|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 05.04.2021 | |

|

Sergey Skuratov: “A skyscraper is a balance of technology, economic performance, and aesthetic appeal” |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Sergey Skuratov | |

| Studio: | |

| Sergey Skuratov architects | |

|

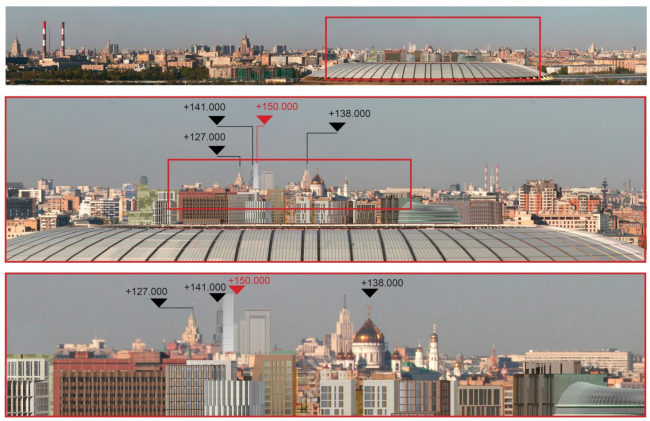

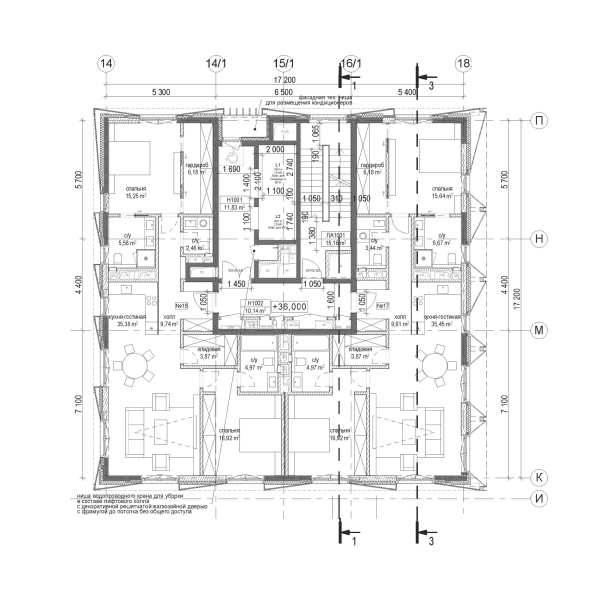

In March, two buildings of the Capital Towers complex were built up to a 300-meter elevation mark. In this issue, we are speaking to the creator of Moscow’s cutting-edge skyscrapers: about heights and proportions, technologies and economics, laconicism and beauty of superslim houses, and about the boldest architectural proposal of recent years – the Le Corbusier Tower above the Tsentrosoyuz building. Archi.ru:  The multifunctional high-rise residential complex within Moscow City. The top elevation mark is 442.8m, 2019Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The multifunctional high-rise residential complex within Moscow City. The top elevation mark is 442.8m, 2019Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSThe building echoes the narrow elongated site; it is beveled like a blade from the side of the Third Transport Ring, the width of the “sharp edge” being 2.4 meters, yet, when viewed from a distance on this scale, it does look like a blade. If we are to look from the Kamushki district, the tower looks more like a sail or a wing – but here everyone is free to make their own associations. It would be a really good thing if we were able to keep the silk printing on the facades – because on the facades we have a white gradient, and, interestingly, on the lower office floors it covers more of the surface, while higher up, where the apartments begin, it gradually disappears.  The multifunctional high-rise residential complex within Moscow City. The top elevation mark is 442.8m, 2019Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The multifunctional high-rise residential complex within Moscow City. The top elevation mark is 442.8m, 2019Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSWe even had an idea to pull the height up to 465 meters – and then the pure height of the tower would be even greater than that of the Lahta Center, including the spire [the total height of the Lahta Center is 462 meters, and 365 meters not counting the spire – editorial note]. However, when we made calculations, it turned out that these extra 20 meters make the construction significantly more expensive because they entail an extra technical floor and extra requirements for the building’s foundation, and we gave up on this idea. We even debated using metallic bearing structures but it would take forever for the metal to arrive, and we had to settle for reinforced concrete with soft metalwork. Thus, it turns out that the highest centerpiece of the Moscow City occupied the narrowest site on its edge... Actually, the site is rather advantageous because two Krasnogvardeysky drives meet here, and it looks great from the Third Transport Ring, its profile standing at its thinnest. A great place for a vertical!  The multifunctional high-rise residential complex within Moscow City. The top elevation mark is 442.8m, 2019Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The multifunctional high-rise residential complex within Moscow City. The top elevation mark is 442.8m, 2019Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSBut then again, of course, it’s always better to build from scratch because on a new territory you have a chance to think everything out and put the tallest skyscraper in the most beautiful place, that is, in the center, designing a plaza and an esplanade around it... Getting back to the City – recently two of the three of your Capital Towers were built up a a 300-meter elevation. In the original project, just as ONE Tower, they weren’t quite that tall, were they? At first, they were 200 meter high, then I proposed 250 meters, then we were able to raise them to 272; after that, when it became clear the apartments were selling really well, we increased the height by another 10%.  Capital Towers on the Krasnopresnenskaya Embankment, 03.2021. View from the southCopyright: Photograph: Archi.ru Capital Towers on the Krasnopresnenskaya Embankment, 03.2021. View from the westCopyright: Photograph: Archi.ruWhich construction stage are you at? The two towers are completed up to the top, and their interior decoration is nearly complete. The third one, which was started first, by the way, is lagging behind, but such things do happen... We still have to do the interior decoration, the stylobate part, the landscaping – a lot of work to do, in short. How many high-rise projects are you currently doing totally? About ten, but I cannot give you the exact figure because some are just beginning, and some, on the other hand, are suspended. Recently, we completed and presented a competition project of a housing complex in the northwest of Moscow, which, among other things, has two towers. One is 250 meters high, the other is 150. We are expecting the results now. We are also conducting negotiations with a new client about designing new housing complexes in Moscow’s north and in Nizhny Novgorod. We are doing several master plans with pre-concepts in Moscow. We are also drawing a couple of skyscrapers in the southeast: three towers, two 240 meters high each, and one 150 meters high. The paired towers have a shape unusual for