|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 15.10.2020 | |

|

The Contact |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

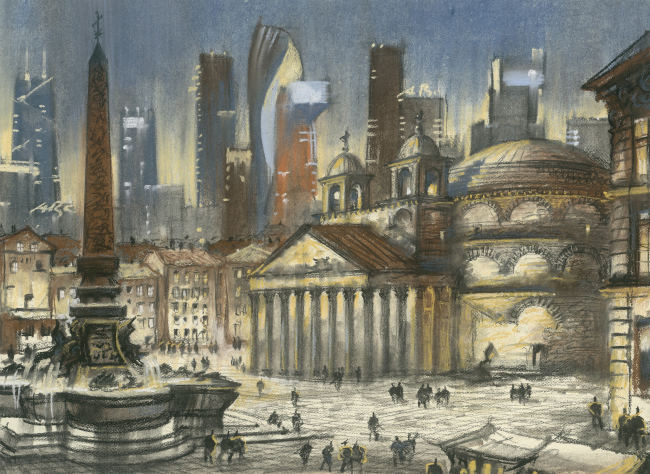

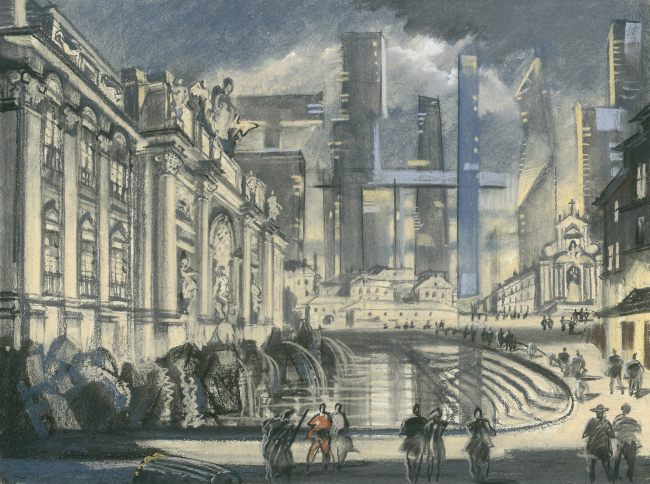

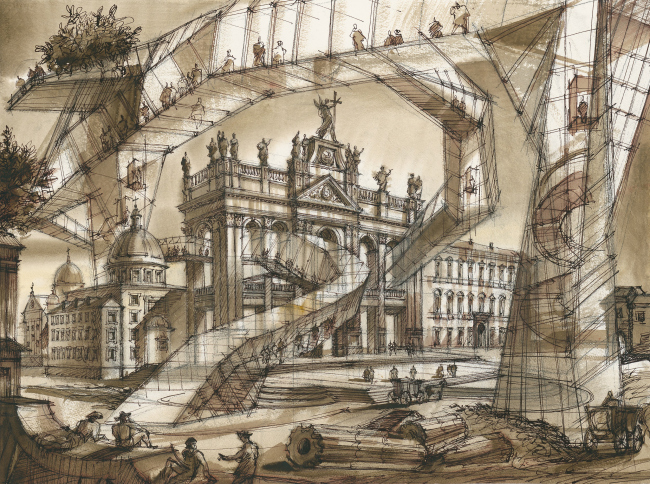

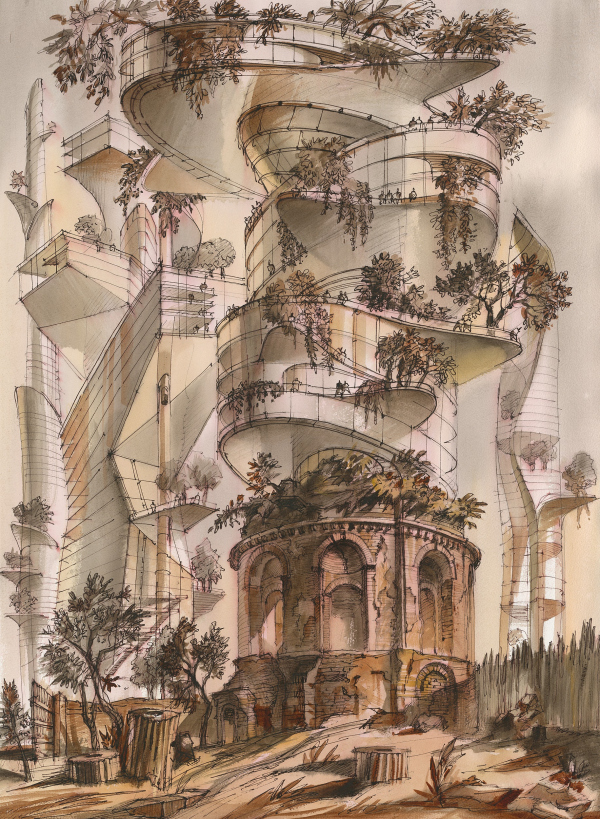

| Studio: | |

| Tchoban Voss Architekten | |

| SPEECH | |

|

The Istituto Centrale per la Grafica in Rome presents Sergei Tchoban’s exhibition “Imprint of the future. Destiny of Piranesi’s City”. The exhibition includes four etchings, based on Roman architectural views of the XVIII century complemented by futuristic insertions, as well as a lot of drawings that investigate the same topic, at times quite expressively. The exhibition poses questions, but does not seem to give any answers. Since going to Rome is pretty problematic now, let’s at least examine the pictures. The Central Institute for Graphics is situated on via della Stamperia, i.e. “Typographic Street”, next to the Trevi Fountain Square, 3 minutes’ walk from Corso, right across from the Roman Academy of St. Luke. It is quite a cozy tourist place that has a pleasant atmosphere of this classical city, built largely in the XVII and XVIII centuries, but on the remains of the times of Octavian August. Thus, it comes as no surprise that the place for the exhibition of Sergei Tchoban, timed to coincide with the 300th anniversary of Piranesi, was found in this location. The exhibition is co-organized by the Central Institute for Graphics and the Museum for Architectural Drawing in Berlin (Tchoban Foundation).  The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching "Veduta dell esterno della Gran Basilica di S. Pietro in Vaticano"Copyright: The etching was made by Ioann Zelenin by Sergey Tchoban′s drawing The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Veduta della Piazza di Monte Cavallo”Copyright: The etching was made by Ioann Zelenin by Sergey Tchoban′s drawing The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Veduta della Piazza Navona sopra le rovine del Circo Agonale”Copyright: The etching was made by Ioann Zelenin by Sergey Tchoban′s drawingAll of the four cityscapes: Piazza Navona, Quirinal Hill, the Arch of Septimius Severus at the northwest end of the Roman Forum, and St. Peter’s Cathedral are the classic architectural views by Piranesi. These buildings have glass forms inscribed into them; in two cases, they look like long overpasses and giant cantilevers; there is a semblance of the Moscow City towering from behind the Quirinal Hill, yet with more complex shapes than usual, while the Arch of Septimius Severus is overshadowed by a cross between a skyscraper and a sightseeing platform. These four images, which depict Rome of the XVIII century in the etchings of the famous master – as much classicist as he was a romantic, one of the most heart-felt, and, hence, one of the most famous artists who portrayed architectural views – clash with the forecast forms of the cities of the future, assumingly, of the XXI century, modernist or neo-modernist, but in any case consisting of glass and defying the laws of gravity, and form the core of the exhibition, its central hall number two. The hall is called “Imprint of the Future”, because the architectural views by Piranesi, which show us the city of the past, the antique and baroque one, literally have some sci-fi constructions imprinted into them – as if the author of these “collage etchings” is telling us that, although these constructions are not there yet, they are quite likely to appear at some point in time, making the buildings of the times of the Roman emperors clash with the modernist fantasies of our day and age within the space of the etching board. The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Arco di Settimio Severo”Copyright: The etching was made by Ioann Zelenin by Sergey Tchoban′s drawingIn addition to the “core hall”, the exhibition also has hall number one, which displays “pure” city views without any sci-fi insertions: modernist cities of the XX century, classic European towns, and Saint Petersburg, the home city of Sergey Tchoban. The principles of a traditional city are explained as we move along the exposition: it is a combination of centerpieces and background construction, arranged both vertically, in accordance with the “basement-middle-top” principle (the top always being lighter and more slender), the prevalence of the