cut down” our ruins when we were getting the “city and architectural image” approval.  “Rimsky” housing complex (Stage III), the projectCopyright © Severin Project “Rimsky” housing complex (Stage III), the projectCopyright © Severin Project “Rimsky” housing complex (Stage III), the projectCopyright © Severin Project Rimsky (“Roman”) housing complex (Phase III), a projectCopyright © Severin Project Rimsky (“Roman”) housing complex (Phase III), a projectCopyright © Severin Project “Rimsky” housing complex (Stage III), the projectCopyright © Severin Project Rimsky (“Roman”) housing complex (Phase III), a projectCopyright: provided by Severin ProjectThe complex consists of buildings that have a varying number of floors, which has to do with insolation. The yards are situated on stylobates. People go for walks on the upper level. All the vehicles, except for emergency ones, drive on the bottom level. There was yet another problem that we had to face: a chunk of land with a pipeline was alienated, and we had to provide the stipulated technical and economic performance on whatever land we had left. And we “squeezed” out of it 190,000 square meters of apartments alone. The client, however, did not appreciate our effort. Besides, they changed the subject of the contract several times. This was challenging work but we managed. Nobody before us did. Speaking of challenging projects, I want to ask you how you deal with clients? How do you organize your relationship? What problems do you have to face? Lacunae in legislation, and the absence of a single legal base for clients and architects oftentimes invites escalation of conflicts. While in construction you can submit your project in milestones (you close your volume and your materials with a control certificate and get paid). In the field of design, however, it is the working documentation that is considered to be the volume of work; 365,000 square meters is a truckload of project documentation. But until a positive expert opinion is signed, you cannot receive a signed act. As a consequence, you are “hanging” in advance payments. They can tell you: we don’t want your work, we are dissolving the contract. They may find issues, however small, like a comma in the wrong place, and refuse to accept your work. There is a good saying: “If you’ve made use of somebody, this does not mean that you’re smarter. What it means is they trusted you more than they should have.” The fact that the rules of the game are so vague creates difficulties for everyone. Hence, we want to work with more “quality” clients. You do both traditional and modernist architecture. Where did you learn historicism? You learn things that are interesting to you as you go along. I look around and I see what this or that thing is made of. In addition, I have a huge architectural library – a 9x4 wall with bookshelves. I examined the architecture of orders several times. The first time it was when I designed a hotel in the form of a small palazzo for Almaz-Antey on the Ivankovskoe Highway. I perused my books in search of the rhythm of windows and cornices. I drew about 200 studies in the process of searching for the right facade design. I studied proportions using a Palladio book. I realized that I could not use them in full effect because I would then have to change the dimensions of the building, but some of them I did use. Another project that was very interesting to me was a fitness center on Marshala Rybalko street next to Marshal housing complex designed by Mikhail Filippov. Burov, for example, when he was studying Brunelleschi, tried to understand the proportions of arches in order to keep up their “elasticity” on the facade of the Central House of Architects. I also invested a fair amount of time, only I did not exactly calculate, but drew the rhythm of the arch belts, until I found the right proportions. It was a bright and resonant thing but they did not finish it.  Maeshal housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Alexander Balabin The Marshal housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Alexander Balabin The Marshal housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Alexander Balabin The Marshal housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov The Marshal housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov The Marshal housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Daniel AnnenkovWhat was your role in designing the Wine House complex? Our part in this project, which was done for Gals Development, was the former Smirnoff warehouses, which later hosted the “Cornet” factory. The case required reconstruction, restoration, and new construction. We kept the Mognet vaults and the perimeter. Down below, where there are the vaults, we placed a restaurant, and further up the apartments. Later on, we designed for the same client a rugby school in Zelenograd, and a kindergarten within the Nasledie complex.  Winehouse housing complex. Luxury LoftCopyright: Photograph © Archi.ru Winehouse housing complex. Luxury LoftCopyright: Photograph: Archi.ru Winehouse housing complex. Luxury LoftCopyright: Photograph: Archi.ru Winehouse housing complex. Luxury LoftCopyright: Photograph: Archi.ru Winehouse housing complex. Luxury LoftCopyright: Photograph: Archi.ruAs far as I see, Severin Project has a large functional scope, from shopping centers to housing projects and schools, to nursing homes and transport facilities… We are not scared of taking on new challenges. We love making sense out of functional diagrams. Then breathe life into architectural forms. We did the design development phase of a huge shopping mall for Hines Development, almost 300,000 in the vicinity of Vnukovo. But in 2015 the American investors left. Before that, it was a shopping mall in Vidnoe, 110,000 square meters big. We also did a lot of projects for Russian Railways. At their commission, we examined all the 1,500 suburban stations of the Moscow Railroad. We did the analytics, prepared a project, and reconstructed 26 stations. One of them, Ochakovo, I designed myself, and it turned out to be a great one. We also did flowcharts for Transport Interchange Hubs. But it was a closed-door thing, and the company, with which we cooperated, did not win. We also did a reconstruction project for the railway station in Sergiev Posad, and a reconstruction project for a tea-packaging factory. Tell me how your company is wired. What number of coworkers do you need to cover such a tremendous scope of tasks? In 2004, I reorganized my company into Severin Group. There were four companies with different partners: Severin Project, Severin Design, Severin Group, and Severin Development. Severin Development essentially performed the function of the technical commissioner in Moscow. We were more known as a technical commissioner, and less as a general designer. A year ago, I sold my shares in all of the companies, save for Severin Project and Severin Design. Now I am focused solely on design. We had 146 employees at the peak. There were 40 architects, 40 designers, and engineers of all specializations, because we do all sorts of working documentation. Plus accountants and couriers. Now we had to cut our staff because of the pandemic. Today, we chiefly finish current projects, new things remaining in the concept phase. What does the word Severin in the names of your companies stand for? My great-grandfather, the Cossack Ivan Logvinovich Severin, was a cabinetmaker. I named my company after him. What would be your advice to young aspiring architects? I am now teaching a management course in architecture at the Institute of Business and Design. I tell students that any project must be regarded as a chance. Life is short, and the professional age of an architect is only 20-25 years of actual activity. You graduate at twenty-five, and the light in your head comes on about ten years later, when you can design a project from beginning to end, fully grasping it with your mind, being at the peak of your mental clarity. You really start off at thirty-five, and you must manage to do something before you are sixty. This means five or seven major projects. This does not mean that you will not have any work after that – you will. But such projects that are really worth it, and you have rapport with your customer, will be few and far between. This is important. I was really lucky with the “Rocky Shore” winery. This is one in a million. Nobody ordered a masterpiece. But the very shape of this building must become – and already has become – part of our brand. And the winery itself turned into a regional landmark. |

|