Moscow, with an undercut at the top and at the bottom, and with a public terrace at the 200-meter height. The corners of the towers are rounded, but, wherever there is a cutoff, they are straight, is if wood was cut by a blade with new offshoots leaning towards the sun... Recently we, together with another client, tried to change the high-rise silhouette of one of the buildings of the housing complex on the Fonchenko Street. The one next to the Poklonnaya Hill? Which of the houses did you build up? The corner one, which is the closest to the metro station. The idea is now being discussed by the city authorities. The chief architect seemed to like it. But the final decision is up to the mayor. Furthermore, we proposed to make a restaurant in the upper tier there, with a very high space over it, 6 meters high: there are walls on two sides, a glass wall that protects the guests from the noise of the railways, and a glass wall 3.5 meters high overlooking the park. It must really be great there in the summertime. Restaurants on top floors with panoramic views, as a rule, enjoy a fair bit of popularity – I remember there was one next to my office on Novokuznetskaya... However, I think we pioneered a restaurant on such a height and with so much space. I did research on the subject but I did not find anything like it. Our client liked it. Now you tell me why I can’t build a tower here! I will not! In this instance, Moscow City is right at hand, and the Poklonnaya 9 housing complex is being built nearby, no less than a hundred meters tall, the obelisk of the museum on the Poklonnaya Hill is 145 meters high, and there are other towers around. And how are things with your most discussed skyscrapers, the one on the Sakharov Avenue, next to Tsentrsoyuz? At what stage is the discussion? Still “at the stage of discussion”. We made several options – 125, 150, 175, and 200 meters high. The first option, 125m, was coordinated with the size of the long Tsentrsoyuz building. On the whole, it was devised as a monument to Le Corbusier, and his memorial museum. The exposition was to be placed in its stylobate part, with an entrance through the city square, one floor lower than the street level. It also has a buildup with a sightseeing platform, which, if this project comes to fruition, will command a breathtaking view of the Tsentrsoyuz building from a bird’s-eye view: nobody ever saw it from this angle. This place would be great for virtual demonstrations, for example, you could superimpose the “crosses” of the Voisin plan on the real panorama of Moscow. The multifunctional complex on Myasnitskaya StreetCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSThe very imagery of the tower echoes the time of Corbusier: a very simple volume, glass and metal – and the inevitable metallic pillars, light and slender, combined with curvilinear glass corners in the spirit of Mies van der Rohe or Frank Lloyd Wright. To ensure the privacy of the apartments, we are planning to use light-reactive electrochromic glass: you enter the apartment, turn the lights on, and the windows become milky white so that the inside of the apartment is invisible from the outside [shows a sample of glass, flips the switch, the glass does work]. When you turn the light off, the glass becomes transparent.  The multifunctional complex on Myasnitskaya Street. Vew 3 from the Akademika Sakharova Avenue. The 150m versionCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The multifunctional complex on Myasnitskaya Street. View 6 from Myasnitskaya Street. The 150m version.Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSOn your website, I saw still another version, 58 meters tall. Is it within the maximum allowed elevation? The one that looks like the Tower of Babel? Yes, I did ask my colleagues to draw it just to see what it might look like. The Cultural Heritage Department of Moscow is ready to approve it, but I frankly dislike it – even if they do ultimately approve it, I will not build it. Where did the idea of this tower come from? Was it you or the client who proposed it? The client approached us with a task of building mere 16,000 of ground-level floor space in the stead of two dilapidated average houses built in the early XX century. The tower was proposed by me, and I am sure that here it is more than appropriate – it will become a landmark of this place. We as human beings need verticals on a city – they mark the space, and you can climb them to see the city for miles around. Back in the day, Moscow had “forty of forties” of churches with belfries, then the first high-rises appeared – and I cannot recall anyone having anything against them... And we admire them even today. Boulogne, France, also has a lot of towers in it. Besides, the very environment of the Sakharov Avenue was formed in the XX century; it was formed as part of the “new Moscow” with other towers designed there as well; my tower may become the final accent, like a stele commemorating Le Corbusier. All the architects, to whom I showed this project, liked it – Yury Volchok spoke very much in its favor. When I showed it at the council of the Cultural Heritage Department of Moscow – experts, city administration officials, and architects – everybody was supportive of this idea. The mayor and the chief architect of the city, Sergey Kuznetsov, also like this project. But everyone is afraid to create a precedent. And what do you think about creating a precedent of building a tower within the