bearing wall (windows area under 40%), the material nature of the walls, and the décor. The same exposition explains that the city of the XX century breaks away from these principles: “the architects have an urge to design iconic “sculpture” buildings, whose sizes and shapes would be contrastive with the historical environment, this contrast radically changing the hitherto stable city fabric”. In , Sergey Tchoban commented on his attitude towards the “overprotective” town planning policy of today’s Saint Petersburg. The third and final hall displays a multitude of drawings that develop this theme, started in the “altered” Piranesi etchings, namely, that of coexisting constructions of different times within the space of one historical city, which get ahead of the modern technology-inspired fantasies. Some of the drawings precede the “Piranesi etchings” in terms of time of their creation; some are actually sketches, and some – one can see that – were drawn specifically for this exhibition. All the three halls come together to form a graphic statement, complemented by verbal explanatory notes, authored by Anna Martovitskaya, one of the curators of the exhibition. The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Veduta della Piazza della Rotonda”Copyright: © Sergey TchobanThe Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “The Trevi Fountain”Copyright: © Sergey TchobanThe compositions can be conditionally divided into the following groups: recognizable views of the historical city with skyscrapers in the background, fantasy views of historical architecture that grows in modern tiers – the higher it grows, the more “modern” and the more bolder it becomes, yet still staying within the overall logic of the historical city, described in the comments to the exhibition; “phases” of the city, where one architectural layer is replacing another, skyscrapers of “Chicago” type, and the glass “City”. It looks as though the author of all these drawings examines different types of interaction between the old and the new, tasting them and drawing comparative historical parallels.  The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Altra veduta del tempio della Sibilla in Tivoli”Copyright: © Sergey Tchoban The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching "Veduta del Tempio, detto della Tosse"Copyright: © Sergey Tchoban The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Veduta del Tempio di Ercole nella Citt di Cora”Copyright: © Sergey Tchoban The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Veduta del Porto di Ripetta”Copyright: © Sergey TchobanAt times, in addition to the associations with the downtown areas of different cities, a reminder appears about the already committed architectural invasions, such as the fact that near the Arch of Septimius Severus at the northwest end of the Roman Forum now “shoots up” a tower that looks line London’s “Cucumber” by Lord Norman Foster, which presents a textbook example of a contrast between the old and the new. The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Veduta di Campo Vaccino”Copyright: © Sergey TchobanAnd, finally, like the climax of this search – a city laced with glass tentacles. Detached from historical buildings, the broken lines and volumes gradually become “bolder”, take on curved and winding shapes, and repeatedly pass through the buildings. Particularly bright, or maybe, sarcastic, looks the drawing of the Coliseum. The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching "Veduta dell′Anfiteatro Flavio, detto il Colosseo"Copyright: © Sergey TchobanOn the whole, it is rather obvious that this theme of contrastive crossing, exaggerated difference and blatant opposition between the modern and historical architectures, or, even more, the old and the new city, which Sergey Tchoban has been interested in for years, has been taken to a whole new conceptual level in the Roman exhibition. First, the imprints of the “ruined” Piranesi etchings are in itself enough to present an experience akin to laboratory modeling. The futuristic buildings are not just placed in the context of this historical city in its more-than-200-year-old state (the Arch of Septimius Severus has not been dug out yet), but also the material of execution, characteristic for the XVIII century: copper etching. Had it been a render on a computer screen, where the panorama of today’s Rome had a couple of skyscrapers and cantilevers inscribed into it, this would have been just a case of Visual Landscape Analysis, only on a hypothetical topic. In this case, however, the objects are placed not into modern Rome, but in its older version, and, in addition, they are executed in Piranesi’s technique. “The Imprint of the Future'' puts one in the mind of a sci-fi novel or movie, where the characters find themselves in the past, and the consequences of their activity start showing in old photographs and newspapers, which are accessible in our days – these characters may have made a positive or a negative difference, but the important thing is that they did make it, and left a footprint. Here, by and large, we are also dealing with mystification, as if we are looking at evidence of a time machine. The difference is that the time machine hoax is disclosed in advance, and these pictures refer to time the same way that an icon – according to Uspensky – refers to space: in an icon, God is looking at us from beyond, and here the future is watching the past, trying to get reflected in in it, like it would in a mirror. Such “working with time” echoes the creative activity of Piranesi himself: he also studied the Ancient Rome, etching the floor plans of famous buildings that he recreated (and it must be said that in Piranesi’s engravings, the city sometimes looks more interesting than it does now – it has many buildings with petal plans, all lace-like). Piranesi recreated Ancient Rome, from candle sticks to planning structures, to giant vaulted spaces, that is, turned the present to the past, or broadcast the past into the present. Sergey Tchoban, on the other hand, is experimenting with the future, trying to forecast the vines that can grow from the seeds that we are now sowing. They cut through the ground and penetrate windows, hang with a luminous net over the ruins, and explore the spaces inside. The Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching “Veduta dell′Arco di Tito”Copyright: © Sergey TchobanThe Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching "Veduta della Basilica di S. Giovanni Laterano"Copyright: © Sergey TchobanThe Imprint of the Future. Architectural fantasy inspired by Piranesi etching "Rovine del Sisto, o sia della gran sala delle Terme Antoniniane"Copyright: © Sergey TchobanMost importantly, however, they watch. There is stuffage all over the place. In the XVIII century, this was common practice, just like it was in the architectural graphics of the XX century too: the drawing is accompanied by human figures that make it possible to understand the scale (not be confused with the practice of avoiding having people in architectural photographs). As a result, we see among the ruins pastoral peasants wearing hats and sitting down on the remains of the columns; sometimes these are people in cocked hats and frock coats giving orders to servants – a clear echo of the XVIII century. And above them, in glass tubes and cantilevers, equipped with elevators and escalators, move the modern-age observers, and they are even drawn in a slightly different way – like a modernist and not neo-classic stuffage; the human figures approach the “televisions” of the cantilevers, watching from inside of them. The result looks slightly like a museum, again, of a pretty sci-fi kind, some fairytale park – two different worlds that cross in space, remaining isolated from each other: the tourists are watching “the pictures of the past” – a narrative, which is also used in many books and movies. But then again, to be more exact, I must note that the “tourists” in glass volumes are to be seen all over the place, while the peasants appear, probably, as a consequence of development of the author’s views from drawing to drawing, or, even maybe as a consequence of his turning to Piranesi. Here appears yet another parallel from the field of lyrical science fiction. The historical city is watched not only by the people in glass tubes but also by the tubes and cantilevers themselves, their facial expressions being probably even more interesting than those of the people – the curious snail’s eyes, energetic, but generally rather friendly. As compared to Le Corbusier’s “radiant city” that replaced all preexisting structures with its repetitive houses, and to Iona Friedman’s “spatial city” that hovered above the old buildings on slender columns (preserving the old buildings, albeit in a slightly cool and aloof manner of “overhanging”) – this relationship