Garden Ring? My opinion is that a precedent is nothing – you need to consider specific instances and specific proposals. They say: if we allow it here, then everyone will start building skyscrapers in the historical center. But what do you specifically mean by “everyone”? If somebody does design a good skyscraper appropriate for this specific location, why not build it? Go ahead and create some kind of a council that will consider such “exceptional” cases – I am personally quite ready to become a member of it. Ultimately, it’s up to the city administration to allow or not allow this to happen. But the point still holds – you need to consider the value of each specific proposal, and not be afraid of “towers in general”. If you as an architect, without any external pressure exerted on you, realize that you can build a beautiful building here – why not build it? There are, of course, people out there who don’t want anything to change at all. But then what will remain of our time? Nothing but compromises? The last thing you want to do is turn the city space into some kind of sacred cow – you cannot freeze it one and for all. What you can do, however, is make sure that it changes for the better. The city must keep on changing, but the vector of these changes is dependent on specific circumstances, talented architects, developers who are not afraid of experimenting, on the public mood, and on the goodwill of the city authorities... I try to design landmarks that are as slender, graceful, and unobtrusive as possible, although they do alter the skyline, of course. But then again, I believe that even if a dozen ultra-slim skyscrapers appeared within the Garden Ring, the city panorama seen from the Sparrow Hills would not really change all that drastically. The multifunctional complex on Myasnitskaya Street. View from the Sparrow Hills. The 150m versionCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSHowever, you can build a super-slim tower only downtown because it’s pretty hard to implement from the point of view of its economic performance – for example, because the elevator will only be seeing one apartment on each floor, to name but one reason. On Myasnitskaya, may useful / served floor spaces ratio was 1:2, and this is a pretty expensive solution, which can only be in demand in the center of Moscow. Generally speaking, a super-slim skyscraper is a purely New York invention with very expensive land, a reliable rock-steady foundation, and amazing financial capabilities of buyers: there are people there who are ready to pay $150-200K per one square meter. In Moscow, it’s much harder to find the optimal balance between economics and technology. Even though I did build at least one super-slim tower in Moscow already. That being? The high-rise building of the “Medny 3.14” residential complex on Donskaya Street. Its height is a little over 100m, its construction thickness is 16.8m, and the outer contour dimensions of its base are 18x18m. Two apartments per floor.  The housing complex Medny 3.14Copyright: Photograph © Daniel Annenkov, 2021 Plan of the east tower, the highest one. The housing complex "Medny 3.14"Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSAlmost each of the projects that you mentioned increased its height in the course of the design process. Do you increase them for aesthetic reasons, in order to get slender proportions? Or for purely economic ones? First of all, for the sake of proportions. Starting from a certain height, a tower benefits from having a slender silhouette, the thinner the better. Getting return on investment is where it gets hard – everyone knows that any developer is happy when you give them extra floor space that they can sell. And here we find ourselves in a fork between the price of technical solutions, which rises together with the height, increasing the construction costs – and the purchasing power, a market that in Moscow is far from providing such opportunities as in New York. A skyscraper is a balance of technology, economic performance, and aesthetic appeal. Let’s take “Medny 3.14”, for example – if, given the base was still 18x18m, the tower were not 100, but 200 or even 250 meters tall, the construction cost would grow by half. But the market prices would stay the same! This is why we limited ourselves to 100 meters, even though the city would have permitted an even greater height in this place. And a 300-meter skyscraper with an 18x18m base can only be built in New York. Therefore, convincing the developer to build a super-slim tower is a pretty hard task because the height must be economically justified. But when we make our calculations, we calculate the economic performance as well, we can handle that. The apartments in your towers – are they primarily designed for limited-term stays or for permanent residence, meaning – are these towers essentially housing projects? Chiefly housing projects, with all the encumbrances proceeding from it. We pay a lot of attention to the public functions in the stylobate part, which becomes particularly important with this housing density. How exactly does the price go up as you increase the height? What are the factors? Lots of factors. Glass facades with good profiles and hidden imposts are very expensive. Or jumbo coated glass – a modular facade with a 3.6x1.2m pitch is also an expensive solution. A lot depends on the soil, the foundation, and the wall thickness; for example, the “bucket in bucket” solution requires