between the city of the past and the city of the future is quite peculiar here. So much so that the latter does not even look like a city but rather like a museum locked in an airtight space. Meaning – these people may live someplace else, in some city like Plan Voisin, or maybe on the moon, only occasionally coming down here to watch this old city. One way or another, these glass intrusions, which first appeared in the drawings by Sergey Tchoban in the form of a background of dissonant towers, look as though they were “searching for connection”. Another thing that comes to mind is the Soviet cartoon movie “The Contact” (1978) directed by Vladimir Tarasov, with a screenplay by Alexander Kostinsky; in this cartoon, as we remember, an alien tried to establish a contact with an earthling artist, and everything eventually did work out. Peculiar is the fact that in this cartoon “attempts at contact” occur first through observation, photographing, and then through the reincarnation of the alien: he turns into a pair of boots, then into an easel, but the contact only occurs when he assumes the appearance of the artist. The graphics by Sergey Tchoban also looks as if it were making repeated attempts at contact, and one can see that the attempts of the new architecture to become like the old one appear only in one series of drawings, least numerous. Generally, on the other hand, the interaction is based rather on the aggressive contact, at the same time stopping short at the first stage of observation (and, possibly, photographing things). We will note here, that the artist (the “object” of the contact in the cartoon) also changes his attitude from being scared to being indifferent; here, in the etchings, the old city is mostly indifferent. But then again, on the other hand, one can easily imagine that this city is reacting to what’s going on with different degrees of ruins, which can indeed be interpreted as fright. One can hardly say that these observations give plenty of hope for a successful contact. The sheer fact that people in these spaces are fully isolated (by time, perhaps?) does not inspire any particular optimism. What is still more important, however, is, probably, the fact that the possibility of contact is not entirely ruled out, and even still more importantly, there is no “doomed sarcasm”, even though at times, one can indeed sense the smell of it. However, the exhibition is rather posing questions and searching for answers than is offering ready-made recipes. “… if we are to consider the European city to be a quite definite centuries-old system of interrelation between empty and build spaces, low-rise and high-rise elements of constructions, as well as their silhouettes and surfaces, then how are we to address it today? What conditions for peaceful coexistence of the old and the new are we to provide for it?” The explanatory notes also contain words to the effect that the calls to recreate a European city are hardly feasible nowadays. Furthermore, the drawings are beautiful – beautiful enough to give us reason to state (even if reserving a possibility of some “Itinerantly” critical component) that the “us and them” rhetoric, so characteristic of our contemporaries and countrymen, is not to be found here. Rather, this is a new statement on the subject. And, in my opinion, it is slightly different from the message contained in the “30:70” book. Some of the contrastive compositions exhibited here have already figured as illustrations to this book. The exhibition, on the one hand, yet again highlights the controversy described in it, but, on the other hand, demonstrates that the matter is even still more complex, bringing to light the conflict between modern and historical architectures. While the book had a recommendation: if you want to get a nice city, then in addition to neutral prefab houses and flashy landmarks, you also need to build something calm and neatly decorated, capable of arresting one’s gaze – the exhibition seems to state that such a compromise is just impossible. Modern architecture is simply incapable of following the logic of an old European city. Either this statement is polemical, calling on modern architecture to change its ways (which is hardly possible, judging from the explications). Or the recommendations gave way to posing questions, which is basically what art is all about, if we are to consider it to be one of the methods of analyzing reality. |

|