much more concrete for the intermediate floors than pylons perpendicular to the facade with a pitch that matches the width of the rooms – this last solution gives you less freedom in term of planning or facade design but it significantly cuts the construction budget. As the height increases, new mechanical floors inevitably appear, and the cost of the engineering equipment and services also gets more expensive, because you need to supply water, air, and electricity to these high floors. Plus consider the wind load. When do wind loads become structurally critical? For towers starting with proportions of 1:10 and slimmer. The Capital Towers have a width/height ratio of 1:14.5, ONE tower – 1:15. Incidentally, we are planning to test its model for wind load resistance soon. We check all our high-ride projects several times in a wind tunnel, weigh them with sensors and “blow through”, finding and strengthening their problem areas. What size are the models that you test? About one meter and a half or two meters high. But, of course, as the leader of the company, I do not delve into all the details – the engineers and the chief architect of the project do that. The chief engineer of most of the towers that we build is Mikhail Kelman – the bearing structures are his area of responsibility. I am more concerned with the aesthetics, the typology, and how the construction influences the building’s image. As far as I see, the shape of your towers rather gravitates towards simplicity than complexity. How would you describe your perfect skyscraper? I am the advocate of laconic architecture – these bright “ultra-fashionable” things grow outdated just as quickly. Towers must be pristine, graceful, and very simple – they grow up like trees without branches. This is one of the specific features of this typology: all the public life is grouped at the bottom, in the lower tiers, complex, with height drops, depressions and protrusions. Down below, there are lots of details and diversity, both spatial and emotional. As you go higher, however, you don’t need anything- it’s just technology, and the facades only serve as a shell. The upper and lower parts contrast with one another, and I always try to highlight that contrast. But then again, there is also a downside to a laconic shape – it’s very hard to come up with a new move that would nicely fit the construction economics, safety requirements, combat overheating and overcooling, the danger of icicles formation, and, specifically, the safety of people waking down below. Your very first skyscraper, the residential tower on the Mosfilmovskaya Street – I would not describe it as laconic. But, as far as I remember, even there you had to simplify the spiral twist? I did not “have to” – it was my independent choice. I needed to turn the views from the apartment windows in the direction of the city center, and I kept meditating on it until it just dawned on me: I literally took a piece of foam rubber and twisted it. That was it! Many people compared that “undertwist” of mine with the Turning Torso is a neo-futurist residential skyscraper in Sweden and the tallest building in Scandinavia, but when I was designing my tower, I didn’t even know about it. And this faceted shape turned out to be the optimal one. But the house on the Mosfilmovskaya Street appeared under quite different economic conditions, the economic situation was on the rise, the construction cost was lower, and I had a task to design something really flashy, money no object. This is why you can see there our trademark columns of brick concrete, the “braided” pattern in the second unit, and many other embellishments. Sadly, the second pair of buildings was not eventually constructed – it was planned to be the same but reverted at a 180-degree angle, and, also regretfully, the park did not appear. What did appear were a few new buildings surrounding my prize creation, which, in my opinion, are totally inappropriate. Why do you think apartments in skyscrapers enjoy such unfailing demand, even in spite of the fact that they are far more expensive? Skyscrapers are a complex but still a global phenomenon. On the one hand, they are a direct consequence of technical progress, new technologies, and the increase of the cost of land in megalopolises. Among other things, they help to make the size of the city more compact, stopping it from sprawling in all directions. On the other hand, they have to do with the appearance of the social group of people who literally wanted to live “above everyone else”, like the Lannisters in “Game of Thrones” in their stronghold overlooking the city. Different cities react differently to this trend: in Paris, all towers are collected in the La Defense area, and in London they appear everywhere – although also only in those areas that are well suited for economic reasons. By the way, I will note that a few years ago, while walking with my eldest grandson in Kensington Park, I saw that the tower of The Shard by Renzo Piano marks the axis of London parks amazingly well. Towers make excellent accents if they are positioned correctly – in this sense, they “work” with the space of the city as a whole, compartmentalize it, and attract the eye. If they are well designed, of course.  The house on Mosfilmovskaya StreetCopyright: Photograph © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The house on the Mosfilmovskaya StreetCopyright: Photograph © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS |

|